In the mid-1970s, about 60,000 US baby girls were named Jennifer each year – a staggering 4% of all girls. Parents flocked to the name for good reason – it was fresh, sophisticated-sounding, and (since it was nearly unheard-of just 20 years before), was seen as unique. But over time, the name Jennifer became a victim of its own ubiquity, its freshness diluted by overuse. Just a few decades later, the number of babies named Jennifer had diminished by 90 percent and was falling fast.

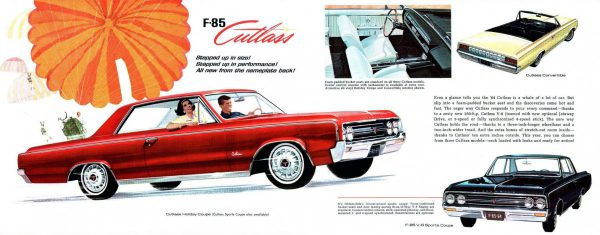

During the same period, an equally staggering 4% of US new car sales were Oldsmobile Cutlasses. Consumers flocked to the car for good reason – it was fresh, sophisticated-looking, and (with a new, formal design), was seen as unique. But over time, the Oldsmobile brand became a victim of its own ubiquity, its appeal diluted by mismanagement. Just a few decades later, Oldsmobile had rolled out its last car.

Is this a coincidence? Yes, of course… but it’s an interesting coincidence. Both are reflections of people’s choices and aspirations in 1970s, and if this white Cutlass needed a name, I’d call it Jennifer.

The mid-’70s Cutlass was somewhat of an accidental phenomenon. Upon its introduction, few would have guessed it would become the most popular car in the United States, even outselling its Chevrolet cousin. While the seeds of this popularity were planted with earlier Cutlasses and by good product planning, much of its success is attributable to plain good luck – this car was in the right place at the right time.

Cutlass debuted for 1961 as Oldsmobile’s compact, then in 1964 the name was shifted to Oldsmobile’s entry into the then-nascent “intermediate” market – a segment that would soon dominate showrooms from all Big Three manufacturers.

An all-new car for 1968, the third-generation Cutlass (and other GM A-bodies) reflected its era, with a swoopy, fastback-inspired appearance. Intermediates developed into the auto market’s sweet spot, and consumers developed a fondness for luxury-type features ordinarily associated with full-size cars. Offering a taste of luxury on a mid-size car with a mid-range price turned out to be Oldsmobile’s specialty. And for Cutlass’s next generation, the timing couldn’t have been better.

The fourth generation Cutlass was introduced for 1973, by which time intermediate cars comprised North America’s largest-selling segment. GM called its new intermediates “Colonnades” due to their pillared – rather than genuine hardtop – roofs, and they featured contemporary designs that captured consumers’ desire for something fresh.

GM made significant styling changes for the Colonnades. Notably, not one of their intermediates featured a proper hardtop (likely in anticipation of government rollover standards). This was somewhat controversial at the time, and one Ford executive predicted that “GM will get clobbered if they drop the hardtop.” He was quite wrong.

Colonnades also reverted to more conventional notchback styling, turning their backs on the previous decade’s fastback trend. While Base and Cutlass S coupes still featured a quasi-fastback design, the upmarket Supreme featured a true notchback appearance. Guess which was the better seller? By far it was the notchback Cutlass Supreme.

Cutlass Supreme’s success pointed to the future – customers were tiring of fastbacks and the remaining vestiges of 1960s sportiness. The Supreme, with its formal notchback, scalloped creases emanating from the wheel wells, and opera windows, was seen as forward progress. At a time when the Brougham blossom was already blooming and intermediates consumed an ever-increasing market share, Olds hit the nail on the head with this subtly broughamy intermediate.

Ironically, Olds officials were caught somewhat off guard by the Cutlass Colonnade’s success. In late summer 1972, Oldsmobile General Manager Howard Kehrl sanguinely forecasted an 8.6% increase for 1973 total division sales, based largely on anticipated sales of the compact Omega. Instead, total division sales increased by 21%, thanks instead to the Cutlass.

Source: Standard Catalog of Oldsmobile, 1897-1997. Includes RWD Cutlass models, including Cutlass Supreme, Salon, Cruiser wagon and 442.

The Cutlass Colonnade and its 381,000 first-year sales was no one-year wonder. After dipping for the recession-tainted years of 1974 and ’75, Cutlass sales skyrocketed for its 4th and 5th model years, peaking at 632,000 units for 1977. Olds propelled to America’s third best-selling make (overtaking Plymouth), and for several years Cutlass was the nation’s #1 nameplate.

Seventy-nine percent of those 1973-77 Cutlasses were 2-doors, and 74% of those 2-doors were Cutlass Supremes – so our featured car is a perfect example through which to examine the Cutlass Colonnade phenomenon.

A whole book could be written on the Cutlass and its many variants, which were produced in coupes, sedans and wagons, all in a vast array of trim levels. Entry-level Cutlasses marketed as bargain or fleet specials cost about two-thirds that of a fully-loaded Supreme, advertised as Oldsmobile’s “little limousine.”

Offering one model with such a large price differential was a curious strategy, and somehow it didn’t turn off higher-end buyers. Oldsmobile’s Marketing Director opined that this somewhat unconventional approach was key to the Cutlass Colonnade’s success. “Can it be,” said James Bostic in 1978, “that Oldsmobile has abandoned the industry’s traditional mass market approach to pursue a strategy of market segmentation within the Cutlass line?” Whether knowingly or not, Bostic foretold the future. Following up on the Colonnade’s success, Olds tried to be all things to all buyers, and on top that, the Cutlass name was slapped on just about every vehicle imaginable. While this market segmentation exercise produced near-euphoric results in the mid-1970s, it eventually led to a dilution that killed the brand’s image.

