For today’s CN, we’re going to tackle a big issue that I have been meaning to bring up here for years: Why the Japanese never made the huge inroads in Europe as they did in North America. I’m going to dig out a musty old copy of a 1995 New York Times with a relevant article I’ve been saving for this occasion, and I’ll add some commentary before and after. You did stop by to hear me talk, right?

There’s no question that the Europe auto industry in the 80s was deeply concerned (i.e. scared shitless) about the prospect of a Japanese invasion the likes of which had been playing out in NA in the late 60s, 70s and 80s. The Europeans watched in real time as Detroit was decimated by Japanese cars. And they participated too, initially with the VW Beetle and then with their rapidly growing imports of German premium brands.

Of course the two markets were very different. The Japanese exploited the fact that the American Big Three had become very complacent about building small cars (think Vega) as well as the quality of their cars in general. And cheaper European imports like VW and Opel were getting reamed by the dramatic fall of the dollar’s value beginning in 1971. This set the stage for their ascent.

But unlike Europe, with its many tariffs and other trade barriers, Americans had always been very friendly to imports. There was/is only a very low 2.5% import tariff, and in the immediate post-war era, the general feeling was that buying European imports was helping them get off their knees. And Americans were just very open to the whole idea, as many buyers felt constrained by the lack of variety and range of sizes offered by the American makers. The American auto press and media in general was always very fair to the imports, if not even fawning, and there was generally very positive media coverage. It all lead to a most welcoming attitude, and in 1959, imports captured 10% of the US market.

Although that dipped a bit for a few years starting in 1960, it wasn’t long before it was back to that and more, especially once the Japanese entered the market with more competitive cars in the mid-late 60s. This expansion continued rapidly until the mid 80s, when it became obvious that it was impacting the domestic industry quite significantly. That led to the 1980 Voluntary Export Restraint (“VER”), whereby the Japanese agreed to limit exports to an agreed amount for some years (1.86 million per year, initially). That led to the japanese building plants in the US, as well as the unintended effect of raising prices on all cars, creating a huge windfall for the Big 3 at the expense of consumers. But this was really just a temporary blip in the continued growth of the Japanese market share in the US.

As the following article details, various European countries had or raised much more challenging import barriers. But there were other ways the European industry fought back, especially in Germany. I’ll get to that after the article.

originally published in the June 28, 1995 NYT

Switzerland’s difference from the rest of Europe is clear in a Japanese car showroom here.

At Rolf Wirnsberger’s dealership, a smart little two-door Mitsubishi Colt sells for a little less than $14,000, about $7,000 less than a comparable car, say, a Volkswagen Golf. In Switzerland, the Colt sells relatively well. Not so in Europe’s largest auto markets — Germany, France and Italy, which have effectively limited the sales of Japanese imports.

While Japanese car sales in the United States accounted for about 23 percent of the market last year, in Europe they were half that amount.

The Europeans have limited the sales of Japanese imports by allocating market share and growth rates. They have also forced the Japanese to accept other trade barriers as a price of entry into the world’s second-largest auto market.

Indeed, the tough European trade stance has squeezed the same kind of concessions out of Japan that Tokyo is reluctant to grant the United States. Thus the Europeans have demanded — and gotten — larger quotas of European-made parts in Japanese cars built in Europe, and have forced Tokyo to accept what are in effect market quotas for its cars in Europe.

For years, many European auto markets were kept off limits to Japan thanks to an array of bilateral government agreements, some of them going back decades. Italy, for example, signed a mutual restraint agreement with Japan after World War II that enabled Japan to protect its market from a murderous flood of cheap tiny Fiats. In recent years, the accord served Italy to keep the Japanese at bay.

In 1992, as Europe moved toward a more open market, European trade officials agreed to gradually allow the Japanese a greater portion of the market. But when sales slumped the next year, and European car makers feared a permanent loss of market share, Japan was forced to back off and accept slower growth. In exchange, Europe agreed that it would lift all restrictions by the year 2000.

“It’s totally managed trade,” said Jeffrey Bobeck of the American Automobile Manufacturers Association in Washington.

Under the arrangement, officials from European trade offices and Tokyo’s Ministry for International Trade and Industry meet twice yearly to review car sales forecasts, after which the ministry assigns quotas to the Japanese manufacturers based roughly on their existing European market shares.

The aim is “not to upset the market, but to assure smooth growth,” said James Rosenstein, the spokesman for the Association of European Automobile Makers in Brussels. “The spirit is a fair sharing of both growth and contraction,” he said.

In Italy, for example, where Fiat has had to struggle to stay in the race, the Japanese share has been held to about 5 percent; in France, where auto makers Renault and Peugeot have effectively lobbied the Government for protection, it is less than 4 percent.

Dealers like Mr. Wirnsberger in relatively open markets like Switzerland are lucky. With no competition from a Swiss auto industry and few import restraints, Japanese cars have seized 24 percent of the Swiss market. In Ireland, their share is 37 percent, in Finland 29 percent, and in Denmark 26 percent. Even in relatively liberal Britain the Japanese share hovers at 12 percent, half the North American figure.

Japanese auto makers started making cars in the United States largely to get around voluntary import quotas that Japan agreed to in the early 1980’s. Similarly, the Europeans have forced Japan to agree to build more cars here.

But unlike the United States, Europe got Japan to agree that any cars made in Europe would have at least 60 percent of their content supplied by European parts makers.

For that, the Japanese have taken the costly step of recruiting and training European suppliers. By this year, Nissan and Toyota, which also build cars in Britain, say local content will surpass 80 percent. In the United States, American-made parts account for less than half the content of Japanese cars made in America.

The Japanese have also been hamstrung by a European system of car dealerships that was almost as highly regulated as the Japanese system that has foiled American car makers. In Europe, it is virtually impossible for the Japanese to sell through existing dealers. Only last week, the Europeans announced a partial deregulation that would make things easier for non-European auto makers.

