For many years, starting with the advent of the electric flashing turn signal, the front indicators emitted white light by means of a colourless incandescent bulb behind a colourless lens of one sort or another. This was in keeping with a longstanding colour convention of white for front lamps and red for rear ones. This is an account of struggles toward rectitude in front turn signal specifications—the rear ones will have their turn, but not today.

In 1958, the (U.S.) Society of Automotive Engineers undertook a practical study of turn signals. In case you think that sounds all rigorous and scientific and stuff, it means the SAE Lighting Committee held meetings where they peered at cars equipped with a variety of signal configurations, and committee members voted on which setups they thought they liked best. One of the outcomes was a consensus that front signals ought to be amber, the better to be discerned against reflections off chrome during the day…

(They had a point, there; did you see this ’52 Chrysler’s white turn indicator before I mentioned it?)

…and against white headlamps at night. In theory, this recommendation wasn’t radical and caused no real disruption; in 1957—and probably quite a few years earlier, too, but 1957 is the oldest version I have—the SAE standards for both turn signals and parking lights already specified “white to amber”, a term still in use which means white or amber (as technically defined) or any shade in between. But practically, the push for amber front turn signals in the United States caused some serious friction; giant headaches, vociferous opposition, and dubious marketeering.

At the time, you see, there was no national, nationwide regulation of vehicle equipment, design, construction, or safety performance. That didn’t come in until the advent of the first Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards on 1/1/1968. There wasn’t even any legal structure in place for national regulation of vehicles, nor was there any federal agency with the authority to regulate motor vehicles, until the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966 established the U.S. Department of Transportation and three relevant agencies: the National Highway Safety Agency, the National Traffic Safety Agency, and the National Highway Safety Bureau. These three agencies were consolidated into the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) by the Highway Safety Act of 1970, but now I’m getting ahead of myself; the main thing is it was not possible for the US Government to require or specify anything in the way of vehicle equipment or design. That was left to the individual states, and most of them required type-approval by that state for each and every lighting device to be offered in that state on or for vehicles. And this was without any reciprocal recognition, so automakers had a giant amount of paperwork to do to get all their cars’ various exterior lights approved by each and every state in time for each new model’s first sale. Same for aftermarket repair and accessory parts. (funny, I don’t remember reading anything about this costly, unwieldy, restrictive, perpetual nuisance in the buff books’ screeds and jeremiads against federal regulation of vehicle design and construction).

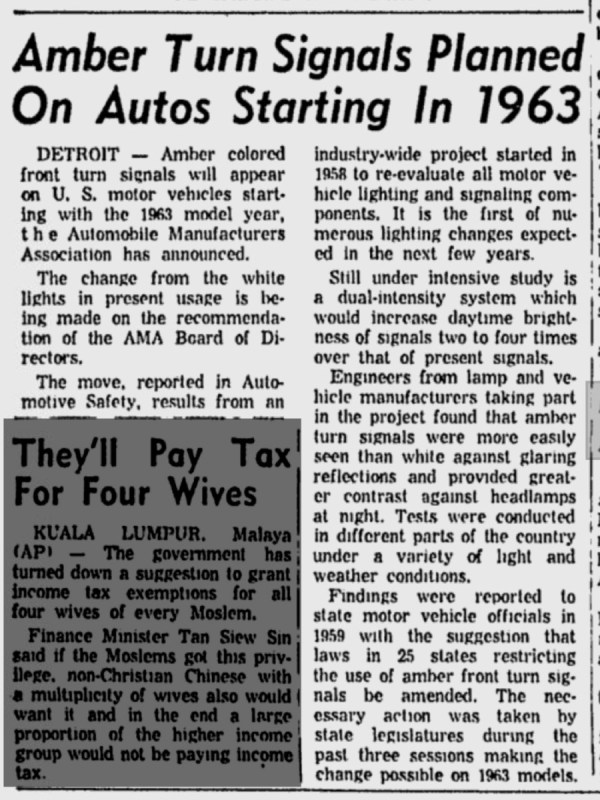

It wasn’t a complete patchwork mishmash, for there was some coöperation among the states loosely coordinated through a series of associations of state motor vehicle administrators; a series of automaker associations, and (at a distance) SAE. 25 of the 50 states required white front turn signals and/or parking lights, and back then there was a quaint custom of states actually—sometimes theatrically!—enforcing their vehicle regulations. So 25 states had to be coralled, cajoled, and convinced to change their laws. This typical article from the Tuscaloosa News on 24 January 1962 politely elides the enormous amount of sausagemaking involved; it reminds of that scene in “The Great Dictator” when Charlie Chaplin’s “Adenoid Hynkel” character shouts out a bunch of scornful, hateful pseudo-German, then the translator says His Excellency has just referred to the Jewish people:

By and by and by, all the states got onside; amber front turn signals were now legal throughout the land. This, however, was much closer to the start than to the end of the problems. In that era of the annual model change, being seen to have this year’s model rather than last year’s was a very big deal. Legislative catscratches and bites were still being bandaged when aftermarket amber turn signal conversion products popped up like mushrooms on cowflops. One reputable outfit—Peterson Manufacturing, still a going concern making top-notch lights in Grandview, Missouri—offered a product they called AmberTurn. It was a little brush-in-cap bottle of transparent amber paint formulated to adhere reasonably well to plastic and glass. I would like to show it to you, and so would the Peterson people, but it’s missing from their archive and I haven’t found any promotional material (yet; I’ve only been looking since 2015).

So here’s a small sampling of the other offerings. Many of them were flexible amber filter “gels”, as the theatrical-lighting industry calls them, trimmed (more or less) to fit between the bulb and the lens. Here’s a sample ad for probably that kind of conversion:

Others were described to sound like amber plastic balloons to clip onto the bulb behind the lens—this one from the February 1964 issue of The Rotarian claims also to “increase the light magnification”. I’m so sure.