One of the more intriguing Colonnade variants was the Cutlass Salon, marketed as a touring car with a handling package and “European trim.” Salon’s main feature was the anti-roll bar equipped handling package, and although calling this car European was a stretch, it did offer a reasonably responsive ride for its day. Even the standard Colonnades handled better than their predecessors, as Olds put considerable effort into improving the Cutlass’s drivability. Still, Salons didn’t exactly fly off of dealers’ lots — they accounted for about 10% of total Cutlass Colonnade production.

But enough of market strategy, let’s look at this car itself. As with other Colonnades, the 1973 redesign provided a clean profile, as well as a clean break with the past. This was considered a modern design, and GM reaped the rewards for accurately gauging customers’ preferences. Two (instead of four) round headlights visually amplified the voluptuous fenders, and combined with the unique side sculpting, provided a distinctive, if somewhat extravagant, image that was perfectly suited to an mass-market Oldsmobile.

In an era when long, low and wide cars were appreciated, design details visually augmented these dimensions. The lack of vent windows, for instance, created a long expanse of side glass that drew out the car’s length, matching the (unnecessarily) long hood. Other small features further augmented the design themes, such as the frameless side windows and “lift-bar” door handles.

In the rear, protruding vertical tail lights duplicated the prominent headlights’ visual effect (this particular tail light design was used only for ’75, but others were similar). Olds also used the new tactic of inserting plastic fillers between the bumper and the car, giving the extended bumpers a more integrated appearance.

Bumpers, in fact, were one of this car’s more significant innovations. The front bumpers were mounted on a shock absorber system, consisting of retractable hydraulic cylinders. Further, the grille was hinged at the bottom to retract with the bumper during minor collisions. This all added 60 lbs. to the car’s weight, but met federal bumper standards more elegantly than most cars of its day.

Inside, Colonnades debuted a completely redesigned interior, with a cockpit-style dashboard featuring two prominent gauges set in deep housings, complemented by swiveling round vents on the passenger side. Front seat accommodations were comfortable and roomy – the rear, however, offered a surprising lack of room for a car of this size (the sedan, riding on a 4” longer wheelbase, was more spacious back there). Such a shortcoming hardly hurt sales, however, even though the Cutlass was marketed heavily to families and others with the need to carry passengers.

The most notable interior feature of this particular Cutlass is the front seats, which reveal two rather short-lived attributes: the seats swiveled and they featured reversible cushions.

Though swiveling seats weren’t a new concept (Chrysler marketed them in the late 1950s), GM’s application in certain Colonnade coupes marked the highest production volume the concept ever attained. Meant to ease ingress and egress into both the front and rear, these seats could swivel 90°, and in some respects, did make access easier. The concept – though a relatively popular option – didn’t outlive the Colonnades, perhaps because the added complexity caused hassles, or perhaps because these one-piece seats didn’t recline.

Reversible cushions were even more short-lived, being an only-for-’75 feature. Vinyl on one side and velour on the other was supposed to give drivers the best of both worlds, but it was probably a better idea in concept than in execution – just imagine the kind of detritus that gets caught in the depths of a car seat!

The above ad shows a Cutlass performing all of its seat-swiveling and fabric-reversing tricks.

When the Cutlass Colonnades first debuted, available engines included two V-8s (350 or 455 cu. in.). However, in response to global fuel worries and an uncertain economy, for 1975 Olds added a standard 250-cid (Chevrolet-sourced) six-cylinder engine, as well as what it called a “baby V-8,” at 260-cid. Producing only 110 hp, this was certainly no rocket, but even the larger V-8s (170-hp for the 350 and 190-hp for the 455) had vastly reduced power from earlier years.

From a modern perspective, the Cutlass Colonnade’s sales success may seem illogical – after all, it broke no new ground, had only marginally acceptable performance, and a somewhat cramped interior. So what was the appeal? A summary of its appeal can be found within a period Car and Driver Cutlass test:

“…smoking tires and fire-breathing engines are gone, but now we have real bucket seats, rays of sunshine through a crush-resistant roof, and big car comfort… It seems that the Feds couldn’t squelch innovative thinking at Oldsmobile.”

At the Malaise Era’s dawn, even the hint of novelty was cause for celebration, and a quantitatively ordinary product could easily capture the public’s imagination.

The public’s imagination was definitely captured. 1975, our featured car’s year, was a jubilant time for Oldsmobile, which achieved an 8.6% US market share. In what seems like deja vu, in late 1975, Oldsmobile executives made yet another bullish prediction for the next year’s sales – which again turned out to be overly conservative. This time, newly appointed General Manager Robert Cook predicted already-hot Cutlass sales to increase by another 20% for 1976, citing “a solid basis of economic indicators.” In reality, sales of the mildly facelifted Cutlass increased by 51%, and then for one more trick, the Cutlass Colonnade posted its best-ever sales for its final year of 1977 – with over 600,000 sales. Cook later noted that “Cutlass came on like a tiger.”

A more analytical outtake was provided in 1977 by Oldsmobile Assistant General Sales Manager John Fleming, who noted that “An awful lot of people have moved down in size, from the traditional family-size big Ford and Chevrolet to intermediates. They found they could buy an Oldsmobile for not much more than the Ford or Chevrolet.” He was right. With its solid value and the enticing cachet of the Olds nameplate, Cutlass was the perfect car to succeed in its era.

