(Originally published May 21, 2012) This May, we have been revisiting some of the cars to serve as Official Pace Car for the annual Indianapolis 500. We recently looked at how both the IMS and the auto industry set about revitalizing themselves after World War II. Now, lets hang on as both the race and the industry race into the 1950s.

The Ford Motor Company was back for a second time in 1950 with a shiny Mercury convertible, this time driven by Benson Ford. It must suck being a little brother. “Mom, why did Henry get the Lincoln and I only get a Mercury?”

This Merc is a little less flamboyant than the 1949 Olds 88, but then I guess that was true under the skin as well. Surprisingly, this would not be the last flathead engine to pace the race. But the 1950 Mercury was certainly an attractive car.

In 1936 the tradition was established where the race winner would be presented with the Pace Car as part of his prize package. The ’50 Mercury would not have been a bad prize at all. Johnnie Parsons took delivery of the keys following a rain-shortened race. 1950 would start a string of Pace Cars that celebrated a milestone for its maker. This year, the One millionth Mercury was built.

1951’s choice for the Pace Car marked the introduction of the mighty Chrysler Firepower V8 engine. Chrysler Division President David Wallace got the honor of unleashing the hemi beast at the track, although Chrysler’s Fluid Drive transmissions certainly took some of the fun out of the experience. But having actress Loretta Young as a celebrity passenger probably at least partially made up for it.

The big New Yorker, initially rated at 180 horsepower with a 2 barrel carb, certainly set a new standard for powerful Pace Cars. It was also a powerful symbol that Chrysler was shaking off its 1940s funk and putting its unmatched engineering prowess to work. The 1950s would be a big decade for Chrysler engineering.

Pace Cars as a promotional device had not yet come into their own, as it is reported that not a single replica of the ivory-colored New Yorker Pace Car was built by Chrysler. This probably explains the lack of any easily obtainable color photos of the car. This photo appears to be a different car altogether.

1952 marked another kind of milestone. This was the year that Studebaker Corporation celebrated its 100th anniversary as a maker of wheeled vehicles. Studebaker was, by far, the oldest vehicle manufacturer in the world at that time, and was at the peak of its power and influence in the industry.

Studebaker was the biggest of the independents. Even though it came to the race with a basic car in its sixth year of production, it was still selling a bit under 200,000 of them a year. It also brought a nearly new OHV V8 (introduced the same year as Chrysler’s), a proprietary automatic transmission, and a new 2 door hardtop model. Studebaker was a force to be reckoned with in 1952. Which makes these pictures sort of sad, because as we all know, it was pretty much all downhill from here.

This is also the first year that numerous color photos of the Pace Car are easily found. I particularly like this one. Judging from the output of their respective publicity departments, one would expect that Detroit and South Bend were more than 216 miles apart. More like a million.

Still, the Maui Blue Commander V8 Convertible driven by Stude Executive Vice President P. O. Peterson was nothing to be ashamed of. It’s home-grown OHV V8 made Studebaker part of a still-exclusive club in 1952.

The final flathead paced the race under the hood of a 1953 Ford. Henry Ford’s company was a mere whippersnapper, having been in business only fifty years, but still, it was deemed an event to celebrate. William Clay Ford drove this car. He was the youngest of the brothers, so no Lincoln or Mercury for him. At least he got to drive one, an honor that would not fall to sister Josephine.

This was only the second time that a Ford served as Pace Car, the first being 1935. How do you suppose that the new Chevrolet was so prominently placed in the background of this picture?

The Ford Motor Company ramped up the promotional machinery to an unprecedented degree this year by building about 2,000 Pace Car replicas. These were offered to Ford Dealers and were popular promotional tools to rub in the nose of the Chevy dealer down the block. There are still quite a few of the ’53 replicas out in circulation. But with all of the promotional push, why no color pictures?

Bill Vukovich won the actual Pace Car that year, which eventually ended up in the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, where it can be seen today.

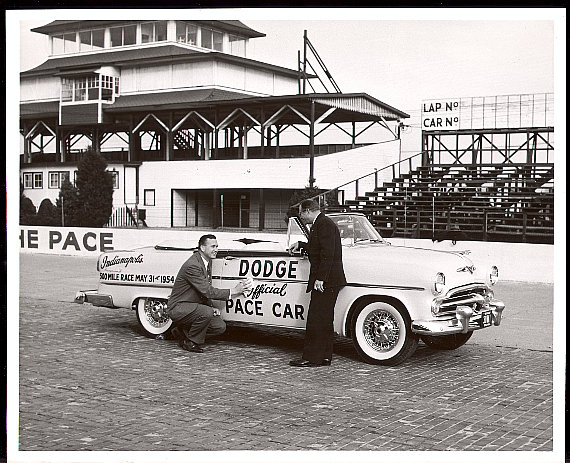

1954 brought Ma Mopar back to Indianapolis with the Dodge Royal 500, a special model atop the Royal line. The car featured Kelsey Hayes chrome wire wheels, a continental kit and a 150 horsepower version of the Dodge 241 c.i. Red Ram V8. It is reported that with some dealer options, the buyer of a replica could get the Red Ram’s output up to about 200.

