(first posted 1/22/2017) All good things come in threes and the best is usually left for last… Let’s see if you agree with these platitudes as we consider our final sports/luxury French Deadly Sin. The Bugatti was a myopic stab at rekindling a slumbering brand. The Facel was an attempt at diversification that went horribly wrong. But the Monica 560 was a different thing entirely: one man’s folly that spent years in “development hell”, resulting in a small batch of very attractive but eye-wateringly expensive saloons.

Monica 560: A Star Is Stillborn

Even wealthy and successful industrialists have their little foibles. Jean Tastevin (1919-2016) was such an industrialist. His business, the Compagnie française de produits métallurgiques (CFPM) was specialized in building and renting freight rail wagons. The family company he inherited became, thanks to his astute stewardship and dedication, a European leader in his field: 25% of freight cars on European railways came from CFPM’s works located in Balbigny, a village in central France.

The plushest French car on offer in 1966 was the (non-Deadly Sin) DS-21.

But Tastevin’s real passion was always cars. He had had Delahayes and Aston-Martins in the ‘50s and Facel-Vegas in the early ‘60s, but now, in 1966, he found himself having to shop for a Jaguar. He wondered why France had lost all its automotive prestige: not a single 6-cyl. engine was to be found among domestic automakers. Nothing over about 2 litres of displacement, either. The only “luxury saloon” available was the all-too-common Citroën DS, with its ancient, agricultural-sounding four-pot.

The 1961-64 Facel-Vega Facel II was the last French GT – albeit with a Chrysler V8.

Jean Tastevin’s patriotic pride was piqued, as European sixes and V8s weren’t exactly rare in 1966. Italy had Alfa Romeo, De Tomaso, Fiat, Iso, Lancia and Maserati (as well as V12s by Ferrari and Lamborghini); Germany had Glas, Mercedes-Benz, Opel and Porsche; Britain had AC, Alvis, Aston-Martin, Bristol, Daimler, Jaguar, Jensen, Rolls-Royce, Rover and Triumph (not to mention BMC, Ford, Rootes and Vauxhall). Even Czechoslovakia could muster the Tatra 603. Tastevin saw this and he saw his company’s healthy finances, and thought he was the ideal man to redress this dire state of affairs. Besides, there was a need for the CFPM to diversify its production. He was going to build a large supercar – probably a coupé.

But who could assist him in this ambitious endeavour?

Chris Lawrence in 1972 and his 1963 Le Mans racer, the interestingly-named Deep Sanderson.

In 1967, our rail magnate met Chris Lawrence (1933-2011) in England. Lawrence was a racing driver and engineer who had worked for Morgan, Marcos and Triumph, and had created the Mini-based Deep Sanderson racer. He was soon convinced that Tastevin’s hunch about there being a place in the sun for a new large French car was correct. Jean Tastevin had great contacts within the French administration, as well as a sizable factory and considerable resources. Lawrence possessed the technical know-how, as well as an interesting source for a potential engine: Ted Martin’s new V8.

This was exactly what Tastevin needed. He knew that in any automotive project, the most difficult and time-consuming part of the operation was the engine, and he was determined to make his own. The Martin V8 was a racing engine created in 1963, originally a 2-litre. It had already been tested and run on Lotus and Pearce racecars. Of course, it would need to be completely reworked to power a road car, but at least it already existed. Lawrence and Ted Martin set to de-tune, bore up and strengthen the all-alloy V8, which ultimately grew to 3.4 litres and used four double-barrel Webers to reach over 240 hp @ 6000rpm. It remained a remarkably light (100 kg / 230 lbs with all ancillaries) and compact engine.

A small clutch of engineers managed by Lawrence in England also devised a chassis for the motor: longitudinal V8, De Dion rear axle with trailing arms and Panhard rod, tubular backbone chassis with a triangulated space frame, rack-and-pinion steering, power ventilated disc brakes (in-board at the rear) and a five-speed ZF gearbox. A rolling chassis was tested at Silverstone in late 1967.

Prototype number one re-emerged a few years ago (below) and is getting restored.

By April 1968, the chassis was bodied by Williams & Pritchard, a small London coachbuilder better known for racecars. Jean Tastevin, who had changed the brief to a four-door saloon, was convened across the Channel to provide feedback. He was very disappointed in the car’s looks, but at least the chassis and engine seemed to be on the right track.

