(first posted 8/26/2016) The early days of any new technology are always the most diverse and interesting, as so many different approaches are tried to achieve the same goal. This was particularly the case with automatic transmissions; there were a dizzying array of different engineering solutions to rid Americans of the task of shifting their balky transmissions. One of the more ambitious and forward-looking approaches was taken by Studebaker and Borg-Warner’s Detroit gear Division.

Borg-Warner was by far the largest transmission supplier in the industry, so it was only natural that they also began developing automatic transmission designs. BW had taken an important step in that direction back in 1934 with the first mass-produced overdrive unit, which allowed some clutch-free shifts and “automatic” shifts in and out of overdrive (full story here).

Studebaker and BW’s Detroit Gear Division (“DG”) collaborated on a fully-automatic transmission for some time. Presumably, BW did the heavy lifting, as their experience was much deeper than Studebaker, which bought all of their manual transmissions from BW. But undoubtedly, Studebaker had certain qualities that they wanted to see in the new automatic, the most important one being more efficient and economical than the typical one-speed torque converter units recently deployed by Buick (Dynaflow) and Chevrolet (Powerglide).

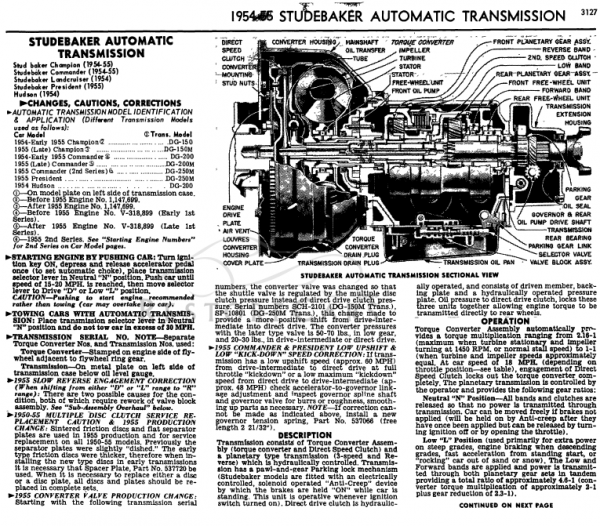

Introduced mid-year in the 1950 model year as an expensive $201 option ($2000 adjusted), the key difference was that the BW DG Automatic Drive (“DG”) had a clutch to lock up the torque converter, essentially turning the unit into a mechanical direct-drive in high gear. The unit had three bands and two planetary gear sets, yielding two forward gears in the conventional sense, inasmuch as high (third gear) was completely direct.

The DG would start in intermediate gear (2nd), which had a 1.4:1 gear ratio. Combined with the torque converter’s 2.0:1 effective gear ratio, starting gear multiplication was 3.08:1. That compares to 2.1:1 for the early Powerglide, which started in direct gear, and thus the DG gave relatively better acceleration. Depending on throttle position, the upshift into direct drive occurred between 18 and 58 mph.

Here’s a more detailed description from a 1950 Popular Science article:

One criticism often voiced against automatic transmissions is that they

deprive the driver of choice. That this isn’t true of the Studebaker/Borg-

Warner drive is shown by the following description of what happens when the

selector lever is in the drive position. It’s also eloquent proof that

motorists must understand their transmissions to get the most out of them.At the moment of starting, with the selector lever at “D,” the power

train is through the torque converter and intermediate gear. Starting

torque ratio in the transmission (not counting the advantage of rear-axle

ratio) is 3.08 to 1, or more than three turns of the engine crankshaft for

every turn of the propeller shaft. Automatic shifts from intermediate gear

to direct drive occur within the following limits, depending on speed,

throttle position and load:1. Starting with a very light accelerator depression, the transmission

shifts from intermediate to direct at about 18 mph.

2. Starting with full throttle (not depressed past the kick-down abutment

on the floor-board), the transmission shifts into direct at about 35

mph.3. Staring with any accelerator depression between between light and full

throttle, the transmission shifts into direct between 18 and 35 mph, depending

on accelerator position.4. Starting with full throttle and accelerator depressed past the kick-

down point, the shift into direct drive occurs at about 58 mph.5. Coasting in direct with accelerator released, the transmission downshifts

into intermediate gear plus converter at 12 mph.6. Direct drive may be over-ruled to provide added torque available in

intermediate by depressing the throttle to the kick-down point at any

speed below 50 mph.”

One wonders whether these cars felt rather sluggish, when shifting into locked mechanical direct drive as low as 18 mph? It’s the same as shifting into third in a manual at that speed. And apparently, the shift from intermediate (with torque converter) into Direct Drive was never a very subtle transition, and could become a bit abrupt if the transmission was not working ideally.

Low gear could be employed manually for climbing or descending steep hills, or for a quicker getaway from start, with a manual upshift required to Drive. Generally, that was not encouraged to be done regularly on these early automatic transmissions as the bands were not designed for repeated use this way. And the shift was never smooth.

The high mechanical efficiency and resulting fuel economy of direct drive was of particular appeal to Studebaker, as it prided itself on its smaller, lighter and more efficient cars. Tests yielded over 20 mpg, depending on engine and driving style. In a 1951 Commander with the new 120 hp OHV V8, tested by three magazines, the average 0-60 time was 17.0 seconds, about 4-5 seconds more than with a manual transmission. 1/4 mile times averaged at 20.8 seconds, top speed 95.9 mph, and fuel economy 22.3 mpg, a very good number considering the times, and for a V8 powered sedan.

Another feature of the Automatic Drive was the Anti-Creep Hill Holder, a solenoid-operated valve that kept brake pressure in the rear brakes after a stop until the gas pedal was depressed. It’s a bit hard to see the benefits in an automatic unlike in a manual transmission.

It should be pointed out that the DG automatic was not the only one with a locking torque converter to effect direct drive. Packard’s Ultramatic also employed a clutch, but only had one normally-used “gear”, like the Buick Dynaflow and early Powerglide. Later units did start in Low, as well as other refinements.

