There are coincidences and there are coincidences. According to the dictionary, the word describes a remarkable concurrence of events or circumstances without apparent causal connection.

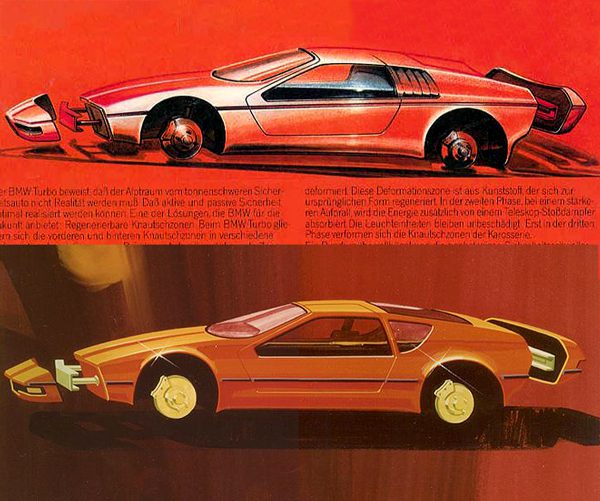

At top is an illustration from the brochure of the BMW Turbo. Beneath, an illustration from a document outlining the DeLorean Safety Vehicle. This is no coincidence.

It’s early 1974 and John DeLorean already had a lot to look back on.

Not ten years before, he was the youngest-ever head of a General Motors car division. Don’t let those baby-jowls fool you; this guy was a tiger.

By education, an engineer and MBA. After a short stint with Chrysler, John DeLorean got a job at Packard and by 1956 was head of Research and Development. It was a soft start to an automotive career; Packard was seriously on the wane but nevertheless a lesson in itself. It was here that John DeLorean became closely acquainted with the Mercedes-Benz 300SL Gullwing.

Working on a fuel-injection project, he had turned to one of his engineers, Heinz Pringham, for advice on the best system available. Heinz opined with the Bosch unit used on the Gullwing. DeLorean instructed him to buy one of the cars for appraisal. For six months it was Pringham’s daily driver; enjoyed especially by his son Frank (at right) on school runs.

September of 1956, and DeLorean was in charge of advanced planning at Pontiac. He reported to new chief engineer Pete Estes under recently-new division head Bunkie Knudsen. The right place at the right time. Knudsen initiated a 20 year golden run for a moribund Pontiac, and DeLorean was a key figure in its success. An early inadvertent effort would resonate through the next decade.

In 1957, I was working with Chuck Jordan of GM Styling on developing a new independent rear suspension system for an advanced model car. We ran into a problem mounting the suspension system on convertible models, which were the rage of the era. To do the job, we had to spread out the rear wheels. And to make the car look right, we had to do the same to the front wheels. This gave our big cars a 64-inch tread.

We put the car into clay mock-up form and the two of us were amazed how the car looked so much better planted on the road. Widening the tread gave the illusion of lowering the car. The instant Bunkie saw the car he said, “Let’s put that on a production car”.

Very early spring 1963 and chewing the fat with Bill Collins and Russ Gee at the Milford proving grounds. Bill pointed out the 389 V8 engine would fit into the new Tempest. Russ proposed building it in his Experimental Department. DeLorean gave the go-ahead.

By now Pete Estes had taken over Bunkie Kundsen’s job, and DeLorean was chief engineer. Problem was, GM rules didn’t allow for such a large engine in an intermediate model. So Estes put the engine into the range as an option and not as a model, a canny move to avoid scrutiny by the Fourteenth Floor. The dawn of the muscle-car.

In 1965, a 40 year-old DeLorean was appointed head of Pontiac. He inherited it a marque in ship-shape. The range was still setting benchmarks across the entire industry, let alone within the General Motors family.

His remit was now much broader, and he found himself having to deal with issues such as outdated plants and a recalcitrant sales division as much as the product itself.

He was no longer reporting to just one man; from now on he would have to justify himself to the Fourteenth Floor.

This suite of executives built on a Sloanian framework was positioned at the top of the whole GM hierarchy. Chairman, Presidents, preferred Vice-Presidents and the all-powerful Committees worked, ate and sometimes slept in an exclusive zone covering one of the end I-sections of the GM building in Detroit.

These were supra-divisional beings sitting at the apex of corporate America. And yet in 1965, this 1920s structure was calcifying.

DeLorean didn’t stop moving. He was already working on a sporty two-seater coded XP-833. It was to be smaller than the Corvette with as much sourced from the parts bin as possible. The idea was to provide a very wide range of options over a relatively cheap base. DeLorean was quite partial to this project; Bill Collins had put the idea to him in 1963 and they kept at it. By 1965, two running protoypes were built; the first powered by a 230 six, and the second with a 326 V8.

In September 1965, Bill Mitchell received a memo instructing him to repurpose the Pontiac XP-833 clay into ‘a Chevrolet design for the two-passenger version coupe.’

Maybe this one.

Top image is the Corvair Monza studio around 1962. Beneath, Shinoda and Schinella’s XP-819 ‘Ugly Duckling’ – a rear-engined Corvette prototype from 1964.

This language was not Pontiac’s property. It belonged to General Motors.

And General Motors could do whatever they damn well like with it.

But this was all still beyond John DeLorean’s pay grade; Fourteenth Floor stuff.

He pleaded through to March 1966 for the XP-833. As a consolation of sorts, he was allowed to turn the Camaro into a Firebird.

His fixation with reducing size and weight continued. In 1967, he arranged for some models to be built of a proposed new fullsize range for Pontiac. They were based on the intermediates, but using a longer wheelbase. These models were so impressive, DeLorean managed to convince Pete Estes – now running Chevrolet – to go along with the project. Again: no from the Fourteenth Floor.

Except for one; the (wildly profitable) 1969 Grand Prix.

In 1969, DeLorean was running Chevrolet. The fast lane. Instead of one assembly plant, he was now juggling eleven.

It was a corporate car, not a divisional car.

It was being put together by people at least one step removed from the marketplace.

His time there is typified by the Vega. Although he was an exponent of a smaller car, the Vega was a child of the Fourteenth Floor. It was overseen personally by President Ed Cole and shaped by Bill Mitchell. Since the early 1960s Pontiac and Chevrolet had been developing their own sub-compacts, but the corporate proposal was chosen. This car put to market was well under par as both a sub-compact competitor and a consumer product.

DeLorean was subject to massive gravitational forces; where the inexorable rise is the compelling force without regard to necessity. He was hardly able to attend to Chevrolet’s many issues before being pushed upward into the Fourteenth Floor in 1972. The realm of learned helplessness. No longer tied to the day-to-day of running a carmaker, DeLorean was set adrift in ineffective meeting after meeting.

He was also suffering a personal withdrawal of sorts. Through Chevrolet’s marketing efforts in Hollywood, he had become one of the westcoast jetset. At the company’s expense, he enjoyed a sybaritic coterie far apart from the stuffed shirts and country clubs of Detroit. Access to this lifestyle was quelled somewhat by his separation from Chevrolet, and no doubt fed his frustrations. He wore a suit, but it was too flamboyantly cut. And he let his hair grow.

The Fourteenth Floor didn’t want him there, and he didn’t want to be there. Whether it was he or someone else who leaked the Greenbriar speech (his Jerry Maguire moment), his time this close to the sun was over.

DeLorean agreed to leave GM in June 1973. Not that he seemed to have much choice.

And now John was hanging loose.

There was no longer a $650,000 income, but there was the GM soft landing. DeLorean spent a year as a President of the National Alliance of Businessmen working on a project around employment for the disadvantaged. He gave speeches promoting his ideas on car size and weight savings.

At one outing he revealed that he had designed two cars over the past year; a mini-commuter and a sporty two-seater.

In early 1974, he met with journalist J. Patrick Wright and a book deal was made with Playboy Press. For the next year Wright took notes from conversations with DeLorean, then wrote out a text in first-person-John outlining the industry’s failures and his success. It included such chapters as How Moral Men Make Immoral Decisions that touched on GM’s handling of the Corvair.

