(first posted 10/15/2016) Few French designers have left their mark on as many cars, trucks and other products as Philippe Charbonneaux. His only real rival would be Raymond Loewy, but Loewy was based in New York. Charbonneaux’s automotive designs ended up on production cars and trucks made by about ten different companies. He also created an incredible array of unique vehicles, from presidential limos to publicity trucks, as well as prototypes and coachbuilt specials.

The self-taught Charbonneaux also designed refrigerators, television sets, motorboats, toys, lamps, alarm-clocks and toothbrushes. He was an accomplished painter and illustrator, producing cover art for the automotive press or for automakers’ brochures, as well as dozens of design studies during his short stint at General Motors. Let’s focus on the vehicle-related part of his career.

Amiot 350 bomber in French colours – artwork by Charbonneaux.

Philippe Charbonneaux was born in the city of Rheims, 80 miles east of Paris, in 1917. He was a useless student, spending most of his waking hours drawing airplanes – his first passion. When on periodic leave during his military service in the French Air Force (1937-39), he would spontaneously visit the top Parisian coachbuilders to present his first car designs. Nothing came of these endeavours, though he got himself noticed. Charbonneaux fled to England in 1940, enlisting as a “Free French” volunteer in the RAF and was sent back to France in 1943 to spy on the Luftwaffe’s activities there. He married that same year.

1946 and all that…

After the war, famed coachbuilder Jacques Saoutchik recommended him to Delahaye, who were preparing a new model for the 1946 Paris Auto Show and tasked Charbonneaux with designing the car’s front end.

The new Delahaye’s visual identity: vertical “fencing mask” grille, inboard headlamps, triple horizontal slits.

Like Rolls-Royce, Delahaye only made engines and chassis – customers would then pick a coachbuilder to execute the body of their choice – but required a measure of visual identity: the cars’ grille and overall front fascia.

The Delahaye 4.5 litre chassis as it appeared at the 1946 Paris Auto Show.

The 4.5 litre Delahaye 175 / 178 / 180 series that debuted at the Salon de l’Auto in October 1946 bore Charbonneaux’s first major design job. The car wasn’t even given a body due to time constraints and the manufacturer’s wish to show off the new chassis’ relative modernity (Houdaille shocks, De Dion rear axle, “Dubonnet” independent front suspension, hydraulic brakes, left-hand drive, etc.) and its massive new engine.

1947 Delahaye 135 cabriolet by Pourtout, sporting the new grille.

The carrossiers usually respected the grille design specified by Delahaye (though not every time); Charbonneaux soon updated the pre-war 3.5 litre models (135 / 148L) to look similar to the new 4.5 litre range, minus the horizontal slits.

Page from the 1947 Delahaye 180 brochure by Charbonneaux.

The designer branched out as an illustrator, drawing the Delahaye and Delage catalogues for 1947, as well as several front pages of magazines and advertisements.

The new prodigy’s renown spread quickly. He was approached by racing driver Jean-Pierre Wimille, who had an idea for a completely new car: a mid-engine three-seater with central steering and an aerodynamic body. In 1946, Charbonneaux designed two prototypes for Wimille to test out on the roads. The racecar driver was working on a 2-litre V6 for the car, but the first prototype had to make do with a 56hp Citroën Traction motor. It still managed to reach 150kph (30 more than the Traction).

The second prototype (1948) used a Ford 2.2 litre flathead V8 just ahead of the rear wheels, as the V6 still wasn’t ready. But tragedy struck when Wimille, still an active racecar driver, fatally crashed his Simca-Gordini in Argentina in January 1949. The project was stillborn, though it was exhibited as a posthumous homage at the 1950 Salon de l’Auto (top photo).

One of the many sketches Charbonneaux drew during his stay in Michigan. Source: leroux.andre.free.fr/charbonneau.htm

From April 1949, Charbonneaux spent six months in Detroit working for (but never actually meeting) Harley Earl, sketching futuristic sports cars. At the end of his trial period, he went back to Paris as he disliked GM working methods, preferring to be involved with the totality of a car’s design than doing endless sketches that might be rehashed down the line by others.

