(first posted 1/22/2013. A fitting companion piece to today’s Sterling CC) After Rover’s promising start with the advanced P6, it didn’t take too long for their relationship with North American consumers to sour. Perhaps it was its overly complex design, or the poor dealer network, but Rover cars quickly gained a “lemon” reputation. As a last-chance shot at redemption, Rover made an effort to right the wrongs with the simplified, handsome and V8-powered 3500 (better known as the SD1)–but it was not to be.

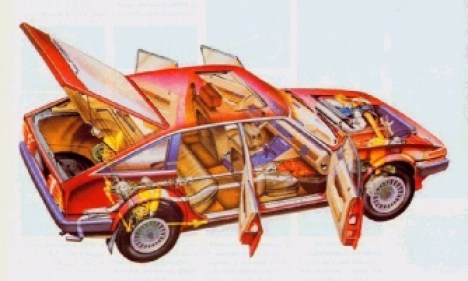

On paper, the outgoing P6 Rover–in its twin-carburetor, four-cylinder 2000TC variant, and even more as the 3500 V8 version–was a remarkably advanced (and complex) car. It was a sophisticated, sporting, luxurious saloon that was more affordable than a Jaguar and offered more performance than a Mercedes. After failing to live up to the hope and hype in North America, Rover retreated from that market for a serious re-think.

While the P6 styling was strong, the car certainly had a few quirks, including its extra-tall front turn indicators. Since British Leyland intended to replace both the P6 and the Triumph 2000/2500 saloons With its intended successor, styling proposals were accepted from both Rover and Triumph. The Triumph team’s effort was code-named Puma, and featured Michelotti styling; the Rover proposal, named P10, aimed to once again leapfrog the competition with an unusual and large hatchback design.

The Rover team, which was headed by David Bache, edged out Triumph, and British Leyland went with the more daring and exotic styling direction. It was initially renamed RT1 to indicate both Rover and Triumph influences; however, the corporate masters decided Triumph should focus on smaller cars, and the project was renamed SD1 (Specialist Division Number 1) as a Rover exclusive.

Clearly, the SD1 took some styling direction from the groundbreaking 1967 Pininfarina BMC 1800 concept. It wasn’t the only car influenced by that very advanced concept, which also inspired the Citroen GS and CX, among others. One of the SD1 proposals included exotic and cutting edge (for the time) scissor/gull wing-style doors; thankfully, these didn’t make it to production on both cost and sanity grounds.

Pininfarina’s 1968 Ferrari Daytona was another obvious influence, especially at the front and the concave side accent line. The Daytona style was watered down a bit for the North American market, since Rover was forced to fit dual sealed-beam headlights in place of the European lenses. The fenders were reworked slightly as well–as a friend of mine found out the hard way when he tried to repair his collision-damaged Canadian car with a British-market fender.

The SD1’s mechanical specification was greatly simplified from the earlier P6, and to many it looked rather like a seriously retrograde step. The complicated and costly deDion rear suspension was tossed in favor of a conventional live rear axle; fortunately, it was well located, utilizing Watts linkage, and proved to be more than acceptable. Also, rear drums replaced the disc brakes. Just to prove it wasn’t going all caveman-tech, there were self-leveling shocks at the rear and standard radial tires, although the latter was pretty typical by then.

Up front, the almost ubiquitous MacPerson-type struts were utilized. The power steering system was updated, now requiring only 2.8 turns lock-to-lock. The SD1 was very well regarded in terms of both quickness and handling feel. Any unique P6 engineering had been erased by the run of the mill, time tested solutions on the SD1. It all looked very promising–especially for the North American market, whose customers and mechanics didn’t generally appreciate the advanced tech once the car actually drove off the lot. In the UK, the basic specification made the Rover much more appealing to the very large and important company-car market.

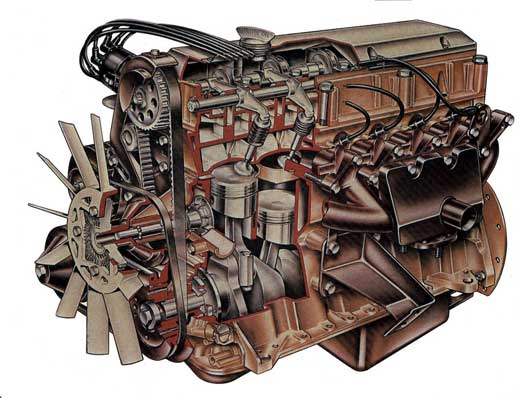

Engine wise, the SD1 was only available in the North American market with Rover’s fine 3.5-liter, all- aluminum V8. Purchased by Rover from Buick, it enjoyed a prosperous second life in several Rover saloons as well as Range Rover, Leyland P76, MG B-GT V8, Triumph TR8, and innumerable British specialty vehicles. It was truly the UK equivalent of a small-block Chevy V8.

Released initially in dual SU carbureted form, the V8 was eventually fitted with Lucas L-Jetronic fuel injection in order to meet emissions regulations in North America. The SD1/3500 could be fitted with either Rover’s fine LT77 five-speed manual gearbox or, more commonly in North America, a Borg-Warner three-speed automatic. The five-speed’s 0.83 overdrive ratio gave the Rover fine high speed cruising ability, as well as impressive-for-the-era acceleration.