Clearly, the body was not what he was looking for. It looked uncannily like an overgrown Panhard CD (which was no oil painting). The engine was said to also run a bit like a Panhard (quite rough), but Lawrence was quite certain that with a little more tinkering, it could be brought under control.

The second prototype also survived and is getting restored.

The team went back to the drawing board and bodied a second prototype chassis with Tastevin’s instructions in mind. It was ready by early 1969, but its styling was also deemed unacceptable. Tastevin now figured that he should take the matter to folks who knew about building elegant cars. Tony Rascanu, a Romanian émigré who used to work for Vignale, drew up detailed plans for the new body, which were sent to Henri Chapron in Paris for the carrossier to build a full-size wooden mock-up. Both the mock-up and another prototype chassis were then shipped off to Vignale in Turin.

Prototype #2 (left) and the Vignale car, circa 1970.

But there was a snag: in late 1969, Vignale sold his carrozzeria and retired (he was sadly killed in a road accident days later). The Vignale works were in disarray after these events and work piled up – including the French prototype, which Tastevin thought might be built in Italy. It took months for Vignale, who had to subcontract most of its operations to other firms, to build the third prototype. But by mid-1970, the car’s styling was deemed on the right track by Jean Tastevin. However, given Vignale’s closure, the production of subsequent prototype cars would have to be done elsewhere: Airflow Streamlines of Northampton built about five Monicas in aluminum in 1971-72; all subsequent cars would be made (of steel) in Balbigny.

The Vignale car (above) was a bit narrower and taller than the svelte finalized design (below).

It seems the car’s name was decided around this time. The Monica moniker came from Monique, Jean Tastevin’s wife. The finalization of the Monica’s styling and chassis were a tremendous reward for Tastevin. He tabled for a start of production in Balbigny in 1972, as soon as the Martin V8’s remaining issues were ironed out. Perhaps the fact that there were still issues to be sorted with that engine three years in should have alerted the rail magnate as regards the V8’s intrinsic qualities (or lack thereof)…

Even the period press seemed confused as to the Monica’s actual appearance.

The motoring press started to echo rumours that a new “French Jaguar” would be coming soon. Throughout 1971 and into 1972, more prototypes were built and tested. The car’s shape and detailing was further refined by David Coward, formerly with coachbuilder James Young, as the creator of the Monica’s original shape, the mysterious Tony Rascanu, had committed suicide in 1970.

The car was finally unveiled at the October 1972 Paris Motor Show, complete with its bespoke V8 and a lavishly appointed interior. It was met by quizzical looks from the French motoring press, who were not allowed to take one for a spin, but did report that the car would be sold in 1973 for about FF 100,000 (the price of two Citroën SMs, or twelve 2CVs) and that an annual production of around 400 cars was expected.

Rolls-Royce were contracted to manufacture the Martin V8 at Crewe. At the last minute, Tastevin added a clause: could Rolls-Royce provide a warranty on the engine and guarantee the power output? Rolls-Royce, who had not designed the engine, replied in the negative. Concurrently, one engine had been sent over to Italian specialist Virgile Conrero, who pronounced the temperamental V8 unsuitable for a road car. It was curtains for the Martins. Six years of development and a dozen prototypes gone up the proverbial. The Monica was nevertheless shown at the February 1973 Geneva Motor Show, where the pan-European automotive critics fêted it as a long-awaited entry from the country that begat Bugatti into the market of exclusive, 220 kph saloons.

Compared to 1967, however, that niche was getting pretty crowded by 1973. The Jaguar XJ-12 had just been launched – a prestigious 5-litre V12 saloon for an unbeatable price. Italy had the Iso Fidia and the De Tomaso Deauville on offer, and a few well-heeled punters could afford a Swiss-made Monteverdi 375/4, all of which had huge and powerful American V8s.

The Bentley T1 and Mercedes-Benz W116 (available with a 4.5 litre V8 from mid-’73; the 6.9 litre 450 SEL came in 1976) were less exotic, but all the more dangerous as rivals. And others had yet to join the party! In 1974, Maserati announced its long-awaited Quattroporte II and Aston-Martin presented a four-door Lagonda based on its current V8 coupé (though both were, ultimately, major duds).