One of Charbonneaux’s “Corvettes.” Source: as above.

“At that time, American styles were heavy, with enormous hoods and low fenders. During the time I was in Detroit, no design, no clay model besides mine proposed the notion of front fenders higher than the hood, which was itself flat. My intervention became the point of departure in the studies that resulted in the first Corvette.”

Our man many years later, in his museum, sitting in a 1953 Corvette.

This is a highly contentious claim, as anybody in the business (e.g. Earl, Bill Mitchell, etc.) would have known the latest Italian creations also featuring the high fender / low hood combo, such as PininFarina’s 1947 Cisitalia 202. Nobody who was at GM styling at the time has supported Charbonneaux’s assertion.

Charbonneaux was contacted by Rosengart, an ailing firm that had botched its reentry into the car market after the war, upon his return to France. The designer did what he could to improve the new Vivor’s front end and also produced the marque’s publicity material.

The dated Vivor wasn’t selling (1200 units in two years), so Rosengart asked Charbonneaux to completely re-body their pre-war chassis. The Ariette was the rather attractive result, produced from 1951 to 1953. It sold a bit better than the Vivor, but not enough to save Rosengart from oblivion.

1951 Delahaye 235 by Letourneur & Marchand as per Charbonneaux’s blueprints, with the designer-owner himself.

Delahaye came calling again for their newest (and, it turned out, final) car: the 235. This time, Charbonneaux imposed a modern design on the arch-conservative firm: horizontal grille, integrated headlights perched atop the fenders, full pontoon styling. Of course, these details were not compulsory for the dwindling Delahaye clientele, who could specify whatever they wished to their selected coachbuilder. However, all 84 cars produced (1951-54) ended up with Charbonneaux’s front fascia.

For comparison, this 1953 Chapron coupé, though different, keeps the 235’s signature front styling.

Putting a test car together was a hectic job. The 235 urgently needed its Charbonneaux-penned body so it could be tested and ultimately homologated (i.e. receive the French authorities’ consent for production). Delahaye wanted the body made in three weeks – too short notice for Letrouneur & Marchand, one of Delahaye’s favoured coachbuilders. In early 1951, an older Chapron body was quickly mated with the prototype chassis and driven to carrozzeria Motto in Turin by two Delahaye engineers and the designer.

In 1953, this other Motto 235 was driven from Cape Town to Algiers, setting a new record (11 days and 5 hours).

The car came back with its new Motto aluminum body by road three weeks later and could be used for testing and certification purposes. But Delahaye’s head engineer soon cursed: “Charbonneaux, you bastard! Your aerodynamic body’s very nice and all, but now we have to re-do the brakes.”

Magazine cover art by Charbonneaux depicting the Delahaye 235, July 1951.

Letourneur & Marchand, Antem and other coachbuilders soon produced their own versions of the Delahaye 235, which debuted at the 1951 Paris Auto Show. It was lauded as an exceptionally good design, though the “re-done” brakes were still (lamentably) cable-operated…

A Caravan of Weird Heavies

Throughout the ‘50s, Charbonneaux’s independent styling bureau was called upon to design special cars and trucks on a variety of chassis. The bureau was create in 1953 and comprised a small team headed by Charbonneaux, who took a number of promising young talent (such as Paul Bracq) under his wing.

Long-distance bus sketch, 1955.

Let’s look at the trucks first, which were usually made for the Tour de France’s “caravane publicitaire”, wherein all sorts of industrial concerns distributed their products directly to the crowd on the roadside, usually straight from bizarre purpose-built affairs.

1952 publicity truck for a laundry detergent brand on a Delahaye 163 L chassis, body by Heuliez.

Renault R-2061 truck with a cool and fizzy Letourneur & Marchand body, also dated 1952.

Closed / open “Astra” (margarine) truck on a Delahaye 163L chassis, coachwork by Le Bastard (!) in 1954.