Nevertheless, the Japanese are far from dropping out of the race.

Really? One already has (Daihatsu). We’ll check in on that prediction a bit further on.

There’s more to this story about the issues the Japanese faced than the various import restrictions and other hurdles detailed in this article. One has to step back and survey the automotive landscape in Europe in the 70s. It was a low point in a number of ways, especially in quality and reliability. The standards for durability and reliability had always been somewhat different in Europe than in the US, which explained why the more durable VW succeeded in the 50s and 60s in the US, and most other Europeans didn’t. Europeans drove much less than Americans, rarely commuted with them, and were willing to pamper their cars much more, as they were not so much seen as a daily necessary appliance but more of a luxury/convenience item used more typically for outings and vacation.

The late 60s and 70s were also a time when there were major labor issues all over Europe. The 60s unleashed a dissatisfaction with factory work, and morale dropped accordingly. This was felt more acutely in Great Britain, Italy and France than in Germany. It clearly impacted quality. As did the often overly complex designs of modern European cars at the time.

I had a continuous subscription to Auto, Motor und Sport (“AMS”) from my godfather from about 1970 until he died about 15 years ago. AMS is/was the dominant German-language magazine, and had affiliates in other countries. They were very powerful and influential. And very cozy with the German industry, which were of course their major advertisers.

They also were pioneers in long-term tests, which originally were 50,000 km, later 100,000km. It was fascinating to see how poorly some European cars fared in these tests. I wish I could find reprints, but the number of failures and visits to the dealers were sometimes amazing. Engines experiencing fatal failures, transmissions having to be replaced twice (a Renault), and many other mechanical and electrical failures of all kinds. Not surprisingly, Mercedes sedans, especially the diesels, generally did best. I’m not being biased when I say that French, Italian and British cars pretty consistently fared poorly, as well as some German cars too.

It was in this environment that the Japanese, with their reputation for reliability, should have done very well. But AMS consistently found things to downgrade Japanese cars in reviews and comparison tests. They did that by applying much more weight to extreme performance aspects than the qualities that were more relevant to a typical driver. And this despite the fact that German owners were constantly bemoaning the poor reliability of their cars in the magazine, in surveys and letters.

One example really stands out, but there were many others. The Lexus (Toyota) LS400 took the US by storm, undercutting the German premium sedans in price yet had unparalleled drivetrain refinement, comfort, ride quality, and overall quality. The LS made a huge impact on the Germans in the US, and they greatly feared it might have a similar effect in Europe.

So they found areas to attack the LS400. It was designed specifically to be a more comfortable riding luxury sedan than the rather stiff riding Germans, so its handling was claimed by AMS to be dangerously unstable at high speed, in maneuvers that no normal driver would undertake. And then they attacked the LS’ brakes. They set up extreme comparisons to make their point, including one on the Grossglockner mountain road, the highest in Europe. The test cars were repeatedly accelerated on the steep down grade, followed by full panic stops. Over and over. Who would ever drive like that, charging down a steep mountain road to repeatedly panic stop?

But yes, the brakes on the Lexus did not hold up quite as well as the Mercedes, BMW and Audi, and were deemed to be inferior and therefor unsafe. This was picked up by the German media and hyped. The whole thing was nothing more than a concerted smear campaign. And it worked: everyone now knew that the LS handled dangerously and had bad brakes. As if. It all played right into the tendency of Germans to crow about the superiority of their cars, regardless of how they were actually intended to be used.

Toyota was mortified, but quickly revised their suspension tuning for Europe and beefed up the brakes. They were shown to be comparable, but it got zero attention in the media. The damage was done. The LS never had a chance in Germany; that was highly predictable.

The German car industry is a colossus, and in concert with the press and media were out to do whatever it took to badmouth Japanese cars. The Lexus LS wasn’t the only one. Similar scenarios happened with others too. Let’s just say that the press was not exactly welcoming. But then chauvinism is not uncommon in the press in Europe; how many comparison tests in the British car mags were invariably won by domestic cars, as long as there were some?

That’s not to say the Japanese were the equals of the Germans and other European cars in every respect. The Europeans had a long and deep history of building small cars, and were technologically often advanced. The Japanese were more conservative at timese, and at times, although cars like the Honda Civic were as modern as any in Europe at the time. For discerning drivers and enthusiasts, the European cars were often a better bet. But for the more average driver, these were not issues, and the Japanese had their distinct advantages too.

Despite claims to the contrary, American car magazines actually were much better about putting various cars into the proper context. And the disparity of how Japanese cars are perceived in the US and Europe became mostly quite stark. The 2019 Honda Accord just got its 33rd year of inclusion on Car and Driver’s 10 Best list. Meanwhile, the Accord isn’t even available anymore in Europe. And its image there was invariably as a second-rate car. Who’s right? Are Americans besotten with Hondas, or are Europeans chauvinistic?

AMS was all about test stats and hard numbers, with a scale that tended invariably to favor German cars. Except reliability, of course. They couldn’t do anything about the much better than average durability of the Japanese on their long-term tests. It soon became an embarrassment. The difference was typically and often very acute.

There’s no way for me to dig up those test results, but I do have something roughly comparable: the annual ADAC ratings of their breakdown statistics. ADAC is the organization that responds to essentially every automotive Panne (breakdown) in Germany. And with the Germanic proclivity for thorough record keeping, they have kept them all, and analyzed them accordingly. I did a post on them here, which gives more information on their methodology.

No, they’re not necessarily 100% perfect, but they were accepted as being quite representative by the German industry. Any set of statistics that tends to replicate certain results (high rankings by Japanese and MB diesels; low rankings by French and Italian cars) as well as pass the common sense test is meaningful. Actually, these results were very influential in Germany in their day, although they have lost relevance in more recent years as manufacturers have learned to game the system and have their own roadside assistance programs as well as the improved reliability of modern cars.