Some were similar to Peterson’s AmberTurn, like this one (Popular Mechanics, April 1963):

And still others were…well, that is a very good question, and they’re certainly glad you asked it! (also from the April 1963 Popular Mechanics):

There were probably a lot of poorly-informed homespun efforts at conversion, as well; orange paint in a spray bomb (as aerosol cans were still known at the time) was as close as your nearest paint or hardware store. But remember that quaint custom I was talking about? You could get a whole lot more than just an actual, real ticket for monkeying with the lights on your car; just wait til you get to the end of this article from the Reading (Pennsylvania) Eagle, 23 March 1963:

(‘What colour is amber?’ was never actually a puzzle or problem in all of this; its technical definition had been established by SAE for decades.)

Arrested‽ Wow, the past is a foreign country. Could wish the same attitude were applied today against the likes of “HID kits” and “LED bulbs”.

There were probably some replacement lenses offered in amber rather than the original clear, such as the ones on this 1960 Pontiac (which left the factory with clear lenses in front of clear bulbs):

But now wait a minute here; okeh, paints and gels and clip-ons and suchlike might have given less-than-good results, but—aside from it being an arrestable offence in at least Pennsylvania—why not just replace the clear bulbs by amber ones, the same 1034As used on 1963 cars with clear lenses? Well, it turns out those Pennsylvania police weren’t quite so rabidly overdoing it as it sounds. The first amber bulbs looked as though they’d been through a school bus or taxicab paint booth:

The coating was a high-temperature translucent paint that went on thinly and stayed on the bulb for awhile if you were very careful not to scratch it during installation. They worked well enough to pass muster with the various states’ type-approval authorities. But translucence is not transparence, and that made optical problems. If you wear eyeglasses, imagine how well you’d see with Scotch tape over the lenses. You’d still know light from dark and red from yellow from green, but details? Nope. Most turn signals of that time used fresnel lenses: a magnifying bullseye aligned with the bulb, with concentric rings around the bullseye—like the lenses in the first pic of this post. All these optics were designed to look at the bright line of the filament, and magnify and spread its light. Replace the bright, sharp, fine line by a diffuse big ball, and yeah, turn signal output was definitely going to suffer.

That technical detail, however, was not the bee in the bonnet of one Merrill J. Allen, O.D., Ph.D., an optometry professor at Indiana University. He had a big ol’ hate-on for amber front turn signals right from the start, based only on the reduction in intensity caused by the colour filtration involved, whether on the bulb or in the lens. The scientific thing would’ve been to set up and run some experiments, but instead he just summarily decided what conclusion he wanted to be true—white turn signals are better—then went trying to justify it with incessant blather and irrelevant answers to other questions. There was no substance to his campaign; it was nothing but his guesses and pet ideas about just one of numerous factors that determine the conspicuity and safety performance of something like a turn signal. It’s difficult to imagine being able to accumulate his degrees and get to his position without knowing he was ignoring and violating completely basic principles of scientific understanding, and yet he bleated and hollered, at his every opportunity, that everyone else and all the research was wrong. Much like saying It’s chilly out today, so there’s nothing such as global warming.

Any kind of colour filter is going to reduce the amount of light emitted by the bulb; that’s what filters do, and that was understood and accounted for from the start of the whole thing. The light output spec for the amber bulbs was (and still is) 25 per cent less than for a plain bulb. But such was the volume of Allen’s squawking that the Automobile Manufacturers’ Association felt compelled to respond defensively. Here’s what the NADA said about it in their February 1965 magazine:

That didn’t stop Allen. Here, take a look at his spittle-flecked insistence that he’s right. See how much crap he flings, desperately trying to make some of it stick (left column), and note the professionalism of the researchers in their rebuttal (right column; TLDR highlighted):

The illustrious Doctor Allen (O.D., Ph.D!) made a couple more contributions to the vehicle lighting literature, and most of them were of no import in the long run. Doctors Mortimer and Olson, on the other hand—the researchers Allen tried and failed to torpedo—both had long, productive careers in the field. Their research was and is respectable because it was scientifically sound; they thoughtfully designed and carefully carried out experiments to answer questions, then reported the results without any mention of whether they lined up with any personal preferences or pet guesses. That’s the right way to do it, and you can see them in action here in the work that made Allen’s head explode: in 1966 they methodically studied the conspicuity of turn signals at various distances from lit headlamps and shiny chrome using colourless bulbs; the painted amber ones, and the then-new transparent “Natural Amber” NA bulbs. Click the first page here for the whole paper as published in Traffic Safety, put out by the U.S. National Safety Council:

Alright, so it was well and truly settled: amber front turn signals really are better than white ones, especially when the whole optical line of sight is unclouded (see-thru amber bulbs with clear lenses, or clear bulbs with amber see-thru lenses). But there were more flies in the ointment. Prior to the colour change, many vehicles around the world had, on each side, a single bulb with one bright filament for the turn signal function and one dim filament for the parking light function. These reciprocally-incorporated park/turn lights were discontinued when most countries adopted amber front turn signals, because those countries stuck with white front position (“parking”) lights. The 1968 Geneva Convention on Road Traffic, in specifying amber for all turn signals and white for the front position lights, defined a modification to the colour convention: still white to the front and red to the rear, but now amber to the side. Turn signals, intended to advertise lateral movement, were placed in this side category rather than the front and rear categories.

If there had to be two colours instead of one, there also had to be two lights instead of one: amber turn signals and white position lights on the front of the car, each with a single-filament bulb providing only its one function. Often the white front position light was incorporated into the headlamp by dint of a small bulb protruding through a hole in the headlamp reflector a short distance away from the main headlight bulb. This kind of front position lamps are still with us; they’re called “city lights” by Euro-fans for reasons to be explained in another post one day. They were easily implemented in the composite headlamps used in Europe, but sealed beams are, erm, sealed—no way to make a hole in the reflector without ruining it.