Teleavia and Frigeavia were brands owned by Sud Aviation, hence the jet theme. Charbonneaux also designed a TV set and a refrigerator for these marques. This 1955 truck is based on a Citroën U55 chassis with coachwork by Leffondré.

Another Citroën U55 chassis with pointy Le Bastard body for the Bic pen company in 1955.

Charbonneaux also designed this extraordinary mobile radio studio for the ORTF (French public radio & television) in 1953 on a Panhard IE 45HL chassis.

The body was executed by Antem. The vehicle was used for a few years to report on the Tour de France and bought back by Charbonneaux in the ‘70s, after having been used by a circus. It was comprehensively restored and became part of his impressive car collection, which preserved many of his iconic creations.

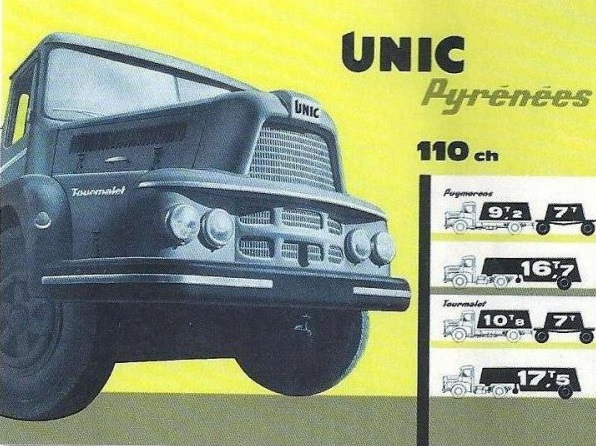

At the end of the ‘50s, several truck-makers called upon Charbonneaux to design new cabins for their products. The designer notably worked for Unic’s ZU range (1956, above), the Willème “Horizon” cabins (1959, below) and the Bernard TDA (1960, bottom). These were all mass-produced into the ‘60s.

By Appointment To Monsieur Le Président De La République

There were also interesting Charbonneaux one-offs on car chassis. Some of them quite proletarian…

In 1953, Charbonneaux designed this special on a Citroën 2CV (Antem coachwork) for a champagne maker and port wine distributor. The body was reputedly so heavy that the car was nearly impossible to get going.

Citroën 2CV coupé designed in 1955 – two were made by Pacaud, a small provincial firm.

… Other designs were more aristocratic, but bearing the same chic.

This 1954 Salmson 2300 S barquette had plastic coachwork by Antem. Charbonneaux’s style on cars was getting edgier by the mid-‘50s – though this did depend on the client…

Charbonneaux was called upon to design a presidential limousine on a strengthened Citroën 15-Six H platform. The body was built by Franay and exhibited at the 1955 Paris Auto Show. To minimize costs, Charbonneaux cleverly used parts from production cars: the windshield of a Ford Comète, Chevrolet tail lights, etc. The car was in service with the Elysée until the mid-‘70s.

Source: leroux.andre.free.fr/charbonneau.htm

When the Elysée called on Simca to provide a new parade car in 1959, Charbonneaux presented this design on a Vedette platform. Simca preferred to keep the production car’s styling, for reasons of cost (likely) and to better advertise their brand (very probably).

Finally, a car has been mentioned on CC before, the ill-fated attempt by Renault to reclaim the presidential imprimatur, a drum roll please for the 1962 Renault Rambler by Chapron.

1938 Suprastella – back when Renaults were fit for a king (in this case, George VI)…

Renaults had been the usual choice for presidential cars once upon a time, when their massive straight-eight cars were deemed appropriate for the Elysée. But Citroën (and, to a far lesser extent, Simca) nicked Renault’s place in the ‘50s.

187 rounds fired, 14 hits on the car, two tyres blown – zero victims.

In August 1962, De Gaulle and his wife had a brush with death when their DS was sprayed with machine gun fire at the Petit-Clamart. Minister of the Interior Roger Frey took the initiative of commissioning an armoured car. Renault, which was then assembling AMC Ramblers, grasped the opportunity with relish.

Rear shot of the armoured Rambler. Still terrible.