Is it a sheer coincidence that France, who clearly built the most unreliable cars, also had the most extreme import restrictions, holding Japanese imports to 4% in the mid 90s as per the NYT article? Even today, the Japanese share in France is one of the lowest, at barely 10%. The term “chauvinism” does originate from France.

So how does high rankings by the Japanese explain the lack of more success in Europe? The Europeans were forced to drastically improve their quality and reliability in the face of the stark disparity with the Japanese. And although some/many/most Europeans undoubtedly still don’t have the stellar reliability of a Toyota, it improved to the point where it was no longer a major issue. Reasonably good was good enough.

As a response to the quality disparity, the Japanese did have a pretty strong early success in countries like Germany that didn’t throw up major import barriers. The Mazda 626 in the mid 80s sold quite well in Germany, as did a number of others. But the early momentum was difficult to maintain, the reason being that the European market increasingly diverged from the US or Japanese domestic market.

In Germany as well as in Great Britain and some other European nations, taxes favor fleet cars, where employees are given cars as part of their compensation. These are typically managers and executives, so the cars tend to be expensive and prestigious (junior and senior executive class cars). This helps explain the rise of the German premium brands all over Europe, especially so where taxes favor fleet company cars. But the Japanese have never cracked this fleet/business market to any meaningful extent. It wouldn’t look right, and the prestige isn’t there.

This also explains why German (and other European country) car sales stats are very misleading: if one takes out fleet sales, true retail sales tend to be mostly quite cheap and modest cars. Analyzing true retail sales one would find that the Japanese brands do much better than the overall numbers suggest. It also explains why Japanese brands have a low image, as in cars driven by the old and thrifty. That’s because they don’t get the tax breaks of company cars and their owners who buy them with their own money do tend to care more about costs and reliability.

The other factor is that the European market has been changing considerably in the past decade or so. It’s been diverging into a market that favors premium brands and ultra-cheap brands. The middle of the market has been hit very hard, which explains why Opel, Ford and some others are doing so poorly. Renault’s big success has been with Dacia, a budget brand. VW has Skoda. But the Japanese are also right in the middle that’s been getting hollowed out. The Koreans have done much better in the past couple of decades as they are seen as budget brands, although their prices are not that much lower anymore.

Environmental regulations are also a huge factor. Diesels are out, small high-efficiency gas engines, EVs and hybrids in. This is impacting everyone, and the smaller players disproportionately so.

These factors have also changed the kinds of vehicles that are in demand. Like elsewhere, larger sedans and wagons have been hit hard, except for the premium brands. CUVs and MPVs and very small cars are what the retail market is mostly buying. That explains why Honda dropped the Accord, and Toyota’s biggest passenger car in Germany is the Auris, which is really a Corolla under the skin.

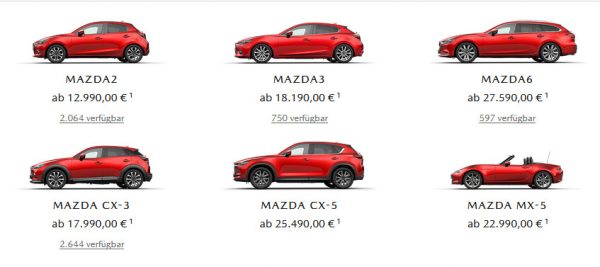

In NA, the Japanese have invested in numerous vehicles and platforms that are unique to the region. There’s not much overlap at all anymore with the Japanese domestic market, NA and EU. Each one requires unique models to be successful. This is putting huge pressure on the Japanese. Only Toyota is big enough to keep up quite well (4.9% market share in 2018), with a large palette of some 16 models that covers many segments in the market.Toyota’s hybrid technology is a big boost to them currently, as the market moves away from diesels. Almost all of their cars are now either hybrids, or available as hybrids.

Toyota also has Lexus, but it’s been a challenge to compete against the German premium brands. For instance, Lexus sold all of 5,400 cars in France in 2018.

Meanwhile, Honda is down to 0.9% share, and just four: Jazz (Fit), Civic, HR-V and CR-V. That explains why Honda is bailing on EU production and will harmonize its products from China with the EU. It’s a fall-back strategy, at best. Honda is too small to fully compete in Europe.

Nissan is doing better (3.2% share) because of their alliance with Renault, that gives them Europe-appropriate platforms as well as because they jumped into the CUV game early on in a big way. And they have commercial vehicles, as does Toyota, unlike Honda. Nissan also sells Infiniti.

Mazda is hanging in there, slightly better than Honda, with a 1.5% share.

Mitsubishi’s share is in a similar range. And Suzuki’s is even smaller.

Meanwhile Hyundai-Kia combined had a 6.7% market share. That’s a story in its own right.

I have not done this subject justice. It would require a book. Each European country has its own story to tell in terms of their ways of reacting to the feared Japanese Invasion. But the overarching one is that although the Japanese had an opening in terms of superiority in quality/durability/reliability at the time they arrived in Europe, their real or perceived dynamic shortcomings (such as they were) were amplified in the press and media. And as the NYT article details, there were and still are other barriers to the Japanese brands in Europe.

The reality is this: the Japanese may well fade from Europe, with the likely exception of Toyota, which has six plants and a joint venture.The European market is stagnant and in demographic decline. Mobility, autonomy, mass transit and other forms of transportation meanwhile are growing. The European market for private automobiles has seen its best days. This is why GM sold Opel, and why Ford is struggling mightily.