So the British sealed beam industry figured out a workaround: they provided about a one-inch circle of unreflectorised area below the filaments. The reflector was made of pressed glass, so this meant a small see-thru window. A stamped metal cup was cemented to the back of the reflector, centred on the window, and a small bulb was socketed into that cup. That bulb’s white light shone through the circular window and bounced around inside the sealed beam, providing a white front position light. Here are Lucas sealed beams showing the window and the reflector cup:

If the American industry knew about this solution at all, it made them laugh or scream or both: Are you nuts? That’s going to add cost! Why, they’d have to change the wiring harness; the headlamp buckets; the sealed beams themselves…that’s a flat no! What are you, anyway; some kinda commie‽ (To be fair, there was one valid argument against this solution: removing reflector area reduces the amount of light produced by the headlamp—a bigger concern with smaller headlamps than with bigger ones.) As previously mentioned, the SAE standards called for “white to amber” parking lights, so when turn signals changed to amber in America, parking lights came along for the ride. Most vehicles still had the single two-filament park/turn light, just now in amber. That brought some new concerns. Take a look at this what an outfit called the Automobile Legal Association came up with as reported in Product Engineering on 23 December, 1963—amber parking lights look too much like red tail lights:

H’mmm. That’s an interesting question, and a bit of an unsettling one. I’ve looked, but I’m not aware of any methodical research into whether amber parking lights present this or any other significant hazard—I’m guessing probably not really, though they break the white-front/amber-side/red-rear convention—but Consumer Bulletin picked up and ran with this in their August 1964 issue:

This concern fizzled out; amber parking lights remained allowable and common in North America; allowed but not common in a few other countries, and banned in Europe and most other countries. In the long run, Europe’s rejection of amber parking lights wound up benefitting motorcyclists; about forty years after all this kerfuffle, the European regulations—by then applied in most of the world outside the North American regulatory island—were changed to allow (only) motorcycles to have amber front position lights. The idea was to give motorcycles better conspicuity as motorcycles in nighttime traffic. A fine idea, likely good for safety, but we can’t do it in North America because all vehicles are allowed to have white or amber parking lights, and motorcycles aren’t required to have any at all.

But wait! There’s more!

It seems even after all the states got onside and changed their statutes to permit amber where only white was allowed before, some of them backslid and refused inspection stickers to some cars with clear lenses and amber bulbs. The 1964 Studebakers started out using clear lenses and amber bulbs, then the factory changed back to the 1963 arrangement of clear bulbs with amber lenses to placate those states. Take a look at this Studebaker service bulletin from April 1964:

Now, something doesn’t quite sit square with me about this. Studebakers were far from the only 1963-’64 models with the clear lens/amber bulb arrangement. There was never an amber version of the 1963 Plymouth park/turn lens, for example; only clear ones, with those 1034A amber bulbs behind them. Chrysler never issued a service bulletin or amber lenses for those, and I’ve never heard or read stories of ’63 Plymouths flunking inspection on account of clear lenses, number one. Number two, recall that in those days before federal regulation, each and every lighting device had to be type-approved by each and every state. Those states had approved those Studebaker and Plymouth lights, clear lenses and all, otherwise the cars wouldn’t have been offerable for sale there. My best guess, given Studebaker’s tiny sales volumes, is that a small handful of owners got hassled by poorly-trained inspectors and complained to Studebaker, who misreacted as described in the bulletin rather than cordially inviting the states to perform certain specific anatomical impossibilities. [Update: see comment below by Rob, posted May 8, 2022, for another perspective on why Studebaker owners might’ve been singled out for harassment]

So that’s just about the whole story on how amber front turn signals came to America. Most of Europe changed to amber without any fuss in 1967-’68, but Italy did not; Italian national regulations carried right on specifying white front turn signals. But Italy had also been one of the first countries (if not the very first) to require side turn signals, likely due to that country’s heavy population of bicyclists sharing narrow roads with cars. Side turn signals had to be amber, but front ones in Italy had to be white. Some automakers chose to install separate amber side turn signal repeaters as would eventually become common throughout Europe and much of the rest of the world, but that was not the only acceptable option; if the front turn signals had sufficient lateral light distribution, they could also serve as the side indicators—but they still had to produce white light to the front and amber to the side.

Automakers and their lighting suppliers devised some clever solutions to do just that. Front turn signals with enough wraparound had transparent amber lacquer applied to the outboard extent of the lenses or an amber section of plastic moulded in, so one colourless bulb (or sometimes two of them) provided a white front turn signal and an amber side turn signal function. Let’s have a diaporama :

This is the only picture I’ve ever found of the exceedingly rare Italy-spec Volvo 164 front park-turn lights.

Porsche 911, Italy: inboard white front position lamp; outboard white turn signal, amber wraparound for side turn signal

An especially interesting case is that of the VW Beetle, which had not only a special white/amber lens for the front + side turn signal, but also an Italy-specific turn signal housing. It was similar to the chromed metal housing used elsewhere, but with a window in the outboard wall exposing a portion of the elsewhere-covered part of the lens, which was lacquered amber:

The Italian requirement for white front turn signals remained in force until 1977, when Italy adopted the amber front turn signal that had by then been common throughout the rest of Europe for most of a decade.

So, what lessons can we draw from this giant kerfuffle over what seems like a triviality?

• Some good lighting that probably improves traffic safety doesn’t make it beyond statutory borders, and sometimes falls victim to regulatory blind spots. The Italian windowed VW Beetle turn signal is obviously superior to the rest-of-world unwindowed item, and it could just as easily have been used with an all-amber lens. But a basic tenet of the European (later UN) vehicle regulatory system is that anything not explicitly permitted is prohibited, so the Italian turn signals couldn’t be installed elsewhere.

• It can be difficult to optimally and finally assign light colours even when there’s an overspanning colour standard such as white front/amber side/red rear. Turn signals, over the years, have migrated from being considered front (white) and rear (red) lights to being treated in most countries as lateral (amber) lights, and research as well as most of the world’s consensus supports the latter view—but at a philosophical level, both arguments are cogent; one can just as correctly argue either that front and rear turn signals are front and rear lights, or that turn signals are to advertise lateral motion and therefore count as side lights no matter where they are mounted.

• There is very little new under the sun (or moon); Japanese automakers, in the ’80s to early ’00s, tended to put white front position lamps at the front corners of the vehicle, outboard of the headlamps and wrapping round to the side. To meet the unique American-market requirement for front side marker lights, they often simply coloured amber the outboard portion of their rest-of-world front position lamp, in a close reprise of the old Italian technique. This Camry item uses a single clear bulb casting white light through the clear lens to the front; amber light through the amber lens to the side:

So, at long last, I hope that’s all clear (er, amber)!

A very entertaining and informative read—which reminded me how little I’d known about this all these years.