European cars achieved 0-60 times in the eight second range and a top speed of 125 mph; the North American cars were only slightly slower–not bad for a good-size car with a claimed 26.2 (Imperial) mpg. It was both faster and more economical than almost all its European rivals, many of which cost significantly more. Understandably, early press reaction was extremely positive.

Back in the UK, other engine options soon became available following the V8-only launch. Obviously, a smaller engine was needed for the 2200/2200TC as well as the Triumph 2500. At the time, V8s were out of the price, tax, and fuel economy ranges of most European buyers (even of premium brands), and were very uncommon.

The Rover four-cylinder, which was considered a bit crude even back in the 60s, was not considered, but in 1977 the Triumph straight six was offered in 2.3- and 2.6-liter versions. Originally, the six-cylinder was supposed to be a straightforward SOHC conversion of the Triumph 2500/TR6 unit, but ultimately was so extensively re-worked that it ended up a completely different design from the OHV unit, with which it shared no parts. Starting in 1982, a more economical 2.0-liter O-series four- cylinder was also offered, which was especially important for company-car sales. A 2.4-liter four-cylinder diesel was also on tap for those who valued fuel economy over any kind of performance.

Inside, the SD1 once again differed dramatically from the earlier P6. Gone was any trace of traditional wood, as the designers had gone for a very modern seventies-minimalist design. With an eye to export markets the dash was symmetrical, with an instrument cluster in a pod and a swappable steering column and heating vents. The second glove box, under the steering column, is a rarely seen nice touch. Unfortunately the materials, although nice to look and touch when new, didn’t seem to hold up very well over the years, eventually giving older examples a bit of a rundown look. North Americans also missed out on the oh-so-’70s steering wheel featured in the home market, instead getting a three-spoke unit that looked to be lifted from a TR6 or MG B aftermarket catalog.

Given the positive press reaction, consumer buzz and multiple car awards in the European market, the future of the SD1 looked rather rosy–but this being British Leyland, one just knew they were very capable of snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. And they didn’t disappoint in that regard.

It began by launching the car in the spring of 1977 without a supply adequate to meet the demand. In the home market, lightly used examples were being sold for more than list price–rather ironic, given their extremely poor resale value a few short years later. It didn’t take long for whispers about quality control issues to become shouts. Predictably, there were worker strikes as well, with some cars taking up to six to eight weeks to produce. Just as Rover was able to tool up to meet the large initial demand, it sharply dropped off. The UK cars would gain a minor facelift and several further enhancements to quality, but the North American cars didn’t last long enough to benefit.

The Rover 3500 wasn’t certified for U.S. sales until 1980. In that year, sales in the all-important U.S. market amounted to a paltry 480 units. Technically, the following year’s sales numbers improved, all the way to a whopping 774 units, but that figure included a lot of leftover 1980 models (There are also a few titled as 1982 models, which are really unsold 1981 carryover units). While growing up, I remember seeing a reasonable number of 3500s, and I’ve a number of friends who owned one, but Canadian sales numbers seem to be impossible to track down. Given that the Canadian market, as a whole, is smaller than California’s, the totals were probably still quite small despite the relatively greater popularity.

In the storage yard are two examples to choose from: Both are similar, with the grey one being the earlier of the two and titled as a 1980 model. It has the fuel injection and automatic gearbox, which probably kept it from being used as a donor for an MG B V8 swap over the years.

The second example, while titled as a 1982 model, was produced in 1981 and sold as left-over stock the following year. It’s in slightly better condition than the grey one but again, fuel injection with an automatic transmission limited its appeal to me. This one also has a sunroof, which was one of the few optional extras for the very well-equipped North American-specification cars. A four-barrel Holley four-barrel carburetor, which reduced servicing headaches and boosted power, was quite a popular swap for these.

The 3500 SE was disastrous enough to chase the Rover nameplate from the U.S. and Canada for good. When Rover thought (again) they had the winning formula with a new car full of Honda engineering, they went with a brand new name: Sterling. That sad tale was told here, and maybe will be retold on another day.

I remember when I was selling VW-Audi in 1987. A couple came up in a 1980 model of this wanting a trade on a Jetta. I laughed them off the lot. No, I didn’t sell them a car. No, I didn’t care if I never saw their faces again.

That sounds pretty mean…

…and pretty VW dealer-esque

Yep, looking back, I was kind of a dick, LOL.

Dick, or no, you did the right thing…though to be fair, weren’t you guys pushing the VW do Brasil Fox at the time?

I actually feel bad for the people I sold Foxes to. I really believed it

to be a decent product at first.

Those were just hitting the dealer when I bought my 85 GTI towards the end of the model year. I thought they would be nice basic little cars too. I saw one parked at a house in my neighborhood last summer, but had no time to stop for a picture. By the time I came back, it was gone. First one I have seen in eons.

The Fox always struck me as being hit-or-miss; my wife and her ex had one years ago as a young couple in Watertown, NY, and in spite of the brutal climate it was solid in every way. Having said that, I’ve seen more SD1s in the wild over the last five years (three), than I have Foxes (zero). Strange, but true.

CC effect. I saw a Fox wagon on the road yesterday. First one I’ve seen in ages.

