(first posted 11/13/2017) Darlene Dorgan was a 5′-2″ tall, 110 lb. spark plug of a girl who graduated from Bradford (Illinois) High School in 1930. Although she wanted badly to go on to college and study physical education, her father Bill, who ran an ice cream parlor in town, desired her to stay at home, working as a beautician as her older sister had done. While she would have certainly complied with his wishes, he did offer to buy her an automobile as an additional enticement to not go off to college. A used 1931 Ford Model A was subsequently purchased in 1933, which Darlene likely drove the 35-40 miles into Peoria for the last of her beauty school lessons.

The smart-looking Ford expanded her world beyond the small town of Bradford, so imagine her surprise (and anger) when she noticed the car missing from the driveway one afternoon…

Her father, town jokester and always the businessman and horse trader, had sold the car on the spot to a passerby who expressed interest in it, without consulting his daughter on the matter. Darlene was fit to be tied – a reaction, perhaps, her father had not fully reckoned on. A replacement was hastily purchased, but rather than the handsome Model A, a somewhat tired and out-of-fashion 1926 Model T Touring Car now stood in the driveway. It represented the penultimate production year of the automobile that arguably had as great an impact on society as any other 20th century invention.

When Henry Ford introduced the Model T in 1908, there were only a few hundred miles of surfaced roads in the United States, a distance that could be traveled in less than five hours at the Model T’s comfortable cruising speed of 35mph. Less than ten years prior, there were only ten miles of surfaced roads for the few thousand automobiles then in use, with around 93% of roads being unimproved at all. “Surfaced” at that time might mean nothing more than some gravel spread on an old cowpath and one was far more likely, especially in rural areas, to find badly rutted dirt roads that turned quagmire in rain.

These conditions were difficult enough for horses and wagons, so to be competitive, fledgling automobiles had to be designed to sit high and have a great deal of articulation and flexibility.

“I will build a car for the great multitude. It will be large enough for the family, but small enough for the individual to run and care for. It will be constructed of the best materials, by the best men to be hired, after the simplest designs that modern engineering can devise. But it will be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one – and enjoy with his family the blessing of hours of pleasure in God’s great open spaces.”

~ Henry Ford in 1908

Henry aimed to expand the horizons of the common man with his ‘universal car.’ The rural farmer of 1908 had likely been no farther from his farm than the 10-12 miles his horses could carry him in a day and still get back in good shape. The Model T enlarged this circle to the point where one farmer was quoted as saying he could “call on friends living thirty miles away who had been asking me to come for twenty years.”

By the year 2014, there were 797 motor vehicles per 1,000 persons in the United States. In 1908, however, there were around 8,000 cars for a population of ~90 million, or roughly one-twelfth of a car per 1,000 persons. Automobile production increased so quickly in the ‘teens, that before 1915 it was unusual if you owned an auto, and by 1925 it was unusual if you didn’t. Acknowledging the rapid impact on society, a study published in the 1920s by Robert and Helen Lynd noted with concern that the automobile was a threat to church attendance because of the new habit of taking a Sunday drive. Vacations by car also became popular during this time.

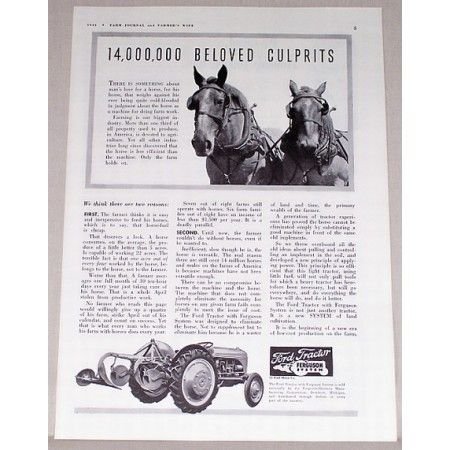

Although towns like Bradford generally did have electricity by the 1930s, only 13% of rural farms were connected, and one as often as not would meet a horse-drawn conveyance on rural roads as they would an automobile. It wasn’t until the late 1930s and 1940s that rural farmers would begin switching over to tractors in larger numbers and in fact, Ford’s N Series tractor introduced in 1939 was aimed specifically at replacing a team of horses.