I went looking for *something* about Amber-Turn, turning up only a 1963 ad in some Oklahoma paper:

Hey, neat! I wonder if that’s the Peterson product or some other being sold under the same rather obvious name. Seems one can replicate this tiny slice of the past, particularly those partially-lacquered Italian-spec lenses, with the likes of this Tamiya model paint:

Yet another (PM, Jan. 1963)—likely you have it already. Even $2 was not trifling in 1963:

Hey, lookit there. Must’ve been scads like this. That’s $18.79 in today’s money.

That Tamiya’s great stuff, and I use it almost daily.

But how about the stains sold for stained-glass work in craft stores? Before this Tamiya colour became available, I used to use ‘Great Glass” glass stain on my models. A neighbour’s old EJ Holden ute had badly faded rear lenses (because Australian sun), so I painted his (on the inside) with this (did his brake lights lenses red as well, while I was at it), and wound up doing a few other folks’ cars as well, on his referral.

It looked good, but now I kinda get the feeling that the actual amount of light transmitted may have been reduced. But at least the police got off his back about faded lenses.

I’ve never done a practical comparison of lens paints. Some of those faux-stained-glass products might work; the trick would be getting the right colour. Orange is likely to be too orange; yellow too yellow. A mix of the two might be just right. Red is highly likely to be too violet.

Yes, the amber was definitely ‘oranger’ after my treatment, but we thought it was cool. 🙂 We didn’t notice the red being different, but undoubtedly you’re right.

Hey, that doesn’t look bad! I mean, I can’t see what it looked like lit up, but from this view they look good.

I need some of that. The rear turn signal lamp on one of my cars (it has a water-white lens) has the amber flaking off and shows white to the rear! But with my luck, I’ll paint it and then the bulb will burn out.

Why not just install an amber bulb behind the colourless lens?

As a keen modeller (just a cover for the glue sniffing) I used Tamiya model paints to re colour the the faded tail lights in my bride’s Datsun 200B.

Thanks; I learned something (or two) this morning. It’s fascinating how a rather obvious better idea can face so many hurdles to adoption.

Love those Italian VW Beetle items. And I never fail to be impressed by all the old articles and images you come up with.

Never underestimate the ego of someone who either wants it done their way, or, will insist on his particular modification to an already accepted standard. For years I’ve been involved in rule making bodies of various hobbies, and long learned to dread the person who’s decided that the world will stop completely if they can’t make some modification (no matter how minor) to an already accepted system that they can later point to and gleefully say, “That’s my work!”

Y’welcome and thanks, Paul. I’m not involved in the Beetle scene, but looking in from the outside, these Italian front turn signal housings are prized items—as are the ’59-’60 Italy/Australia-only taillights.

Awesome article Dan. As to parking lights I find it interesting as I had several mid 60’s Chevy pickups some of which would have the parking light on with the headlights and some would kill the front parking lights when the headlights were selected. I remember the NA suffix bulbs as having a more yellow and opaque color than the bulbs with the A suffix. As of late I have noticed a lot of later model vehicles with white front turn signals because the A coating flaked off. Another peeve of mine is a lot of cars out there have the turn signals too close to the headlights and are completely overpowered by the headlights at night. Thanks for the great read.

Thanks, Erik!

On (most) pre-1968 vehicles, the parking lamps do not remain lit when you turn on the headlamps. You can see the parking lights briefly blink on as Gene Hackman pulls the light switch of a ’64 Plymouth through and past the park/tail position in switching on the headlamps:

For 1968, this was changed so the parkers stay lit with the headlamps for safety—with a burned-out headlamp you still have at least some light visible on the burned out side of the car, so other drivers don’t mistake you for a motorcycle. This is easy to retrofit by jumping the parking light and tail light terminals or wires near the headlight switch.

The “NA” suffix means “natural amber”, and refers to amber glass. “A” was for amber coatings—first those opaque-looking yellow ones, and more recently various transparent amber coatings, some of which are adequately heatproof and others not (as shown here).

The regs require turn signals close to low beams, DRLs, and fog lamps to be brighter than those mounted further away have to be, but you’re right; some signals are still hard to see when they’re too close to other lights. The one real benefit of the relentless drive toward bluer and bluer headlamps is the increased colour contrast with amber turn signals.

If you slow down the video of Gene Hackman’s ’64 Plymouth, it’s only the driver’s side turn signal that momentarily illuminates. I’m going to guess that the passenger side bulb was burned out.

You sir are a professor of automotive incandescence 👍

No fair, you’re only sayin’ that ‘cuz it’s true! »stamps foot«

There was a bulb made for the 90’s Jeep Cherokee called the 3454NAK…. The brightest Amber turn signal bulb ever made because the turn signal got washed out being so close to the headlight. Chrysler needs a fix yesterday once they found out so a 50cp filament from a clear wedge was wrapped inside some GE Cadmium glass to make a miracle maker.

If only I saved a few…

Yup…and you and I are probably close to the only people in the world who know why it was called the 3454NAK. You because you named it (dintchya?) and me because you told me!

What a great bulb it was. I saved a few. But I believe I told you that. A 3457NA (what everyone replaces it with) just doesn’t pop like the 3454NAK in the Grand Cherokee. That’s the main reason I never switched the front harnesses to bayonet base like the rear. I have a couple of boxes I bought from Chrysler before they went away. When I turn on the turn signal at night you can see it flashing quite clearly on distant signs. They can be found on eBay but at insane prices. They were quite reasonable when Chrysler was selling them. I like that bulb!

Interesting, Daniel. Thank you for presenting this.

I have the first model Hillman to feature amber front turn signals Lucas fitted an amber lense in front of the bulb inside the sidelight casing and added a smaller park light bulb consequently those park/indicator lights only fit the MK4 Superminx, which is ok I have several spares and NOS outer lenses, that puts the adoption of amber front turn signals about 1966 for the UK market, Ive previously owned 65 UK sourced cars that still ran clear front turn signals.

Right you are. In the UK, vehicles first used before 1 September 1965 could have white front and red rear turn signals; vehicles first used starting on that date had to have amber front and rear ones.

Australia mandated amber turn signals at the front for 1973/4 by which time the entire planet was using them so their local cars now matched anything imported

You must be right, because I can picture heaps of HQ Holdens (new in ’71) with woeful little pale white winks way down in the forward-tilted (thus visually downward-facing) chrome bumpers. At least the ’70’s Falcs and Vals had theirs nicely high up, and out on the edge too.