My own memory of the Fox was short but positive…the ex bought one, or we bought it together, for her use.

One drive and she was sold…after driving an Escort, a Colt, and a Corolla. And when her father bought his middle-age toy, a Scirocco…she was pleased that she got the same handling and solid feeling for less than half the price. And her father, a German, believed implicitly in Volkswagenwerk engineering.

But when she drop-kicked me out, the Fox stayed. Ten years later I saw it parked at her parents’ farmhouse…and never again.

But…it made it ten years, anyway, which made it seemingly cost effective.

I might second…yes, refusing to talk to someone with an undesired car as a trade-in…typical VW dealership tactics.

The true difference between the German car companies and the Japanese ones: The Germans tend, or tended, to offer superior engineering and assembly; sold and serviced by people with the ethics of grave robbers.

The Japanese understood the importance of continuing the relationship between the company and its customers…not a one-time exploitive transaction, but a longtime, hopefully serial relationship. So…who did better? The companies with bland Asian cars; or the ones who made flashy, performing Euro sports sedans, and let their customers have it in the shorts?

I had a 1981 Mazda. The warranty service at the San Francisco dealer was consistently beyond abysmal and appealing to the district guy or Mazda was pointless. It wasn’t just me – one time back then the car guys on NPR talked about it.

My used car manager used to use the non-PC term, “a car with AIDS” to describe cars like these, Sterlings, Peugeots, etc.

Ooh. I’ll take a peugot. Anything early 90’s and older. — the sd1 was a good looking car. I wud have loved to see the micholotti design.

omg I had one lol

That dash has got to have one of the cheapest looking instrument clusters I have ever seen. No attempt to seamlessly integrate the instrument cluster with the car was apparently taken. Instead, it looks to have been just dumped on the side where the steering wheel was.

It was a stylistic fad, like in the contemporary high-tech architecure. It was supposed to look like plug-in units, just plug-and-play….

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High-tech_architecture

It was very cool and stylish in its day.

I owned a 1980 Rover model 3500. Quite an interesting and innovative car.

5 speed, hatch back, enormous storage capacity, Buick aluminum engine, fuel injection, very advanced styling.

Mine was silver. I had it for five years and it had only 6,000 miles…because it was in the shop all the time.

Incredibly it was serviced by Rolls Royce of Manhattan and I was able to get the warranty extended for the 5 years because of so many safety problems: windshield leaked, at 70 MPH the car just stopped at least three times, on the highway at midnight the headlights simply shut off, the wipers would start and not turn off, the car overheated constantly. Obviously Lucas electric’s reputation was present.

But I had a real love/hate relationship with it. After RR refused to service it because they made more money on the Bentley and RR, I used a local mechanic. It was in his shop so much that he ended up buying it from. End of story.

I like it. The instrument pod looks like it’s supposed to be retractable into the dash.

The later models of the SD-1 got a much nicer dashboard (see attached picture).

Unfortunately, these never made it to the US.

And actually, it wasn’t so much a departure from the P6’s dash as a ’70s update.

P6 dash below… same ‘gauge cluster sitting on a tray’ look, even has the central passenger vent.

That is because it was an actual design feature to alow switch between LHD and RHD using shared components and reduced cost. I personally like it even though unusual for a more premium brand car.

Later facelift cars had better build quality though the damage had been done by then.

Vitesse is the model to have over here with twin-plenum EFI.

I happen to like the SD1/3500, and I’d love to get one of the from that storage yard, particularly the Bronze one! I saw a few 454-Powered 3500’s in San Diego (yes, Corvette Rat motors in a British car!) and they were the equivalent of the Ford deuce coupes at the time, and they kept well… Where is that yard? I’m SERIOUSLY thinking about getting a “Diamond-in-the-rough” 3500 to resto-mod!

David, thank you for this. I cannot say if I’ve ever seen a Rover automobile of any variety from having lived in the Midwestern United States my entire life, but learning something new is always a good thing.

I love these. I would probably never dare buy one but one of these with a late V8 from a Range Rover and a five speed would be a pretty nice budget four-door Aston Martin.

This car’s story, while very interesting, seems to be the same as virtually every British sedan (saloon) ever brought to the U.S. market after WWII, with the exception of Jaguar and Rolls.

The looks of this car do absolutely nothing for me. I don’t think the car’s looks worked very well in 1980, either. Perhaps this would have been groundbreaking in 1968, but I believe that this car’s general look had grown stale by the time it made it here. The hot cars of 1980 were much more angular.

It was more like ten years ahead of its time, not behind. As in the aero-look mid-late eighties…

The SD1’s arrival in the US during the Great Brougham Epoch was not well timed, but in Europe, the SD1’s design was very well received, and furthered the march to the modern aerodynamic cars hence.

My admittedly American eyes see more than a bit of NSU Ro80 in this one, only as a hatchback. Put some stainless trim around the greenhouse on the Rover and you have a cutting-edge late 60s design. I freely admit that this was never a look that really called to me, so this style’s fans may look at this car with a better eye than I could bring.

As you say, that school of styling came back later in the 80s, only with more blackout trim. In either case, I would say that Rover missed the styling cycle by about 180 degrees. I guess too early or too late often brings the same result.