Ford, which was woefully behind in automatic transmission development, asked to purchase and/or also build the DG automatic, which had the potential to lower unit costs for Studebaker. But Studebaker President harold Vance insisted on at least a one-year exclusivity, so Ford went to Borg Warner Warner Gear Division (not their Detroit Gear Division) and bought what became the Ford-O-Matic, production volume to be 50% by Ford, 50% by BW.

This was a somewhat more conventional automatic, with a torque converter and a Ravigneaux planetary gearset allowing three forward gears, although Low was not automatically engaged when starting off. The Fordomatic was the first torque converter automatic to shift without an interruption of its power flow though its torque converter. As such, it was the beginning of two long lines of transmissions: the Ford MX/FX/MFX (Cruise-O-Matic), which was basically a Fordomatic that started in Low (along with other improvements), and BW’s own line of automatics, including the Model 35 transmission, used extensively by AMC and numerous European and Japanese automakers.

Not surprisingly, there were a number of similarities between the DG and the Fordomatic, but the Fordomatic was clearly more pragmatic and cheaper to build.

In 1953, Chevrolet’s Powerglide was reworked considerably, and now started in Low, automatically, which yielded an effective gear ratio of 3.82:1, substantially better than the DG 3.08:1.

So for 1954, several versions of the DG (DG150/150M, DG200M &DG250M) also started in Low automatically. By late 1955, all the versions did.

So for 1954, several versions of the DG (DG150/150M, DG200M &DG250M) also started in Low automatically. By late 1955, all the versions did.

This effectively turned the DG into a three-speed automatic, the first with a torque converter (GM’s four-speed Hydramatic used a fluid coupling), and with a locking one at that.

For two brief years (1954-1955), Studebaker’s automatic was the most advanced and most efficient in the land. But it ended all-too soon.

Studebaker sales swooned in 1955. BW demanded a substantial price hike for their complex DG transmission, due to the low volumes. Studebaker decided to buy BW’s other automatic, essentially the Fordomatic, now dubbed Flight-O-Matic.

Curiously, some of the Flight-O-Matics started in Low, others not. The initial 1956 version used on the V8 Commander did, but that was changed mid-year. Apparently the shift from Low to 2nd was not smooth enough, and Low gear was noisy. And typically, these transmissions shifted from Low to 2nd very soon, like around 7-8 mph, thus not fully utilizing the engine’s power band.

By 1957, there were two versions of the Flight-O-Matic; the V8 version started in 2nd, but the lighter six cylinder version started in Low. The issue of modifying these transmissions to give a start in Low, or hold low until 25-30 mph, is one of on-going interest to Studebaker enthusiasts, as this forum page attests.

The DG didn’t end with Studebaker in 1955. Tooling was sent to England, were it was built and used in Jaguars for a number of years. There was even a modification, an upshift retarder, to keep it from shifting into Direct Drive too soon, which rather spoiled the already-dulled performance of the XK engine further.

It was also used by other European makes, including Mercedes, for their 300 sedan. I had always wondered what they used in that, as they did not have an automatic of their own at the time. Given the Mercedes-Studebaker connection (Studebaker-Packard was the US Mercedes distributor), that makes a rather fitting solution. The transmission Studebaker could no longer afford ends up in their luxury import. And makes servicing it at Studebaker dealers readily possible. What goes around, comes around. Or gets locked up, in the case of the DG’s torque converter.

More on vintage transmissions:

Powerglide: A GM’s Greatest Hit or Deadly Sin?

Planetary Overdrive (Borg Warner)

Lincoln’s Liquamatic Drive: Failure To Upshift

Interesting reading , THANK YOU .

I have a four speed slushbox in my various old Mercedes Diesels and they all shift out if first _way_ too soon .

I’m actually a fan of the old B-W 35 series slushbox , it’s simple and durable although could use a lockup torque converter for to – day’s highway speeds .

-Nate

Does the M-B four speed auto have a torque converter, or just use the various gear sets for torque multiplication? I ask because the old GM four speed Hydramatics did not have a torque converter, using only the gears. First gear had a really low ratio and the transmission typically shifted into second at around 5 MPH in normal operation. Even a full throttle start would result in the 1-2 shift happening at no more than 10 MPH. Even the B&M Hydrostick, which was an option to allow manual shifting of these transmissions and was reasonably popular with drag racers, made no provision for manually shifting between first and second. Instead the 1-2 shift was automatic and then the 2-3 & 3-4 shifts could be accomplished at the driver’s discretion.

Yes ;

It has a torque converter .

Like you said , it up shifts before the car goes 20′ .

I’ve had many Hydromatic Drive vehicles and they all were very nice , the fluid couple worked just like a torque converter does in use .

I don’t know anything about how the Hydromatic’s coupling actually works bit there’s _something_ that gives on one side an not on ther other…

.

-Nate

The early four-speed Mercedes automatic did NOT have a torque converter; it had fluid coupling. The three-speed unit adopted in the early ’70s had a torque converter. Like Hydra-Matic, the four-speed had a very, very low (high numerical) first gear, so even if you held it manually, its top speed was in the 25–30 mph range.

I wrote at great length about early and later Hydra-Matics not that long ago, but suffice to say: a torque converter is a type of fluid coupling. However, a torque converter has additional elements that allow it to multiply torque under certain conditions, which a two-element fluid coupling like the ones used in Hydra-Matic and the early Mercedes transmission does not.

Thanx ;

I was talking about the four speed (?722?) automatics in my W123s here .

-Nate

Ahh — the much later four-speed unit was indeed a torque converter transmission. From the context, I assumed you guys meant the Mercedes automatic introduced in 1961, which was quite a bit different.

“Ahh — the much later four-speed unit was indeed a torque converter transmission. From the context, I assumed you guys meant the Mercedes automatic introduced in 1961, which was quite a bit different.”.

Thanx ! .