For 1978, Cutlass was redesigned along with other GM intermediates, though Olds kept to its tried-and-true formula of providing big-car amenities with an intermediate size and price tag. For a few years, it seemed as if Cutlass’s success would continue indefinitely, but by the early 1980s, the concept grew stale. This 5th generation Cutlass stuck around for a decade, which was probably twice as long as it should have. But more importantly, the Oldsmobile brand had grown stale as well. Its cars were no longer fresh, sophisticated-looking, or unique, and consumers moved on to new concepts.

So it is that our featured car, nicknamed Jennifer, can be both phenomenal and mundane. Few other cars achieved such rapid success on the sales floor, and maybe because of that success, the Cutlass Supreme lost the sparkle that helped it succeed in the first place. A similar set of circumstances befell the name Jennifer once the 1970s ended… the name just lost that unquantifiable sparkle that attracted parents in the first place – a victim of its own success. And since car designs and baby names both reflect expressions of people’s personalities, it’s hardly surprising that such fashions would crest and fall similarly. For a short while though, both Jennifers and Cutlasses represented trends that sizzled with excitement and optimism.

It makes one wonder, though: 40 years from now, will someone write an article associating Toyota RAV4s and baby girls named Olivia?

Photographed in Fairfax, Virginia in April 2018.

Related Reading:

1976 Cutlass Colonnade Coupe: Expletive Deleted Paul N

1975 Cutlass Supreme Colonnade Sedan: The 216″ Long Surprise Paul N

Cutlass Supreme And Brougham Coupes: Absolute Supremacy Paul N

1976 Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme Brougham: The Right Car At The Right Time Tom Klockau

1977 Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme Brougham: Finest Brougham In All Of Hampton, IL! Tom Klockau

Outstanding piece, Eric. As someone who had sometimes been in a classroom with sometimes up to three or four Jennifers (born mid-’70s), you picked the perfect metaphor. Yours was a wonderful, welcome, well-researched new take on a car that’s been covered here before. Bravo.

Thirty years from now what CUV will we associate with girls named McKenzie (MacKenzie, Mekenzie, Mykenzie, Mikenzie, Makenzie – all versions I see as a high school teacher)?

“It makes one wonder, though: 40 years from now, will someone write an article associating Toyota RAV4s and baby girls named Olivia?”

Baby boys named Aidan seems more memetic.

Was going to say, none of the Jennifers I know currently drive anything with fewer than five doors or under five feet overall height. One has a Sienna, the others all drive CUVs. Even if they may have started out with one of the newer G-body Cutlasses as a hand-me-down (although by the mid ’80s most parents had moved on from the coupe-as-family-car thing),

I have 4 sisters. One of them named ALL her kids names that began with the letter “J” . One daughter is a Jennifer, she is single but in a relationship….or so I seem to remember, and while she has driven cars with 4 doors nearly her whole life, I believe she would rather have an SUV/CUV than the near new Corolla she bought when her Focus became nearly undriveable thanks to Ford’s crummy automatic transmission in the current generation of Focus.

I’m not really in the market for a car at the moment but every so often am tempted by a manual late model Focus. Since they calculate “book value” for a manual car by taking a standard deduction from the auto version, you’re getting a car with a troubleprone major component factored into its’ resale value, without that troublesome component.

Of course, that means the people who bought them are hanging on to them…

As the keeper of the masculine “J” name that was so stinking prevalent in the 1970s, your comparison is painfully apt. Bravo! In fact, there was even a book poking fun at it, see below.

These Cutlass Supremes were the car that emphasized the point of how a particular make or model can be everywhere and then are all gone in seemingly no time. I’ve always liked the ’75 due to its relative uniqueness to the ’76 – ’77 models and without the bug-eyed look of the ’73 models.

Incidentally, I was once friends with someone who had married a Jennifer. They soon divorced and he quickly married another woman – also named Jennifer. Perhaps it helped ease the transition to a new gal?

” Perhaps it helped ease the transition to a new gal?”

Or perhaps he knew he was prone to talk in his sleep. 🙂

As a matter of taste, I will never understand why folks buy cars where the body of the car and the vinyl roof are the same exact color, like the featured car. The brochure picture shows an attractive light blue car with a darker blue roof. Even nowadays, I see nearly new Camrys and Corollas here in northern Florida with vinyl roofs the same color as the rest of the car. To me, this only looks classy when the car is black.

As far as these Cutlasses, my boss owned a 79 or 80 that I drove once. It was a fairly pleasant car, not outstanding in any way. Yes, a true Jennifer car.

For better or worse, the difference in texture and sheen breaks up the shape and visually lengthens the lower part. If the roof styling is awkward or boring, the top “hides” it from the rest of the car.

My family got in on the ground floor of the Cutlass phenomenon and rode it nearly to the peak. From the 61 (F-85) through the 64, 68, 72 and finally a 74, I practically grew up in the things.

The 68 and 74 (both 2 doors) were my step mom’s. My mother went to replace her 2 door 72 Cutlass Supreme with a 4 door in 74 but started too late and her dealer could not get his hands on one for love or money. Instead of going with an 88 (too big) she bought a Luxury LeMans, thus going from one of the most common cars in the country to one of the least. I think I have had more Cutlasses in my life than Jennifers. 🙂

The notchback Cutlass Supreme 2 door actually went back to 1970 and augmented the normal fastback 2 door. The Colonnade style also gave a choice of coupe rooflines, with less slope on the fastback but more slope on the notchback.

The subject car is close to my step mom’s 74, except that hers had a blue vinyl roof and blue dash/carpet to go with the white in and out. It was a really sharp car in its day.

Thanks, Eric, for the good memories you have pulled to the surface today.

Also, it just now occurs to me that each of GM’s four Divisions that offered an A body in 1973 gave it the big dual headlights instead of the more normal quads. This was actually pretty unusual for that time in which quad headlights were almost universal on everything above the compact class. It makes me realize that Chrysler was a lot less bold and daring with the front of the ’75 Cordoba than I had been giving them credit for.