And admittedly, the SD1’s design impact would have been greater if it had arrived when it was originally intended to, in about 1974 or 1975. The development was protracted, to say the least. And the fact that the US version didn’t arrive until 1980 is of course a joke. By that time, it really wasn’t all that leading edge.

The Citroen GS pioneered a similar aerodynamic design, and it managed to arrive in 1970. Of course, the Citroen GS and Cx weren’t sold in the US, so for someone wanting an anti-brougham in the US, the SD1 was pretty much in a class of its own.

I like the SD1 too but I have to agree with JPC. it was at least 5 years too late, 10 in the NA market. It may have been a footnote in the trend towards aero, but I find it really hard to imagine its actual styling holding up in 1987 To me anyway, the SD1 always looked like a giant Chevy Monza hatch with 4 doors.

Not only that, but the rear 2/3rds of this car look strangely like a Chevrolet Citation four door hatch to me from the side profile view. The front clip is much different, but the main box is similar.

There was a company that federalized Citroen CX’s back when they were new. You can still find them on eBay regularly and I usually see one or two out on the streets per year. Even though Citroen never sold them here officially, it wouldn’t surprise me at all if more CX’s ended up being sold new in the US than Rover SD1’s – that’s pretty sad!

Yes, there used to be a couple floating around LA and SF I’d see. More sales than the SD1? Maybe, but I doubt it.

Another British Leyland dud which speeded up the demise of BL.Joe Lucas fuel injection meant that Rover drivers ended up burning shoe leather instead of rubber.Lucas fuel injection was a flop in the Triumph 2500 and Stag.A Rover SD1 was my Uncle Bill’s last British car,after numerous trips back to the dealer he bought a BMW 5 series can’t remember which one it was.

Nothing but a shipping crate for that fine Buick/Rover V8!

I suspect these will be bought for their V8s. Of course late model Land Rover V8 is probably a better deal in the long run.

I actually test-drove one of these new, off a dealer’s lot, around ’81 or so. Ordinarily it would have been out of my price range, but the dealer was offering a huge discount. When I got in and closed the door, and bits started falling out from behind the dash, I understood why. As I dimly recall, it drove quite nicely, but the appalling build quality and ;lack of durability was obvious. I eventually ended up with an Audi 4000 5 + 5 and was much the better for it.

Top Gear (UK) did a show “Remembering British Leyland” and one of the featured cars was a Rover SD-1.

http://tviv.org/Top_Gear/Season_10_Episode_7#Remembering_British_Leyland

The quality of the home-market SD-1 was just as bad as the exported versions.

Not only did interior and exterior bits fall of the car, but one of the read doors did as well.

Here is a link to the video of this test:

Obviously staged. Doors don’t just fall off. Top Gear is notorious for this kind of BS. Like staging collisions with vehicles that have engines removed.

Yeah, that doesn’t affect the crash dynamics much.

Most of the time, Clarkson is full of crap. I remember reading his stuff in CAR magazine in the 80s. Any articles pertaining to US cars that he wrote were full of gross inaccuracies and outright fabrications. One that really infuriated me was his reference to the original Pontiac Tempest as actually having ropes (as in hemp) for a driveshaft.

Obviously never ever even saw one. Another time, he wrote a piece on vintage Corvettes. Pointing out that the one in the photo had the legendary fuel injection when it was plain to see the good old round air cleaner atop the engine.

+1

Top Gear = carefully staged comedy

Because of the format, people tend to forget that it’s a scripted show…

You don’t watch Top Gear for any reasonable commentary on cars, you watch it to see the Three Stooges with an automotive bent. Great entertainment, laugh myself silly almost every episode, but for actual information Fifth Gear is much superior.

Do you mean to say that there are people out there who take Top Gear seriously? I don’t think they take themselves seriously, let alone expect us to. What would be the fun in that, anyways? I’m gonna enjoy the door falling off every time because it was dang funny!

Back in the early 1980’s when the show had the likes of William Woollard and Sue Baker it could actually be useful and informative.

The only similarity between that original format and the trash that it’s become today is the name.

Sounds to me you’re more of a Fifth Gear type of chap.

Clarkson has never been anyone that I could really admire, and I never read any of his old articles, but the fact that he got it so wrong does not amaze me in the least. He never let facts get in his way on TG. Think of it this way: if Clarkson was commenting on this site, he would be shouted down by commenters for his lack of honesty and integrity if writing such drivel

The issue with Top Gear of Clarkson/Hammond/May era is that they presented it as a car show and claimed to be “petrolheads” when they patently showed themselves to not be aficionados of cars. The problem is that many otherwise fine people thought otherwise, and that the show actually was informational about cars and driving. As a result, we have thousands of people all over the world who think an idiot power-sliding an overpriced unicorn of an exotic around a private track after purposely destroying some poor older common car is an expert on automobilia. How can you justify you love something and then “repair” it by bashing it with a hammer? Or crashing into your fellow driver just for a lark? I love something, so I must destroy it? Really? Any actual good that may have come out of that show was wasted on the buffoonery committed by the triumvirate of fools. That they were “hoisted on their own petards” with the Clarkson slap fest over a catering truck order was kharmic, but those who loved the hosts loved them unconditionally, and Amazon is wise to spend a few of its pennies sopping up the eyeballs of those who enjoy that style of entertainment.