Only a bit more than 700 Pace Car replicas were made, so while there are certainly some of these around, they are nowhere near as common as the ’53 Fords. Maybe thinking that a little star power could help, Roy Rogers got to pose behind the wheel. Was he the original Dodge Boy?

Does anyone recognize the (probably) famous person waving at us from this photo? Although it is tempting to think that Dodge’s reason for pacing the race was to scream “Look at Me! I’m Not Dead Yet!”, this would not be (completely) true. 1954 marked Dodge’s 40th anniversary.

Chrysler VP William Newburgh drove the yellow Dodge that year. Newburgh would later become noteworthy for being forced out as President after a series of boneheaded moves including profiting from supplier kickbacks. As had been the case for several years, Speedway President Wilbur Shaw rode beside the driver.

Sadly, this would be Shaw’s last appearance due to his death in a plane crash later that year. Shaw was one of the great racers, having first appeared in 1927, and having won the race in 1937, 1939 and 1940. Shaw was the first back to back winner, and was only the second driver to win three times. He was also the last native Hoosier to win the race.

Wilbur Shaw may be as responsible as anyone for the Indianapolis 500 making it out of World War II. Shaw had been conducting tire tests at the Speedway for Firestone, and at their conclusion, Eddie Rickenbacker informed Shaw that the track would likely be bulldozed and turned into subdivisions unless someone could be found to buy it. It was Shaw who convinced Tony Hulman (whose family made its fortune on Clabber Girl Baking Powder) to buy the track from Rickenbacker for $750,000.

Hulman immediately hired Shaw to run the facility, and it was he who was responsible for for its rejuvenation and operation until his death.

Next time, we will look into another new era at the Speedway – one without Wilbur Shaw, but one that would also enjoy a whole new level of game from the U. S. auto industry providing the Pace Cars.

I finally got it – Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis are the stars in the 54 Dodge. I am not sure how I missed it the first time. They must have made friends at Chrysler, because I think that they assembled most of the 57 models themselves. 🙂

Ah yes, Martin and Lewis. For those of you young whippersnappers, Jerry Lewis actually had a career as a comedian before he became synonymous with telethons. And he was ahead of his time – being funny by acting like a complete jerk. Just like what passes for comedy nowadays.

Right you are. Martin and Lewis was a hugely successful comedy team in the early 1950s. Jerry Lewis was a complete bumbling idiot and Dean Martin was the straight man who also sang. They were all over TV and movies in the early 50s. It was not long after this that the team broke up, I forget which one wanted to go solo. Actually, the only times I ever found Lewis particularly funny was in his work with Martin.

One of their final movies together was Hollywood or Bust, and they travel to Hollywood in a gorgeous 1956 Chrysler convertible (can’t remember whether it was a Windsor or a New Yorker).

If I recall correctly, Martin wanted to go solo, as he was tired of playing the straight man to Lewis. Interestingly, the feeling at the time was that leaving the act would hurt HIS career.

Lewis went on to be extremely popular in France of all places though he made many comedy films in the US such as Cinderfella. Loved him as a kid, hated him as an adult. Dean Martin was a great singer and car guy. He paid Ferrari big bucks to make a P330 streetable for his teenage son Dino. OTOH my dad bought me a 150cc Lambretta but it was Italian.

New Yorker

Jerry Lewis, by many accounts, was a complete jerk in real life; he treated his first wife badly and cut his children from that marriage out of his will. He routinely insulted fans at his comedy shows also; unlike Don Rickles, he apparently meant what he said.

OTOH, he raised many millions with his MD telethons.

What’s the saying – best not to examine your idols too closely.

“……nowadays….”

Hmmmm, I seem to remember a comedian NOT quite as old as Mr. Lewis starring in a movie titled THE JERK. So not sure I would say that is a new (ish) phenomenon. And while I am by no means a fan of Jerry Lewis, his original “schtick” was to act like an idiot, not so much a jerk….I think Abbott and Costello had the same kind of act.

BTW, looking at that picture of the Dodge, it almost looks like the person next to Jerry Lewis is wearing a Dean Martin MASK.

I guess I qualify as the third geezer today.

I owned three of these. All 1953 Fords. I almost owned a fourth. A 1950 Olds that was virtually identical to the 1949. I thought of them all as pretty good cars.

What a great way to start Monday morning!

That ’53 Ford special edition came with quite the continental kit; not the usual bumber-dragger accessory. A foreshadowing of Marks to come.

The cute little fender skirts are an interesting touch too. I don’t remember that they were ever common.

I Like the 53 Ford best .