Australia’s best unique idea was allowing amber rear turn signals to double as reverse indicators in response to manufacturers’ pleas not to pile on too many separate mandatory lights, rather than the American solution of red stop-tail-turn and clear/white reverse. That way, no lamp carried more than two functions and the only ambiguity was in one specific low-speed circumstance (backing into a parallel parking space without first canceling the turn signal) rather than a very common high-speed one (signaling a turn while applying brakes to slow down for it).

I agree with you 100 per cent; Australia’s functional piggybacking was much smarter than America’s. I did up my truck that way.

I don’t think amber combination reverse/turn lights were unique to Australia, though. France and some other countries allowed amber reversing lamps in the past, and at least in some of them the regs were probably written or interpreted such that this combo was allowed. But it was by far more common in Australia than elsewhere, probably because for many years US-sourced or -influenced car designs were the most popular—GM Holden, Ford, and Chrysler had the lion’s share of the market—and most of those designs accommodated two light compartments on each side, but not three.

Interesting. Holden had three-compartment tail lights on the ’59-’62 FB/EK models, then retreated to two-compartment thereafter, until the first Opel-based Commodores.

We still live with this backing and forthing on the North American regulatory island: real (amber) turn signals one year, separate red brake and turn signal lights a year or two later, and then red combination brake/turn signals after that, back and forth and all around on any given model as a matter of style and pennypinching.

In Oz the turn signal had to be switched on before commencing to reverse into a parking spot. You got used to seeing cars reversing with the left rear amber light blinking and the right one shining constantly.

Justy they kicked in at the same time as metric speedos, VJ Valiants and XB Falcons had the new amber indicators,

It seems funny now but in the late 60s you could buy in Aussie a Holden without a heater but it would have fan forced demister as per ADR regs you could not get that in NZ heaters were standard as Holdens had to compete with other cars of similar spec often in the same showroom so carpet heaters and power assisted front disc brakes became standard issue.

Intriguing question about why Studebaker had to issue guidance on changing lenses in 1964 while other manufacturers didn’t.

The timing of the US clear-to-amber change coincides with a significant change in the US/Canadian auto trade.

After December 1963, all Studebakers were imports to the US market. Studebaker had long had Canadian production, but like other manufacturers, the Canadian production was intended for the Canadian market rather than for the US market.

In the early 60’s lacked scale, Canadian auto worker wages were roughly 70% of US auto worker wages. What most quoting this statistic fail to consider is the importance of mass production scale to end costs. In the early ‘60s, Canadian manufactured cars were significantly more expensive to build despite the wage cost advantages. Canadians paid more for their lightly disguised US cars because those cars cost more to build in Canada.

The reason US automakers even bothered to assemble cars in Canada was to avoid Canada’s 17.5% on imported cars. Canada’s high tariff had the intended effect. It led to the development of local auto assembly. The unintended consequence was that as auto manufacturing as an industry continued to develop, Canada’s lack of scale failed to incentivize the continuing investment in scale increases necessary to reduce costs and remain competitive. Canadian scale actually decreased due to the decline in British Commonwealth sales which partially undermined many companies’ Canadian manufacturing investments.

The importance of auto manufacturing to a country’s overall trade balance in the 1950s and early 1960s was significant. Canada recognized they had to change. To their credit, they also recognized that tariffs alone weren’t the answer.

In 1962 Canada’s solution was to increase certain tariffs to 25% on select key imported components coupled with an offer of duty remission on exports. The intent was to incentivize manufacturers to invest in increasing Canadian manufacturing scale beyond the levels that could be supported by relying solely on a protected Canadian auto market. Canada thought – correctly as it turned out – that a combination of free trade, US market proximity and wage cost advantages would lead to increased investment in building competitive manufacturing scale.

What Canada saw as an advantage, US suppliers saw as a threat. US parts suppliers sought a ruling from the US Treasury that the Canadian duty remission was in fact an industry subsidy illegal under US law.

As the calendar turned to 1963, Canada’s tariff remission plan into a political hot button issue for US states having auto part suppliers. It is probably no exaggeration to say US-Canada auto trade tensions were even higher than US-China trade tensions today.

Experts on both sides seemed to have a consensus opinion that any forthcoming US Treasury would classify the tariff remission as an illegal subsidy.

As can often happen in such matters, politics intervened. Treasury slow walked the investigation necessary to issue a ruling. Meanwhile US and Canadian negotiators used that time to draft an agreement that became known as the Auto Pact. It went into effect in 1965.

Today the Auto Pact has been largely superseded by subsequent international tariff and trade agreements. While it lasted, it did build up the scale of Canadian manufacturing to world competitive scale. Given the effect on industry, it is something probably worthy of an entirely separate article by economic experts more knowledgable than I.

So what does this all have to do with poor Studebaker? Here’s my speculation. The shutdown of US Studebaker production must be looked at through the emotions at play during the time it was occurring. US-Canada trade tensions over boiling over due to US fears of the effect Canadian auto tariff remissions. In some quarters, Studebaker’s decision was viewed as a portent of the future.

Who can say how these tensions might have manifest themselves in decisions by various states to single Studebaker’s car imports for special scrutiny?

Wow—thanks for this. Your speculation seems plausible. I didn’t know any of this what you describe about the events leading up to the Auto Pact. You left some meat on the bone there where you said the Auto Pact has been largely superseded; it was felled in 2001 by a World Trade Organisation ruling that it was illegal. That, I find fascinating: the world’s largest (at the time) auto industry and market, the integrated US-Canada one, was built on an illegal foundation.

It looks to me as though the Auto Pact was designed, in part, to keep Canada under the US thumb (or to punish Canada for having the audacity to, um, exist; poTAYto/poTAHto): I’ve not read the agreement, but I understand it prohibited Canada pursuing free trade in automobiles other than with the United States.