Not Charbonneaux’s finest effort… To be fair, it was rushed and the Rambler chassis was probably too narrow for an armoured car, which also had to have large triplex windows so the 6’5’’ president could sit comfortably and be seen. Chapron made the body to Charbonneaux’s specs in record time, and the car was ready for service by late 1962.

Perhaps intended to scare away the terrorists?

But no one had told the president. Going out for dinner one evening, he saw the Rambler parked downstairs and blurted out: “What is this atrocity? I never ordered this! Whoever did can pay for it – it won’t be paid for by the Republic. Bring me my car.” The Franay limousine or a standard DS were used instead that evening; De Gaulle probably never even sat in that Rambler.

The Renault and Berliet contracts

Renault had asked Charbonneaux to do that rush job on the Rambler because he had done so well for them in the recent past: he had “saved” the R8.

In September 1960, Renault called Philippe Charbonneaux to the rescue on that project after the previous Italian stylists threw up their hands in desperation and headed back home. (It is not known for sure where these “Italians” came from, but Renault did a lot of business with Ghia in those days.)

The designer was brought to a secret warehouse full of Renault protoypes in Reuil-Malmaison and presented with the R8 prototype as was: a complete mess with virtually no redeeming qualities or good angle. “I was given carte blanche for one month, alone with a dozen of some of the best panel beaters in France.” Charbonneaux worked without drawings and could not change the basic structure, but he did, with his flair for detailing and metal creases, manage to render a boxy but rather attractive shape.

From then on, Charbonneaux was on retainer for Renault. Working with Gaston Juchet and a clutch of other stylists, he set to define “Project 114”, the next large car. Renault had nothing in that segment at the time since the Frégate, which had been put to rest in 1960 without a successor. Several in-house proposals were developed, as well as a Ghia prototype (above), though none were particularly good-looking. These all came to naught in the end, as the 2.2 litre 6-cyl. was deemed too heavy and as lymphatic as the Frégate’s 4-cyl.

Renault changed tack and aimed a little lower with “Project 115”: a 1.5 litre 4-cyl. FWD hatchback. Charbonneaux worked on what became the Renault 16 with the design team. It was allegedly his concept to build the R16’s body with three basic pressed steel panels (left side, right side and roof, bolted to the platform). However, our man’s strong temperament and dislike to being beholden to any one company meant he soon reclaimed his independence.

Gaston Juchet working on the R16 clay model.

At only 31, Juchet took over as head of Renault’s design studio in 1963 and finalized the car’s styling. It is a matter of some discussion as to which designer, Juchet or Charbonneaux, should be considered the R16’s creator; some courageous automotive historians credit both men.

One of Charbonneaux’s ideas for the Renault 16 was to create a two-door coupé / cabriolet. One was made in 1964 but the project never made it to production.

After it came out in 1965, Charbonneaux proposed this notchback version of the Renault 16, should the public be averse to its revolutionary hatchback design. Renault (wisely) turned it down.

After leaving Renault, Charbonneaux was invited to devise a suitably avant-garde cabin for Berliet’s new air-sprung truck, the five-ton Stradair (1965-70).

It was certainly distinctive, probably second only to Bertoni’s Citroën “Belphégor” as the most iconic French truck of the ‘60s. It was also highly innovative, with its low “car-like” cabin, but stifled by new regulations regarding front overhang size in this tonnage.

On The Sidelines, Looking Askew

In 1969, Charbonneaux applied his craft to Jean-Albert Grégoire’s latest creation, an electric car. The small CGE (Compagnie Générale d’Électricité) Grégoire panel van was built of fiberglass by Chappe & Gessalin in about 20 units until 1972 and used in cities by EDF, the state-owned power company.

From 1969, the designer got more involved in the automotive press, editing until 1975 one of the first French-language magazines dedicated to classic cars, L’Anthologie automobile, and providing content and illustrations for his and other publications.

Source: leroux.andre.free.fr/charbonneau.htm

Among the designs Charbonneaux intended more for the pleasure of the eye than serious production, this somewhat Amercian-tinged Delage artwork demonstrated that he favoured the Virgil Exner school of neoclassical design, even as early as 1963.