The Model T was introduced at a price of $850, which by 1925 had dropped to under $300 for a “base” five seat Touring Car. Women were not-uncommon targets of marketing, and the rapidly-increasing numbers of automobiles created new business opportunities for their sales and maintenance. Motorcars also enabled rural folk to have better access to the city, even as city folk began moving out to the suburbs. When one rural farmer’s wife was asked why her family had an automobile but no indoor plumbing, she quipped, “Why, you can’t go to town in a bathtub.”

Ford’s ‘Flivver’ was powered by a 177 c.i.d. (2.9l) flathead four-cylinder monobloc gasoline engine developing 20hp and 83 ft. lbs of torque at 900 RPM. Power – such as it was, but ample for the day – made its way to the rear wheels through a planetary gear transmission with two forward gears, one reverse gear, and a very non-standard (to us ‘Moderns’) array of pedals on the floorboard. Throttle was controlled, along with spark advance, by levers off the steering column, which was mounted to the left (“near side” to someone used to driving a team of horses), a departure from the more common right-hand drive (“off side”) setup that allowed the driver to better see and stay out of the ditch. Ford was thinking ahead to the day when there would be so many cars on the road that the driver would need to better see (and avoid) oncoming traffic. Interestingly, the Model T engine was used in a number of non-automotive applications and was produced through 1941 – fourteen years after manufacture of the car ceased and a total of exactly 12,000 days of engine production.

While there are accounts of automobiles from this period lasting well over 100,000 miles, the far more typical lifespan was 50,000 miles or less, especially for rural cars that lived their lives in mud and dust (the Model T had no factory air filter). Maintenance on the roughly 1,481 parts (give or take) that made up the T included items that were serviced daily, every 50 miles, every 100 miles, etc.. If you drove a long distance in one trip, you simply stopped and did the 50 mile service every 50 miles or so. A ‘ring and valve job’ was typically required every 5,000-10,000 miles.

In the 1970s, Les Henry, former curator of the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, MI, calculated there were a total of 15,766,539 Model T engine serial numbers assigned (some percentage of those were spares not installed in ex-factory cars), and maybe 2% of cars survived to that day (which would still be some 316,000 units!). Surviving Model Ts today are driven lightly in much cleaner conditions and it’s not uncommon for an engine to run out 50,000 miles before needing an overhaul.

By the mid-1920s, the Tin Lizzie was firmly established in Americana, and was often given a pet name by the owning family. A trend developed among the college-aged to paint various funny phrases and expressions on older cars, which became known as “Lizzie Labeling.”

Ford’s car was also starting to experience competition from competitors who offered more in the way of creature comforts as well as power and style. Concessions were made to market pressure, so that by the time Darlene’s Model T was built in 1926, it had an opening left-side driver’s door (finally!) as well as an optional electric starter and demountable wheels.

Note also that Ford bodies have been entirely redesigned for greater comfort, convenience and added beauty. Yet it important to remember that these cars are in no sense NEW cars. It is advisable to avoid using the word “NEW” in discussing them. The word “NEW” implies a redesigning of the chassis as well as the body. While it is true that certain refinements have been added to the chassis and that these are more radical and therefore more conspicuous than any which have heretofore been made, the Model T chassis (though lower) remains the same in design and construction as it has been since 1908. It is the same Ford car, now as always noted for economy, performance and reliability; only the bodies have been redesigned. Do not forget this point and do not fail to stress it in talking to prospective car owners. It is a strong selling point.

In this Sales Booklet text for 1926, Ford was very careful to not call the 1926 model “new.” In fact, the ‘improved’ T still looked dated, and more than passingly resembled the Chevrolet of 1923.