A college friend had a 3500… Seemed he was always repairing something expensive. Was quirky/different, though. I liked it.

These were rare as hen’s teeth in Virginia, but my sister once went out on a date with a guy who drove one. I was driving a ’63 Skylark with that same 215 V8, which made me inclined to like the car. The styling worked for me; that plus the rarity made this seem like the coolest wheels possible.

Sadly, my sister didn’t like the driver as much as I liked the car, so there was no second date, and I never saw the car again. In fact, I don’t think I ever saw one on the road again.

If one could be found in decent enough shape id take it… It would also need to be cheap(damn near free). then id remove the rover lump and put in a 5.3 ls based truck engine and a T-5 manual,tear out every trace of electrical and start with an isis multiplex electrical system. replace the dash with a custom built but similar looking fibreglass one, redo the rest of the interior and body and drive it. after untold thousands of dollars to correct rovers shortcoming I would have a reliable one. Also I like these but hate massive quality and materials issues they have.

Both were quite rough unfortunately. Especially the interiors. Add in some rust and the shot rubber bits from sitting so long and it would be a long road to get it back to drivable. If they were a little better I might have been tempted too.

There was a clean engine-less one of these on ebay about a year or so ago, and that was my though too, I wonder how hard it would be to slip a GTO LS2 with a 6 speed in one of these and create what could be an epic sleeper.

When I was a kid these were plentiful and I really loved ’em…right now I can’t remember the last time I’ve saw one…I’ll always associate this car with this song http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uPudE8nDog0

Oddly enough, when we visited Austria in 1981, these were surprisingly common there, although almost exclusively six cylinder version. Austria had not joined the EU yet, and a favorable trade relationship with GB made the SD1 a hot executive car. It was probably the most surprising automotive aspect of that trip. I suspect most of the Rover drivers ended up in BMWs the next time around.

It is pretty fitting to see the SD1 at the wreckers, it would have saved a lot of time and money to just drive straight from the dealership to the scrap yard.

Growing up on Vancouver Island, quite a few of the Pseudo-Brits (yes, we actually had Canadians who pretended to be Kippers, right down the the affected accents) rose to the occasion of Queen and Empire and bought them. I personally knew two and the cars were bone fide absolute disasters, the worst cars I can ever remember. One man I knew quite well, he paid something like $15,000 for the car ( a fortune at the time) waited for six months to get it and then when he got it, the car didn’t actually run. The dealer, a really professional organisation that was located on a side street in an old barn, didn’t have the slightest idea what to do about it.

Eventually they got the car running but it was one disaster after another. Finally, after a grand total of three years, he scrapped the car and he became a dispossessed, hang-dog Pseudo-Brit. Never got a lecture about the wonders of Merry Olde again!

The SD1 was a very appealing idea: a modern aerodynamic design, fairly straight-forward suspension, a US-style V8, and a chic interior. If it had been built by someone else (Ford? or?) I could have very much seen myself behind its steering wheel. Of course, headlight covers would have been a necessity; the US-mandated front end was an atrocious necessity.

Ford did offer a “modern aerodynamic design” with a “chic interior” in the late 1980s with the Merkur Scorpio.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merkur_Scorpio

In some ways that is a the European version of the Mercury Sable but with a hatchback and rear-wheel drive.

I drove this car in Europe (UK and Germany) and was quite impressed. The version that we got in the US was a bit under-powered, but very comfortable.

We did a CC on that: https://www.curbsideclassic.com/curbside-classics-american/curbside-classic-1988-merkur-ford-scorpio-nice-landing-wrong-airport/

Paul Niedermeyer’s “Curbside Classic: 1987 Sterling 825 SL – Turkey In The Grass” from NOV 26, 2011, is a great companion piece to this article.

https://www.curbsideclassic.com/curbside-classics-european/curbside-classic-1987-sterling-825-sl-turkey-in-the-grass/

The 1987 Sterling offered a similar design to the Rover SD-1, but based on a Japanese (Honda) platform. Better build quality than the original SD-1, but still not good enough to succeed in the US market.

Here is a picture of a Sterling hatchback.

While strolling around downtown Fort Collins last summer, there was a gentleman whom had set up a sort of classic iron kiosk in his backyard (Home Depot shed, party tent, table with refreshments). On offer? A pristine SD1, along with a gaggle of clean UJMs. Upon hearing my breathless jabbering about the odds of finding one in such a state at this late date, the missus smiled, nodded politely…and firmly led me away by the arm.

i always like these. a lot.

there is an excellent in depth write up on these here: http://www.aronline.co.uk/blogs/cars/rover/sd1-rover/the-cars-rover-sd1-development-history/

Yikes but that american market front end is ugly! Astonishing how easily ruined a handsome car can be just by giving it goofy headlights and a comedy under-bite for a front bumper…

I’ve always had a huge soft spot for these in the domestic market form I grew up with. Even back then I understood they weren’t the best built or most reliable but there’s something about them that always makes me smile.

Back in middle school a favourite teacher drove a (then) newish metallic blue 3500 with the lovely lovely V8 and most of the bells and whistles. She drove it fast too from memory: a bunch of us forgot our kit for swimming one week and were herded into the beige velour interior of this beast and flown around the neighbourhood in it to collect our missing trunks and towels.