It’s nice to have someone who understands these details ~ I saw a Hydromatic all apart on the bench in 196? and thought ” that’s that ~ I’ll never be able to overhaul slushboxes, too complicated” .

-Nate

Your last comment about how the Hydramatic’s coupling works is not clear to me; how a fluid coupling works vs torque converter, or how the hydramatic was constructed?

The engine was connected to the first planetary gears, with a 1.5:1 gear ratio (roughly). The fluid coupling is next, so the impeller runs at 2/3 the speed of the engine at idle. The second set of planetary gears are connected to the fluid coupling’s turbine, and have a 2.5:1 gear ratio (roughly). The third set of gears are for reverse. First gear is both gear sets shifted down for a 3.8:1 gear ratio. The first set upshifts first for second gear (2.5:1), then to get to third both gear sets have to shift together. I don’t know how the torque split works in third and fourth gears though.

The basic difference between a fluid coupling and a torque converter is that there is a stator in the torque converter. In both the impeller pumps the transmission fluid around or into the turbine. The turbine is designed to convert the momentum that the oil has into torque on the driveshaft which will cause it to turn. Since the fluid coupling has only two elements (an impeller and a turbine) the oil exits the turbine going opposite to the impeller direction. With a torque converter, the stator’s function is to redirect the oil in the direction of the impeller so it has less work to do. This results in an amplification of the engines torque.

Head on over to AteUpWithMotor; he’s got the full scoop on the Hydramatic and other early GM automatics: http://ateupwithmotor.com/terms-technology-definitions/hydramatic-history-part-1/

I did look at that (page 3 relative to your link) before commenting. Now that I have studied it more I see what I did not understand before. The second planetary gear is not locked up in third and fourth gear, as I had assumed, but the different elements can turn at different rates, which splits the torque flow from the engine.

There is no reason why a torque converter could not replace the fluid coupling.

There’s not any reason they couldn’t have used a torque converter instead of a fluid coupling, but GM’s transmission engineers really saw torque converters and coupling/geared automatics as separate development paths: one offering maximum smoothness with no steps, the other offering maximum efficiency. Until the early ’60s, the closest they came to combining the two was the 1953 and later Powerglide, which I’m pretty sure was instigated by Chevrolet divisional engineers rather than the corporate staff that developed most of the underlying technology. It’s not that they didn’t know how to combine a torque converter with stepped gears, but that they were trying very hard to avoid doing that.

Of course, Hydra-Matic with a torque converter would have needed different internal ratios, but that’s sort of a secondary point.

“I’m actually a fan of the old B-W 35 series slushbox , it’s simple and durable although could use a lockup torque converter for to – day’s highway speeds .”

As far as I know the last automotive use of this transmission was a front-drive variant used in the first-gen Saab 900. (Through 1993 for sedans & hatchbacks, 1994 for the Saab 900 convertible.)

im helping my younger brother, 79, with his 66 studebaker commander with the 283cu engine. first the trans needs rebuilt, we need to find a kit first then some shop in san antonio the is familiar with it. i want to put powerglyde or 350 trans in it but he tells me too many obstacles. is there a problem mounting the starter etc, i can build the crossmember and have a driveshaft co for that, just need to know what to do to help.

Maybe try Transmatic in ? Glendale ? Ca…….

They had parts for my 1979 JATCO M35 slushbox right on the shelf at reasonable co$t .

-Nate

Somewhere in my reading about the independents in the 50s, I came across a paragraph that said that B-W approached Nance, sometime in 55 or early 56, with an offer to buy all the Packard Ultramatic production tooling, if Packard would switch to the B-W transmission. Can’t help but wonder of the DG-250 could take the Packard’s torque better than the Ultramatic could.

It would have been interesting to see if the Independents could have lowered their unit costs and improved quality control if they had consolidated some things like transmission production and development.

if they had consolidated some things like transmission production and development.

iirc, Packard was the only one to develop an automatic on it’s own. The Detroit Gear transmissions had been partly funded by Studebaker, which gave Studebaker a veto when Ford wanted to use the DG.

There were such titanic egos in those smaller companies that it was very difficult for them to work together. Nash agreed to buy Packard V8 engines, because they were desperate for a V8 and Packard was the only V8 producer desperate for the business. Then Packard demanded Nash buy the Ultramatic with the V8, because they were exploiting Nash’s desperation.

Packard was supposed to buy parts from Nash too, but every time Packard sent an RFQ to Nash for a part, the quote came back at double or triple the price Packard could get the same part for from other vendors.

AMC approached S-P about buying the Studebaker V8 for the Statesman, but S-P brushed them off. S-P approached AMC about buying the OHV 196 to replace the old flathead Champion six. Romney blew off S-P. Both of these companies were on the brink of bankruptcy at the time and could have used the extra business, but nope, ego got in the way.

And in the comment immediately following this one, it’s stated that no less than Ford used a GM transmission in their ’49-’54 Lincoln. GM was more than happy to sell transmissions to Ford if it meant money. It helps explain how the independents, with their petty egos and bickering, got in the way of sorely needed profits while, conversely, the much wiser big guys simply did whatever they needed to make money. It’s no wonder that all the independents eventually folded.

Sad, sad, sad, when egos triumph over common sense.

To be fair, the point GM’s Detroit Transmission Division started selling Hydra-Matic outside the company was after Packard had already designed Ultramatic. Before that, I think Detroit Transmission was straining just to keep up with internal demand, particularly after Hydra-Matic became optional for Pontiacs in 1948. It wasn’t until the Livonia plant was constructed that non-GM sales started.

It probably helped GM’s decision-making that Cadillac utterly dominated the luxury segment and GM was afraid of getting trustbusted.

I recall reading somewhere that Hudson used the Studebaker DG as a temporary replacement after the Hydramatic plant burned. Hudson aficionados are not DG fans as the transmissions were overtaxed by the Hornet’s torque.

Hudson aficionados are not DG fans as the transmissions were overtaxed by the Hornet’s torque.