Meanwhile, there are much better opportunities in other parts of the world, in areas the Japanese have generally already done well. China has of course been a major growth opportunity in the past two decades. Now the very fast growing Southeast Asia area outside of China is at the top of the list. But South America, Africa and the Middle East are all high-growth markets. And the Japanese, especially Toyota, is very strong in all of them. Why kill yourself in a shrinking, complicated, highly-regulated market that has often created barriers of one kind or another? There’s more fertile opportunities elsewhere.

The key take-home point: The Europeans may have successfully fended off a Japanese invasion, but they have the Japanese to thank for much more reliable domestic cars.

I spent about three weeks in Europe in 1984, my first time there as an adult since the mid-60’s. I noticed more Japanese cars in Switzerland than anywhere else; at the time, I didn’t know about tariffs but also observed that some of the more popular vehicles in Swiss rural mountain areas seemed suitable for the market, with no real European competition then: specifically 4wd Subarus and Nissan and Toyota pickups.

My aunt gave me a 3 year subscription to the British weekly Autocar, from 1968-70. They treated Japanese cars as a novelty, and were generally critical of their handling, ride and performance. Yes, the Nissan Bluebird (510) was far inferior to an Austin Marina. But perhaps with the growing popularity of Japanese cars in former colonies like east Africa and Australia, they at least acknowledged that they were rugged. Crude, but rugged.

Looking at the Nissan lineup, the Qashqai (Rogue Sport), X-Trail (Rogue) and Pulsar look ripe for replacement with a single model with “high” and “low” suspension variants, with the “low” one also taking the Sentra’s place in their US line which has too many interchangeable sedans as it is.

In Great Britain, not that long ago, Nissan did indeed stop selling sedans with the Qashqui taking over for the Sentra.

Nissan has, I believe, 1 or 2 SUV/CUV? type vehicles it sells outside the US, but I don’t remember if the “big” Rogue is sold in other markets.

And yet, Nissan reversed that market strategy by introducing the Pulsar sedan…sort of Nissan’s competition for the Corolla.

One point to add with the executive company cars – surely it’s relatively cheaper to keep an aging Mercedes/BMW/Audi running in Germany than America, and all those off-lease company cars inevitably end up competing with new cars a class or two cheaper, further driving down demand.

Wow, Paul—what an education this was today . Answered a lot of questions for me, including several I wasn’t even aware enough of to ask. CC broadens my international perspective lots, thanks to meaty essays like this (and Comments from non-North-American CC-ers). Nice work!

I think another factor to be considered is the location of the US, relative to both Asia and Europe. US ports are easily accessed by direct surface travel from either continent. Ocean surface travel from Asia to Europe, on the other hand, necessarily involves transit through Panama or Suez, unless one takes one of the scenic routes around South America or South Africa. The economics of shipping cars from Japan to Europe in the 1960s and 70s likely played a major role until European labor and manufacturing costs caught up to the US.

I’ve never heard that given as a factor. It certainly doesn’t hold up since the Japanese weren’t priced higher; in fact lower, typically, back then.

The giant ships used for shipping things all over the world make shipping costs a very low percentage of the item’s total cost.

In general (not just automotive) ocean shipping is very cheap, but there is the cost of inventory being tied up on a “boat” for months. That is usually factored into pricing. I also don’t know if in the ‘70’s and ‘80’s it was common to order cars in Europe, whether because small urban dealers didn’t have inventory, or to get specific colors and options. That probably wasn’t feasible with Japanese cars … not necessarily a real issue, but something that could be used to sow FUD by the local manufacturers.

The Japanese did what they did in the US: they sold cars only nicely equipped, so buyers didn’t have to agonize over which options to be fleeced over. No strippers. And at better prices than a comparably equipped European car.

Great article Paul!

Perhaps because it comports with my views and experience.

My experience: Greece and Iceland had, and have LOTS of Asian cars because they don’t have a local auto industry. In Greece, prior to joining the Euro (which has proved to be toxic to Greece, but that’s another opinion for another day), struggled with a trade deficit. So the govt was not going to ‘help’ more expensive Euro cars priced in D-marks, francs, sterling, or lira vs. less expensive cars priced in yen. Less expensive cars mean smaller trade deficits. Prior to joining the EU, Greek taxes on engine displacement really hit cars over 2.0 liters, regardless of where they came from.

Switzerland….lots of Japanese cars.

But European carmakers enjoyed a stay of execution under the umbrella of barriers, OR, as you show, the sense of ‘patriotism’ in Germany.

America is an open society. Open market. Relatively easy for other countries who know how the trade game is played to eat out lunch. And they have. Of course, the greediness of US auto management first, and labor second, and lack of vision by the Federal Govt have not helped, giving everyone easy access to the world’s biggest richest market. Also, the US Fed Govt was more concerned with keeping our “allies” allies during the cold war, and if that meant that economically, they took advantage of us, so be it. The way the Japanese destroyed the US TV industry in the 1970s is a textbook case. By the time the govt found that, yes, the Japanese ‘dumped’ TVs into the US market, there was not longer a US TV industry to save. Result: high-tech flat screens are designed overseas, and many built overseas too. Reagan, a “conservative”, to his credit tried with the quotas. His 25% duty on big Japanese bikes also saved Harley Davidson (which shameless build bikes overseas now…)

So now we have potential tariffs. A little late, perhaps, and with the potential to cause much damage. BUT, it will hurt America’s trading partners a lot more than the US. I see tariffs in this case as LOSE vs LOSE MORE (US vs Europe).

Of course, we Americans have to have something of value to trade. When fuel cost $6 to $10 per gallon, US vehicles won’t be in high demand in Euroland. Still, why should our measly sales be taxed at 10% while their (Germany) megasales here are taxed at 2.5%? It’s a no-brainer to me…if I am King of the EU, I cut my duty on US products. No one buys them anyway. Perhaps I’m missing something…

Great job Paul, thanks!