The overwhelming impression the Rover left me with was of a kind of quiet confidence and speed.

Rationally I know that (like all BL products of the time) they were shoddily built in the gaps between strikes by disgruntled trotskyist malcontents. I know that you’d be lucky to find one that had only been poorly built, rather than actively sabotaged. And I know that owning one would be a deeply disappointing, frustrating and expensive experience, and yet on the rare occasion I still see one, they never fail to make me smile.

I’ve only ever seen a couple of these things and then I can’t say how long ago it’s been. But, they’ve always appealed to me. There’s something about a four door hatchback (especially one styled kind of like a Ferrari Daytona) with a V8 drivetrain that appeals to both sides of my brain. I like the utility, and I like the idea I can outrun most everything, too.

I guess that was the reason why I liked the Pontiac Rageous show car from about 15 or so years ago. A four door Trans Am with a hatchback really appeals to me.

This car, apparently was not any of those things. Nor was the follow up Sterling hatch either. But in a real funky, international kind of 70’s way, these were really neat cars. Too bad they never worked out.

There are plenty of Rovers locally I shot some for the cohort Running examples are harder to find. I nearly bought one in Sydney years ago it was a Vittesse 5 speed with injection. A quick phone call to my BIL who worked at Parnell Rover City as parts manager killed that idea the parts and Id need them posted from NZ where all the new parts are were a horrendous price. The V8 Rover engine is great these thing beat all comers in the European touring car races yes all the german garbage too. Its all the periphery parts that fail like electronic hatch locks @$500 at time nar not this black duck I stayed driving my 63 EH another couple of years. The P6 was a better car

These were sold for quite a few years more here in Aus, but I don’t think I’ve seen one for years. I’m sure there’s some guy in one of the outer suburbs with a paddock of non-running examples. Which reminds me, i need to find that guy who collects Citroens! Amazing catch, by the way! And a very detailed article, it felt like I was reading AROnline. Such a shame British reliability and build quality torpedoed this and the Triumph TR7/8 and the funky Princess.

Be thankful Australia was spared the Princess horrible build quality even for BL after the P76 debacle BL Australia was scared of releasing untried lemons and that Rover is very P76 in its underpinnings

I’ve told this story before, in the context of the P6 CC…I used to see one of these on occasion, in Nashville of all places, at youth soccer games probably 30 years ago. I think the owners were either British expats or just into unusual cars. That remains the only one I’ve ever seen.

I used to occasionally see a 3500 up the street from my parents’ house in the early ’80’s. I loved the look of the car, but I’d always heard scary stories about British cars and their numerous issues, mainly electrical problems. Still, it was about the same size (and similar styling) as our ’78 Gutless Cutlass, and the 3.5 V8 would have fit nicely under the hood. Midnight engine swap, anyone?. It would have been a win-win situation. The owner of the Rover would have got themselves a slower (but reliable) 3.8 V6 engine, and we would have had a better performing car with better build quality…and considering the quality of our Gutless, that’s saying a lot.

I have always loved the profile of the Rover. When Honda came out with teaser photos of the Crosstour, I got excited and thought for a bit that they were going to re-boot this exterior design, as a mid-grade 4dr hatch. But then the actual car debuted, all jacked up, Joker-grilled and lumpy-fendered. Big sigh-epic fail!

…the V8 was eventually fitted with Lucas L-Jetronic fuel injection.

I kind of like these cars, and remember when they were semi-plentiful. But having your engine’s FI system made by The Prince of Darkness — what a terrifying prospect!

A four-barrel Holley carburetor, which reduced servicing headaches and boosted power, was quite a popular swap for these.

Yeah, I’ll bet it was.

I think these are so unbelievably cool… wish they had started a trend of large, RWD, V8 powered hatchbacks. I can’t ever remember seeing one moving under it’s own power, the few I’ve come across were in similar shape to these.

I believe all of these Rovers, the P6, SD1 and Sterling were fundamentally good cars, spoilt, to varying degrees by poor manufacture. However the P6, Sterling and even the SD1 were made in substantial numbers and were well regarded here in the UK. The SD1 eventually became a reliable car with much improved build quality by the late ’80s. Of course by then damage to MG-Rovers name had been done. As in most cases the gap between good and bad cars wasn’t as great or as clear cut as is made out today.

Im not sure that any British or French cars would have sold well in the US at that time, the gulf between Europe and America in terms of expectations of comfort, styling and economics were so great. Plus the desire to buy US built products was and is much stronger in America than in Europe.

America really wanted to like Jaguars, but the ownership experience was horrible.

America bought the Americanized Renault R9 (Alliance), but they became poison because of reliability.

My uncle was one of the 480 Americans in 1980 to have purchased one. He said he really liked it but sold it to a Rover enthusiast in 1990 for $75.00. It was always in the shop and he would have to wait months for parts. Bought a Benz to replace it and has put almost 400k on that S-class.

Commie stricking British car workers! No bad management and lack of investment killed

BL cars at the time. Dad was a industrial adhesives salesman to the auto industry. He would work on a project for months and just as it went to production… ” We scraped the idea Geoff ,we are going on to something else”.