Colors were another big change for 1926; one could purchase a Fordor Sedan in “Windsor Maroon” or a Coupe or Tudor Sedan in “Channel Green,” with the Touring Cars and Runabouts still offered in your choice of “Black.” More colors would be available after late 1926, and Black was no longer listed as an option for any Model T. It’s a rabbit hole, but much more information on the Model T changes for 1926-27 can be perused over at the Model T Ford Club of America site.

Getting back to Darlene, she had quite an adjustment to make from the Model A, especially in the operation of the transmission. But mastering the Model T, downgrade as it was, meant independence – and the opportunity to get away from the heat and humidity of Midwest summers for a few days of vacation. By the summer of 1934, the tension in the Dorgan home had subsided and Darlene began planning just such a trip with a few of her friends. The car by this time had already been repainted silver (with hand brushes!), and the spare tire cover declared “One More Payment And She’s Ares.” [sic]

Her first ‘auto camping trip’ was planned for July, 1934, and included four other girls. Darlene, 24 at this time, would be the sole driver on this trip. Her sister Verna was 22, and the other three girls ranged from 21 to 18 years of age. The Model T seated five and had no trunk, so the girl’s luggage would ride on the running boards. In that day and age, it was not only unusual, but was also borderline unacceptable for young ladies to travel unaccompanied on a long trip like this. Darlene established the rule that no smoking or drinking was allowed on the trips so as not to give the wrong impression to anyone, and while there was the exciting prospect of meeting boys their ages on the trip, they considered themselves to have ‘safety in numbers,’ with little concern of any trouble arising (times were different!).

The destination for the trip was Devils Lake in Wisconsin, a distance of over 200 miles from Bradford, and which in a modern car on modern roads could be covered in four or five hours and on one tank of gasoline. In 1934, with a speed averaging 35–40 mph, plus stops for food, oil, water and fuel (and assuming no mechanical breakdowns or flat tires), it likely took the girls closer to twelve hours to arrive.

Emboldened by their uneventful drive up to the lake, Darlene on her way home diverted the girls to Madison, WI to tour the State Capital, and then right into downtown Chicago to visit the “Century of Progress” World’s Fair. They would read in the next day’s newspaper that John Dillinger had been gunned down as he exited the Biograph Theater, at approximately the same time the girls had been driving near the theater the night previous. Darlene and the girls would return home very late on July 22 or 23, tired, but full of happy memories.

This would be the first of eight trips taken in the Model T over a nine year span. Nineteen of Darlene’s friends would accompany her on these cross-country jaunts, at a time when girls traveling unchaperoned raised eyebrows. The Silver Streak was already an ‘old’ car by 1934, and Darlene would quickly set her sights on destinations much farther away than the Wisconsin Dells! Join us tomorrow for Part II to see where the girls will head, and whether the Silver Streak can get them there!

Note: The author does not purport to be an expert on the Model T, perhaps the most written-about automobile of all time. Gentle corrections to any erroneous information are welcome in the comments!

Very fascinating article! What struck me the most was how much planning went into the road trips and how long it took to go ‘short distances’ in the 1930s as compared to today.

I remember doing the road trip in eastern Germany a few years ago, visiting places where my mum lived before fleeing to West Germany in 1953. At one point, I drove from Vierraden where her mother owned a tobacco farm to Gielow where she and her family took refuge from the advancing Soviet army during early 1945.

The distance between Vierraden and Gielow was about 150 km and took almost two hours with a car today. I had a navigation app, leading the way through many turns and twists effortlessly.

After I finished this leg, I was very much overwhelmed by the thought how hard it was for my mother and her family to travel through the war-torn landscapes. No navigation aids such as maps or road signage to help them. No information about the road conditions ahead of them. They relied on the local people to give them the directions and the shelter at night. It took them about three weeks and lot of effort to cover 150 km on foot and wagons pulled by horses.

I found it interesting my first trip to Germany that roads were named by their endpoint city names. We have a few around here that are the same (at least colloquially), such as “Princeville-Jubilee Road.”