Shown a finished manuscript in 1975, DeLorean was impressed but he was wary of GM and backflipped on publication. Despite this, he also refused to return Playboy’s advance and the project was left in limbo for four years.

In 1979 Wright published the book himself at a cost of $50,000, and saw nearly a million dollars from its sales.

DeLorean’s term with the National Alliance of Businessmen earned him his GM base of $200,000. There was a scattering of other interests including property – though none delivering at the scale of his previous employer.

He had a share in Grand Prix of America, seen above with second wife Cristine at the wheel. This was a Bricklin-inspired venture with the general public paying to drive rotary powered reduced-scale racers on private tracks. It was a dud and that year fell into bankruptcy. DeLorean ended up being sued by his brother Jack, who had brought him the deal.

In January 1974, he formed the John Z. DeLorean Corporation.

He was captured that June in his Detroit office by Time/Life. The putative car was now definitely a sportscar; save for the bike renderings there appears to be nothing of the mini-commuter. On the wall next to him are a number of car diagrams; Fiat X1-9, Porsche 914 and two mid-engined Corvettes.

When John became head of Chevrolet, Zora Arkus-Duntov introduced him to the Corvette concept they were planning to show that year.

If Harley Earl was the father of the Corvette, Arkus-Duntov was its cool uncle. He had been called in just after the car was conceived to add some zep to its performance. His became the dominant will on the model; he notoriously clashed with the Bill Mitchell on the C2’s split window. Mitchell won the battle, Arkus-Duntov won the war.

Nearing retirement, the XP-882 was to be Zora’s swansong.

The XP-882 project was commenced in 1967. A Toronado transfer case was mated to a 454 and positioned behind the driver. The body was slightly cab-forward and had a wide grille aperture that looked unfinished. This might have been as a result of airflow for the distant engine. The clay shows the shape with a more enclosed mouth, sharing the contours from the rest of this attractive shape.

Two cars were built, one for the 1969 New York Auto Show. It didn’t make as much of a stir as expected and the project was parked.

In 1973, DeLorean asked Bill Mitchell to provide a revised version of the XP-882. It was called XP-895 and involved an overhaul of the body. A sugar-scoop theme was used at the rear and the nose was slightly more faired with NACA dusts added. One of the 1969 cars was the donor for XP-895, with a body built in steel. It was too heavy.

DeLorean had an exact replica of the platform and body made in aluminium by Reynolds Metals. It was too expensive.

The other 1969 car was to become one of the greatest shapes to emerge from General Motors.

Thanks to a longer nose and revised greenhouse, this was the XP-882 as it should have been. Still cab-forward, the centre line defined by the leading point of the nose and the crease of the windscreen succeed in balancing the equilibrium. It is dynamic but not overbearing, with clean curvature and surfacing delicately but assuredly tempering the razor’s edge. Very sophisticated, but wondrously simple.

It was the work of Hank Haga and Jerry Palmer, with Ted Schroeder, Randy Wittine and Ron Will playing their part.

This shape very nearly made it to production. In 1975, it received a fresh round of promotion as the aero-vette. The aluminium chassis from the Reynolds XP-895 with 400 V8 was used as the basis for a road-going car and as of 1976 it was approved, with orders for production tooling awaiting go-ahead.

But Zora was gone. He retired from General Motors in 1974, and his cherished mid-engined Corvette had lost its greatest champion. The orders were never greenlit.

The aero-vette shape was first seen in 1973. Back then they called it the 4-rotor and it was a priority for GM.

Very, very reluctantly, Arkus-Duntov had put a rotary in the Corvette. In 1972, a 585 cu inch 4-Rotor was mated to the first 1969 XP-882 platform and Arkus-Duntov took President Ed Cole screaming around the 1-mile track in the bodiless car. It was still pulling when they backed off at 148 mph.

The 4-Rotor got a significantly better body than the concurrent XP-895.

The 2-Rotor got the XP-895’s sugar-scoops with the 4-Rotor’s windscreen crease. Ordered in 1973, XP-897 was a rush job and had to be built by Pininfarina. A Porsche 914 was sent to Italy and received a new body to a GM design over a 180hp rotary.

Tha 4-Rotor and 2-Rotor were sent to Paris for exhibition in October 1973. By the time they got there, GM’s rotary program had effectively been cancelled.

DeLorean was telling the press he had tried to get the mid-engined Corvette. What he was really angling for was the little Porsche-based XP-897.

He did end up getting a Fiat X1-9 – the Red Rocket. A DeLorean feasibility mule with Ford Cologne V6 mid-engined power married to a cartoon rear.

But that was still a year away.

The Red Rocket was to be prepared by Bill Collins, DeLorean’s colleague from the Pontiac days. In 1974 Collins had just completed overseeing the development of the downsized B-body platform for General Motors and was mulling more money at American Motors.

John got in touch about working on a sportscar. With gullwings.

They had worked with gullwings before.

The 1963 XP-798 project was a pre-emptive move against the Mustang. The longnose body housed a 421 V8 almost mid-front and was independently-sprung all round. It could have been a very nice driver.

It was a gorgeous shape. Except for those 20 inch doors and pathetic winglets.

The XP-798 was slated for the New York Auto Show in 1966 and given the name Banshee. At the last minute it was dropped from the show, and the first Pontiac Banshee was never actually seen by the public.

When DeLorean came calling, Bill Collins was driving around Detroit in his little Pontiac roadster.

In preparing to leave General Motors, he got to thinking about the XP-833. Back then, Collins and colleague Bill Killen had somehow managed to have the two functioning prototypes hidden away on site. If he was ever going to get his hands on it, now was the time.

Miraculously, Pontiac agreed to sell. Killen got the silver one. Collins got the V8.

The XP-833 was never a Banshee until 1973, when Bill Collins went to the design staff, retrieved some badges from the still-unseen XP-798 project and put them on both his and Killen’s roadsters.

Bill took the sportscar job for less money.

When he arrived in late 1974, he was greeted by the model on John’s table. Not likely a General Motors artifact, it was probably crafted for John by some Detroit professional in their off-hours. It’s a smart shape, though taking a lot from the Maserati Bora.

Giorgetto Giugiaro’s Maserati Bora.

But that was so 1971. By now, Giugiaro was folding paper.

As soon as he joined, Collins was on the plane to Italy with DeLorean. At the Turin Salon were two new shapes from Italdesign; the Hyundai Pony Coupe and Maserati Coupe 2+2 concepts rendered in Giugiaro origami. The three men got to talking.

John and Bill returned to the US, having decided on Giorgetto, but not having commissioned any work.

On his return, Allstate Insurance got in touch with John. They had been impressed with his talks on safety and standards during his recent public tenure. DeLorean was asked to prepare some papers around automotive safety, with a particular focus on the airbag. His work outlined savings that could be made, not only in lives but in dollars too, and Allstate was impressed.

They offered him $50,000 to develop the idea of a safety car that could be built in 1975.

DeLorean prepared a brochure.

Significantly, there is no mention of Allstate throughout the piece.

The arrangement DeLorean was seeking was one where he kept all the car’s intellectual property for himself. What Allstate was buying was the right to associate themselves with the product. Implied by their absence within the text; if Allstate passed on this document, it could then be presented to another party – another insurance company perhaps.

One thing’s for certain, this document was not for public consumption.

Not all the intellectual property was DeLorean’s.

In August 1972, the BMW Turbo was presented just before the Munich Olympics. Though an attractive car, it was soon overshadowed by the hostage crisis that unfolded that September.

What’s even less-remembered is that the BMW Turbo was a showcase in safety.

The concept itself had been rushed to fruition. With only six months to the Olympics, Paul Bracq and Bob Lutz were still to convince CEO Eberhard von Kuenheim to produce the company’s first concept showcar. It was finally approved, but it was to also feature safety. With a name like BMW Turbo, you’d hardly know.

It had a progressive crumple zone that was never actually tested and radar systems regulating the car’s speed that were never actually demonstrated. The principles were correct, but the BMW Turbo was more a compendium of possibilities.