Meanwhile, back in early 1973, the Monica needed a new motor – pronto. Perhaps remembering his old Facel-Vega, Jean Tastevin swallowed his pride and called upon Detroit. At the time, Chrysler V8s were found in Monteverdis, Jensens and Bristols. Just the sort of company Monica was aiming at. Mopar duly provided a few 5.6 litre (340 c.i.) V8s, which were mated to the car’s ZF gearbox. Unencumbered by emissions standards, the Chrysler V8s proved more than adequate for the job. What they lacked in exclusivity and refinement, they more than made up in durability and power. The car would now be called the Monica 560.

Madame Monique Tastevin and the car that was named after her at the Castellet.

A couple of the Chrysler-powered cars were presented to the automotive press at the Castellet racing circuit in May 1973. The tricky part was to fit everything inside the Monica’s front end, which originally hosted the fuel tanks (one on either side) and a much smaller all-alloy V8. Fortunately, the chassis tolerated the Mopar V8 pretty well.

Throughout the remainder of 1973 and into 1974, Monica’s engineers modified the Chrysler engine’s compression ratio, camshafts, pistons and heads to squeeze out even more power (285 hp (DIN) @ 5000 rpm), but were left with overheating issues that proved time-consuming to sort out.

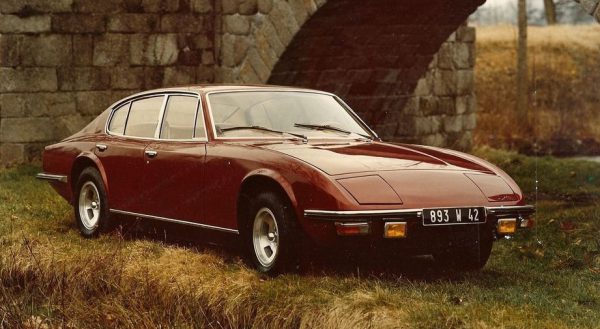

Later “production” cars like this one had a revised dash and thinner front seats for better rear legroom.

By the spring of 1974 though, the Monica 560, a 240 kph V8-powered rocket ship with Connally leather trim and superb handling, was ready at last, in both manual and Torqueflite flavours. But the world, alas, was not in the mood any longer. The OPEC-led fuel crunch was the order of the day. Everywhere, governments were enacting speed limits and queues formed at gas stations.

“Production” version with slightly larger air intakes and rectangular grille; official brochure below.

The Monica 560 was back at the 1974 Paris Motor Show, but its price had ballooned to over FF 160,000 – about FF 10,000 higher than the SM Opéra and FF 50,000 more than the S-Class Benz. Production had started timidly at the Balbigny factory, but sales were disappointing to say the least. After only 17 cars were sold, in February 1975, Jean Tastevin called it quits. The Monica experiment had cost him seven years and millions of Francs, but enough was enough.

A number of unfinished cars and body shells were still at the factory, lacking an engine. They were shipped off to fellow small car-maker Guy Ligier, who was assembling the last batch of Citroën SMs as well as his own cars at the time. Numbers vary from one source to the next, but it seems that about 22 cars (some being pre-production models) were finished and registered with the Chrysler V8. About a dozen Martin-engined prototypes were made, and at least 20 cars were left unfinished, most of them ending up being crushed in the early ‘80s after their sojourn in Ligier’s back lot.

Unlike Bricklin or Dale, the Monica was a serious attempt at a new car, but it was a Deadly Sin. Tastevin tried to pull off a Ferrucio Lamborghini, but probably he farmed out and delegated too much. The Martin V8 episode and the ugly prototypes were the result of his management of the project, which had been left to Lawrence, who had no experience in making this sort of car. This consumed a great deal of time and treasure, neither of which are eternal. When the car was finally ready, the segment was overcrowded and the economic climate had changed.

Voilà! Another gruesome threesome of French Deadly Sins from the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s. Hope you enjoyed reading these as much as I enjoyed writing them.

Fugly. Like a Bitter squeezed through a pasta machine.

This is a much-needed profile on a curious automotive footnote. Would love a writeup of Ligier’s own roadcars and couldn’t think of anyone better to do it, T87.

Duly noted, Don! I know very little about these myself, so it would be a good opportunity to learn.