It was confusing at first, but made sense after a bit, especially to someone not familiar with the area.

My Father made a film for Ford’s 50th Anniversary called “The American Road” and said he was amazed how easy it was to fix and keep running all the Model T’s they had to resurrect for the film.

Very cool. Ease of repair was no doubt a major factor in the T’s popularity. Once you got into rural America, I’d imagine the local “machinist” of that era was most likely a blacksmith!

It’s been written that this ability to improvise – required in the early days of the American automobile – later gave the U.S. military an edge in combat. The skill of keeping machines rolling with limited resources was a talent that was not uncommon among the troops.

You want military field improvisation? Read Ike’s log of the 1st transcontinental military convoy in 1919. They even brought along a portable machine-shop. Fascinating reading if you’re a gearhead or amateur historian like me:

https://www.eisenhower.archives.gov/research/online_documents/1919_convoy/daily_log.pdf

This is the world the Model T had to operate in.

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0268138/

My grandmother, two sisters & a friend drove from Chicago to Florida & back in 1930.

I haven’t been able to identify the car, but it is clearly nicer than a Model T touring. Still must have been quite the adventure.

Dan that car is a real puzzler. Not many had side louvers that close to the side hinge. And three door hinges. They could not have picked a worse angle for that picture for our purposes.

I was thinking Durant, they had three hinges but the window opening corners are too square on this car.

And those louvers!

This 24 Cadillac is very close, but I’m still not convinced.

Man, this is a rabbit hole! I see some resemblance to Chryslers and Plymouths from the mid-late 1920s, but nothing that’s an exact match.

I posted it on aaca, maybe someone will know what it is there.

This 1923 chandler looks like a good match

https://assets.hemmings.com/story_image/206091-1000-0.jpg

By jove, I think you’ve got it! Here’s a 1924:

Ed, this is great and you’ve got me eager to read more.

This article is also a great reminder on travel; I’m making a trip to Kansas City today, a distance roughly the same as Darlene traveled to go to Wisconsin. It’ll be a day trip when once upon a time, going that far would be the trip of a lifetime for many.

I’ve got a reprint of a 1927 Sears catalog that has lots of Ford parts. On page 1035 is the “Special Painting Outfit for Ford. Furnished in black only. We furnish enough material to finish the body and fenders of a Ford car, two coats, the top, seats, and engine, one coat.” Illustrated are various cans, brushes, and steel wool. Shipping weight, 14 lbs. Price…$2.85. For $4.45, you could get a kit for all cars with your choice of eight colors, including vermilion! Alas, no silver.

Great job of setting the automotive stage, so to speak.

Hard for us who take automobiles for granted to imagine how small the radius of a typical person’s life was at the turn of the last century. And how Henry envisioned bringing us closer together, but it had the unintended consequence of making it easier for us to be farther apart.

I’m glad I wasn’t in the room when Darlene found out her Model A was gone…

I’ve read a few articles from enthusiast in the United Kingdom about this legendary car. Apparently the engines were so simple that there were only about seven moving parts within the engine block. They were so well made that keeping a lizzy running is a piece of cake.

I want one!

Wonderful article Ed; thank you.

Excellent article!

My mom learned to drive in a Model T. In one legendary incident in family lore, mom slammed on the brakes and her little sister went right through the windshield! My aunt still has a nice scar on her head as a memento.

A fellow I know has an early 20’s Model T. Sitting in the drivers seat requires you to be small.

A fellow I know has an early 20’s Model T. Sitting in the drivers seat requires you to be small.

Indeed. No tilt/telescope steering column, no seat adjustment. The guy behind the wheel is about my size, 6′. Look where his knees are. It’s like an adult driving a kiddie car at an amusement park.

People were shorter then, right? (c:

People were shorter then, right? (c:

Yup, on average. My Grandfather probably fit just fine in his T.