All there was to show for its safety aspirations was a 4-page, 8-sided foldout brochure printed in English and German that was given away at European motorshows that year.

Paul Bracq himself illustrated the brochure. His distinctive style popped out of the saturated orange.

Whoever did the work for DeLorean, they were a professional.

The similarity doesn’t stop with the images. Both texts start with a negative appraisal of the way contemporaneous safety cars appear. Both point to the high-sill of the gullwing doors being a safety benefit. And so on.

The specifications and dimensions were different; the DSV being a larger car.

The gamble paid off. None of the senior actuarial-types at Allstate remembered the BMW Turbo, if they’d ever seen it in the first place.

DeLorean got the $50,000.

Giugiaro would have spotted the similarity in an instant. I doubt he was shown the whole document.

He received the specifications and dimensions in March 1975. I don’t know what he was to be paid, but there was a $65,000 bonus due when the cars entered production.

In 1968, James Hanson convinced Pininfarina to build him a bespoke car. It was a coupe shape on a Bentley T-series platform, and Hansen was hoping to sell the idea back to Rolls-Royce as a Bentley Continental. Pininfarina provided a fully functioning car ‘at cost’ for £14,000.

Giugiaro was only to supply a wooden mockup, so I would estimate his ‘at cost’ price on delivery to be about $30,000.

None of the early proposals look like the BMW Turbo. On the whole they are much closer to Giugiaro’s Hyundai concept than any other car.

With an option chosen, Bill Collins insisted on dealing with the rear pillars for visibility. A louvred appraoch was considered, but a clean glass aperture was the better solution.

When it first saw daylight, the wooden mockup looked wonderful from any angle.

How gratifying it must have been to lean against this most handsome and tangible thing.

The wooden exterior mockup and a capsule housing the interior mockup were handed over to Bill Collins by Giugiaro in June 1975. Collins asked for the technical drawings defining all of the surfaces.

A surprised Giugiaro replied; ‘I’m sorry Mr Collins, but it is the model that represents our definitive work, not any drawings. You’ll find that specified in the contract.’

Allstate was so pleased with the mockup, in late 1975 they gave DeLorean $500,000 for the construction of three functioning prototypes.

Curiously, when the DSV was first revealed that December in Road & Track, Allstate’s name was nowhere to in the article.

Allstate did get mentioned the next time. Quite a lot in fact.

That was February 1976, in Popular Science. After that they were never heard of again.

In October 1975, the DeLorean Motor Company was incorporated.

Transferred to the new entity was all the car’s intellectual property from the John Z. DeLorean Corporation at a nominal value of $3.5 million.

That nominal value was provided by Zora Arkus-Duntov.

The first of the functioning prototypes was still a year away. At this exact point in time, the only real assets they had were the wooden DSV exterior and interior mockups, and the newly-arrived Fiat X1-9 feasibility mule. Probably less than $100,000 in capital expenditure. Even if you sift Arkus-Duntov’s dollar figures through the layers of GM bureaucracy, there is still a large disparity left over.

The value of intellectual property.

In the end, over $150 million in investment and tax incentives would evaporate. Charges would be laid, but a heavily beaten John Z. Delorean emerged legally unscathed.

For further reading on this, I recommend Dream Maker, The Rise and Fall of John Z. DeLorean (UK title: DeLorean…). Two financial journalists, Ian Fallon and James Srodes, were on the trail before the drug scandal hit and map out a dense trail on both sides of the Atlantic. It’s a compelling, dispiriting read. We see greats such as DeLorean and Colin Chapman of Lotus for their financial feet of clay – to put it politely.

We meet Roy Nesseth, above, a car dealer with convictions for fraud; he was to DeLorean what Harry Bennett was to Henry Ford. The conduct described is negligent at best and criminal at worst. Published only three years after On a Clear Day, this book makes for a sobering counterpoint.

The car changed.

A lot. From a body in ERM, to fibreglass to bare stainless steel. Engines from rotary to Citroen 2 litre to Ford Cologne V6 to Douvrin V6. A backbone chassis became necessary, leading to the decision to move the engine from mid to rear. From this carguy’s perspective, at that last point the vehicle became unacceptably compromised.

For an overview of the car’s development, I recommend Aaron Severson’s excellent piece at Ate Up With Motor.

The shape hardly changed.

At top, the original DSV wood mockup. Middle right, the first functioning prototype delivered in 1976. which follows the shape of the wooden mockup closely. In front of it, a pre-production prototype. Most of the change was in the driver window frame. At bottom, the 1981 DMC production model showing minor alterations to the nose. Nothing of the shape has been compromised, not even moving the engine.

The only thing that disappoints is the brushed metal finish, which doesn’t photograph as well as the painted wood.

Comparisons with the Esprit are inevitable. Its mid-engined dynamic hints at what the DMC could have been.

But this Giugiaro shape was designed around Colin Chapman’s chin-to-chest racing posture, and the DeLorean was a taller proposition, a gentleman’s express. That grille serves in some ways as a metaphorical necktie.

In a genuine coincidence, Giugiaro was asked to shape the BMW M1. Which he did, with a side treatment he had tried on the DeLorean.

The DMC was superior. One of Giugiaro’s better efforts for the time, but no iconic shape like the 300SL.

It achieved its icon status thanks to kitchen appliances.

When Bob Gale and Rob Zemeckis were writing the script for Back to the Future, the time machine was originally a fridge. Then they realised the possibility of children mimicking the movie, so they found something better. Only 4 years before, John DeLorean had gone down in flames after being arrested on drug trafficking charges. For the western world, it was the Edsel saga as seen on Miami Vice. The irony was well-milked for laughs. This classic piece of cinema still hasn’t aged.

Personally though, I prefer the shape without a Magimix sitting behind the cabin.

Until a few weeks ago, Paul Bracq was unaware of this document. I sent him a copy and he was not impressed with what he saw. Nevertheless, he was complimentary about DeLorean during his Pontiac years.

I don’t believe BMW were aware of it either, let alone their permission sought. I do believe it’s genuine, so to speak.

It was retreived from a website run by Tamir Ardon. The site is a deep repository of press clippings and documents relating to DeLorean, which gives me much faith in its provenance. Moreover, Tamir assisted Aaron on his AUWM piece.

It also matches a description given in the Fallon and Srodes book of a document as found in the Allstate archive. I’m fascinated to know how Ardon came across it.

Late 1975, and Bill Collins is demonstrating ERM to the interviewer. In front of him; a 1:12 scale-model of the BMW Turbo with the passsenger compartment removed. Those slightly oversized wheels give away its origins.

Bought off the shelf.

I want this guy to win.

He dresses like Laurel Canyon aristocracy, and has a gorgeous wife to wrap his arms around. For his Pontiac years alone he is an Immortal. And this car looks so full of promise.

His best years came in a cocoon. He flourished within the massive infrastructure of GM; coddled by the very system he rebelled against. Without that deep deep-pile cushioning, he had no way to absorb the many bumps on the carmaking path. He didn’t set out to crash, it just accelerated that way.

And yet you have to wonder what sort of man finds himself in a hotel room negotiating millions of dollars for kilos of cocaine; entrapment or otherwise.

In 1948, a 23 year-old John DeLorean was questioned by the FBI. It seems he had taken a Yellow Pages telephone directory, clipped out the ads and sent them to the advertisers with an invoice for the next year’s payment. These payments were to be made to a company registered under a name similar to Yellow Pages, but owned by DeLorean. Thanks in part to character testimony from his college professors, charges were never pressed.

…

My appreciation to Mr. Paul Bracq

DSV brochure and Prospectus page at Tamir Ardon’s site

Zora Arkus-Duntov letter at deloreanmuseum.org

EfficientDynamics and the BMW Turbo

…

I remember the Delorean from the 80s Back to the Future movies I still watch them time to time !

What a fantastic write up, Don !

Truly one of the most compelling biographies in automotive history.

(somewhere in the cellar there´s still my remote controlled BMW M1 by Gama, which I received for xmas 1982, collecting dust)

We (my brother and me) had a white version of the BMW Turbo. IIRC is had chromed wheel so I don’t think it was the Schuco one, but I haven’t been able to find another like it online.

you mean this one?