A lot of folks said of the Monica that it looked like a Maserati Indy with two extra doors. Never thought about the Bitter — there’s a bit of that too…

Never liked the Indy either. Nor Giugiaro’s Ghibli for that matter. Khamsin, on the other hand…

Regardless, your contributions here are quite literally invaluable. Many thanks.

Fascinating. I have only the vaguest memories of this bad dream, but never read a proper write up of it. And it was superlative, like all of your others.

Yes, all the classic mistakes, number one being hiring a race car driver who had built a Mini kit car out of fiberglass. Yes, obviously he had all the requisite skills.

Yikes; the ugliness of those early prototypes. What were they thinking?

The final car has some charms; reminds me most of the Lagonda, but without the charm of its front end.

Well, it did finally get a proper engine; the Chrysler 340 was a gem, and under-rated at 275 hp.

I can sort of see his initial rationale for this. He should have just farmed it out to someone who already knew howto build cars like this…in Italy.

The Monica story is, as you said, a collection of classic mistakes. So many “what ifs” — what if the project had been spearheaded by someone who knew what they were doing, what if the Italians had been involved in styling it from the get go, what if the engine had been this one or that, what if the car had been launched in 1970 instead of 1974…

Tastevin had so much rotten luck to go with his questionable decision-making, it’s almost comical. It’s a DeTomaso Vaudeville.

Very informative and extremely insightful. Thank you!

I had no idea about the Monica. That’s actually surprising because at that time I was devouring every issue of “Auto, Motor und Sport” to the last letter. Could they have missed reporting on this project?

I find the production version very elegant and the interior is stunning. a beautiful car born as an ugly duckling and a story with an ugly ending.

On the engine front, Rolls-Royce should have just suggested their 4-litre Twin-Cam version of the FB60 Inline-6 engine over the unsuitable 3.4-litre Martin V8.

Since the 4-litre Twin-Cam Rolls-Royce Inline-6 was not only more powerful then the Marin V8, but also produced similar power to the Chrysler V8 as well as adding some much needed cachet to what was essentially a new French luxury marque with an unknown pedigree.

Or even opportunistically acquire the 4-litre Maserati V8 prototype engine from when Citroen became bankrupt in the same period, which was tested in a Citroen SM prototype and produced similar power to the Chrysler V8 as well as the Twin-Cam Rolls-Royce Inline-6 engines.

http://autoweek.com/article/1974-citron-sm-v8-mystery-no-more

Well, the Maserati timeline wouldn’t have worked — it was almost curtains for the Monica already by the time Maserati and Citroen parted ways, and Citroen would never have allowed Tastevin to use that V8, I think.

But the RR engine sounds interesting, I don’t know about that one. Was it ever used in real world applications?

The non-DOHC 175 hp version of the all-alloy 4-litre RR FB60 Inline-6 powered the Vanden Plas Princess 4-litre R and was going to power the Austin-Healey 4000 prototype (with an automatic version reducing the power to 160 hp yet still being significantly quicker), had BL not cancelled the project due to Jaguar people within BL seeing it as a threat to the E-Type.

It was also planned to feature in the ill-fated BMC ADO30 sportscar (even spawned a Bentley proposal called the Bentley Alpha) as well as various BMC-RR joint projects, around the time when both companies along with Associated Commercial Vehicles / ACV (prior to Leyland acquiring the latter) temporarily considered merging into one combine,

The planned Twin-Cam version dubbed the G60 would have allowed the 4-litre RR Inline-6 engine to put out 268 hp with the potential for an easy 300 hp.

Austin-Healey 4000 prototype – http://www.ewilkins.com/wilko/ah4000.htm

Nope. Had Sir William Lyons not kyboshed the Austin-Healey 4000 (which was to use the FB60), it’s conceivable that it might have, but it would have been a direct competitor for the 5.3-liter E-type.

Lyons also killed off Daimlers excellent V8 which could have gone into the Healey body or for that matter the Monica, it was tried and proven when killed off to remove competition from Jaguars XK 6.

I knew about the Monica – but only from a long story in either Octane or Classic & Sports Car within the last couple of years. The Iso Fidia has always been a favorite of mine and I see one at local Arizona car shows frequently. The competing Monica looks as good to me; I especially enjoy the rear 3/4 view.

Back in the day when it was new the Monica would have made a good subject for a Solido 1/43 scale model.

Yes, Martin Buckley wrote an article on the Monica for Classic & Sports Car.