The use of dual headlights on the 1973 GM intermediates was quite noticeable at the time. The overall design of these cars made the styling touch seem upscale (perhaps high-line European?).

It was a stylistic continuation of the 1971 Camaro/Firebird look (and the Vega) that emphasized the front fenders with a strong, tubular shape that started (or ended) with that single headlight.

The 1970 Monte Carlo was the first intermediate to revert to single headlights, but these were not located in that prominent position on the end of the fender. There’s no doubt that Mitchell thought that the quad headlight fad had run its course.

The Camaro and Vega front ends were of course heavily inspired by Italian cars, most specifically the front end of the Fiat 124 coupe, which had very prominent headlights/fenders like that. But of course this was all just a continuation of the classic Pininfarina/Ferrari look going back to Farina’s 1946 Cisitalia.

The next GM styling fad would of course be the small quad rectangular headlights. Gotta’ keep throwing something new at the buyers.

The 70 Monte Carlo was first with single lights. GP got single lights and a boattail deck for 71, presumably to mimic some hallmarks of the planned 72 colonnade GP.

Oops; you’re right of course about the GP. The MC was the pioneer.

“This 5th generation Cutlass stuck around for a decade, which was probably twice as long as it should have.”

I’m glad it did. As a kid of the late ’80s and early ’90s, I was captivated by the G-Body Cutlass Supreme. There was something sophisticated, yet rebellious about the car that was part luxury car, part muscle car, and defiantly angular in a world where everyone was quickly trying to copy the 1986 Taurus (except Chrysler, but K-derivatives were decidedly NOT cool). It was available with T-tops! Ultimate cool.

I am definitely in agreement with you on this one. In the late 80s, when I would visit my grandmother in North Carolina during the summer, she and i would hang out on the front porch swing during the late afternoon. Everyday around 5:30, I could hear it before I saw it. A deep rumble of a V8 from around the curve on the wooded rural road she lived on. It would come into view, a white 2-door G-body Cutlass Supreme. It was decked out with all the chrome trim, white vinyl top, and the T-top roof. I don’t think I ever saw it with the T-tops installed. It had white SSII wheels and white letter tires. I thought that car was the bomb, very sweet looking and sounding. It’s because of this that the Cutlass Supreme is my favorite of the G-body cars.

I looked just like this, except with body colored wheels.

Yes, G-bodies were as popular as used cars as they were new. Many young guys in the 1980s thought they were cool – a bit behind Firebirds and Camaros, but with the benefit of being cheaper and more practical. That was the hierarchy at my high school c. 1986. The third place alternative was a 1960s car – a Duster or Barracuda or something like that, but that marked you as a motorhead (kinda cool but a less classy niche thing) and meant that you spent more time fixing your old heap than driving it. Below that were hand-me downs from your parents and random oddballs, in other words, mere transportation without any bragging rights. My car was a ’79 Monte Carlo, but in those days I could have just as easily ended up with a Cutlass.

Nice article. GM had finally returned to its original principle after a decade of Disruptive Innovation that failed spectacularly. (Corvair, Tempest, Vega). The Cutlass gave people what they wanted, and made them want more of it.

I still see ’70s Cutlasses every day, and I hardly notice them.

So far I’ve never seen one Tesla. Not one.

Disruptive Innovation is fun for the executives who have the Bright Ideas, but giving people what they want keeps the company alive.

Living and working near New York City, my experience is quite the opposite of yours. I see Teslas everyday, and I hardly notice them, but I have not seen a colonnade Cutlass in at least a decade. In fact, seeing any Cutlass (include Cutlass Ciera) around here lately is a rare thing!

And a related point is that these cars were quite well designed and built. In an era where lots of American cars had lots of things wrong with them, the Cutlass was sort of a throwback to “old GM” of the 50s. They could be faulted for some cheap trim details but on the whole they were good cars that did not cause their owners too many problems. I am sure that there will be the occasional person who will remember an awful lemon of a Cutlass from the 70s, but those stories are few.

I am guessing the Cutlass did not get stuck with the Turbo-Shitmatic THM-200 transmissions like the 78-88 models did in their early years?

What is your point? That GM should start building Olds Colonnade Cutlasses again?

As to giving people what they want, Tesla has about 500,000 reservation deposits of $1000 each for the Model 3. No Cutlass ever quite pulled that trick.

So you live in a junkyard? 🙂

Teslas are everywhere in the MD/DC/VA area. Columbia MD (where I was born and raised and still live) seems to be ground zero for them as they are everywhere. (Of course on a related note, nearby Bowie MD is ground zero for perhaps most of the Mitsubishi iMEVs out there. )

I see a very few Teslas in Central Maine, tourists mostly.

I believe some of the fully loaded Cutlass Supreme have air bag installed, a safety feature ahead of its time. I recalled in mi 80s some of them actually still worked at the accident, and some of the 2nd hand owners were not aware thier cars could do this.

The airbags were piloted in a fleet of 1973 full size Chevys. In 74–76, airbags were RPO for Olds 88/98, Toronado, Electra, Riviera, and most Cads.

I’m not a big fan of GM colonnades but the Cutlass coupes and the Grand Prix are the best of the bunch. I particularly like the 1976 Cutlass facelift with the smoothed-down sides and rectangular headlights. Fairly tidy-looking for the malaise-brougham era. Shame the bumpers were still too big.

To me, that’s the ultimate colonnade Cutlass. Just add T-tops and a white interior, please.

I remember when these rectangular headlights marked a car as “modern”. Older models with round headlights – or, god forbid, quads – appeared very old-fashioned by the 1980s.