Early SD1 had dirt in the paint finish because the booth fans were wired up the wrong way round. The blow instead of sucked!

Aged 26 I drove a silver 83 3500 Vanden Plas . Twin carbs and the GM400 trans. The american made cruise control worked once!. At 100mph the front end got so light it was like playing a video game.. no feel at all. Sold it after 2 years and took a £500 hit.

Such pretty, pretty cars, especially in facelift form with the properly-flush headlamps, deeper rear hatch window and updgraded dashboard. We got the 6-cylinder and V8 models new here. A top-spec facelift V8 is on my top-10 list of classic cars to own one day – yes, even though I know the electrics would likely be quirky it’s be worth it to look at that beauty while waiting for the breakdown truck.

@Mark Hobbs- At 100mph the front end of any car will get light unless it has a front spoiler. I’ve been at high speed (not giving any more details) in a few ’70s cars- all, especially those without power steering got frighteningly light. Later SD1s did have spoilers front and back, no doubt to control high speed issues.

I’m obviously a curmudgeon – after the P5 there were no more ‘real’ Rovers (i.e. elegant tanks). The rear view of the SD1 reminds me of a Chevy Citation.

Intersting comment about real Rovers because all my favourites are P5 onwards – P6 and SD1 because their designs looked fresh, there was a good deal of design innovation going on in their development and in the same period interesting, but not commercially successful, use of gas turbines.

Clearly the 200/400600/800 etc. are Honda collaborations and would agree with you in that instance.

British Leyland commercial, featuring the 3500 at the end:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mr2Wa4i1vVw

(The commercial made BL sound a whole lot better than was the reality at the time!)

Saw a 2600 Rover yesterday that engine was supposedly lifted straight from the awful P76 Ive driven a 6cylinder P76 I know why they stopped selling them.

That SD1 would be South African if it had the P76’s E-Series 2600. The E-Series 2600 was only ever built in Australia (never UK) and after Leyland Aussie closed, the tooling was then moved to South Africa for the South African market SD1.

The SD1 2600 in the rest of the world (including NZ) had the unrelated six with that started out as a revised version of the Triumph 2.5. There was also a 2300 version of that engine, but both ended up as orphans.

The South African SD1 2600 was E-Series 2622cc, OHV and had 95hp; the rest of the world’s SD1 2600 was 2597cc, OHC and had 136hp.

As always, lots of interesting detail at the fantastic aronline website. http://www.aronline.co.uk/blogs/cars/rover/sd1-rover/engines-rover-sd1-six/

Jeez, that USA only 4 headlight nose is an horror. Oh the sheer uglyness of it!.

Over all I like the shape of the carm but the poor detail design kills it for me.

I had a 3500 sdi s reg when I was sationed at raf Bentwaters My kids like it when I painted it red so we had a red rover.I loved that car going under the under pass by the Ipswitich train station, it sounded so cool!!! I have been looking for a sedan to play with though the us verson did not look wright may be I could send for uk frount since that is what I’am use to. People think I’am a nut (nuter) because I told them I can drive right hand drive.I saw a new rover in 1983 at the dealer in moon raker blue. The two cars that are on this web site does any one know if they are still there?Or were they are? I’am just east of Atlanta ga. I do miss the uk, my first son was born there.

Where is the yard where these rovers are kept, I might be interested in getting one to restore

Unless these were/are owned by an enthusiast stockpiling parts cars I’d imagine they’re long shipped to China as shredded or cubed steel- the original article posted about 4 years ago…nifty to see old Brit iron from the swinging 70s though!

Please do not say that!!! I to would like to find them and see if one good one can be put together!!!

Man. Too bad that we’re already on Thursday. Otherwise this would mean a Rover/BL week. If I was ready to contribute with articles I would have gladly written an article on the Rover 200/25, as I kind of like them (HGF aside)

I only Knew of the existence of the SD1 when I saw one 4 years ago with no wheels being carried in the bed of a ’90s Toyota Dyna. It had the 2.0 liter.

There’s a silver SD1 just round the corner from me here in Glasgow. Guy uses it every day.

I’ve only ever seen two of these in the wild, both in the early ’80s. About 16 years ago saw one (and sat inside!) at a British car show I went to.

Weird lack of any driver’s-side air vents.

There was some speculation that Rover (then owned by BMW) might bring the ’99/’00 Rover 75 to the US, but it never happened. I really liked that car’s styling inside and out (the dash was clearly modeled on both the P6 and SD1).

I think there was even a pic of one with side markers in the front tip of the chrome side trim.

An early Rover press release for the 75 noted that it was designed with federalization in mind for potential US and Canadian sales even though they weren’t currently selling in those markets. Americans never got a 75, but Brits eventually got a 75 with a Ford Mustang V8. With rear wheel drive! I can’t think of another car that was offered in both FWD and RWD configurations. Only ones that come close are the previous-generation Transit van, that rally version of the Renault 5 with rear or mid engine (can’t remember) and RWD, and those RWD cars based on the ’30s Cord after they failed, but those were made by other companies.

Wow, the Pininfarina 1800 is now 50 years old. Still looks like the future to me.