The one we had felt a bit smaller. It had the same twin globes in the popups, so I’m wondering whether it was a later repackaging of the Schuco.

1972 was a high point for BMW / Bavaria / Munich

The Turbo

The first 5 Series

and the Olympic Games

plus this building

there was seemingly one with and one without a cord

do it yourself

Schuco seemed to have quite a few including diecast. Our was definitely white, but I’m starting to think it was a Schuco 1:12 plastic electric car without cord.

oh yes…the BMW “Vierzylinder” building.

It was completely remodelled back in 2006.

This is what it´s interior looked like when new….(the typewriters !!! 😉

another view

http://www.bmwmagazine.com/de/de/node/1872

Enjoyable read Don. I’m the guy with the Delorean from Fed square the other week. Always good to get additional insight.

All the best.

Hi Tim. Nice car, and an absolute pleasure to see on the road.

Wow, Don – some fascinating stuff here. It is interesting to consider how you would have become an internationally known investigative journalist – if only you had pulled all this together around 1981. Instead you will have to content yourself with the admiration of those of us into automotive history.

You make me wonder who was the last high GM executive who went on to *successfully* run a much smaller company, automotive or otherwise. I can think of Charles Nash and Walter Chrysler, but those examples go back something like a hundred years. I am sure there are others, but they are not coming to mind.

I think that the skill set to operate within a big systems-driven organization like GM is far different than the one needed to navigate a much smaller and less powerful business.

Is the text of the Greenbriar speech online anywhere?

Don’t think so. It was leaked to Robert Irwin of Automotive News, and he wrote it up in detail with quotes March 17 1973, the day before the GM conference commenced.

“In 1948, a 23 year-old John DeLorean was questioned by the FBI. It seems he had taken a Yellow Pages telephone directory, clipped out the ads and sent them to the advertisers with an invoice for the next year’s payment. These payments were to be made to a company registered under a name similar to Yellow Pages, but owned by DeLorean. Thanks in part to character testimony from his college professors, charges were never pressed.”

Such an interesting and poignant paragraph, that one.

This was an amazing read, and the closing paragraph brought it all home so succinctly. The inclusion of this seemingly remote statement of fact seems to answer most, if not all, of the unanswered questions about how, why, and why not. It’s brilliant.

Thanks MTN. I originally put that paragraph at the start of the piece, but it so coloured the reading of the text I left it to the end.

Which was the right call. A brilliant ending.

This anecdote from 1948 is startling. Where does one find substantiation for the statements here? Did the FBI keep records that are now public? Is there common first-hand accounts of these events taking place? Did DeLorean actually write about this himself? I cannot find any mention of this in a quick search of the web.

On the whole, a solid, enlightening piece.

The story comes from the Fallon & Srodes book. There was a photograph of JZD leaving the FBI building with accompanying story in the Detroit Times Nov 13 1948, but that paper is long gone. Apparently the records have been destroyed, but given this anecdote was published in 1982, JZD had another 20-odd years to sue if it wasn’t true.

A most impressive article, incredibly well written! That’s some top notch work…

But I’m more impressed you’re in mail conversations with Paul Bracq! He’s always been a favourite, that’s like being in a conversation with God. I hope you sent him the articles you wrote about him, I regard them as some of the best work ever written about him, and there really isn’t much out there. Most of all I’m curious what he thought about them, do you have any news on his reaction?

On DeLorean, I”ve always thought of him as your typical top level executive sociopath. Charming and seductive but a sociopath nonetheless and always getting much done just because of that. And always taking credit for other peoples work if not stealing them outright. I’ve always seen him as a fraud and con man, he seems to be totally amoral and exceptionally good in scamming people. But there’s always been a streak of street hustler over him, like ge could never shake the reputation of conning money out of people in three card Monte. He’s never been that far removed from the street, no matter how well dressed and glib.

I would say that your characterization of DeLorean is more or less correct.

And I bet that he derived massive pleasure from being like that – ´til he got got caught and his house of cards disintegrated.

Towards the end of his life he was trying to sell wrist watches.

Yeah, Delorean seems a lot like Malcolm Bricklin, only with a solid engineering background which got him into the insular GM world where he was able to flourish. In the sixties, he was the right guy at the right time.

Even with that, the story goes that he would have been fired by GM for the GTO subterfuge to by-pass GM rules to get it into production. It would have happened, too, if it had bombed. But the GTO turned out to be this huge hit, so just the opposite happened and Delorean not only kept his job, but got on the fast-track to the top.

Thanks Ingvar. Mr. Bracq does not do the internet, so my initial emails bounced back and forth in single-line stabs at cross-purposes. I sent him a copy of my piece on him, as well as this brochure. He gave me his phone number and we had a 40 minute conversation. Not interview. Just free flowing, every second sentence from Mr. Bracq was punctuated by a laugh or chuckle. He sounds hale and hearty.

A few nuggets:

He has never owned one of his Mercedes-Benz cars (‘Ha! The butcher’s car; a diesel. I like to drive fast.’). He bought his first 356 second hand in 1957, and his second 356 in 1961. After that I think he got a 911 during the 70s, as well as an E12 while at BMW.

He used to enjoy very much the autobahn between Stuttgart and Sindelfingen, although his employers would be slightly exasperated by his chosen brand.

He still has the 1986 205 GTi, but running on its second engine.

No single favourite car – too many to choose from.

He talked for a while about the importance of the full-scale model when styling, particularly before the WW2 when the shapes were much more convoluted aggregations rather than clean envelopes.

It was a very pleasant conversation, and he expressed his pleasure at my piece on him.

awesome – thanks for sharing.

His BMW E24 Design is one of my all time favorites.

“He used to enjoy very much the autobahn between Stuttgart and Sindelfingen”

That’s only short track!

KJ

I never new how the DeLorean come to be made thanks for the back story.

Quite a read. Nicely done!

A really great article! One thing I wonder about – did John Z have some eyebrow work done along the way? Inquiring minds want to know!

It’s not just the eyebrows. Rarely have I seen someone’s face change so much in a decade, especially in the prime of their life. If someone showed me that picture on the left and I hadn’t seen it before, I really don’t think I’d identify it as being JZD. It looks like he had chin augmentation surgery, which is actually a thing now.

His daughter went on a completely unhinged rant to the media some years back and she specifically pointed out he had a chin augmentation (and brought it up supposedly to show bias; you know, how dare photos pre-surgery exist).

That explains it. I should have known. He wouldn’t have gotten nearly as far with the LA glitterati looking like he did originally.

DeLorean’s own story was that he had a bit of work done only because he had a bone chip in his jaw from some prior dental work gone awry, but he did admit it at least that far.

That’s highly credible, like everything else from him.

Well, my point is that he didn’t even deny having work done, he just made minimizing excuses. Which was indeed very much in character.

Lol, “glitterati”, brilliant!

That’s funny. With the exception of auto enthusiasts (like those who read CC), the only reason anyone else would even recognize the name ‘Delorean’ is because of the Back to the Future movies. Even then, I doubt the vast majority of people have a clue that ‘Delorean’ was someone’s actual name. To most, they only know it as the name of a movie car.

Hell, I doubt if any non-gearheads under the age of thirty know who Lee Iacocca is.

Something, to me, has always seemed a bit visually off about DeLorean, and I had no idea that he had facial surgery, but it makes sense. The extravagant suits, the beautiful wives……there’s something about his facade that he wanted people to believe, but I don’t think that he was who he was presenting himself as. I totally agree that he fit the bill between conman and legit car guy……he had the smarts and the passion for cars, but he does seem at times like a low rent car salesman trying to sell you the nicest looking car in the lot, even if the engine is gonna fall out.

DeLorean told Patrick Wright that in his younger days, he was shy and introverted, so when he first went into sales, he learned some tricks to get over his shyness. Even years later, people sometimes remarked that there was something plastic about his charm, and a distinct sense of it being turned on or off.

This was the best thing I’ve read in a too long a time. Bravo, Don! You fell down a rabbit hole and you kept pushing yourself further down. And the result is absolutely brilliant.