Well, this one evokes lots of mental mumbo-jumbo for me this morning.

Firstly, I love this car. Its condition not-withstanding, the ’75 Cutlass Supreme remains forever in a neck-and-neck tie with the ’77 Grand Prix for my favorite Collonade. For some reason I never loved the waterfall grille the CS got later, but I inexplicably loved the front end treatment on the ’77 GP, which was not so different in many respects.

As for Jennifers, I dated one for a year or so in my late teens. Being that my first name is Michael, it was decidedly un-ironic that this pairing should have occurred, considering that Michael was the most popular boy’s name for many moons as well. In a similar vein, my current partner of 9 years is also named Michael. Ironic or not, this can get a little confusing at times. Please, nobody suggest that one of us call ourselves Jennifer. That ship sailed with the demise of the Cutlass Supreme.

The ’77 Grand Prix is my favorite colonnade too,

These must have been good cars, They took up permanent residence in the recommended used cars list of CR during the last half of the 70s. While Torinos and Polaras and visibly abused Camaros were plentiful and always there at the buy-here, pay-here lots that my folks inevitably sourced their daily driving beater/money pit from, the occasional Cutlass was rare.

Cutlass trade-ins went straight to the dealer’s used lot and sold fast. Chryslers hung around for a few weeks, then went to auction.

My parents were Oldsmobile loyalists at this time. When it was time to buy a another car, they actively searched for 1-2-year-old Oldsmobiles (although, in their case, a Delta 88).

Ralphie’s dad’s automotive preferences would’ve worked just as well if that movie had had a contemporary 1983 setting.

I hate the door treatment on the early 3rd gen Cutlass. It always made it look like it had been in an accident and got the doors dented. The 1976 refresh made the car look so much better

I used to dislike that door treatment too, but I find it’s grown on me – forty-something years later! At least all the GM colonnade cars had distinct sheetmetal, they weren’t just rebadged clones. After the refresh, the Cutlass looked lots more generic, and I felt the square front was at odds with the still curvy body – like a square peg in a round hole. Modern, but awkward…

“From a modern perspective, the Cutlass Colonnade’s sales success may seem illogical – after all, it broke no new ground, had only marginally acceptable performance, and a somewhat cramped interior. So what was the appeal? ”

I grew up with these cars. Oldsmobile for a very long time was the then equivalent of a Lexus; solid, reliable, comfortable, performed well compared with the competition, and aspirational enough to move people up from a Chevrolet or Ford while not being stratospherically priced. The dealer experience, like Lexus, was typically MUCH better than at Chevrolet or Ford.

Let’s compare with the Torino recently featured. The Cutlass had infinitely better styling and although not as roomy as it should have been for its size, still roomier than any of the competition. It was a reasonable size and more attractive to women than the dreadnought class full sizers. The two door style was considered sporty, less maiden aunt, old folks going to Piccadilly, while having a reasonably sized back seat for the 2.2 younguns and without four doors, less likely that the kids could open the doors and fall out. The Cutlass was more reliable, better built, with the right option packages had a more attractive interior, didn’t rust as much, and GM made the best V8s, best air conditioning, best transmissions, and didn’t rattle as much as the Ford or Chrysler products. If you bought a Cutlass, you’d be certain it would outlast the payment book and it would be more pleasurable to drive compared with the competition and you’d get a decent value for it come trade in time.

Compared with what else was in GM showrooms, and at this time GM had nearly 50% of the market, so it WAS the market, and competition was more interdivisional than anything else, the Cutlass won. The dealer experience was better than at Chevrolet or Pontiac on average, and Buicks were already a little Fuddy Duddy. The Nova platform was not much less expensive but the car felt a lot cheaper, and the 88s and 98s were considerably more expensive and “too big” for a lot of people.

The Cutlass had slightly better than average power for its day, a quiet, comfortable ride, handled better than the competition, generally optioned the way most people wanted them, and was perfect for the sort of long distance highway cruising that Americans do.

Oldsmobile was sporty then and had, like Lexus, a broad appeal. You could as easily see a 20something recently married family in the suburbs driving a Cutlass as Grandma going to church.

It’s a shame GM killed Oldsmobile. In the last year before the announcement, Olds sold around 265,000 cars and that was well after fleet fodder like the Ciera and Achieva had been killed. I always preferred Oldsmobile to Buick, as the mid 90’s LeSabres we looked at were way too fuddy duddy and squishy while the 88 was both roomy and athletic. 265,000 is a long way from Olds’ peak but it hadn’t really failed to sell cars. The Intrigue, Aurora, Alero, and 88 LSS were really nice cars. The Intrigue was certainly the nicest of the 2nd Gen W bodies and if GM had gotten its quality together, then owner experiences with the Intrigue and Aurora would have been vastly different. However, in today’s crossover market, it’s hard to see how Oldsmobile, a purveyor of somewhat sporty, refined, aspirational sedans would have survived. Perhaps rather than have it turned into a channel for peculiarly styled Korean knockoff Lexus crossovers, it’s better that our memories are great.

I think you are spot-on. Especially by 1973-75, Chrysler had developed a reputation for terrible quality and cheap-feeling bodies/interiors. Ford had developed a reputation as rusters that had more things break than they should, even though they showed pretty well in the showroom at the time. The Olds Cutlass pulled together equal parts of style, image, quality, features and price. Anyone that can put those things together has a winner. Chevy and Pontiac did it in the 60s and Honda/Toyota/Datsun did it in the 80s.

My parents drove Oldsmobile Delta 88s. The Ford and Chrysler offerings hardly registered with them…if they had contemplated a switch, it most likely would have been to the offerings of another GM division (most likely Buick).