Too bad that Aaron isn’t posting on Curbside anymore. He took the Gilmore’s Model T driving course in 2016. It being a nice day and I had nothing else going on, I met him over there and took a few pix. He asked that I not splash pix of him all over the net, so here’s a pic of the Gilmore’s teaching aid instead.

They have a Plexiglas panel on the transmission, so the insides are visible.

Now that’s cool. I presume it’s a ’26-27 given the cowl and timer placement?

Now that’s cool. I presume it’s a ’26-27 given the cowl and timer placement?

I have no idea, as I’m not that conversant on the T. It’s clearly a later radiator, and not nickel plated. Seems like all the 27s I see have nickel plated radiators.so from some time in the 20s before 27, with the paint removed.

Of course, that trainer could be something the Gilmore banged together from spare parts.

Ed, thanks for giving us this article. I look forward to the next road trips made by Darlene.

Apologies for removing your comment, Steve, but you’re getting ahead of the story, and I’d prefer “no spoilers.” Thx – Ed.

Great story, Ed! There is something about the Model T that really captivates my imagination. That thing would have been simply ancient by 1934, but they were so simple, durable and fixable that there were still gobs of them on the road then.

It is easy to forget that in 1908 it was the best automotive value on the market. It was small and relatively inexpensive, but it performed quite well in comparison with most cars costing much more. It was only in the 20s that it became a “cheap car” which required performance tradeoffs in exchange for the low price.

I look forward to reading more about Darlene’s story!

That thing would have been simply ancient by 1934, but they were so simple, durable and fixable that there were still gobs of them on the road then.

Ever ride in a T? I mooched a ride in one of the Gilmore’s Ts last summer. The engine is bolted directly to the frame, so it felt like someone was under the car using a jackhammer on the floor.

Yes, and a Model A’s engine was mounted the same way. Those big 4s were good at making vibration. Which is why Plymouth’s “Floating Power” rubber-isolated engine mounts were such a big deal.

Wonderful story! Look forward to next installment!

Awesome story. Can’t wait for the next chapter!

Here in SoCal, there’s a rather eccentric old man who routinely shows up at Bob’s Big Boy in Burbank driving a rusty Model T pieced together from scattered parts he scrounged up. It still sports “Horseless Carriage” plates and a functional “oogah” horn. He sits on bare seat springs while driving it, but doesn’t feel a thing. The only modern upgrades he’s made are Stewart-Warner gauges and a 12V electrical system.

Terrific story, excellently written. Awaiting part 2 eagerly.

Three pedals down main street .

Thanx for this informative article .

-Nate

As to T production numbers, more or less 15 million, of course.

But per day, the top number usually cited is 9,000 Ts built in a day. It’s not exactly clear how the score was tallied, maybe the radiator caps were left off of a week’s production to finish those cars all on count day? LOL

Think about that number…

That’s a lot of about anything in a day – without a single computer. 🙂

If it hasn’t been stolen for scrap, there should still be a commemorative plaque at the Highland Park plant giving a nod to the feat.

they considered themselves to have ‘safety in numbers,’ with little concern of any trouble arising (times were different!).

Different as in safer or less safe? I know lots of young women that age that have taken road/camping trips, and still do.

Safer, of course… the context was that it was highly unusual for them to travel unchaperoned, although that was rapidly changing during the course of their trips.

I owned 3 model T’s in high school. Cheap and reliable. Now I own 2 and have fun on tours. I have met the Silver Streak up close and admired it. I also am one of the instructors at Gilmore Car Museum teaching how to drive them. Come out and try it. Sign up on line. Great experience.

Thanks for stopping by, Jim! (don’t give the story away, though – Parts II and III are coming!).

John forwarded the link to your interview which I’ll add here for anyone interested:

https://www.usatoday.com/videos/news/nation/2017/09/28/museum-brings-model-t-driving-masses/106104480/

I mistook the road trip/camping gear setup as a depression era migration story in the works. This pioneering ladies road trip adventure story is a nice surprise, a great read. Heading over to part 2 now.

Late to the party but had fun nevertheless. Thanks for the piece, a great story well told