Fascinating. I rather like the looks of the final version, and, being a fan of the Mopar 340, speculate that it would have been quite a nice GT car, although I wonder it if had the classic French-ride body-leaning handling.

Interesting to look at the French approach of “nothing but the best, and most of all, it must be original” compared to the English, “Well, we can use a tractor transmission, even if first gear is too low; we’ll just block off the shifter so you can’t put it into first”.

A folly, if I ever saw one. I’ve always been fascinated with this car, but there’s so little information out there of it. This may be the most extensive article I’ve read on it.

And yes, it was a pipe dream trying to make a car like this in France at the time, because they didn’t have the infrastructure to support it. The reason most supercars are made in the vicinity of Modena is because they have a cottage industry of the best supercar people in the world living there. They have the best panel beaters, and they have the best engine builders. It’s telling Tastevin had to farm out most of the work to both England and Italy, making the car prohibitively expensive doing so,

Looking at the photo of with the doors open. it seemed to me of that it was more of a four door coupe, like the mid 2000s Mercedes CLA550. I don’t know about their reliability, but I do like their looks. I guess they couldn’t be any worse than a Jaguar

Bravo! I have so enjoyed this series!! As a teenager I would read about the forthcoming Monica.. . Sad the run was so short, I find the production version quite beautiful. the dashboard reminds me of the Facel-Vega.

TATRA87,

I have really enjoyed your series on French auto manufacturing history.

Thank You

Thanks for writing about the Monica – a car I had only seen in the annual Observer’s Book of Automobiles for a few years in the 70s (and always the same picture). To a six year old a four door saloon with pop-up headlamps was deeply cool.

Oh, how I love this series! Brilliantly written and absolutely fascinating. More please!

Any plans to write about Delahaye, Delage, Salmson?

Hehehe… There’s more Deadly Sins to come for sure. The Delahaye 175 would be a good candidate. But I might do a few on other countries before that. Britain produced so many interesting ones, for instance…

Britain could screw up a wet dream…bring it on please Tatra87!

Epic failure aside, the dashboard on the Monica is a true work of art.

What a wonderful read. Thanks!

Great story on a car I knew very little about, thanks.

I was admiring the wheels & I noticed, only 4 wheel studs, bit underdone for a car of this size & power.

Making stylish cars was never a French specialty.

Unless, it’s a Renault Clio in full Rally GT Turbo form, never really cared for them…Say except the 30’s Bugattis.

The Veyron is ugly as sin, looks like a computer mouse.

The Monica 560, was a good looking car…Although, would look a lot better as a 2 door coupe.

I’d seen photos of this car before, but never knew exactly what it was–thank you for solving the mystery! I think I had assumed it was a Maserati of some sort, as it does bear a passing resemblance to the Indy up front. I do find it rather stylish, though, and that interior is beautiful! If it had come out closer to ’70 than ’74, and if they’d gone with Chrysler power right off the bat…maybe it would have been different, If, if, if, The Deadly Sin mantra!

The 1968 Williams & Pritchard bodied prototype looks like it was styled by the same people who did the ill-fated and extraordinarily ugly 1957 and ’58 Packard Hawks!!!!

The Monica was the surprise star of the motor show at Earl’s Court in 1973 or ’74.

I went with my father, going to see the Lamborghinis, Ferraris, Maseratis, Aston’s etc and knew nothing at all about the Monica until I saw it. A stunningly beautiful car in dark blue with cream leather upholstery.

My father got me the particulars and I had a an A4 sized photograph of the Monica on my bedroom wall. No one ever knew what it was.

Thanks for this great write-up about the history. The 60s and 70s were a special period in car design.

Great indepth Tatra, Ive read about the Monica before cant remember where but there was far less information these small supercar developers come and go sometimes they leave cars as proof of their ideas sometimes not.

Always interesting how some people, seemingly excellent in one field, are completely out of their depth in another, despite, or perhaps because, of their enthusiasm. You see this all the time in sports ownership, and here is perhaps an excellent example in automobile company ownership. Yet one thinks, if he was that enthusiastic, he might have visited England a few times early on to see what was going on, especially on the styling front. I mean, wouldn’t you have a design review before the thing was built in the metal? Isn’t that common sense? Anyhow I kinda like the car in it’s final form.