Also curious that Studebaker gives instructions for Larks (which they still sold in the U.S.) and Avantis) which they no longer made, though a low-volume specialty company was being set up to continue production) and Hawks and trucks aren’t mentioned at all, which also are no longer produced by anyone though several 1964 models were built. Studebaker stopped making cars in the US in late ’63 and Canada in early ’66, but the company itself continued making other things for decades to come. Parts of Studebaker are still around today (Cooper, Wagner, Federal Mogul) but the last former subsidiary that bore the Studebaker name disappeared in the early 2000s. That’s part of why Studebaker parts remained so readily available after they stopped making cars.

Amber fender-top mounted (“Class A”) turn signals were already legal for trucks, and required over a certain GVW in some states.

I’m also given to understand that Nate Altman’s Avanti company inherited the entire South Bend parts warehouse, which they then sold to the Studebaker Drivers’ Club.

“Class A” didn’t refer to the mounting style or colour, but to the lit area (at least 12 square inches for Class A; no requirement for Class B) and to minimum intensity (250 candela for Class A; 75 candela for Class B). Both classes were specced as “white to amber”.

The Class A lamps could be used on any kind of vehicle; Class B was only for passenger cars, not large/heavy vehicles.

The current US spec is for front turn signals to have at least 11.625 square inches of lit area for vehicles over 80″ wide; 7-3/4 square inches for vehicles less than 80″ wide. In either case, minimum 200 candela for turn signals located more than 4 inches from the low beam; fog lamp, or DRL (minimum 500 candela for those located within 4 inches of those lamps, and for front turn signals used as DRLs).

Thanks for this closer look at the issues leading up to the Auto Pact. Fascinating.

Those same Canadian built US models were exported around the British Commonwealth and we paid thru the nose for those same cars that were not as well equipped as some of the upscale British and Australian cars but you got a V8 engine.

Not always. My ’63 Belair had leather seats, cut pile carpet, heater, power steering power brakes and Powerglide.

Pretty well speced car for the era.

Nice essay, Daniel! 1963 was also the year for two seatbelts mandate in passenger cars, one for the driver and one for the outboard front passenger; and PCV vales positive crankcase ventilation). Cadillac Division decided that Cadillac should not have the “horrendous” look of amber to desecrate their beautiful grilles (sarcasm here), so they had amber bulbs behind complex turn signal lenses that effectively made it difficult to see that oh-so-awful amber color except when the turn signal was flashing.

Thanks, Thomas!

For 1962, by industry agreement—again, there was no structure in place for a mandate—all cars came from the factory with lap belt anchor points for the driver and front passenger. Not with the belts themselves; those were still optional, just with the anchorages: reinforced holes in the floor pan.

No nationwide PCV mandate, either; California required it for ’61 and New York for ’62, and for 1963 it became more-or-less standard equipment everywhere, except for Ford’s backsliding; more info is in this post.

Yeah, Cadillac liked playing with the lights, eh? They introduced their tricky clear-lens stop/tail/reverse light for ’62 and fiddled around with its design in the subsequent model years. But I’m not seeing what you describe in the ’63 Cad front park-turn light. Its amber inner lens makes itself pretty apparent through the colourless outer lens, to my eye:

Personally, on and off, I found the article a bit flashy.

I’ve owned at least two sixties cars with white indicators, and both were just awful at night. On the ’66 Falcon, for example, the light in the bumper lit up with the headlights, and at night, the blinker was thus a barely-noticeable on-and-off rise in brightness. So many toots and near-misses from cars who didn’t think I was turning. I looked into those silly paints in desperation, and even in the late ’80’s/early ’90’s, they were crap!

Possibly because of that experience, I like amber lenses, including their appearance. Why do they have to hide in shame from their function? It’s not like it’s, I dunno, an ugly, dripping dipstick stuck on there. I never understood the late 1990’s(?) trend for manufacturers to update a model by whiting them out. (BMW E39 five series comes to mind).

As for today’s cars, can someone please give Prof Stern a brief stint as President of the World? Not forever, god forbid, he might get Ideas, but just long enough to eliminate every aftermarket LED headlight – and most factory jobs, come to that – and to make adaptive lamps the only items ever allowed on any car ever made. Crap-arse modern lamp installations may as well be back at the weakling white winker stage of auto evolution when it comes to indicators: seriously, I often can’t make them out of the miasma surrounding the over-bright or too-integrated headlights.

I actually did indeed enjoy the article, sir, and the effort behind it (as per). Blinking good stuff, in fact.

Thanks, JB. Yeah, I don’t want to know about limitless power; just make me Supreme Lord High King of the World for a day or two as regards vehicle lighting. Long enough to fix it, then I’d put down the magic wand (or would it be a turn signal stalk?) and leave it at that.

You make a good point: amber lens/clear bulb works better than clear lens/amber bulb, because the latter is more easily rendered invisible by sunlight. That’s been studied. It might or might not apply to LED turn signals; as far as I know that hasn’t (yet?) been studied.

I’ve also come to prefer amber lenses after seeing WAY too many “amber bulb behind clear lens” vehicles where the OEM bulb coating had faded, or a clueless owner had installed clear replacement bulbs.

I blame the late-1990s/2000s trend on Mercedes: Seemingly 30 seconds after amber bulbs finally won ECE approval in the early 1990s, their stylists worked overtime to redesign the W124, W140, and R129 to have clear-lens signals all around. It was a blatant prioritization of style over function, which the company of the 1970s would never have done. And the rest of the industry followed…

Yup, exactly. And those corrugated signal lights Mercedes used in the ’70s-’80s really were better; the signals they produced remained visible even in bright sunlight.

“One of the outcomes was a consensus that it would be better for front signals to be amber, the better to be discerned against reflections off chrome during the day.”

It’s rather fitting that this happened in 1958. 1958 was Peak Chrome for American cars.

One other interesting aside to the persistence white front turn signals in Italy is that the early Fiat-based Soviet Ladas had Italian home-market style lighting and didn’t get amber front signals until a year or two into production. They kept their Italian-style repeaters through the whole run, though.

I can’t remember the last time I read an article on turn signals written by anyone other than Jason Torchinsky…

Thank you Daniel, for the fine article and research. You enlightened me and brightened my day ! Sorry, someone had to write it.

Miss the era when I bought a set of 5 3/4″ Hella H1/H4 headlights from Canadian Tire to replace the ’91 BMW 318iS’s sealed beams. Simple installation, much better lighting.