Actually the US exports quite a lot of vehicles to Europe, just not with a Detroit badge: all Mercedes and BMW SUVs except the very smallest are built in the States. Conversely not nearly all German (badged) cars in the US are imported. BMW’s largest factory is in “Saus Käroleina” as Merkel reemphasised just this week.

Fascinating, Paul. Opens up some perspectives I’d never considered before.

And maybe it’s my age…but that 1968-ish Toyota print ad conveys more excitement than the “HEY LOOK AT US WE’RE FUN NOW!” image they’re trying to portray nowadays.

In North America the Japanese makers Toyota, Honda, Nissan and Subaru are gaining ground at the expense of US automakers, but its upscale bands are under attack from three Germans. They have a better lineups and finally figured out the best way to sell its products is to lease them out. American loves the prestigious bands and debts. Then they resell the off lease vehicles to the suckers.

Very interesting stuff. One factor that you kind of touched on is that when the Japanese got a start here it was in segments mostly ignored by American companies, so there was really no reason for US companies to get bent out of shape. European companies had those segments to themselves in the 50s but lost out to the Japanese that withstood American driving and maintenance conditions so much better.

But the Japanese cars competed directly in the heart of the European markets and were therefore a dire threat. Both industry and government mobilized to defend against those Asian interlopers to a far greater extent than happened here in the US.

Very interesting stuff. One factor that you kind of touched on is that when the Japanese got a start here it was in segments mostly ignored by American companies, so there was really no reason for US companies to get bent out of shape

That’s my take too. Asian levels of consumer discretionary income, fuel prices and tax policies resulted in products close enough to be competitive in the European manufacturer’s core markets. The European manufacturers immediately took notice and rang up their elected representatives. Probably didn’t hurt that, at that time, Renault was entirely state owned and VW still has significant government ownership, while British Leyland was hanging on the government teet.

But here in the land of cheap gas and big freeways, they were at the low fringe of the market. The operative meme in the big three management echo chambers has been “small cars equal small profits” at least since the day after Henry Ford died. I can just see HFII thundering “you only want to spend $1800 on a car? I’m not fighting for fiddling small change. Go away, and buy a used Fairlane”. So, when the Japanese showed up, the big three didn’t really defend that market segment, because they didn’t want it. The best the big three managed was importing some Cortinas and Kadettes, which would have been equally hurt by any protectionist trade regs that would have been aimed at the other imports.

By the time the big three got serious about, let’s call them “global” size cars, 50 cent/gallon, soon, $1/gallon gas was bringing the roof down around their ears. So the big three cried until the government moved. Rather than phasing in domestic content rules that would not have full effect for years, the big three wanted protection “now!” so got the import quotas.

What did the Japanese do to grow profits when they couldn’t grow volume? They moved upmarket, spawning Acura (1986), Infiniti (1989) and Lexus (1989), while making their core brand models larger, more luxurious, and more American. *Now* they were in the big three’s core market, but it was too late for the big three because their bleatings in DC were drowned out by the sound of well established Japanese companies building factories here that could not be pried out with domestic content legislation.

The first iteration of CAFE gave the big three an incentive to produce their own small cars as the reg used a sales weighted fleet average to measure compliance. Ford could build all the Crown Vics it wanted to, but it had to build enough Escorts to pull the average up to the CAFE mandate.

The big three had another bright idea: CAFE “reform”, in 2006. The entire system of measuring compliance was changed so automakers are no longer required to build small cars to offset the fuel consumption of larger cars. Additionally, the reg was intentionally skewed to favor trucks over cars and larger vehicles over smaller ones. I read the new reg when it was published. The excuse used to justify the built in bias was that smaller vehicles are supposedly inherently “less safe”, so the intent of the bias was to discourage the production of smaller vehicles. This would seem to be custom made to favor the big three as, a dozen years ago, they could be perceived as having a stronger market position in larger, more truckish, vehicles.

So far, the “reformed” CAFE plan is working as expected. The big three are dropping their sedans, which had become also rans behind the Japanese entries, while the big three dominate large pickups and large SUVs.

The big three are barely hanging on to leading positions in midsize SUVs, and the leading compact SUVs, are from the Japanese. Probably doens’t really upset the big three, because, “small cars equal small profits”.

In an echo of the big three strategy from the 60s, their strategy for entry level CUVs is to phone it in by importing models from Korea, Italy and India.

So, yes, the big three’s own hubris allowed the Japanese to become firmly established in the US, rather than meeting the Japanese at the beach.

Thanks for adding perspective to the differing dynamics of the EU automobile market, Paul. It really goes to show how tax policy and politics (heavily weighted in favor of local manufacturers) can greatly influence the shape of a market from one country versus another. I was aware of corporate leasing as an employee perk in the UK, but did not know that was a major factor influencing the car sales mix in other EU nations as well. Might the U.S. equivalent might be the tax laws favoring the purchase of heavy vehicles for business use that have juiced the sales of luxuriously equipped full-size pickups and SUVs to small business owners?

i remember riding in a new ls400 in 1984 and thinking it looks like a benz (especially the excellent interior) but it drives like an oldsmobile.

the 1979s – 1980s was the peak benz and bmw era. i don’t think the japanese were quite there yet on the high end.

an interesting test will be to see what hapoens with asian car sales in the uk after brexit. my prediction is that they will increase rapidly.

What I’m about to talk about has only a tenuous connection to the success or failure of Japanese automakers in Europe. We like to say “every car has a story.” I would also say “every picture has a story,” or at least significance to someone.

I am referring to the nice color picture above of a “typical” import dealer, circa 1960. I recognized it immediately, having grown up in Westport CT. David Hackett owned and operated his dealership for about 30 years. He was a true gearhead. The story of what he did afterwards is here: https://www.courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-xpm-1997-08-11-9708110184-story.html .