We had a P6 3500 at home when I was growing up, followed by an SD1. The P6 was the nicer car, though rear room and boot (trunk) space was pitiful. The SD1 rectified these problems but, reliability issues aside, always felt a bit more agricultural – though I was only a passenger, never the driver.

Correct me if I am mistaken, but wasn’t Rover the descendant of the defunct Alvis Motoring company? What a comedown from the glory days, To think, how close Rover came to hitting a home run with the 3500…yet managed to cut every corner possible and muck it all up. I remember when this car first came out, and the Big 3 American car mags all gushed over it for about a month or two. Then, the doors blew in.

Never saw one of these in the wild “back in the day,” largely because (a) I was a high school kid with zero interest in automobiles and (b) British cars of any stripe, except for the TR7, were danged scarce in my Midwest factory town. Later, when I became a raving Brit car geek – owned a TR7 and a TR8 simultaneously at one point – the Rover 3500 piqued my interest because it had my TR8’s engine and 5-speed gearbox. Also, I finally saw one in person – ill-fitting doors, window trim, body panels, and bits hanging slightly loose – at the big British Car Union in the Chicago ’burbs in the mid-90s.

There’s a good YouTube series with a couple of British guys restoring a first series 3500. Man, those things rusted to crap! (Not just the usual places, but odd stuff like the steel sun roof – rusted itself shut on this example.) The guys had to do the classic British fix of cutting out the rotted metal and welding in sheet steel replacements – sheesh! what a lot of work!

But…

For my money, the SD1 is one of the most aesthetically pleasing cars of all time – one of the few sedan-only cars that don’t prompt me to lament the lack of a coupe. (OK, the Jag XJ6/8/12 series is the other….) Why? Jeez, dunno. I like the SD1’s crisp lines well-defined lines, but it’s also not edgy and boxy. (The all-time most aesthetically perfect automobile of all time, ever? The Triumph TR7/8. Just so you know my biases…..)

Brit cars: you love ’em for the cars they could have/should have been – maybe sometimes were when they were running. Then the repair bills start mounting up, and the endless rounds of, “OK, this is gonna cost a lot to fix but once it’s done the car’ll be sound and I’ll only have to pay for routine maintenance.” Only…that first major thing you had to fix had, by then, worn out, and the cycle starts all over.

I always say the British makers could afford to either build cars or design new ones. They just didn’t have the capital to do both at once.

I have had a 1970 3500s, and a 1980 3500 sd1. I must have been lucky, because I never had a problem. Great cars, lots of fun to drive. I still have a 1970 3500s, it needs some engine work, I will get it fixed, and keep enjoying it. I would love to know where this “storage yard” is, I would see about buying the 3500 sd1’s.

The Citroen CX and the Rover SD1 are some of the only cars designed in the 1970’s that have enduring appeal to me, and they have similar design features.

The Citroen was only available in the U.S. grey-market and the SD1, well, it might as well have been.

I imagine keeping either one of these running in the U.S. would be a nigh-impossible task, better left to Quixote.

One has to wonder what the ultimate goals of both labor and management were, given the appalling lack of quality, frequent strikes, and management malfeasance at British Leyland. I don’t think either of them really wanted the entire enterprise of British automaking to continue.

To not get stuck with the cheque, mainly. Management was dealing with an impossible set of political imperatives, an unwieldy set of frequently antiquated facilities spread all over the country, and a mess of different brands and organizations that had in some cases been fierce competitors not that long before and were still not necessarily convinced they weren’t. This was in addition to ineptitude, malfeasance, and an inability to wrap their heads around the big picture.

Labor was dealing with inadequate facilities — some Dickensian, some just badly organized and run; a very painful transition from piecework to hourly pay; some longstanding occupational divisions that didn’t always make sense for the nature of modern automotive manufacturing; management that the unions felt (sometimes with considerable justification) couldn’t be trusted to keep any agreement they made and was happy to bolster their own positions at the expense of the workforce; an increasingly unwinnable political situation; and a popular and business press that was resolutely determined to attribute the problems of industry to the inadequacies of the British worker and what Mark Knopfler pithily dubbed “Industrial Disease,” whether or not that reflected the facts.

I don’t think most of those involved wanted to collapse the British auto industry, but at the same time I don’t think anyone involved at any level had any clear conception of what a successful, healthy version of that industry ought to look like or how that would be achieved if they did.

There was one in my neighborhood back in the early-mid 80’s. It must have come from the British Leyland dealer that was in Culver City. A 3500 was featured in a short-lived TV show titled ‘Tenspeed And Brownshoe’, starring Ben Vereen and Jeff Goldblum. The show was created by Stephen Cannell and directed by Juanita Bartlett (both from the Rockford Files), you would have thought with talent like that it would have done better. Maybe they should have used a Firebird….

One of my early-gradeschool classmates lived in a nearby subdivision—one of those given a ritzy name (“Cherrydale”) by its original developers and Realtors™ to dazzle buyers out of perceiving the actual quality of the big houses.

I guess it’s fitting, then, that my classmate’s mother drove one of these. I have no idea why I would have ever got a ride with Mrs. Black, for I didn’t really associate with her daughter; perhaps it was a field trip kind of thing. I’d never seen a car that looked quite like it; I asked what kind it was and Mrs. Black said “Rover”. That’s the beginning and end of what I know on the subject.