How does it compare to Exner’s 1965 Bugatti 101 or his 1966 Duesenberg in your eyes?

Although he never officially retired, Philippe Charbonneaux was not involved in any more creative work with any large automaker save for one last project. He and swiss coachbuilder Franco Sbarro made a three-volume sedan version of the Renault 25, which was admired at the 1985 Geneva Auto Show. The Mercedes-like styling was stately, but Renault would not grant this transformation with an official warranty.

Ellipsis I with its designer at the wheel, 1992.

In his seventies, Philippe Charbonneaux devoted his energies towards a completely new type of vehicle, the Ellipsis. He created several of these interesting rhomboid vehicles, the first of which was powered by an air-cooled Volkswagen 1600 driving the middle wheels. Steering was by both the front and back wheels.

Ellipsis VII at the Rheims museum next to its sibling, the Ellipsis City bubble car. Photo: Wikipedia.

Though not all Ellipsis were roadworthy, the seventh and final Ellipsis (1997), a three-seater with a central driving position (just like the Wimille prototypes of 30 years prior), was powered by a Porsche 911 flat six. Its extremely low Cx (0.14) and low weight could have enabled it to reach 300kph. Nobody dared to try and verify this. Its carbon-fiber and Kevlar body was made by Sbarro.

A “contemporary” Facel-Vega sketched for the marque’s owners club. Source: leroux.andre.free.fr/charbonneau.htm

Most of the Ellipsis work was self-funded. The designer had collected over 150 vehicles over the years, including those he had created, and opened a museum in Rheims. In 1997, some of the collection was sold at an auction. But a good chunk of the collection can still be seen today in Rheims and some of the most interesting designs were exhibited at Rétromobile earlier this year. Philippe Charbonneaux passed away in 1998, aged 81.

Fascinating read of an industrial designer I don’t think I’d heard of before! Loewy, of course, consumed a large portion of our ID History classes at uni. Thanks for the writeup!

The Italian influence on the R8 is likely the stillborn Alfa tipo 103 FWD prototype – Alfa and Renault shared a licencing agreement around this time. The R16 was said to be the result of espionage stolen from a Citroen project. If you go to juchet.fr you will find development sketches in the abstract of the distinctive elements that became the R16. I don’t think either Juchet or Charbonneaux personally stole this shape, but I think Juchet is the one who Renault-ised it. I do prefer Charbonneaux’s R16 coupe to the five door, though.

An indispensible biography, Tatra87. Many thanks.

Cheers Don — knew you’d appreciate this… 🙂

Re: the Alfa connection, I’m a little doubtful. Alfa and Renault did do business together in those days (Alfa assembled and sold Dauphines in Italy), but I don’t think they shared R&D info. And though the Alfa 103 does have a similar three-box shape, that was also the case for a number of smaller cars back then — Simca 1000, Lancia Fulvia, VW 1500, etc. Convergent evolution, I suspect… Ghia and Renault were pretty close collaborators throughout the 50s, so as I said in the text, it was probably Ghia stylists who were working on the R8.

Citroen’s infamous claim of industrial espionnage was more of their typical paranoid Michelin-era BS. See the pic below: Ghia’s initial work on project 115 in 1958, way before Citroen’s ill-fated “Project F”. Very interesting, when one considers the R16: everything is basically there. Six light hatchback with a slightly beak-like grille. This was done neither by Juchet nor Charbonneaux, though it seems Juchet produced pretty much all the drawings for the R16 — those that survived in Renault’s styling bureau archives (where Juchet worked for 30+ years), anyway…

The Citroen F did look like a badly drawn R16 — “what really killed it,” according to Citroen fan-boys, was that Renault patented the welding method for the roof / side panels of the R16. Citroen claimed (with zero proof) that they had come up with it first, but did not patent it for fear of tipping their hand on their new model. Paranoid reasoning of the worst kind. If Citroen were so advanced, they would have launched their car first, right? It took them over a year to can the F (April ’67). How does that make any sense either, btw?