Hard to believe today, but that was the level of dominance that GM had in some quarters during that era.

Savage ATL,

While you make many good points relating the success of the Oldsmobile Cutlass in the mid 1970’s, I do take issue with one comment. The Cutlass was no more roomy than any of its competitors. They all were decent in the front and small in the back, and I will post the measured dimensions below. No doubt the Cutlass was smaller than some of its competitors on the exterior which made it more space efficient, but it certainly was not more roomy by any measure of significance.

To quote Popular Science, my source for the below data, here’s what they said about the PLC’s of 1976 “Big on comfort and quite ride, these cars offer the front-seat riders plenty of room. Rear seat passengers, however, must have very short legs – or resign themselves to restricted leg room.

And here is how PS rated them in a nutshell.

Interesting point about late ’90s Oldsmobile. I always thought the B-O-P cars of that era were styled as Oldsmobiles first, and then messed up with anachronistic chrome and whitewalls (Buick) or spoilers and cheesegrater wheels (Pontiac).

The ’75 Cutlass was my county-supplied driver’s ed car in 1977 in bronze though I think it was a Cutlass S–did those come with an optional vinyl roof? (Many years later Mr. Green, my hs chemistry teacher and later my DE instructor, claimed that it was a Pontiac, but the fender side treatments I distinctly remember and wouldn’t have mistaken it for a Grand Prix. The DE car also had those classic Olds rally wheels.) It was luxurious compared to what I was driving at home (’65 Dodge Dart) and fresher than my deceased grandmother’s ’69 Old Ninety-Eight which we had at the time. But what I really enjoyed were the pictures of the ’64 Cutlass which my grandfather had (light blue, bucket seats and a console shifter), and the ’68 Cutlass my dad had with those very wheels and matched the body color. (Later, Mom’s dad also had a ’68 Cutlass, but it was bone stock–dad’s Cutlass S looked more snazzy in large part because of the classic rally wheels, but it was definitely not a 442.) The DE car I remember still had some kick to it, but Mr. Green frowned heavily on quick starts and sudden stops so I had to refrain from checking this. I haven’t seen any of these era Olds in a long time.

Navy Brat, we had Oldsmobiles in DeKalb County Georgia as Driver’s Ed cars and I too had a Mr. Green as Chemistry teacher at Shamrock in 1992. Could they be one and the same?

He is. Mr. Green is still frequently seen at Shamrock functions. You can find at least two facebook pages for Shamrock alumni.

Wow! Small World!

So many forget that not all Cutlasses were Supreme coupes. There were Cutlass Supreme sedans, which were an afterthought during PLC mania, and wagons too.

And forgotten are the base, S, and Salon trims.

The picture of the two rooflines shows the difference between regular A body and ‘A Special’. There wasn’t a G designation this era.

And yeah, many Baby Boomers in the 70’s bought Cutlasses, but then moved on to Cam-cords in 80s/90s [or SUV’s]

GM pulling divisional autonomy started the death of Olds. They became just another ‘GM rental car’. Aurora and Intrigue were too little, too late. Alero would have been better as a Chevy Malibu. Rebadged vans, SUV’s and CUV’s don’t have the same style as previous car lines.

GM starting in the Roger Smith era seemed to have the mindset that no investment was too huge as long as it would scale, and the inverse quickly followed as a bullheaded unwillingness to put in the cost-per-unit to make a car of the midprice makes *feel* like A Nice Car. That was particularly ill-timed given the extent Ford stepped up their game with the first Taurus and how the early ’90s Camcord (and even Civic and Corolla) designed at the tail end of Japan’s Bubble Economy were dripping with fat.

Never much warmed to the first generation colonnade Cutlass. That picture of the Grand Prix, Regal, Cutlass, and Monte Carlo says it all and easily shows the Cutlass as being the worst-looking of the lot.

And, yet, it was a very hot seller, probably because it was the least expensive entry into the same, intermediate, quasi-personal luxury car category as the others. Looking nearly as good for a lot less coin goes a very long way to explaining the Cutlass’ explosive popularity in the seventies..

Sadly, by the time the last real Cutlass rolled off the line in 1987, a scant ten years later after its peak, traditionally-sized domestic RWD coupes were on the way out and largely seen as an anachronism. The last RWD coupe hold-outs, the MN12 Thunderbird and Mark VIII, would hang in there until 1998 and, finally, the now FWD Monte Carlo would breath its last In 2007.

And, yet, it was a very hot seller, probably because it was the least expensive entry into the same, intermediate, quasi-personal luxury car category as the others.

I think you’ve put your finger on it. The Monte Carlo and GP, with their longer wheelbases, were positioned a notch higher. Meanwhile the Cutlass Supreme coupe looked close enough to them with the same basic roof, and obviously folks didn’t care about the missing extra length in the front end. One could say they were being quite pragmatic. The extra length in the front end not only cost money, but made the cars that much longer and harder to park.

If the Monte Carlo had taken the same approach, on a 112″ wheelbase and a wider range of trim levels, it might well have been the top seller in the segment.

But then the Olds name still had a bit of cachet.

What Chevrolet & Pontiac did was spread their intermediate models over 2 nameplates. Oldsmobile chose not to build a MC/GP style extended wheelbase coupe, but as you pointed out, folks chose the Cutlass Supreme anyhow.You’re right in that the Oldsmobile brand still carried a lot of cachet in that era, and I’d argue that they gave most of it away when they stopped using Oldsmobile engines later in the decade.

For 20+ years, the “Rocket V-8” defined Oldsmobile. When they lost that, they lost their cachet.

Chevrolet’s image wasn’t helped by the Vega and the notorious motor mount problems plaguing 1965-69 Chevrolets with the V-8 engine. Oldsmobile just had a better reputation in the 1970s than Chevrolet.