The Hudson manual trans couldn’t take the 308’s torque either. There are plenty of commentaries around about the 308 twisting the trans input shaft. When AMC put the 308 into the Hash, they made several improvements, one being using the standard Nash B-W manual trans, which was a lot stronger than the Hudson trans. There is a thread on HAMB with pix comparing the Hudson and B-W input shafts.

If Hudson had trouble with the DG, I really wonder about the report I read of B-W trying to get it’s trans into Packards, in place of the Ultramatic, considering the trouble the 55 Ultramatic gave with the V8. Even the downrated 320 sold to Nash caused so many problems with the Ultramatic that a Nash training film for 56 admits to salesman that the Packard sourced powertrain had been problematic in 55, but promised all the issues had been solved.

“Ford, which was woefully behind in automatic transmission development”

That is no joke. From ’49 – ’54 Ford had to swallow its pride and install GM Hydra-Matic transmissions in their Lincolns.

Nothing says buy a Lincoln over a Cadillac quite like admitting that the Lincoln has a GM transmission!

Hydra-Matic was quite aggressive about marketing it’s transmissions outside of GM. Beside Lincoln, Kaiser, Hudson and Nash all used Hydra-Matics in the mid 50s. iirc, AMC switched to Borg-Warner around 58. My reading has not turned up the reason for the switch, whether cost, or if GM decided to keep Hydra-Matic transmissions for itself.

Trivia bit: the Hydra-Matic plant in Livonia, MI, burned to the ground in the summer of 53, GM divisions had to switch to Dynaflow or Powerglide transmissions, and the outside customers did without. When Hydra-Matic production resumed, the first transmissions shipped were to the outside customers, as a goodwill gesture, according to management. In the back of my mind is the thought that the first transmissions might have been a bit questionable due to the hastily set up production line and disrupted workforce, so they were handed off to outside customers while GM divisions waited for the line to be run in for a bit before taking new production.

“…the Hydra-Matic plant in Livonia, MI, burned to the ground in the summer of 53, GM divisions had to switch to Dynaflow or Powerglide transmissions, and the outside customers did without. When Hydra-Matic production resumed…..”

Steve, Don’t forget to mention the plant sourced in a hurry to resume Hydra-Matic production was the massive Willow Run – Kaiser/Frazer behemoth, now greatly under-utilized as Kaiser and Henry J sales sagged badly. Edgar Kaiser, by then running the show after Joe Frazer bowed out of that sinking ship, must have been mightily relieved to unload that albatross. Wags said Edgar lit the match……..

Don’t forget to mention the plant sourced in a hurry

Kaiser bought transmissions from Hydra-Matic, so Edgar already had contacts there.

The timing could not have been better as June 53 saw the cancellation of all Kaiser’s Air Force contracts, which were profitable, cancellation of the contract to provide Henry Js to Sears and the UAW going on strike. The irony of the collapse of Kaiser that summer is that, in the spring with the plant churning out C-119s along with a trickle of cars, employment at Willow Run was at it’s peak. Some shareholders were demanding Kaiser exit the car business and do nothing but defense contracts.

I am reasonably sure AMC’s switch to BorgWarner was for cost reasons. They did briefly use the second-generation Hydra-Matic, but it was a lot more complicated and a lot more costly than the earlier single-coupling units.

Size and weight were probably also issues once they went to an all-Rambler lineup.

Well, the single-coupling Hydra-Matic was available even on the original 100-inch-WB Rambler and the dual-coupling version was available on 1957 108-inch-WB Ramblers, so it wasn’t that it didn’t fit. Most of the early iron case automatics were quite heavy, so I don’t think there was a big advantage in that respect. I think it probably came down to cost.

Studebaker Automatic Drive is the simplest-the safest-the thriftiest of all!

That ad basically screams ” So Simple, Even A Woman Can Do It!” Wow!

Which was pretty typical of the era. Everything from power steering to getting rid of the starter crank was aimed at “look, now your wife can drive!”

After World War Two the chauffeur driven cars are fading fast, Cadillac’s Fleetwood 75 lineup for example. Probably during the War many women figured out that they could do a lot (or their husbands were gone) like driving.

The classic movie “The Big Sleep” has female♀ taxi drivers, as filming was done during the War & it was another excuse to get a pretty face on camera. Of course they were ●more● than happy to drive Philip Marlowe around!

There was also the precedent set by the WASP program (women pilots), even though most bombers then had unboosted controls (e.g., one could tell a B-24 jockey by his muscular left arm).

The B-17 was easier to fly according to pilot reports. The B-24 was basically gone from USAAF service after the war ended.

The hydramatic did not lock up the fluid coupling as I understand it, but somehow in third and fourth gears the engines torque bypassed the fluid coupling on the order of 50% in high gear, less in third. Ate up With Motor has an explanation.

I’ve actually been planning to do a little followup piece on that specific point: split torque transmissions, which GM used for a variety of its early automatics. I talked about the layout in the existing articles, but how it works is a little more involved.

As a late addendum, it’s useful to note, vis-à-vis the DG transmission’s mechanical top-gear lockup, that conventional wisdom in automotive engineering in the fifties and sixties didn’t consider hydraulic slip in a fluid coupling or torque converter to necessarily be a bad thing, despite the fuel economy penalties.

There were two main considerations: NVH (noise, vibration, and harshness) and torque performance. From an NVH standpoint, having a hydraulic rather than mechanical connection between the engine and the drivetrain served to damp out some vibration, including both road shock and engine vibration. From a performance standpoint, it was sometimes beneficial to allow engine speed increase relative to road speed in a given mechanically geared ratio, for extra torque.