Truth is the F was badly behind schedule, the Wankel engine wasn’t ready, the flat-four was underdeveloped, the body wasn’t rigid enough, the styling was dreadful, the aerodynamics were terrible and the car did not handle well. It was an absolute turkey and they were right not to have made it. But they were sore because Citroen management took far too long to decide to kill the F, by which point they had already paid Budd for some of the body tooling. They lost a small fortune on the F, and that loss snowballed into Citroen going bankrupt in 74. Blaming Renault for getting their car right is just sour grapes.

Thanks for that overview on the F. I’ve been relying on the Citroenet account of things so it’s great to get your perspective.

Re: The R8. You make a solid case for Ghia, and I’ve just found a recollection of the 103 by Giuseppe Busso which does not mention Renault (and in fact mentions Peugeot for some engine technology sharing around this time), but I still feel the 103 led to the R8. Most telling for me is the dihedral dip in the front deck/bonnet panel and the creased boxiness that is not apparent on the Simca 1000, Fulvia etc. Taking into account the Ghia 115, as well as the 900/Selene and Ghia Chryslers, I still can’t see that the R8’s adroit box shape emanated from the carrozzeria in the mid to late 1950s. Hmmm….

Is it me or does that Citroen F have a front end inspired by the Rover 2000 (P6)?

A subtle payback for Rover and David Bache using the DS as inspiration?

A fascinating life and career. The true independent designers were rare even in those days.

It looks to me like the Astra Margarine truck grille and headlights are a 51 or 52 Ford truck unit that’s been flipped upside down and modified.

“… a flair for detail and metal creases”. The R 8 is one of my favorite car designs because of these metal creases. I had no idea who the designer was and what he had to deal with.

TATRA87: Thank you so much for this article!

Very in-depth and informative! Can you do a similar write-up on Robert Opron?

Hmmm… now there’s a thought… I’ll see what I can do!

Seconded!

and thirded!

Very comprehensive article and your diligent research is quite obvious. This was a great read!

+1

Really enjoyed this….more please. I have a fascination with design and with automotive design in particular. I did not know of Charbonneaux, and I find his work very very interesting.

Lots of neat stuff here. I like the Astra truck with the pop top and the jet-styled truck that (if you removed the wings) looks like an even more futuristic GMC Motorhome but predated it by 18 years. The Delahayes are gorgeous as always.

Also curious about the television set in the second photo. I always thought the iconic Philco Predicta TV with its exposed tube atop a separate chassis was one of kind, but it didn’t arrive until a year after the 1957 Charbonneaux-designed set shown here.

At that time French TV had only one channel and went off the air by 10pm. Daytime? Forget it. At least it was interesting looking and a topic for conversation.

I have a theory: Continental European TV was intentionally boring so viewers wouldn’t get hooked on the “Idiot Box.”

Great writeup. Would love to see similar retrospectives of other car designers.

Another fine CC article that made my day on a day that needed to be made. Those busses and trucks are, well, unique…..Sort of A French version of GM`s Motorama.

Terrific writeup of a esigner that I’ve coma across here and there but never in a complete way. I learned a number of new things, for a change. 🙂

A remarkable CV covering such a wide spectrum. Including such splendid designs and a few real stinkers (that R16 notchback being a notable example).

Those large vehicles, trucks and buses are quite the display of 50s optimism. And some of those design elements made their way into French locomotives. Maybe he designed some too?

Thanks for this great addition to my knowledge and our archives.

You’re welcome – fun to write these, actually.

AFAIK, he never designed any rail-related vehicle. But I know what you mean about the locomotives: the “broken nose” locos (“nez cassés”), right? Paul Arzens designed those.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Locomotives_Nez_cass%C3%A9s

Yes. I didn’t know that’s what thy were called, but I see why.

Paul Arzens’ work would make another interesting subject too. His 1930s/40s concept cars were quite stunning if unlikely to become production vehicles.

Charbonneau may have disliked corporate editing, but it’s fortunate that he worked within the corporate structure most of the time. His edited and processed designs are excellent, and his freely drawn one-offs are horrible. (This seems to be typical of many famous designers.)