I think his success was a classic example of being in the right place at the right time. Westport was (and still is) a bedroom community for folks who work in New York City. Many of them, like my dad, worked in publishing and advertising in era captured in the picture. A lot of those folks were the “creative types” (you saw some in Mad Men) who liked something distinctive to drive. Westport had a lot of artists and photographers. LIFE photographers like George Silk were neighbors. I don’t know what George drove, but John Cuccio, an industrial designer, had a Ferrari 275 GTB daily driver that he would park out in front of his office. A little pricey, maybe, but it seemed pretty normal to us locals at the time.

Hackett’s was located adjacent to the railway station (note the power lines in the background). Half the people going to the station passed by his little store and the line-up out front. Once you bought your Austin/Renault/VW/Isetta you could drop it off for service in the morning before getting on the train, and pick it up in the evening on the return. I suspect a lot of the cars sold there got more regular maintenance (and they needed it!) than those sold at the the typical import dealer of the era.

Hackett sold just about every import brand at one time or another. My dad was into oddball cars and I remember going to Hackett’s often (probably to get something fixed). We bought my sister’s Triumph Herald, my grandmother’s Peugeot 403, and the family Datsun 510 wagon at Hackett’s. I’m sure there are others I can’t recall at the moment. I would regularly ride my bike down there after school to see what was new. I saw my first Lotus Europa at Hackett’s, just parked out there in the lot, where the Morris Minor is in the picture. I think Mr. Cuccio had his Ferrari serviced there.

The successful brands eventually opened their own stores. Westport got a nice new VW dealership not long after the picture was taken. 15 years later Datsun bought out the franchise and opened their place. I am only speculating, but I think David was just happy running his small business with its characterful cars and colorful customers. He was performing a traditional role in product distribution: helping a brand get a foothold in the market. He had fun doing that, even knowing that the “winners” would inevitably move on to do it themselves. Roughly 30 years after the picture was taken, he closed Hackett Imports. The game had changed, Westport had changed, and it was time to move on to the next phase of his life.

I had not thought about Hackett’s in a very long time. That picture brought back a flood of memories and the realization that small dealership actually had a pretty big influence on my life. Thanks for posting it, Paul.

That scene of the DS with all the guys under the hood, likely arguing amongst themselves while trying to impress La Femme. I was once (upon a time) a competitive bicyclist are rode in groups often during the week to get my miles in. About 10% (or less) of the groups were female, and yes some Girls can kick ass on a bike and push gears hard (few were road racers, but most were either triathletes or mountain bikers). Whenever any guy got a flat, there’d be one or two others who’d come around and ask if you needed help or offer a part or special tool if you didn’t have one. No big deal unless one was really slow at getting the flat done. However, whenever a femme in the group got a flat, at least 1/2 dozen guys, often more if the group is large, would quickly trip over themselves offering to fix it for her, and at least two or three will actually do it in a time that would be the envy of a NASCAR pit crew. Once I missed out on this scrum and went over to the unconcerned Girl who was watching three guys fixing a rear flat on her bike and asked her about getting all this help, and she smiled and said, “I’m a Girl, so long as I ride in a group, I’ll never have to change a tire again.” She knew how to change a tire (all good riders do), but she wasn’t going to pass up this comic chivalry. Smart Girl.

Reminds me of my days in the Presque Isle Bicycle Club back in the ’70’s. Yes, I raced, too, very unsuccessfully. And yes, no girl in the club ever had to change her own tire. Occasionally the competence of the helping males could be amusing.

I had it a little better, as I had a complete bicycle shop upstairs in the attic of my apartment. Certain club females would bring their bikes down Saturday evening for a tune, a bottle of wine, and stay the night. Up early Sunday morning for the weekly club ride.

Chivalry has it’s virtues. And it’s rewards.

The London Honda dealer that used to service my wife’s Accord when she worked over there sent her an email this week promoting the “new” Civic 4-door saloon as an Accord substitute !

Our Accord has been pretty good, but has been let-down by non-Japanese components – and of course by Japanese airbags…

Interesting article Paul, on a subject I know little about.

Saw the title and thought we were going to do some WW2 history for a moment.

Personal anecdotes, which our comments are required to have, is how my own deeply conservative Okie family was unashamedly buying VW and Renault in the late 50’s and early 60’s. Who’d a thunk rednecks would buy a Dauphine in 1960?

I have wondered at the limited success of the excellent Japanese cars in Europe. Seems it had little to do with the cars…

Brilliant article, Paul. I knew the Japanese had a much smaller presence in Europe and you’ve helped fill in the blanks with some key facts and statistics.

The LS400 smear campaign is loathsome. I grew up reading a lot of UK car magazines for many years and they always seemed critical of Japanese cars. Sure, something like a Toyota Camry or a Nissan Maxima QX was never going to enjoy much success there — too big, resale value too poor, handling often soft. But mid-size fare often got tagged with the “minicab” insult and compacts were never quite good enough. At least the Brits were appropriately flattering when a Japanese car was really good — I remember delightful Autocar reviews of the ’92 Camry, for example.

Good analysis, I remember reading British car mags in the late 80s/early 90s talking about the “gentleman’s agreement” restricting Japanese imports and also the effect of Nissan and Honda’s UK plants. At that time a lot of Japanese models were seen as pensioner’s cars, inexpensive, reliable and boring. Car did have good things to say about sporty Hondas and Mazdas and the Lexus LS400. Britain is probably a special case since the native auto industry collapsed in the early 2000s as Rover folded, Jaguar/Landrover was sold and Ford and GM closed plants.

Interestingly Japanese cars sold very well elsewhere in the Anglospere with large market share in Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

Most interesting stuff, Paul. I wonder if Euro markets were also distorted by govt directives to buy local, for everything from police cars to ministerial autos? In Australia, such policies were a huge internal prop to the industry for years. Once we started signing up to free trade agreements, there were requirements to drop such internal tariffs. When folks in govt jobs and industries could now choose their own at leasetime, they did not choose the locals. Indeed, with that distortion gone entirely, and sales reflecting actual private sales, the no. 1 and 2. cars are small and Japanese.