Once again, I’m honored and humbled to have this here at CC.

Honoured to be here Paul. Thank you.

Paul is absolutely right! This was a tour de force and I thoroughly enjoyed reading every word!

I’ll second that. Diligently investigated, context credible and in order, brilliantly told. I think the word may be “definitive”.

Now, I must post my DMC-12 CC outtake shots.

What a read. And that closing paragraph provides much unspoken context.

One of DeLorean’s lines from the 1970 MT writeup about the Vega was that the brakes could stop a 2 1/2 ton truck. Anyone who ever drove the heavier Monza derivative could tell you what a line of BS that turned out to be.

By the way, the issue’s headline “1975 Vega” was TOTALLY perfect, an unspoken nod to the days yet-to-come when the annual model change wouldn’t be the thing it had been to that point…it also left a 13-year-old me with the impression that this car was SO cool that it could go FIVE WHOLE YEARS before needing an update!

Turned out five years later I was driving a ’72 Vega Kammback in black; a ball to drive with its GT engine and 4-speed, but so flawed in virtually every other way.

Let’s face it, the “Back To The Future” franchise did much to redeem DeLorean’s reputation after all the cocaine and fraud allegations surrounding him in the 80s and beyond.

He saw royalties off the movie, but I didn’t look too closely into how much he actually got.

A really great CC. Of course, I’ve also read both cited books, too. The rise and fall of Delorean is a fascinating read. I didn’t know about the BMW Turbo connection, but it makes perfect sense, especially in light of Delorean’s other immoral actions which came to light later. A couple of things:

– In a great case of “what might have been”, imagine if Packard had survived and Delorean had remained with the company.

– Delorean was a tall guy but, man, that photograph of Delorean in front of the ’67 Firebird convertible makes him look like Godzilla. It’s so bizarre it almost seems photoshopped.

– Delorean’s exit from General Motors seemed to be connected with some sort of shady deal involving selling modified Cadillac limos. Whatever it was, Delorean was quite hated at GM and they reveled in his departing under questionable circumstance. Supposedly, before he was killed in a plane crash, Ed Cole is reportedly have said that Delorean didn’t quit, he was fired.

– The Malibu Grand Prix places were actually pretty cool, giving a much better experience than the typical bottom-feeder go-kart track. The cars were rather fast and the rollbar and required helmet weren’t for show. But it’s easy to see why the places failed; upkeep on those cars must have been quite pricey.

– Association with Roy Nesseth. That guy goes a very long way to seeing into Delorean’s personality. In car sales parlance, Delorean would be the charismatic ‘opening’ salesman who, once the customer had committed, would hand-off to the hardline ‘closer’: Roy Nesseth. Behind all of DMC’s shadiest deals and actions was Nesseth. In the book, during DMC’s peak, it was written that Nesseth would book several airline flights at the same time, but going in four different directions as he wouldn’t know where he was headed until the last moment. Nesseth was also behind a late night attempt to steal one of the last shipments of Deloreans that were being held at the US port due to lack of payment.

– Delorean most certainly did not exit DMC unscathed. Although he avoided jail time, the lawsuits continued for decades (Lotus’ Colin Chapman comes off as a guy every bit as sleazy as Delorean), eventually obliterating his entire accumulated wealth and leaving him in some serious debt. In the end, I read somewhere that he was living off pure charity at the guest house on the estate of some wealthy friend who took pity on him. He did make occasional appearances at GTO events. Except for the jail time, Delorean’s demise comes off very much like O.J. Simpson.

– Although his last business venture (scam?), Delorean Time wrist-watches, failed to get enough suckers to invest, the webpage actually stayed up for years after his death. What a sad epitaph.

Thanks rudiger. Yep, that unscathed line was a bit of an understatement but I didn’t want to get into the details so I just left it at that. The bit about relying on the goodwill of wealthy others at the end of his life. Sad but apt.

There were a couple other interesting tidbits I recall about Delorean from the books:

– Delorean’s tight relationship with Pontiac adman Jim Wangers. Wangers really had his ear to the ground and his information was invaluable to how Delorean was able to provide the kind of Pontiacs that the youth market would lap up. Delorean might have gotten the GTO into production, but it was Wangers who exploited it to maximum effect. Delorean would never go street racing but, Wangers, OTOH, was a frequent passenger in Pontiacs (and later, Oldsmobiles) in the hottest GM factory musclecars on Detroit’s Woodward Avenue in the musclecar’s sixties heyday.

– Besides the limo thing, Delorean had some sort of side deal with a vendor to distribute an early videotape cartridge viewer to Chevrolet dealerships to help sell cars to customers. I vividly recall seeing one of the leftover machines in a waiting area at a small town Chevy dealership in the late seventies. Whatever the arrangement, it was something that didn’t go over well with GM upper management and likely contributed to his acrimonious departure.

– A major investor who actually kept DMC going at one point was a guy named John C. Carson, aka Johnny Carson. Carson, like so many others, was smitten by Delorean’s charm and charisma and had him on The Tonight Show as a guest at least once (and probably more). For a brief period, Carson would drive a Delorean DMC-12 between Burbank studios and his home. Of course, after Delorean’s arrest and Carson lost his sizable investment, Delorean was persona-non-grata on the show.

You’re right about Jim Wangers, but it just didn’t fit to go into detail.

The other interesting part I didn’t look into is that for a while around the time all this was happening, DeLorean was receiving $25,000 a month retainer from Peter Grace Jr. of the W. R. Grace & Co. conglomerate to work half his time on a fuel efficient motor home. In the 1980s after Bill Collins left DMC, he created the Vixen. Don’t know if this carried anything from the Grace work though.

I keep forgetting that Collins did the Vixen. It has his fingerprints all over it.

I’ve owned the J. Patrick Wright book On a Clear Day You Can See General Motors for many years and find it very informative. But it cannot be exactly the same manuscript that was completed in 1975; presumably it was Wright who (as “De Lorean”) mentions, for example, that the Vega was discontinued after the 1977 model year.

hehehe. channeling

The book didn’t come out until 1979. Wright obviously updated it to reflect changes like that which had happened since DeLorean gave him the story in 1974.

Excellent article! I remember David E. Davis Jr.’s less than flattering tribute to John Z. De Lorean when he died – that man was the epitome of slick based on what I read here! Interesting too that the features of the “safety vehicle” are pretty much commonplace on cars at all levels today.

The David E. Davis Delorean ‘tribute’ sounds like it’d be a great read. Can anyone post it?

“It takes one to know one” 🙂

Great read1 Thanks…

This was one hell of a read! Thanks, Don!

Wow! Invaluable addition to your (and CC’s) canon, bringing more light on one of the shadiest characters in automotive history. The fact that Bracq was unaware of JZD’s machinations until you pointed them out to him is bewildering on more than one level, not least that you interviewed Bracq himself! (Call it what you want, that was an interview…)

Professor Andreina, we bow to thy exceptional contribution to automotive knowledge.

And speaking of which, what is that origami saloon below the Esprit?

Thanks T87. 1974 Maserati Medici I. It was repurposed and submitted as a possible Jaguar XJ saloon replacement. It became known at Browns Lane as ‘the gunship’. 1976 Medici II below…

brilliant article, don. this and the paul braq series are some of the best automotive histories that i have ever read.

i think a lot of the comments about delorean being a conman are unfair. i don’t get a sense that he was doing this just for his own fame and fortune. elevating automotive design was clearly the priority. he had learned the hard way at gm that cheating was required to get things accomplished.

was it really so bad to steal paul bracq’s ideas and drawings, if it would get the project built? bmw clearly wasn’t going to do it. he probably justified these things in his head by thinking of the lives that would be saved if his designs influenced the industry to more quickly adopt crumple zones and air bags.

if delorean had managed to deliver a well built car with the originally intended mid-engined rotary, his dirty tricks would be long forgotten by now.

Overall, I agree with what you say. This piece wasn’t a ‘scoop’ because in the scheme of things who cares about a long forgotten brochure. JZDL didn’t thrive in a cleanskin environment at GM; many of those at that super-executive level didn’t get there just on pure talent.