If I recall correctly, Oldsmobile management wanted the equivalent of the Monte Carlo and Grand Prix in 1970, but GM management said “no.” Oldsmobile did get permission to put the formal roof on the standard 1970 Cutlass…and the result was a huge hit.

Olds (and Buick) sales boomed in the early 80s, when Chevy and Pontiac didn’t. What killed Olds and Buick, aside from chintzy quality and lookalike corporate style, was that first time buyers went to Japanese brands in the early 80s and stayed with them.

I think the price hierarchy in the GM personal luxury category could be described as follows (from highest to lowest):

Eldorado

Riviera

Toronado

Grand Prix

Monte Carlo

Regal

Cutlass

Lemans

Malibu

So, Oldsmobile hit that sweet spot of having a (perceived) middle-tier coupe that could be configured with substantially more class and luxury than a plebeian Chevy Malibu or Pontiac Lemans (neither of which were anywhere near the personal luxury category), but at a much lower price than Grand Prix, Monte Carlo, or even Regal. The Cutlass became the de facto personal luxury entry point for a lot of people looking to move up. Can’t afford a Grand Prix or Monte Carlo? No problem. Here’s a nearly as nice Cutlass Brougham coupe.

In fact, I had a close friend who did exactly that. Not long out of high school, he had a ratty ’72 Malibu coupe with big/little tires and loud exhaust. As his job status improved and started thinking about marriage, his next ride was a ’77 Cutlass Supreme Brougham.

FWIW, Pontiac tried to get into some of that entry-level personal luxury action with the Grand Lemans (there was a good CC on it a while back) but Pontiac was definitely still GM’s performance division (Grand Prix excepted).

Personally, from ’73-’75, I’d have coughed up the few extra sheckles for a better-looking Regal.

Chevrolet’s total A body sales were fine. Chevelle did plenty of volume at prices under MC and Cutlass. I would guess that the 1977 B-bodies did much more damage to Chevelle than Cutlass, because Cutlass volume was mostly the stylish coupe, which didn’t look obsolete next to a Caprice or 88, esp with the squared off 76:77 coupe shell. The Chevelle was definitely yesterday’s news in 1977–the only reason to buy it was that it was cheaper (and less roomy and stylish) than a similarly sized B body.

Excellent exposition that proves that car buyers are faddists. As if that needed saying.

I liked the ’73 front end the best.

Great. Now I have this song in my head all day…

https://youtu.be/fQlKa1IeZF8

Never cared for the…dare I say….”flame surfacing” of the 73-75 Cutlasses. I preferred the Regal which came to market with a new name, setting upmaket from the previous Skylark and the “sweep spear” styling which was a Buick tradition.

I did however love the 77-78 Cutlass styling….very taught, clean and sophisticated.

My take, as well, but I think you mean ’76-’77 Cutlass. The 1978 Cutlass was the quite lame downsized version.

The blue 73 Supreme side view has a fair bit of Exner Stutz revival in the lines.

Good call. Ex’s last car was a 1973 Olds 98, allegedly recommended to him by Bill Mitchell. It had that sort of lower body sculpting, although not with the stop/start plucked chicken sculpting of the 73 Cutlass.

In his biography, the last known photo of Ex is with a 1972 Hurst/Olds (Cutlass Supreme) courtesy car at the Indy 500.

The article alludes to weight. I owned a ’76, and perhaps what I remember most about it was the metaphoric tonnage of the doors.

It’s interesting that the Ford designer says that the colonnade is a loser compared to traditional hardtop styling. In the line brochure cover, the Cutlass and the bigger cars have the same door size. Visually, the Supreme coupe has no back seat. The big cars look like school buses in comparison.

By the early Seventies, actual convertibles weren’t symbols of glamour, but still gutsy to go the other way. GM had established the V coupe roof on the Eldorado.

I’m pretty sure that quote is about 80% puffery — by that time, Ford’s new intermediates were certainly being designed and I’d be shocked if they weren’t considering ditching the hardtop as well. But I think that such a quote was made at all, does reflect how embedded hardtops had become in car design.

As a check, the later 77 LTD II and Cougar coupes executed the hardtop-style roof design features of the 72 fomoco midsizes with more angles and blades. The basic 77 T Bird roof had more of a colonnade style where the whole main opening was the driver’s door, and there was a disconnected window in the sail area (or a landau treatment that closed the window). The T Bird sold best of those Fords, tho the name at a popular price probably got everyone looking at it.

I remember on numerous occasions seeing the early Colonnade Cutlass (with the lower bodyside sculpting) with what looked like a ‘rust rash’ at the very base of the lower sculpting in front of the rear wheel arches. The downward facing part of the sculpting created a surface that appeared to align directly towards stones thrown by the front tires. This, I assume, was before lower body coatings were widely adopted to prevent stone chips. I’m sure GM would have seen this at the testing stage.

As the surface faces downward, and is near the rocker panel, it’s not readily noticeable standing near the car. I recall cars with significant unattended stone chips would show this ‘rust rash’ consistently in this location.

Yes, that rust rash was a problem with the extreme tuck-under. The 74-78 Chrysler had the same problem on the lower rear quarters that tucked under quite severely. Ask me how I know.

That rudimentary textured lower body coating that Ford starting using in the late 70s would have at least prevented the rust. That coating appearing so thick you could see the tapeline separating it, and normally painted surfaces. It also appeared to have a low gloss finish.

Thus the pop song “27 Jennifers” by Mike Doughty, although I can’t think of a pop song about Oldsmobiles. On the other hand the Camaro and over the pond the Cortina figure in several titles or lyrics.