55 chevy has 2 b next

Looking forward to the next installation – I expect there will more variety than the ubiquitous V8 convertible sedan. I know you mentioned the difficulty of covering the earlier cars, but a quick summary of what can be shown would be great. I had a look at the list of pace cars and there are a few names I’m not familiar with.

Really enjoying these Jim. There was a book published in about 1997 on Indy 500 pace cars with a lot of pictures. I got mine in the bargain book aisle at Borders or Brentano’s several years ago.

If you look in Google Books you can read many road test/reviews by Wilbur Shaw in the Popular Science issues of the late 40’s and early 50’s.

Why is Studebaker considered an “independent”? Independent of what?

There were 3 large companies: GM, Ford, Chrysler.

Several smaller corporations were also in the game: Studebaker, Nash, Hudson, Packard, Frazer, Crosley. Willys, Kaiser, Tucker, Muntz, surely others.

“Independent” suggests that the Big 3 were “dependent” recipients of certain governmental entitlements or tax breaks. Was that the case?

If so, then it’s no surprise that that they out-competed the smaller companies.

If not, then what does “independent” mean in reference to the smaller auto manufacturers?

I was not aware that “independent” was controversial terminology. The big companies were umbrella organizations made up of multiple brands and multiple dealer networks. Those had been originally built up by mergers and purchases of standalone companies (like Oldsmobile, Dodge Brothers or Lincoln).

The independent companies were those that stood alone with a single brand to sell. I have understood this to be common usage going back 50 or 60 years, if not longer.

Yes, exactly.

Thanks again. I love the history. As I remarked in another treatise on these pace cars, I have ridden in two rpelicas, one of which was the ’53 Ford.

When I saw your comment yesterday, I thought I remembered that the 53 Ford was really the first time a manufacturer turned the pace car into a huge public relations/special edition thing.

Being here in Indianapolis, pace car replicas tend to be collected, or at least preserved. I have shots of a few (like the 84 Fiero I saw in a gas station one day) and am always on the lookout for more so that I can write up a few of them.

I didn’t realize that in the early 50s Studebaker was 50 years older than Ford…but then Ford never built covered wagons.

Of the cars in this write-up, I’m going to go against popular opinion and say I would like to own the Mercury. The Mercury looks like a metal dumpling, while the 1 year newer Chrysler looks like a tarted up metal box, like a 50s refrigerator.

I’m a Ford/Mercury fan, but I’m not all that crazy about any of Ford’s 42-54 models. Put all the “gingerbread” applied to the 53 Pace Car on to a 53 Mercury and I’d love it. On the Ford? It just looks like an over-decorated, store bought, sheet cake.

Studebaker was the only manufacturer of wagons and carriages to successfully transition to manufacturing cars and trucks. Studebaker was in business before Henry Ford was even born. Studebaker when the got out of the auto business probably should have gone into the beer brewing business like another auto manufacturer had successfully done over 30 years earlier.:)

Interesting analogies. The Chrysler may have been a year newer, but it was about as old a basic design. I didn’t use to appreciate the ’49 Fords that much, but it was a really revolutionary design, setting the format of sedans up to today, and with very nice detail design including in the interior. The only thing that makes them look old is the two flat pane windshield, which was probably a cost thing or not being sure about the mass production of curved glass. GM cars had curved class windshields although still split. Ford knew how to do it, and in fact had a one piece curved windshield in the Lincoln Cosmopolitan from the same time.

The Ford, Mercury, and Lincoln Cosmos were all fresh modern designs, conceived as a whole and not dependent on a lot of trim gimmicks. The Fords have a rounded shape in plan view, tapering front and rear while the GM and Chrysler cars are straight. GM and Chryslers had stuck on rear fenders, but all the Fords had no hint of that.

The postwar Chryslers were the most traditional in concept and construction of the big three cars, and I guess they loaded the heavy chrome on the last year to divert attention from that.

The CC effect strikes again! I was at a car show today and saw a 1965 Pace Car replica.

I won’t name the make and model as I don’t want to steal any thunder from this excellent and enjoyable series.

Question – did the actual pace cars run a stock exhaust system? I can only imagine the sound if these early V8s paced around the track with straight pipes – would be a great way to call the public’s attention to that V8 power.

Correction: Bill Vulkovich won a sales replica 1953 Pace Car that was not used at the race.

Ford Motor Company kept three original 1953 Pace Cars that were used at the race.

No. 3 was given to The Henry Ford museum.

Oh the things that I learn on this site. Who would have ever guessed that there was a connection between Clabber Girl Baking Powder and the Indy 500! I’ll never look at biscuits and gravy without thinking about that little gem.

Looks like Clark Gable seated next to Shaw and the trophy.

Great to re-read this….I see there’s a color photo of the 1953 Ford (though not trackside) here: https://www.thehenryford.org/collections-and-research/digital-collections/artifact/230791#slide=gs-203266