And yep, with success the end justifies the means.

I don’t agree nearly as much. DeLorean was just going with the safety thing because that was the hot subject in the 70s, and because he got that grant from Allstate. he was hardly a pioneering safety crusader in the 60s, right? GTO?

He was doing what people invariably do to get ahead, if they’re extra-ambitious: take a read of what’s “in” and run with it. We’ve seen a huge number of examples of that with the “green car” EV era. How many entrepreneurs have (and are still trying) to launch EVs and such? Do you really bevel it’s only because they are trying to save the planet?

If DeLorean were doing this today, it would invariable be an EV or such.

Was DeLorean cheering on Ralph Nader in the 60s? Me thinks not.

I thought Bruce McCall was exaggerating until I saw the ad for the pink wide track.

Great piece Don, you’ve put a lot of good work into it. Many thanks.

To me it seems like DeLorean had the same kind of appeal to the public as Elon Musk seems to be having today.

I wouldn’t exactly say that. The difference is that the DeLorean car was seen by those in the know as a significantly flawed car without any genuine new technological content, except perhaps for its stainless steel skin (not really a big deal). Rear engine? And a very pedestrian one at that? Performance? Anyhting exceptional? Poor build quality?

The Tesla was technologically unparalleled from the very beginning. Musk may have his personality warts, but his cars are absolutely world class. The DeLorean was frankly a joke; a slightly slicker Bricklin. It sure didn’t impress me at the time.

But yes, there were the suckers who fell for DeLorean’s hype. Musk may do a bit of hyping himself, but there’s invariable a substantial degree of genuine leading-edge technology and follow-through to his hype. That’s a huge difference.

Absolutely agree with this. Musk might have some personality deficiencies, but he wasn’t peddling vapourware horseshit.

Great read Don, filled in gaps in the DMC saga beautifully.

You have excelled yourself here, Professore. A virtuoso thriller. What a startling twist to fall through the fourth wall with you into a conversation with Paul Braq himself. Molto lodi, and many thanks too.

A thought recurs after reading this. I don’t want De Lorean to win.

Face-lifted, vainglorious, multi-wived, over-boasting, dealing with crooks, a charlatan. I have a perhaps-wishful belief in the inevitable demise of such types. Or perhaps not so wishful, as history shows them much outnumbered by ones who have achieved as much and more but with their human decency fondly remembered.

I am delighted you chatted to Monsieur Bracq. It is a fitting reward for your efforts on this site. He sounds like a man much at ease with the world, and with his achievements in it.

And, at the very least in the small universe of CC, you too should be much at ease in the same way.

Thanks Justy.

Having seen my fair share of these type-As in advertising, it really is a spectrum. JZDL just seemed to fall into the hazardous end of that spectrum.

You’re ofcourse right about the spectrum. For example, there are charity heads of good intention whose type-A stuff gives great results for those who most need it. (I’ll add that the edit that happened above is totally apt, and actually improves what I wrote. Cheers!)

The only pang of sympathy I have for DeLorean is reading about just how stifled he would have felt on the 14th floor. Imagine going from socializing in Hollywood with actors and socialites, to going back to Detroit and golfing with the same old executives in Grosse Pointe all the time. Oof.

Don, as always, a great read.

I’ve read a bunch of books on JZD, and I can only come to the conclusion that he was a slimy motherfucker.

CJC,

LOL! Agreed.

I can’t add anything else that hasn’t already been said. Just echoing the others that it’s a great and informative read about a man that has always intrigued me. I have read the “On a Clear Day” book, the AUWM post and others about Delorean, so it’s great to learn things that I didn’t know. And at Curbsideclassic no less!

I also always wanted one of his DMCs as a kid, but the more I learned about them, the less I liked them. Many parallels between the man and the car then I suppose.

Don, an absolutely outstanding write-up! Between this and your Paul Bracq series, I am blown away by your work. Thank you for putting in the time and effort to create these pieces.

I have always been fascinated by JZD and his history both during the GM and post GM years. This makes me want to re-read my copy of “On a Clear Day I Can See General Motors,” as it’s been many years since I read it last. I had no idea that John had “borrowed” those drawings of the BMW Turbo for his early proposal of the safety car. That is fascinating and goes to show much about the man’s character. Thanks for sharing the original documents too, I will be adding those to my archives.

JZD certainly had many great ideas and did a lot of good, but his of egotism which seemed to only grow with time certainly did him no favours. I can only imagine what he would have been able to do had he been able to keep that in check. Also interesting to hear about his little fraud scheme in his early years. Again, a good window to the core of JZD.,

Interesting that you mention that Banshee and the C3 Vette styling. This is rarely talked about, but there is no doubt the Banshee had some inspiration on the C3. Of course the Mako Shark II gets all the credit and there is no doubt it had major influenced. I dug up the below photo from the C3 styling evolution. This one was when the car was still planned to be released for the 1967 model year. Clearly the styling is between the Mako Shark II and the actual production car. Looking at this picture it’s easy to see that if you add some banshee styling features you end up with the production C3.

Again thank you Don, great work!

There was an interesting anecdote in the later, critical book on how Delorean, after leaving GM, someone very high up at AMC, i.e., a majority shareholder/chairman, made Delorean an offer to take over the company. It was a very generous offer which included letting Delorean build his sports car.

Well, the offer was from an old-school type millionaire like, say, Alfred Bloomingdale. As the intermediary tells it, Delorean had never dealt with anyone on the level of a Bloomingdale, whose word is their bond. Delorean tried to squeeze the millionaire for more money, and lost the offer. Delorean tried to recoup the deal, telling the intermediary to say he was only joking, but by then it was too late. Supposedly, Bloomingdale’s only comment was that at least they found out what kind of guy Delorean was before it was too late.

The irony is that, just a few years later, Malcolm Bricklin would come out with a car that would be eerily similar to Delorean’s, but it would have a conventional drivetrain that was, you guessed it, sourced from AMC (although later examples would have a Ford engine).

It reminds me of the career of another, larger-than-life auto industry celebrity, Lee Iacocca. Unlike Delorean, I’m certain that Iacocca didn’t mess around when offered the CEO job at Chrysler. Then, also unlike Delorean, when Iacocca found out how bad things at Chrysler really were, he stuck it out. I just can’t feature Delorean having nearly the ability of someone like Iacocca when the going got tough. IOW, Iacocca never would have tried to save a company he had started via a cocaine deal.

Interesting Story about the AMC offer, I hadn’t that one before. While no doubt Iacocca had a big Ego too, he seemed to be more of a conformist than JZD and able to adopt to the expected lifestyle that Detroit dictated.

I can’t remember the exact details of the AMC anecdote, and can’t find anything that says Alfred Bloomingdale was ever connected with the company, but it’s definitely in the book.

Iacocca was only a year older than Delorean, and their careers had eerily similar trajectories. Iacocca was responsible for the Mustang, Continental Mark III, and Mustang II while Delorean had the GTO, Grand Prix, and Vega. With that said, Iacocca certainly seemed much older, more grounded, and less prone to be seduced by the Hollywood glitterati lifestyle.

Still, imagine if Iacocca had been working for Estes and Knudson in the early sixties, and Delorean had Henry Ford II as a boss during the same time.

Thanks for that Vince. That red C3 clay answers a question for me; the XP-882 seemed to bear no cues from the C2 or C3 until I saw that pic.The trapezoidal rear window was a similar shape to the original XP-882.

Bill Collins said the Monza roadster influenced the XP-833 ‘Banshee’ shape, but it’s the XP-819 rear-engined concept that throws things out a bit. It was prepared in 1964, possibly conceived as a shape in 1963. The most overt cues of the C3 seem to have emanated from this. Now I’m wondering whether the Mako II was conceived as a shape before the XP-819 or after it.

Don, based on what I have read, the XP-819 was created before the Mako Shark II (dubbed XP-830). It seems both were created fairly close to one another though, with both started sometime in 1964. I know the Mako Shark II (XP-830) was completed at the end of March 1965, when it was first photographed, but not sure on the completion date of the XP-819.