The reasoning for the latter will make more sense if you’ve ever driven an underpowered manual transmission car in the mountains. In those conditions, you run into some frustrating moments where top gear isn’t giving you enough torque to maintain the speed limit, but you’re really going too fast to downshift, so you have to just settle for whatever speed the engine can pull in high. With a fluid coupling or torque converter, the engine can rev higher in conditions like these, which may produce more usable power and torque for a given road speed; the torque converter may also give you some additional torque multiplication. (This was one of the saving graces of the old two-speed Powerglide — although you generally couldn’t kick down above about 45 mph, the transmission would pull generally harder in high than a three-speed manual in top gear because of the converter.) Doing that generates more heat in the coupling or converter, and it burns more fuel, but even with a manual transmission, a long grade is going to have the engine working pretty hard (and may have the temperature gauge rising ominously), so those factors aren’t necessarily deal-breakers.

One of the downsides of the DG gearbox in this respect is that in top gear, you had no torque multiplication at all: Once it shifted to third, there was no mechanical reduction, no possibility of converter reduction, and no slip to allow engine revs to rise. While that was beneficial for fuel economy in straightaway cruising, it meant the transmission was no help at all in hilly terrain unless you were able to kick down to and hold second. In fact, it was undoubtedly a little worse than a manual three-speed under load in top gear because you still had the parasitic losses caused by the two transmission oil pumps.

(When the lockup torque converter clutch made a comeback in the late ’70s, it was typically set up so that the lockup clutch would engage after shifting into top gear — and sometimes when running in the intermediate gear(s) as well. Driving an underpowered car of the early to mid-80s with a three-speed automatic, you’d tend to get a lot of clunking as the converter clutch locked and unlocked in top gear, with the occasional double-clunk of converter unlock/kickdown. The DG couldn’t run in top gear with the converter unlocked because the direct drive clutch basically locked the flywheel to the output shaft; unlike later lockup arrangements, or Packard Ultradrive, the converter was always idle in direct drive.)

This is a very relevant late addition; thank you. It’s a key point all too-often overlooked, as there seems to be too much focus on the perceived benefits of a direct drive top gear as in the DG. People tend to forget that what really attracted buyers to the early automatics was the promise of a very smooth (“slushy”) drive train, as a counterpoint to the non-syncro first gear manual three-speeds that were just not very pleasant to drive for those that didn’t have the right mindset/orientation.

You mention the benefit of some slip in high gear to increase engine power from a fluid coupling. Did that really happen with them? What was their effective stall speed? I had assumed that would not happen at anything but very low engine speeds.

The Powerglide is one of those automotive icons that is all-too often maligned way beyond what it deserves. It’s remarkable efficiency, simplicity and durability combined with its smooth drive deserves greater respect. But of course it hung around a bit too long, and that’s undoubtedly where much of the negative impressions were formed.

@ Paul: With any kind of fluid clutch, any change in load will allow the impeller speed to increase faster than turbine/output speed. In a fluid coupling, this won’t ever multiply input torque because there’s no stator, but because an engine will generally produce a little more power and torque at, e.g., 2,200 rpm than at 1,800 rpm, it can still give a small momentary boost in performance. How much and for how long depends on the actual load conditions.

The effect is obviously more pronounced with a torque converter because in addition to any increase in engine rpm, the change in load and flow conditions will tend to lock the stator(s), which provides torque multiplication. This generally won’t give you the full stall ratio, because the stator blades aren’t at the best angle for for that (this was the rationale for variable-pitch stators), but it’s still helpful because it’s giving you more torque than the engine can produce at a given rpm.

In either case, the relationship between engine speed and transmission speed remains at least somewhat variable regardless of road speed or what gear the transmission is in, because it’s based on load (and the way changes in load affect the flow patterns within the fluid clutch) and time (because the driven torus or torii will eventually “catch up” with the impeller and enter coupling stage).

Although the variable relationship between impeller and turbine rpm continues in all gears, the concept of stall speed really only applies to breakaway (starting from rest). Stall speed is the impeller speed at which the torque applied to the turbine precisely equals its inertial load — essentially, the instant before the turbine begins to rotate. (This is why in real-world terms, stall speed is not fixed and varies based on conditions like the total weight of the car and whether it’s on a grade.) Once the vehicle is moving in gear, the turbine is spinning; what varies at that point is how fast it’s rotating relative to the impeller.

Part of what makes it harder to get a handle on this stuff is that modern powertrains with torque converters are generally designed to keep the converter locked up as much as possible once the vehicle is moving faster than a walking pace. That wasn’t necessarily the case with older transmissions, which was generally by design. (For instance, one of the claims the designers of the original Hydra-Matic made for that transmission’s unusual layout was that it effectively tailored the fluid coupling’s characteristics in each gear to suit different operating conditions.)

Stall speed is the impeller speed at which the torque applied to the turbine precisely equals its inertial load

Oops, this should have said “Stall speed is the impeller speed at which the torque applied to the stationary turbine precisely equals its inertial load.” So, if the impeller is driven directly by the engine and the converter stalls at 2,400 rpm, that means that the engine can rev to 2,400 rpm before the turbine starts to move from rest.

(Again, actual stall speed varies depending on the inertia of the vehicle and the drivetrain, as evidenced by the fact that a vehicle with a fluid clutch will typically “creep” slowly if you take your foot off the brake, even though the engine’s idle speed is less than half of the fluid clutch’s rated stall speed.)

Thanks for the very clear explanation.

@Ate Up With Motor

This graph of a torque converters characteristics may be useful:

https://www.hemmings.com/stories/article/torque-to-me

This is a Chrysler torque converter, but the Powerglide’s is probably similar. One can see that the torque ratio is greatest at a standstill and decreases steadily with the increasing speed of the turbine. The impellers speed increases slowly until the turbine has reached about 80% of the impellers speed. From there the impellers speed increases rapidly as well as the turbines speed. The torque ratio is 1:1.

What the graph shows us is that at 80% (8 on the lower axis (.8)) the impeller is turning at 2000 RPMs and the turbine is turning at 1600. This is about 40 MPH depending on the axle ratio of the car. So above 40 MPH the torque converter is 1:1 for torque ratio. Below 40 MPH the torque ratio will increase.

By 3000 RPMs the turbine and impeller are running at nearly the same speed, but the turbine will always run a bit slower otherwise no power/torque can be transmitted from the impeller to the turbine.