Interesting info about the creases on the R8. They were definitely the saving grace both esthetically and mechanically.

I agree with many of the comments here, a great write up Tatra87.

I don’t think the question of the R16’s origins relative to the Citroen Projet F will ever be satisfactorily answered, but there are very definite similarities in the design and the construction process, enough for Citroen to abandon it and go with what eventually ended up as the GS.

http://www.citroenet.org.uk/prototypes/projet-f/projet-f.html

Agree with Paul on that R16 notchback, it is hideous, though it’s sloping tail and the angle around the base of the c-post is strangely reminiscent of the Peugeot 504.

“Le Grand Charles” in a Rambler? That just ain’t right!

No it sounds wrong on all sorts of levels but Ive heard of these French Ramblers before so maybe big Charlie did ride in one.

What a great write up! Went perfectly with my second cup of tea. Thanks!

Interesting writeup, thanks!

That pretty Amiot bomber is an example of how the French were better at designing combat planes than building them, hence their prewar procurement of American types like the Douglas DB-7, Martin 167, & Curtiss Hawk 75. Britain wound up “inheriting” French orders after the Fall.

Thank you, wonderful. The usual suspects, reconnected and expanded by another name.

Fantastic article about a designer I should have known but didn’t. Aside from an Automobile Quarterly article from 1989 – which I’ve just ordered – nothing about him written in English, and only 2 very expensive books in French. Is there a website about him, or for the museum?

Also really wish someone would do a history on the caravane publicitaire trucks. I’ve come across these from time to time, and they’re a fascinating combination of both design and advertising history.

Thanks for your kind words. I do try to pick subject matter that may be hard to find in English. It’s my “added value” for CC as a bilingual writer, I guess.

There’s not too much out there in French either though. One key source mentioned in the text is Leroux’s page ( http://leroux.andre.free.fr/charbonneau.htm ), but I had to dig into each model quite a bit to find relevant tidbits about the designer.

And with a character like Charbonneaux, you have to take some of what is said (by him or people who write about him) with a grain of salt. Interesting article (in English) about the Corvette controversy: http://marieharris.com/corvette-fever-november-1989/

Museum website: http://www.musee-automobile-reims-champagne.com/en

The 1955 bus design is a striking rendering. The bus it depicts is mostly just odd, but as a piece of graphic design, it’s outstanding.

Great write up and an interesting guy he had a hand in lots of things that always bore a passing resemblance to each other now I know why it was the same guy waving the pen in all of them, I third an article on Robert Opron.

An old picture (1993 or 1994) with P.Charbonneaux. The car is for the Eco Marathon Shell with the Reims IUT (university of technology):

Terrific piece that deserved a longer second reading.

Those 50s and 60s trucks and buses are truly brilliant, still French, modern, attractive. You can elements of these designs in the recent posts we have had from bus and truck rallies in Europe, and any good French market will still have vans that are clearly evolved from these styles.

Bu the Renault 16 was bets ass a hatchback

Left to read late because at first glance the article looked to warrant careful attention. Glad I did, so thank you for the great read.

As an aside, I’ve come across a brochure for the 67 Rambler Renault. Obviously in French, black and white except the solid colour of the covers, matter of fact images make the car look very austere. Leaves me wondering just what the intended market was.

Fascinating article. Does anyone know what the Elipsis cars were like to drive? One can imagine they’d have needed some development, but they must have been very handy in town- tight turning circle indeed!

Hello

Great overview!

Can you please let me know the source of the BIC promotional vehicle picture?

Thanks

I fished it out the rich seam of weird photos called Caradisiac, a French site.

https://forum-auto.caradisiac.com/topic/374819-topic-des-publicitaire-et-des-carrosseries-speciales/page/31/

The Astra margarine truck, in its open configuration, reminds me of a Chevrolet Corvair Greenbriar pick-up. Was it (the Corvair-based truck) also called a Rampside?

God bless Charboneaux (and you). From now on ” industrial designer” will become “esthéticien industriel” in my writing.