It was my understanding the XP-819 was more of an engineering project than a styling project. It was the brain child of Frank Winchell, who wanted to prove that he could create a balanced rear engine aluminum V8 powered car. The car’s design was later cleaned up by Larry Shinoda as the initial design was rather ugly. The car itself however, proved to be extremely rear biased and had poor handling characteristics.

The Mako Shark II on the other hand was a styling project initiated by Bill Mitchell. He dictated that the car to have the following characteristics: a coupe body with a narrow slim “selfish” center section, prominently tapered tail, a blending of the upper and lower portions of the car to avoid the look of the roof being added to the car, and a sense of prominent wheels, with protective fenders distinctly separate from the main body but grafted organically. This car styling project was led by Larry Shinoda and I believe the ideas he explored on the XP-819 were further enhanced on the Mako Shark II. The XP numbers are somewhat chronological, so the Banshee would have been around this same time, bearing XP-833.

The clay I posted was again another that fell under Larry Shinoda. In the mid-60s, when they were looking for a design direction for the next generation Corvette, there were a couple of proposals. One was by Hank Haga, which was said to have a “flying saucer look” to it. Bill Mitchell hated the car and called it a “fat pig.” Larry Shinoda had an alternative design, which garnered much influence from the Mako Shark II, but with the distinction of being viable for production. Once the Mako Shark II hit the show circuit, the public reaction was enough to seal the direction for the next generation Corvette. The clay I posted was Larry’s design after it had undergone some evolution.

Fascinating Vince. Here’s my take based on what you’ve said;

1962 – Corvair Monza GT by Shinoda and Lapine, Giugiaro for Bertone Corvair Testudo being the the catalyst.

1962/3 – red Corvair roadster as shown in studio shot above within the article.

Mid-late 1963 – XP-819 rear-engine Corvette commences.

Late 1963/early 1964 – XP-830 Mako II commences out of Mitchell’s studio.

Late 1963/early 1964 – XP-833 ‘Banshee’ commences out of Pontiac Advanced Styling. As per Collin’s comment, this was inspired by the Corvair roadster. This is occurring in parallel with Shinoda’s work out of Mitchell’s studios. Neither is an influence on each other, both Mako II and ‘Banshee’ derived from Corvair language.

1964 – XP-819 is restyled by Shinoda, along the lines of the Mako II he was then working on.

1965 – Mako II presented and a success with the public.

September 1965 – ‘Banshee’ clay is pulled from Pontiac Advanced Studio and placed with Mitchell. Remembering that this car was smaller than the ‘vette; it’s hard to see how the clay could specifically be repurposed. I think Mitchell had the clay pulled out as a tacit signal to the divisions that this language was now ‘out of bounds’ as it was now to be used on the C3.

1965/66? – the red C3 clay you’ve posted. Nearly but not quite there. Mitchell uses the ‘Banshee’ now in his possession to examine some aspects such as proportioning. The rear 3/4 comparo view is unmistakeable.

Do you have any images of Haga’s fat pig?

I think that timeline sounds pretty good to me Don. I was able to dig up a pic of Haga’s car, the “fat pig” as Mitchell called it. Apparently it was well liked by Zora Arkus-Duntov though. It’s definitely not a favourite design of mine either.

There is no doubt that the Banshee had some influence on the rear styling of the Corvette. From what I read Mitchell was pushing for the fastback roofline, but for once was actually outvoted. The ’68 Vette’s rear end styling was inspired by the Porsche 904. Many thought the fastback styling was past its day and that they needed to take the car in a new direction. Take the 904 roof line and add some Banshee, and it’s not far off a ‘68 Vette.

It’s also important to keep in mind during these years there was a lot of “discussion” on which way the new Vette was going to go. I think that is the reason there seemed to be so many directions the Corvette was going with styling studies. The three options as I recall were to have the Vette heavily restyled for ’67, to have a new body on top of the old chassis, or to go with an all new mid-engine design. Mitchell wanted the second option, to keep the car front engine but have new radical body, while Zora was pushing for the mid-engine car. Obviously the first option was the cheapest, while the mid-engine option was astronomically expensive. The second option was the direction they went and was still relatively cost effective.

It’s also important that there was some discussion of cancelling the Vette all together with Camaro coming out. Some execs thought that the Camaro could fill the spot of the Vette. So, pushing hard for the expensive mid-engine car likely wasn’t viable with the 14th floor.

Here is Haga’s car:

I also found an early drawing of Shinoda’s car that competed with Haga’s car. I should also note that as Shinoda’s car evolved into the eventual C3 design, the design was altered for some practical reasons too. The fender height was reduced because of Zora’s complaints about poor visibility. There were also significant changes to help with the poor aerodynamics. Initially the car had terrible lift on the front end along with a huge amount of drag. Eventually changes reduced the drag and lift to achieve overall aerodynamics that were a slight improvement on the C2 cars.

Wow Vince, great stuff. That Haga clay answers a lot more about the first XP-882 – similar rear end treatments.

I got to thinking about the first two Corvettes; first one lasted 10 years and the second only five. I can understand why there was handwringing over what direction to take or whether to keep the model at all – sports car shapes and configurations had evolved considerably since the Motorama days. Thanks for posting this.

Don, regarding the 10 year life of the C1: the re was a very ambitious concept to replace the C1 for 1958, maybe 1959. I can’t remember its code number, but it was very much a ZAD prototype, with a monocoque body, fully independent suspension all-round, and lots of very advanced details to make it light and super-fast. Aluminum engine V8. It would have been a genuine Ferrari killer.

But it was of course too ambitious and expensive, and the plug was pulled quite late in the game. I have pictures of it on my other PC for a story I once started on the ‘Vette.

The C1 probably barely broke even in its later years; it was a money oser in its early years. That was of course the reason the ambitious projects kept getting killed.

So the fallback was to carry on with the severely aged C1, until a new C2 was conceived, substantially less ambitious than the 1958 concept. The C2 was pretty pragmatic, with frame and separate fiberglass body, which kept it from being truly world-class in terms of a sports-racer.

Obviously this same dynamic played itself out repeatedly over and over with the Vette and ZAD, who was constantly pushing for a world-class car technically (mid-engine after the C2),

Of course you probably know all this…

I had no idea about the 1958 proposal. I’ve known of the XP-700 below, but figured it was a purely a showcar introducing the ducktail so I’m not sure if this is the one you’re talking about.

No, here it is. The XP-84 dated 1957, actually, for an intended 1960 intro (I got the dates wrong, as well as some of the facts). It was to use a transaxle at the rear for perfect weight distribution, a Porsche-style body structure, aluminum V8 and a weight of 2,250 lbs. From the linked article:

Bill Mitchell suggested to stylists Bob Veryzer and Pete Brock that the styling should come from the slimness of the Pininfarina / Abarth cars with a strong horizontal line and bulges over the wheels in the upper surfaces. The pointed nose had driving lights in the grille opening and manually operated pop-up headlights. Mitchell’s Sting Ray Racer used most of the same styling ideas.

http://www.carstyling.ru/en/car/1957_chevrolet_q_corvette_xp_84/

here’s another read:

http://www.superchevy.com/features/1710-what-if-1957-q-corvette-had-become-c2-sting-ray/

The Abarth Alfa 1000 was apparently one of the prime inspirations.

Fascinating. From the description and timing, I’d suggest the 1957 PF Alfa Romeo 1100 Abarth was also flavouring that very tasty Corvette shape. No A-pillar… hehehe.

It was the Abarth-Fiat 750 that Mitchell told the stylist to draw inspiration from. Mitchell got the ball rolling by sketching a few quick lines to demonstrate the theme he wanted. According to Bob Veryzner, the mako shark that Bill Mitchell caught and mounted was also told to be an inspiration. The car had to have the powerful graceful feeling of a shark.

Interestingly, Mitchell reviewed all the drawings and selected Pet Brock’s as the sketch of choice. He told them to take that drawing and see if we can do better. Late, Brock found his original drawing had gone missing. It was only when Mitchell demanded to see the original sketch did Veryzer take it out from his desk drawer where he had hidden it.