@persona: The important qualifier in that graph is “constant input torque.” With any fluid clutch, efficiency increases and speed difference will drop (and with a torque converter, torque multiplication will decline) in a similar way under constant load.

However, a CHANGE in load will result in a bigger difference between input and output rpm, which with a torque converter can also mean a resumption of torque multiplication. It won’t be as much as at stall, but if the flow conditions allow the stator(s) to lock (rather than freewheel) and redirect oil flow, there will be some. As turbine speed catches up with impeller speed, efficiency will increase and the stator(s) will freewheel again. This will follow the same KIND of pattern shown on that graph, but it’s not on the same fixed torque ratio/rpm schedule as you get when accelerating from rest under constant load; it’s based on load over time.

Taking advantage of this is why GM got into variable-pitch stators, starting with 1955 Dynaflow transmissions. The idea was that the stator blades could change their angle to provide greater multiplication during a temporary increase in load, like passing. (If you’re curious about the principles, see U.S. Patent No. 2,999,400, which describes the dual-position stator used on Buick twin-turbine transmissions, and 3,008,349, which describes the ambitious continuously variable stator used on the Triple Turbine transmission.)

I have the graphs for the twin turbine dynaflow with variable pitch stator. I think once the turbine reaches a high enough speed to fully couple, it will not decouple. However torque converter design vary. The twin turbine dynaflow seems coupled at 2500 RPMs in performance mode, but at 2000 RPMs in normal mode. The stall speeds are 2500 and 1500 more or less. In performance mode the torque ratio is greater.

@persona: Stall speed is not relevant once the vehicle is moving, because the turbine is rotating, and thus is not stalled.

With any fluid clutch, there is not a fixed relationship of input to output rpm because the driving torus and driven torus are not physically connected like a mechanical gear. Any time the impeller speed increases, there’s a lag before the turbine catches up and resumes coupling stage. If the speed difference is big enough, there may be torque multiplication. It depends on load and how much speed difference there actually is; as that graph indicates, if turbine speed is too close to impeller speed, there won’t be any multiplication (because the oil flow will hit the back of the stator and cause it to freewheel). However, it has nothing directly to do with stall speed, and it’s not necessarily on the same rpm-to-torque-ratio schedule as you see when accelerating from rest.

Also, stall and coupling are not the same thing. Coupling stage is where the flow of the oil within the fluid clutch is mostly circumferential (rotary flow), impeller and turbine speed are very close, and input torque is being transferred with as little frictional loss as the physics permit.

Coupling stage isn’t tied any specific input rpm; it can occur at almost any constant input speed, as long as there’s still enough input torque to overcome the friction and inertia of the rest of the transmission and drivetrain. The important qualifier there is that the input speed needs to be constant (or nearly constant), so there’s minimal disruption of circumferential flow. Significant speed changes will increase toroidal flow and slippage, and the torii will no longer be coupled.

A *VERY* good point ! .

This is why the factory Hot Rods came with “High Stall” torque converters .

Sadly often they’re lost when sent in for tranny rebuilding .

To me, the late 1970’s lock up torque converters GM used was the best option, one could add a cut out switch to prevent the locking up before you want it to .

Power Glides may be hated by some but the circle racers loved them as they were simple, cheap and *very* hard to break when you were putting too much horsepower through them .

Everyone who had a power glide in an early Chevy hated them of course .

-Nate

Powerglide was a pretty viable alternative to a contemporary three-speed manual transmission, which was how it was typically sold in the ’50s and early ’60s, and it was a much better value than a four-speed manual, even a decent all-synchro gearbox, in terms of resale or trade-in value. When all-synchro four-speeds became optional, they cost about as much as Powerglide, but you wouldn’t get that cost back in trade AND you’d take an extra hit at trade-in time for not having automatic.

(I’m referring here specifically to two-speed Powerglide transmissions. The early non-shifting Powerglide was not a workable alternative to anything except walking or maybe riding a bike, and the latter might have been faster unless it was raining or snowing.)

My understanding of what the torque converters stall speed is as follows:

the turbine is held stationary and as power is increased to the impeller, the impellers speed increases up to the stall speed. Once the impeller reaches stall speed, adding more power does not increase the impellers speed.

So the stall speed is fixed or designed in for any torque converter.

I think by “impeller” you mean “turbine.” In any fluid clutch, the impeller is the driving torus (which service manuals sometimes describe as the pump), which in many transmissions (with the notable exception of some older Hydra-Matic transmissions) is driven directly by the engine. The driven torus is called the turbine; some transmissions have more than one, although that’s rare in automotive applications today.

The impeller starts turning when the engine is running. That rotation is transmitted by the oil in the fluid clutch to the turbine. At low speeds, like at idle, most or all of this motion is absorbed by the oil, and not enough torque is applied to the turbine to overcome its inertia and the friction of the various transmission components to which it’s attached. Stall speed is the point where the torque applied to the turbine equals those inertia and frictional loads, beyond which the turbine will start to rotate, transferring its motion to the transmission gear.

Once the turbine is rotating, it will try to catch up with the rotation of the impeller. It won’t ever quite match it, because some energy is always lost to slip, but given enough time, it’ll get pretty close — say, 97% of impeller speed.

A torque converter adds an additional reaction member between the impeller and turbine, called a stator. (Some transmissions have more than one.) When impeller speed is significantly greater than turbine speed, the stator will redirect some of the oil flow for greater efficiency, which multiplies torque. The amount of multiplication is variable because it depends on the speed difference between the impeller and turbine. Once turbine speed gets fairly close to impeller speed, the stator will start to freewheel so that it doesn’t get in the way, and when it’s freewheeling, it can’t multiply torque.

Although it’s often used mostly as a clutch, a torque converter is a continuously variable transmission. Because the impeller and turbine are not mechanically connected, the speed of one can and does always vary relative to the speed of the other. The only way to prevent that is to use a mechanical clutch to force the impeller and turbine to turn at the same speed (which is how most modern lockup converters function) or to bypass the converter and allow the engine to drive the transmission directly (which is what the DG transmission described in this article did).