I do quibble slightly about the journalistic standards. There’s not the slightest doubt that everything Euro except (most) Mercedes was atrocious across the time mentioned, (the French actually just beaten out for unreliability by the Italians in the Oz experience). The Japanese were demonstrably better built, better consumer goods. There’s also no doubt that some chauvanism meant Frenchys won in France, Germans in Germany, etc – good front covers. However, the publications were always for the very small percentage of readers who were interested in cars, the enthusiasts, if you will. The CC mob. And it is simply the case that the Japanese alternatives were NOT as good to drive as the exploding Euros, in the ways that matter to enthusiasts. Steering, ride, handling, seating, windnoise subtleties of feel. Thus a smoky Renault LeBombe of 1975 WAS a still a better car when tested against even decent Japanese efforts of that year. It really wasn’t until the late ’80’s at least that their cars began to become comparable in this way. (One could say that their own chauvanism – Japan sees itself as quite seperate from the rest of the region – seemed to mean they would not listen to what local markets would tell them about how to better tune suspensions, or seats). And the local markets actually did vary in what is valued. The French had crappy roads, thus ride quality was important. The Germans, good roads and autobahns where upper-end go and stability was the thing. All had need for compactness in old cities, and all a real focus on low fuel use even when flogged. None knew what an automatic was for! Auto motor und Sport might have been different (I obviously can’t comment) but it’s a bit of a cliche to say that the press were/are brought off by/compliant with the industry, and wrote accordingly. To say so always overlooks that most of the folks on the ground are journalists, with an independent and inquiring mindset, and (then) from the old school of hard knocks at that. The industry was and is generally wary of the good ones, and across those times, did not have the vast and sophisticated PR departments of today with which to overwhelm a cheeky voice. I’d argue that by continuing to have a go at the Japanese for crap steering, poor seats, lack of high speed comfort, lack of cohesion in feel, they ultimately forced change for the better, which is why for quite some time there has been no point in buying a Euro brand as it will be just a less-well-made version of the equal Japanese competitor.

Fascinating stuff.

It’s sometimes forgotten that the folks on the ground doing the testing of cars are journalists, and from a pretty hard-bitten crew across the time mentioned. I’ve not the slightest doubt Euro cars were atrocious for a long time, and the Japanese alternatives much better consumer goods. But the publications were and are written for the very small proportion of enthusiasts, for whom things like steering, brake feel, ride control, seating, ergonomics, wind noise, high-speed response are important. And in all those respects, the eastern alternatives were not good enough, not until at least the early ’90’s. It was quite in order to criticise such failures, and choose the Euro, even as the latest Renault LeBombe detached itself around the journo testing it. There weren’t the gigantic PR departments to smother a cheeky voice then, and I’d argue the continual harping against the obvious Japanese shortcomings improved the Japanese breed immeasurably. They too had been chauvanistic, for years not changing underdamped weak-steering formulas or styling unwanted by Europeans. Sure, the Euros had to lift their game for quality, but the Japanese perhaps took too long improving desirability in response to justified criticisms. Thus, in the badge-snobby world of now, their long-term build superiority (still the case, btw) cannot redeem them.

I’d add that there’s clear favouritism driven by nationalism and editors’ need for good covers (“England Wins Again!”), but the underlying work is clean. Other wise, it’s a bit like saying all Fox News journos do Murdoch’s bidding: it just doesn’t work that way (and no, not remotely endorsing that mob!) Perhaps the Lexus brake story was indeed a hit job (it does smell like it) but the BM and Merc didn’t fail the test, and testing must always be done to the limits to be meaningful. Especially for enthusiasts, and perhaps especially in nutter-autobahn speedy Germany. Would it matter in US or low-speed Oz? Probably not. But an ability to handle tiny yet 60mph B-roads in England matters there in ways it does not in big ole France. Market demands do vary.

I am of the view that journalistic pressure has been a big factor in the excellence of the cars we have today, and the journalistic imperative has been mostly driven by the pursuit of that excellence.

On a vacation to Europe a few years ago I was puzzled over the lack of Japanese vehicles anywhere. Now I know why. Don’t think I ever saw an Accord or Camry and only a few Civics. Plenty of Fiats and even Skodas, but few Hondas and Toyotas. One thing that struck me was that the cars were small. I mean, really small. Probably because streets in the crowded old European cities are quite narrow and parking is at a premium. Quotas and tariffs are problems, but another factor may be that many of the Japanese bread and butter products just don’t fit the European market.

Worked in Munich in the early 1980s at a small freight forwarding office which had leased a series of VW/Audi company cars. I took over an Audi 80 (4000 in North America). When its lease was up, was told I could pick anything else comparable because they didn’t like local dealer’s attitude. One co-worker lived near the Mazda dealer quite a distance from the office. But the Mazda 626 hatchback was much better equipped than a similarly priced Audi, so I took one. Drove very well, more practical because of hatchback vs. trunk with no folding seats. However, despite adjustable lumbar and bolsters, seats gave me backache within an hour. The Audi’s much simpler seats suited me much better. Anyway, some Germans bought Japanese if they were unhappy with domestic dealers.

European market is different and I see these points as biggest obstacle for Japanese brand to succes overthere:

1. High end cars – prestige is not there for Lexus today, and you can forget it totally back in 90s. Imagine typical Cadillac buyer from 50/60s considering to buy Japanese brand at that time. And being catched naked with the weak brakes proved Lexus did not make their homework properly prior entering EU market.

2. Many buyer are still loyal to their local brands. In France especially, you hardly see any other then French brand on the road.