It was my understanding the Q-Corvette basically died when Ed Cole’s Q-Chevrolet concept died. The Corvette needed to share its major components with the main-stream cars, to justify tooling costs. At least the styling theme did eventually evolve into the C2. However, the transaxle concept died live on briefly in the Tempest.

This cost reduction was seen in the production C2 Corvette. In order for the independent suspension to make production, Zora saved with a front suspension that shared many components with the Chevrolet passenger cars. Zora saw this as a reasonable compromise.

PF Abarth Fiat 750 had pretty much the same body as the 1100 Alfa. Same year too.

You are absolutely right Don. You know those cars better than I do. I just meant to share the anecdote about how the styling came about for the Q Corvette.

I did thoroughly enjoy this little discussion though even though slightly off topic.

There’s some great things mentioned here in the comments by many people. One thing that I felt that I could add (I’ve watched the DeLorean documentary), is that his usage of factories and manufacturing in Ireland very well had exploited cheap labour due to the rough economy and high unemployment there at the time, and in the end, really had angered a lot of Irish people that not only worked at the factory and got their hopes up, but people across Ireland, as a whole.

The parallels to Malcolm Bricklin are more than a few: a hustler that you want to believe in, but sells you a car that is not up to its billing (though Bricklin’s fit and finish were worse than DeLorean’s)–not to mention the Irish factory scenario seems to have been presaged by Bricklin’s controversial usage of East Coast Canadian labour and Canadian gov’t money. Plus, you have a “safety vehicle” aspiration with both stories. DeLorean seemed to pull it off on a bigger level, though.

It was a bad decision to install a factory in Ireland. This reminds me when the Rootes group had built their Linwood’s plant in Scotland or Alfa Romeo with their Arese’s factory in the south italy. To reduce the labour cost, they have set up their production in areas where there wasn’t an “industrial” culture, the local workforce was unskilled and, for me, this explains the Delorean’s poor quality,

As one might imagine, it was written that the build quality of the DMC-12 was so abysmal that the cars had to, literally, be rebuilt at the entry port once they arrived in the US. That meant that, ultimately, it cost twice as much to build, then rebuild them.

But, yeah, choosing Belfast solely due to it being the most lucrative place Delorean could find was a really boneheaded (and, frankly, rather sleazy) move. Locating in an area where labor costs would have been a bit higher but with a much more conducive industrial base would have been wiser.

Thanks for the well-researched article, gives context to the episodes I remember. Had DeLorean been truly serious about showing his former employer how to create a car the market desperately needed then, he would have directed his efforts toward a technically-advanced, high-mpg, safe, quality-built compact or sub-compact, not a vanity sports car for a segment already saturated with such choices. What a terrible lost opportunity.

It’s essentially impossible to start a new car company selling a mass-market compact or subcompact. The capital costs are an impossible hurdle. And the margins way to small. Which explains why essentially every new car company since WW2 has tried to start with a high-end high margin sports car, with which to (hopefully) build a brand: Porsche, Ferrari, Lamborghini, Aston Martin, Tesla, etc.etc.

Can you name me one new mass-market new startup, in the US or in Europe after 1960 or so that didn’t fail early on? It’s essentially impossible to compete against the large companies on their turf.

The fate of Kaiser-Frazer is sort of a case in point.

And K-F was actually targeting the more lucrative mid-price segment of the market (as you know, of course). The Crosley fared much worse.

Though I suppose such a compact effort would have been underfunded and ended in failure, DeLorean had the support of the British government at the time desperate to create employment in Northern Ireland. For this reason, they might well have supported the start-up and years to establish the product footings until it proved successful. Subsidies have been utilized to established other fledgling automotive ventures, better it should have been tried with a mass-market car.

DeLorean’s support from the Brit. govt. was also highly limited, and a big gamble and stretch as it was. Building a mass-market compact would have required financial support many times over, which the gov.t really didn’t have. They were already up to their eyeballs in automotive hell with BL.

How could they possibly have garnered political support to build a car that would directly compete with their own BL compacts? Sheer insanity.

Sorry, but there is absolutely no argument that can be made to support such an undertaking that can be backed up with some other precedent. Look how well Proton made out, and that’s in Malaysia.

I just thought of the one precedent: Saturn! Although the initial few years’ of their cars sold reasonably well, GM overall lost somewhere between $10-12 billion, which is closer to $20 billion in today’s dollars.

Saturn turned out to be the K-F of the modern era, but was backed by GM, and it also turned out to be one of the coffin nails that eventually killed GM.

The mass market is and has been way too competitive to support the overwhelming capital investment needed. Automakers already have been struggling with the poor returns on their capital for decades; ever since the 1960s, actually. There is no investor or government crazy enough then (or now) to back such a massive undertaking.

Meanwhile, small, high margin exclusive startups have a real shot at making it. Think McLaren. And Tesla.

There’s a reason FCA is bailing on mass market cars and putting all their investment in their high margin premium brands. And their not the only one.

K-F had Reconstruction Finance Corporation to thank for getting even as far as they did. Given how much they loaned to K-F, apparently the loan managers weren’t familiar enough with the auto-making business to grasp that ultimately K-F would fail versus the Big Three.

Of course, with the divorce of Joe Frazer from active management after the 1949 model showdown, the corporation in the hands of clueless Edgar Kaiser with no depth of automotive management experience dooming K-F for that day forward.

On Tamir Ardon’s Delorean website, there’s a very good Inc. article published not long after DMC went under (April, 1983). In it, it’s suggested that Delorean might have been able to hang on for a bit longer if not for two things: 1) when the market for the cars began slowing and money was running short, instead of cutting back production, Delorean actually demanded it be doubled. It was the old GM mentality of, when the going gets tough, the tough just sell more cars. I vividly recall how the liquidators still couldn’t sell the unsold cars at the reduced price of two times the price of a Corvette (the original MSRP was three times a new Corvette).

And, 2) Delorean himself was such a public dick towards the British government when they showed the least bit of hesitancy on giving him any more money. Instead of acting a civil gentleman (which is what the British respect), Delorean, instead, went the ugly American route and complained loud and long to the press about it. It pretty much cemented the British government giving a him a resounding “No!” to any more funding, and doomed the company..

So, it was Delorean, himself, that ultimately killed his own auto business.

I should say for the record that I’ve had only very limited direct contact with Tamir Ardon, but his site is really an astonishing resource for anyone interested in DeLorean’s career. Tamir has gone to extraordinary lengths to track articles on DeLorean, not just in automotive magazines, but in other contemporary periodicals — of which there ended up being quite a lot, given his notoriety.

Another excellent book for those interested in further study, though hard to find in the U.S., is Cork on Cork, by Sir Kenneth Cork of Coopers Lybrand. Sir Kenneth dealt with DeLorean when DMC went into receivership, and his perspective on the situation really helps to set into perspective the precariousness of the company and the extent of DeLorean’s wheeling and dealing to try to get out of it.

A magazine ad I remember seeing in 1980:

It has been a perfect cold wet winter Sunday to absorb this magnificent story, thank you Mr Andreina.

I even discovered a brand of tyre I had never heard of, Englebert,(seen on the gull wing Mercedes)

Until this time I thought Englebert was just a made up name by a singer in the 60s, a name that gave me a lot of amusement as a kid.

Englebert the tyre maker linked up wih Uniroyal but is now no more.

You found his first name funny when his second was HUMPERDINCK?

I noticed the tyre too, and admit I did muse for a second if the rear might read “Humperdinck”.

It didn’t come across in my comment, but it was his second name that gave me the laughs, and I must confess it still does. 🙂

Of course, you know that’s not the singer’s birth name, don’t you? He was born Arnold George Dorsey. He was given the Humperdinck name by music impresario Gordon Mills, who also gave the world Tom Jones (birth name: Thomas John Woodward). Mills swiped the name from a 19th century German composer, best known for the opera Hansel and Gretel.

The BMW looks better to me after all these years. The Delorean looks unfinished, truly clunky.