You’re welcome, and thanks!

I’m a surprised you found Hella conversion lamps at Canadian Tire. I’d be less shocked to hear of (and you’d’ve been much better off at night with) the Bosch or, before that, the “Lucas UltraQuartz”-packaged Carello conversion lamps Canadian Tire sold.

You’re right, it was probably Bosch after all. This was ca. 1995. Reluctantly sold the 318iS to a young guy who converted it to a “328iS” just a few years ago.

The Italian spec explains why there’d been seemly, or so I thought, a random usage of half amber and full amber lenses on the Ferrari Daytona, which are arguably its most defining styling feature.

Since it’s on topic do you know the explanation behind the amber shade differences between the US spec and “European” spec turn signals? The latter are a darker more orange shade, I know they lack the retroreflector on the side as my friend found out with his W124, but the color difference was really distinct

The European (ECE) amber colour box used to be smaller than the US (SAE) box, and the US front turn signal spec requires higher intensity than the European spec. I can’t say for sure because I wasn’t in the product development meetings, but it seems likely the lighter colour was used for the US lamp to meet the higher intensity requirement there, while the darker colour was used for the European lamp to meet the stricter colour requirement there.

(the ECE amber colour box was enlarged to match the SAE spec a couple decades ago)

Very interesting stuff! I loved your take on the IU optometry prof – it’s a good thing nobody today employs their expert credentials to come up with reasons to reach the answer they want. /sarcasm back off/.

I remember cars from that period in the early 60s when the white/amber change-over happened and that it was sometimes with lenses and sometimes with bulbs. But I never knew anything behind the change or any of the drama that accompanied it.

I remember when both 1157A and 1157NA bulbs were sold, with the later being clearing but the two essentially the same. Over time, the scratch-off exterior coating on the 1157A was replaced with interior coating, then semi-transparent coating that made them look even more like 1157NAs. Some auto parts stores seem to no longer stock both types or combine both numbers into one.

I’ve never seen or heard of an interior-coated amber automotive bulb—always only ever exterior-coated. Can you tell us more?

The “NA” bulbs have grown markedly less prevalent for a few reasons: the original amber glass contained toxic cadmium; the cadmium-free amber glass is more expensive, and the transparent amber coatings got better. There are still (cad-free) NA bulbs made, but now that’s confined mostly to applications where a coating won’t suffice—the hot-running high-watt bulbs like 3357/3457, and the ultralong-life bulbs with filaments that might well outlast the coating.

GE was the only supplier of Cadimum glass melts during the 1990’s in the USA. They used to make some nice dark amber color. The 1995/1996 melts were stellar IMO. The problem was that when GM started to use DRL turn signals in models starting in 1997, the color would fall out of the SAE color box after the cadmium glass heated up for continued use at 14V. So when you saw a Vette or Buick coming down the road they were ORANGE going to RED….

So different grades of amber color were developed from a scale of 1-5 with 5 being the darkest. It got complicated with GE melts so the shift was taken to amber paint. Also as Daniel says the ban on cadmium by MY 2000 was in place at GM and the other big 3 (USCAR meetings). The final nail in the coffin came for the original cad glass at that moment when GE said they were exiting the business of amber glass melts.

With the shortened timeline the amber coating was pushed to market and as you can see above was not robust to the daily demands out there in the market. The coatings are now much better +20yrs later but the color will never match those old cadmium lamps. Yes cad free glass is out there but they are a dull brown in color and not a rich as the old ones. Make sure you purchase the NA designation and not A (amber painted). And never use amber painted A in a DRL application. Will not handle the heat.

Now you mention it, I remember the ’96-’00 Chrysler minivans with turn signal DRLs showing damn-near-red light to the front as you describe. Really, bulb-type turn signals used as DRLs ought to have amber lenses—well, all of them should have amber lenses, but especially those.

I owned a 1935 Buick series 50. It had a yellow lens incorporated into the tail light for the turn signals. The Colorado safety inspections said it was illegal, but gave me a sticker anyway. There were no lamps for the front signals.

Good thing I don’t have four wives. Then I would have to pay taxes on them.

It seemed for a while we were headed for amber-coloured rear turn signals as well, but they seem to have disappeared. Personally I thought they were a significant improvement. A gently flashing red turn signal, when red brake lights have already been applied, isn’t nearly as visible, especially in heavy traffic.

That’s the subject for another article. I promise!

I was expecting it to be included in the infrastructure bill that biden signed but it was just adaptive headlights and some other things ..its sad tho…. Amber turn signals at night in heavy traffic are huge help its just adds way more contrast to the sea of red lights and dark background.

Also that would be usefull on semi trailers with white reverse light(they should mandate new wiring for trailers as todays 7 pin doesnt include reverse lamp).

Wouldn’t’ve helped. The infrastructure –

bill– law directed NHTSA to permit ADB (adaptive driving beam) as specified in SAE J3069. NHTSA disobeyed that directive and instead put out a steaming turdpile of a rule, which essentially kicks most of ADB’s legs out from under it. NHTSA-spec ADB is a much more expensive, much less performant system than is allowed in the rest of the world.The quickest way for model year refresh was to just mold an amber lens/clear lamp and vice-versa. When GE melts got less and less the price per glass bulb skyrocketed so some lighting manufacturers also found it less expensive to go with the amber lens/clear bulb combination to reduce costs.

This is really a different topic, but in the ’60s or ’70s Road & Track wrote about a proposal by some American government agency, which ended up never going anywhere.

The proposal was for red, yellow, and green lights on the rear of cars. Red when braking, yellow on trailing throttle, and green when stepping on the gas. They pointed out that the green would need some blue in it for the benefit of people with red-green color blindness.

Not from a government agency, no, but traffic light-style red/yellow/green rear lights were a JC Whitney-level aftermarket fad for awhile, and there have been ideas and proposals—some with merit, most without—to change car signalling systems, including by adding more colours. Green car lights will be in another post.

Dan, another light article you could cover would be emergency lighting used on police, fire, ambulance and DOT vehicles.