Also, to understand what I was talking about, it’s important to understand that there’s a difference between the rated stall speed of a torque converter or fluid coupling and the ACTUAL stall speed. The rated stall speed is a nominal maximum value under certain specific conditions. It’s useful for comparisons — a high-stall converter will always tend to stall at higher rpm than a low-stall converter — but it doesn’t mean that the converter will always or only stall at precisely that speed, nor would you usually want it to.

For any given fluid clutch, stall speed will vary depending on input torque, the vehicle’s current weight, the friction and inertia of the transmission and drivetrain, and even the grade on which the vehicle is currently sitting. Think of it like slipping the clutch to start from rest with a manual transmission: If you’re starting on a steep hill with a carload of passengers, you might have to slip the clutch while revving the engine quite a bit to get moving, but with just you on a level road, you might get away with engaging the clutch just above idle speed because there’s a lot less inertia to overcome.

This article supports what I said above:

https://www.motortrend.com/how-to/0808rc-torque-converters/

The only part of that article that differs from what I said above is the author’s attempt to explain the transmission shop guy’s description of stall speed, which is factually incorrect and kind of misleading. (The transmission shop guy’s statement is correct, the author’s summary of it is not.)

It would be reasonable to say that stall speed represents the largest difference between impeller and turbine speed a given fluid clutch will permit. However, the way the author of that article describes it is wrong.

A torque converter, especially in a non-electronic transmission, does not “hold back” engine speed. What holds back engine speed when brake-torquing are the brakes! In the example given, once the engine has reached 2,500 rpm, engine and converter torque are being applied to the transmission gears and driveshaft, which would cause the vehicle to accelerate, except that the brakes are holding it stationary.

While you can’t brake-torque a conventional manual transmission (the engine would just stall), if you try to accelerate and brake simultaneously with the transmission in gear and the clutch engaged, the brakes will resist the engine accelerating; you wouldn’t call that the clutch “holding back” the engine. (I suppose you could, since if you disengaged the clutch, the engine would be free to rev, but it would also be missing the point.)

I’m afraid that I don’t understand.

I’m not sure which part is hard to understand, except that the Motor Trend writer’s description of what stall speed represents is incorrect and misleading. (The rest of the article is a pretty solid description, and the quotes from the transmission shop guy are pretty correct, but the author stumbled on that paragraph.)

Because a torque converter is a type of clutch, it’s tempting to think of it in the same terms as a mechanical plate clutch, where you slip it somewhat when starting, but then it engages fully and is no longer a consideration until you need to stop or change gears. A fluid clutch isn’t like that: engine torque has to be transmitted through the oil, and so there are always speed differences between the impeller and turbine and there’s always some lag and slip, not just when starting, but any time engine speed changes. This is why torque converters are now usually equipped with lockup clutches — a lockup clutch is a separate mechanical clutch that provides the direct one-to-one mechanical connection the torque converter itself cannot.

Stall speed has a specific definition, which I noted earlier: It’s the point where the torque exerted on the stationary turbine exactly equals the load on that turbine, imposed by friction and inertia. When brake-torquing (revving the engine while stepping on the brake pedal), once engine speed reaches that point, engine torque is trying to turn the drive wheels and being held by the wheel brakes, so the engine can’t rev higher unless it has enough torque to overcome the brakes.

Your last paragraph seems to say exactly what I said above.

I love this thread .

I’m not sharp on how the hydraulic coupling works but this made it much easier .

I think the end point it : the stall point is how fast the engine can rev. in gear when full stationary…..

-Nate

(how hates ‘high stall’ torque converters)

You’re not understanding (and the author of that Motor Trend article either didn’t grasp or didn’t do a good job of explaining) what the stall speed represents. It’s not a matter of the torque converter “holding back” the engine beyond a certain speed — what’s doing that, in the case of brake-torquing, is the brakes! — and the converter would have no way to do that in any case. (A torque converter is complex in terms of fluid dynamics, but mechanically, it’s pretty simple.)

Stall speed is NOT a fixed point. (Rated stall speed is just a nominal maximum value under specific conditions, not unlike rated horsepower.) If you aren’t holding the vehicle stationary with the brakes while revving the engine, the stall speed will be whatever point at which input torque matches drivetrain inertia, which in many cases will be a lot less than the converter’s rated stall speed, and which won’t be marked by any restriction or limit of engine revs. Also, if the converter can vary the pitch of the stator blades, it may effectively have several different nominal stall speeds, although how that works in practice will depend on how the stator pitch is controlled.

Fluid clutches can be designed so they stall at lower or higher rpm (“tight” versus “loose”), which will give them different nominal stall speeds, but the actual stall speed of a given fluid clutch will always vary depending on operating conditions, and in practice, a high-stall converter might sometimes stall at lower speeds than a nominally low-stall converter. (For instance, if you make a gentle start on level ground with the high-stall converter, stall will probably be lower than launching the low-stall converter on a steep hill while the vehicle is loaded to the gunwales.)

More importantly, as I was saying originally, once a fluid clutch is beyond stall speed (whatever stall speed happens to be in the circumstances), there is still a nonlinear relationship between impeller speed and turbine speed, and, in a torque converter, there can still be torque multiplication.

If one looks at graphs like the Chrysler one, it’s easy to get the mistaken impression that a coupling or converter is like an automatically controlled manual clutch, where it will hit a particular preset rpm and then lock up and stay locked up thereafter, but that’s not how a fluid clutch works, unless it ALSO has a separately controlled mechanical lockup clutch. It’s helpful to consider the latter separately, because for many years, most automotive transmissions with fluid clutches did NOT have any provision for converter lockup, the DG and Packard Ultramatic being obvious exceptions. Hydra-Matic, Powerglide, PowerFlite, Fordomatic, and Dynaflow didn’t have lockup clutches, and TorqueFlite and Turbo Hydra-Matic didn’t get them until the late ’70s.