3. Spare parts costs for Japanese brands are sometimes ridiculous high compare to local brands.

4. Lack of diesel engine offerings across jap.brands. Keep in mind it was VW who ignite the love affair with diesels engines all over Europe. And there is one technical point you are missing. Its not only about the low fuel consumption, but the finally available respectable torque with reachable engine size. Europe in general is very restrictive for engines size over 2 liters, where banks apply very high insurance costs. That’s the reason majority of engines are within 2 liters displacement. Sometimes the power kw is also lowered in specification, to meet the optimal insurance window.

4. Interior quality and layout is different, in EU VW group is the leader in this aspect not comparable to Japanese. And keep in mind, you were (or still?) getting cheapenout cars in any aspect compare to its European sibling so you can not get use it as prime example.

5. You find the repair shop for EU brands on each corner, not so much for jap.brands.

6. European drivers drives less milage then in USA, so the possible quality issues might not appear during the first ownership period, keeping the brand loyalty.

In general, in my opinion the taxes restrictions had much smaller impact on the jap.brands success in Europe then you might think.

Lots of good points there Lukas.

As usual the article is top notch but I don´t think the power of the European media against Japanese cars was so determinant. After all car magazines are mainly read by enthusiasts. Most usual is, when Joe Public buys a car, he buys what he/she is used to: Fords and Opels and Renaults and Peugeots…

Of course, restriction to Japanese car sales in some markets was an huge factor. In my country, Spain, few Japanese cars were imported until the end of the ´90s because of small quotas, and they were relatively expensive compared with the European competition. But even after the quotas, the Japanese, somehow, didn´t catch here, I can´t explain exactly why, because most car European buyers want the same as Americans: something reliable and good value to commute from A to B.

Another interesting factors were the start of diesel fever in the ´90s, when the Japanese were caught off guard, often with outdated naturally aspirated engines while PSA/VAG offered very good turbo diesels and even direct injection; and the reputation of expensive parts and servicing for Japanese cars. Having owned a Nissan Primera and a Honda Prelude, I can confirm that parts weren´t cheap at all (although I didn´t need too many…), and aftermarket parts weren´t as available.

Great article. The German propaganda machine does not only go after the Japanese but anything that comes up as a threat. Example: when Dacia appeared as a genuine value offering, ADAC deliberately deflated the tyres on one side and tampered with the wheels in some way to produce a spectacular roll-over. At the moment it claims that Dacia is the most unreliable car in its class. All that this means is that Germans have no answer to the Dacia and view it as a true threat. Basically, if ADAC or AMS slam it, buy it. The propaganda failed with Dacia, not sure why, but it sure worked with the Japanese (see https://www.thelocal.de/20140120/adac-boss-cooks-car-award-votes for examples).

Noting the comment about tiny cars: the Japanese are excellent at small cars because of their own congestion. Honda Jazz, for example, is a Tardis. Daihatsu had a plethora of attractive superminis in the 80s and 90s. However, by then the “bad dynamics” (partly true) and the “poor safety” media attacks had already created a bad image and many Europeans, for some reason, still think that a VW Golf is a car of higher quality than the Toyota Corolla, which is simply ridiculous. German breakdowns are the same on the US side of the pond as on the Euro side, the difference is that Europeans fail to admit that this is an intrinsic failure.

I wonder what accounted for the Honda Civic to be rated the worst by ADAC in 1982 when there were supposedly few of them in Germany at the time…it’s the lone Japanese car in the worst category.

Like many others here in the US, I knew little about this subject. All I had any knowledge at all was the Honda-Rover joint venture that produced the Sterling. My boss had one. Also, that I believe Civics were locally produced in the UK, maybe from the same joint venture.

On my last trip to Europe (Sicily, not Germany) I was surprised at the number of Korean brands on the road, and a fair number of new Corollas.

Paul, these articles are gold. Thank you.

First allow me to thank Paul for this thorough post.

If you ask me, it was not just quotas and bad reports. Searching my memory I recall that all the way into the 90s, Japanese cars WERE a feature on the streets of many a European city. In fact, from what I remember, here in Austria (and also in the UK) Hondas and Toyotas were pretty visible. No, sales were nothing like those achieved by the usual European suspects but they were respectable alternatives. Then something happened and my feeling is that Japanese manufacturers turned their attention more and more to the US where they had huge sales. It was as if their heart was not in it anymore; the cars became duller and duller (all Toyotas), outlandish (Civic) or appealed to a very specialised sector (Subaru). At the same time – as noted above – the reliability of European cars has improved greatly. So today most Japanese cars (speaking again from the PoV of the Austrian market) are seen as worthy yet infinitely DULL, and that gives you bonus point mostly with the over 65s (a shrinking market segment) and nobody else. It is not a coincidence that Mazda – who produces the most “European” cars – is the best selling Japanese maker here (with Nissan who has a very diverse range second). And no Japanese maker sells as many as the Hyundai-Kia (which, as has been noted already, is another matter).

Well that’s my view at least…

Oh: in case anyone asks, I own a Mazda 3, so no Japanese car hater here. I do find the car offers a compromise between European-like road manners, price and reliability when compared with something like a VW (yes, the dealer treated me better than all the others I went to) and – when the time comes to replace it – it probably will be with another 3.

Fantastic piece, Paul. Thank you for your insights.

I keep impressing upon my kids how important it is to be multi-lingual, to help cut through the BS of the world. This article is a shining example of how being multi-lingual and multi-cultural allows for introspection, free-thinking, and having capacity for greater critical thought.

Thank you. Now this web site just needs a little Chinese/Japanese/Korean cross-over expressing more of the world views from the insides of their car cultures. Thank you for creating an interactive space with Brits, Aussies, South Americans, Israeli, New Zealanders, and yes, Canadians…