There is the old pop song in my Merry Oldsmobile. It came out in 1905 but was covered by a lot of artists over the years

Here is the Bing Crosby version

Great article- and some thought provoking comments on the success of the Cutlass. Apparently Toyota took quite a few notes over the years because… let’s be honest… the Camry today is what the Cutlass was 40 years ago. And for many of the same reasons. Durable, reliable, easy to look at, easy to buy, easy to sell. History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

I have small classic vehicle collection . It won’t be complete without an Olds mine is 79 Hurst/Olds white/Gold colour combo with beige cloth interior has 7K original miles with all documentation and manuals! These were limited production I understand about 2500 made total. I paid $21,000 for it. No it’s not for sale.

One thing I noticed in GM Colonnade advertising at the time, that I hated, was they consistently showed the Colonnades appearing low to the ground. To me, it gave them a dated ‘lower, wider, longer’ appearance more in common with the 1950s and 1960s. Accentuated by their baroque styling. More of a luxo-barge visual quality somewhat akin to the bloated B-bodies.

IMO, the Colonnades looked most fresh and agile with normal ride height, and styled steel wheels.

Was just able to read this, it’s an excellent piece Eric! You’ve managed to capture exactly why this car became so popular and ultimately, how it’s popularity declined yet Oldsmobile still kept trying to capitalize on its former success. Very enjoyable read!

And I actually never knew about the reversible seat cushions before!

I never knew about the reversible cushions before this either — I love learning new stuff like that. But I simply can’t imagine what kind of junk must be hiding under the cushions of this car’s seats!

My wife’s name is Jennifer (well, it’s spelled Jenifer, missing an ‘n’). She was born ’92, as was I.

I don’t think there’s a 1992 MY car that I would assimilate her to, so she would be a W212 E63 AMG 🙂

Great write-up Eric, the comparison to the Jennifer name was just perfect. There is no doubt the Cutlass Supreme was a massive success story. The PLC was the rising trend in the 1970’s and I think the Cutlass Supreme ended up being the poster child for a number of reasons. A big part of the appeal to a PLC was the luxury options, the cachet and the style. Chevrolet and Pontiac dealt with this well, by introducing the Monte Carlo and Grand Prix. Having the exclusive styling, that differentiated it significantly for the run of the mill intermediate cars was necessary to give these cars some appeal. I’d argue Chevrolet and Pontiac almost let their intermediate sedans wither on the vine during these years.

The Cutlass Supreme didn’t a major differentiation in styling, it had something that the Chevrolet and Pontiacs didn’t – brand appeal. The Oldsmobile name at the time had a lot of value, and you could get into a Cutlass Supreme for far less than a Grand Prix and even less than a Monte Carlo. Why not step up to an Oldsmobile, rather than driving a poor old Chevy?

Of course, the Cutlass was a fundamentally decent car, and Oldsmobile kept it fresh . The build quality was good, styling was up to date and trendy, it’s size was manageable (for the era) and it had a decent powertrain. The 350 Olds was not a barnstormer, but it had a reputation of being a long lasting quiet engine. The Q-jet carburetors were well designed and could cope with emissions standards fairly well, which resulted in better driveability to many of its competitors. In the end, it was a decent car, that was in style and it had excellent brand power.

Sacred poo (i.e., holy ѕhіt), really? I would never have guessed it to be that high. I guess that helps explain why one almost never sees a 4-door or a wagon any more—well, that and the wagons having been used up in hard service, and the sedans having been cut up for parts to rebuild 2-door cars.

I was all set to ask if you’re sure about this, because I could swear I remembered the same taillamps on my father’s ’77 Cutlass Supreme 4-door, but browsing around on the web suggests they weren’t quite identical: same lens mould, as it seems, but minus the chrome strip down the centre. In any event, they did seem to have a lot of taillight variants on the ’75-’77 cars, didn’t they. Offhand I can think of five, and there are probably more than that.

This was a fun read and there is so little hating from The Commentariat. I particularly liked the bar graph showing the sales breakout. A lot of thought went into this write-up. “Thanks” from one of the biggest Colonnade fans out here.

For some reason I never liked the olds version of the colonade. The styling to me was worst of the bunch. I much prefered the grand prix and montecarlo. But the regals and LeMans looked better too. Chevelle was about as ugly. I really am not that big a fan of colonade cars. Would rather have a t bird or cougar or LTD 11. Or a cordoba

I like the antique Virginia license plates. The font has a military look to it. You’d think it was driven on a military base by an officer. I remember that the fuel filler on my mom’s 1977 Cutlass Supreme Brougham was behind the rear license plate, which you tilted down to access. Here is a Japan-spec 1977 Cutlass Supreme with amber turn signals.

Good guess about the military officer — this is a close-up of the parking decal on the front bumper. I believe these decals date from the 1970s — not necessarily indicating an officer (could be a civilian employee), but this Supreme definitely spent some time commuting to a naval base. This decal itself is quite a relic… after all how many 40-year old parking decals do we see these days?

I like the Japan-spec Cutlass — a Salon no less. I’ve never seen an example with amber turn signals.

⬆︎Japan-spec car with amber turn signals: that thing where I’ve never seen a particular item, but I have an idea of just what it would look like, then I see the actual thing and it’s just like what I imagined.

I had one of these later in college, a ’75 Hurst/Olds. In spite of the W30 decals on the fenders, the low compression 455 was more befitting of Custom Cruiser duty. Still, it drove well, rode well (one of the best long distance runners I’ve owned), and after swapping in a ’74 transmission cross member and adding true dual exhaust it had that unmistakable Rocket V8 burble. Wish I had it back.

Also wish I had back the ’76 Toronado I inherited from my Dad, but that’s another story.