Alternatively, you can think of the stall speed like this: In a fluid clutch, impeller speed will always be at least somewhat greater than turbine speed. How much greater will vary, but stall speed represents the maximum possible difference, and coupling stage is the smallest possible difference.

Your right about one thing, I don’t understand what your getting at. I think that I understand what the stall speed is.

The point I was trying to make is simply that in a fluid clutch without a separate mechanical lockup clutch, the relationship between impeller and turbine speed is always going to be flexible — not just when starting, and not only at certain rpm. That’s why mechanical lockup clutches were developed.

What I see in the Hemmings article’s graph divides the torque converters performance into roughly two states. If the vehicle is cruising at a steady speed of 20 to 25 MPH, then the turbine is turning at 800 to 1000 RPM’s, assuming an early 60’s car. This puts the turbines speed around the 5 to 6 mark on the lower axis (which is really .5 to .6). This state is what I would call “slushy” meaning that the impeller can vary its speed over several hundred RPMs. Of course if the impeller speeds up then the turbine will accelerate, unless the car is moving up a steep hill and power is limited to keeping the car at a steady speed.

On the other hand if the car is cruising at 60 MPH, the turbine is turning at 2400 RPMs. The puts the turbines speed at about the 0.95 mark on the lower axis. The impeller and turbine a coupled with the difference in speed on the order of 100 RPMs or so. The torque converter is fairly efficient with some slip. If the car starts climbing a hill and more power is applied to the impeller, it will only increase it speed by about 100 RPMs and the torque ratio will remain at 1:1.

So for a car climbing a steep hill at 20 to 25 MPH, requiring full power to keep the speed constant, the torque ratio would increase to about 1.5:1 more or less.

Probably the transmission would downshift though.

It would depend on throttle opening. WOT would trigger a kickdown, but at part-throttle, it might not. One of the priorities for multispeed transmissions was to limit “hunting” between gears, so the control system might allow a fair degree of throttle opening before downshifting, relying on the converter to bridge the gap.

It’s interesting to note that the 1954 Hudson is listed in the manual pages you printed in the story. Was Hudson an exception to the 2 year rule due to the Hydra Matic factory fire?

I had a 61 Austin Westminster 6/110 that was equipped with a BW/DG auto it had an overdrive feature on the lower two gears and could be wound out to 70+ mph in second gear, it could also be tow started dropping it into drive at 20+ mph would turn the engine, pushing with another car is recommended in the owners manual, the car also came with a crank handle unfortunately reverse band failed which limited the cars usefullness and it ended its day in a demolition derby.

Minor correction: the stall ratio of early Powerglide units was 2.20:1, not 2.10. The latter stall ratio was adopted for 1953 and later units. Aside from a different control system, ’53 Powerglide units got a completely different torque converter with no auxiliary impeller, only one stator, and minus the weird secondary coupling blades. I think the stall speed was lower as well.

Also, I got a chance to leaf through an actual 1952 Studebaker shop manual for Automatic Drive, which notes that the gear ratios were 2.31, 1.44, and 1.00, with a converter stall ratio of 2.16:1, giving a starting ratio in Drive of 3.10:1. (The introductory text is as cited in your text, which I guess was a matter of rounding it off for conversational effect rather than precise specifications.)

What a great piece! I had known that this transmission was unique among early automatics, but you have dug far deeper than I ever have.

One side note, after Studebaker moved to the cheaper BW in 1956, its main difference from the Ford O Matic was that while Ford used what became the modern shift quadrant (PRNDxx) Studebaker used the GM standard (PNDxxR) and would continue to do so through the end of production in 1966.

I can still recall my shock, consternation and fear that I had “broken something” the first time I floored the gas pedal, mad about something unrelated to the car, and my automatic transmission equipped ’53 Studebaker Champion Regal Starlight Hardtop hauled azz (compared to before) from a stop light! This was my first “slush box” car; having always had 3 or 4 speed cars in the past.

The TorqueFlite automatic in my Mom’s station wagon didn’t shift like this; I was convinced I had destroyed the tranny; was wondering HOW I was going to pay to get it fixed on my $2.10 hourly wage at the TG&Y store.

Concerned & confused about what happened, I asked a older car guy friend about it.

He just chuckled and told me that I had finally experienced the first gear acceleration of my Studie! All the time before the car had been starting off in second gear…and I didn’t know it!

Compared to the smooth, graceful (but slightly leisurely) second gear take offs, the low gear acceleration was like driving a V8 Cadillac.

I started manually selecting low gear, then shifting to drive (for the normal second and third gear upshifts) most of the time after that. The manually selected first to second gear upshift was slightly firmer/harsher than the second to third gear upshift…..but being a speed obsessed 22 year old I put up with it.

Fascinating article, Thank you!

+1

My XB Falcon goes with a BW35: strong, smooth, reliable… the best

Great article – very informative. As an AMC fan, I was somewhat familiar with the Flight-O-Matic but this helped fill in a lot more details.

Always enjoy seeing these tech histories on CC, Paul! Thanks…

Automatic transmissions are an evil invention.

ll this is interesting, but I have only one two part question. Will the DG transmission fit on to my 259 engine in my 1956 Studebaker power hawk and will the fordomatic also fit to my 259 Studebaker engine.

Good question, Charles. My uneducated guess is that the DG should mate to a 259 because they came together in 1955. But for someone who may actually know for sure (and for the Ford-O-Matic compatibility) you might contact the Studebaker Drivers Club that has an active technical forum. Those guys ought to be able to answer your questions.

The dealer stamp on the Studebaker brochure at the beginning of the article- Goodwin Park Garage is a dealership locale I do remember. I didn’t know it as a Studebaker store but do remember it as an early one car showroom Toyota dealership, Goodwin Park Toyota. It is now a CVS.

Looking for planetary gears for a 1966 Jag with a BW DG250 automatic gearbox6.These trannys used in Studebaker and Jags.