I worked for a state dot from 1992 thru 2016. The internal squabbles over light colors was legendary. The division I worked in was the state fleet managing group. When cleaning out files one day I came across published meeting minutes from 1960, there was one paragraph covering the arguments for and against blue or amber emergency lighting. 30-40 years later and still at it. One state was even talking about using green lights. On road trips its one of the things that always catches my eye, what is this state using?

The general argument is that the “public” is so used to seeing amber lights that they don’t pay attention to it. Still despite having a bunch of lights of various colors flashing at them the public keeps running into emergency vehicles, usually the rear end of the emergency vehicles.

There are colour effects, chiefly in how red vs. blue affects observers’ perception of distance to the light source. That has some implications for how emergency vehicles are best equipped; I had a (smallish) part in this fifteen years ago.

Green has various assignments in various jurisdictions. Green = volunteer firefighter is a somewhat common one. But there have been experiments like this one with green lights on snowplow trucks.

Way too many emergency vehicles in North America are massively overlit, out of the belief that more/brighter/brighter/more just has to be better—that’s completely wrong.

They see so many amber lights that they just don’t pay attention to them any more types of arguments are just-so guesses with zero basis in reality.

Speaking of overlit brake lights, is anyone else bothered by the excessively bright brake lights (apparently) allowed on emergency vehicles like ambulances?

I fail to see the benefit over normal brake light illumination other than someone ‘thinking’ it’s a good idea without actually trying it out in real-world situations. Using them as brighter, stationary flashers is one thing, but this seems needless and actually rather dangerous as it’s distracting and/or implies the need for following vehicles to slam on the brakes.

Massively-overlit emergency vehicles are a real problem. This is a portion of a relevant report from earlier this year:

Secondary crashes are a top cause of roadside deaths among firefighters, police officers, emergency medical technicians, and other first responders. Conventional wisdom on emergency vehicle lighting is that higher intensity improve conspicuity and safety. But a new study concludes that’s not necessarily so. Researchers investigated the effects of light color, intensity, modulation, and flash rates on driver behaviur while meeting and passing a traffic incident scene after dark. Brighter lights were judged more glaring—no news there—but only marginally more visible than lower-intensity lights. And highly-retroflective markings may actually decrease drivers’ ability to see first responders working adjacent to their vehicles.

Volunteers drove a closed-course traffic incident scene at night. Two blue, white, yellow, or red lights were mounted on tripods about as far apart as the left and right edge of the rear of a fire truck. A silhouette cutout of a firefighter wearing a high-visibility safety vest was positioned adjacent to the lights. The researchers tested 14 combinations of light color, intensity, pattern, flash rate, and presence of reflective markings next to the lights, measuring vehicle distance to the lights and the distance at which drivers could distinguish the silhouette of a firefighter. They also administered a survey after the driver completed the course. None of the variables tested had a significant effect on ratings of overall visibility of the road scene, but certain factors, alone or in combination, proved interesting:

Study participants consistently judged higher intensity lights as more glaring, but only marginally more visible than lights of lower intensity; lower-intensity lights were entirely conspicuous. The researchers say using lower intensities at night would reduce glare without affecting conspicuity of stationary vehicles in nighttime blocking mode.

Drivers’ rated visibility of lights appeared to be related to the perceived saturation of their color; blue and red lights had the greatest perceived saturation and were judged to be brighter than white and yellow lights of the same intensity. Blue and white lights were rated as most glaring. Yellow and red lights were least glaring. This data suggests red lights for stationary blocking operations may offer the best combination of high conspicuity and low glare.

None of the variables tested caused drivers to move their vehicles either toward or away from the lights, so this test did not affirm or refute a moth-to-flame effect.

When fluorescent and reflective markings were present, drivers did not see the firefighter silhouette until they were closer to it. This was the most unexpected finding of the study. Of the four setups tested, high intensity lights with no markings produced the best (longest) detection distance. High-intensity lights combined with high visibility markings yielded the worst (shortest) detection distance. It appears to be a matter of inadvertent camouflage of the emergency worker by dint of their retroreflective garments degrading the negative contrast by which they would otherwise be effectively seen earlier. This suggests high intensity lights combined with high visibility markings—that more-is-better approach again—may make it more difficult for drivers to see responders on foot at night, even when the responders wear high-viz vests. Further research is planned to determine if lower-grade retroreflective markings will help improve the conspicuity of emergency personnel operating near emergency vehicles and traffic.

Yes! That bothers me as well. Sometimes those lights are bright enough to be nearly blinding when stuck in traffic behind one. Similarly, many buses and other “official” vehicles around here are now equipped with blindingly-bright strobing yellow brake lights. Like you said, in a real-world situation, it’s just simply annoying.

Oh, groan…those new deceleration strobes, which are allowed to be yellow or red. A trucking fleet had such ZOMG AMAZEBALLS giant reductions in rear-end crashes in their little experiment that they put them on all their trucks, even though they weren’t legal, and kept paying the fines every time they got dinged at a DOT inspection. On ‘strength’ of their results, an industry group whipped up a lobbying effort, and suddenly they’re legal. No long-term study to see how much of the benefit was due to a novelty effect, no broader research to determine if there are any deleterious effects alongside the purported benefit, none of that. Just suddenly money –> lobbying –> legal.

(…but oh, whoah, hold on there, turbo; we can’t just go mandating amber turn signals just because there’s six decades of research consistently demonstrating that’s the right way to do it, and everywhere else in the world does it that way; we’ve got to make sure it would be an effective thing to do, and gosh gee, we’re just not there yet, so…)

The irony is that (from the little I know) humans tend to move towards whatever they’ve focused on. So, the idea to make emergency lights even brighter and more noticable would seem to increase the likelihood of a rear end collision.

Simply put, the idea would be to make rear emergency lights ‘just right’, i.e., bright enough to draw attention to them, but not ‘so much’ attention that drivers fixate and subconsciously drive right into the vehicle.

You’ve got the right idea in general—make them bright enough for conspicuity, but not so bright that they make other safety problems—but take a look at the summary, and the linked study itself: that moth-to-a-flame idea was tested and not substantiated.

Thanks for the backstory… I had a feeling it was some kind of irritating story like that.

Out of curiosity, what industry group was it that lobbied for these strobes? I’d assumed it was one of the safety organizations that had pushed these – I hadn’t thought that an industry group would be lobbying for it. Just curious where the money motive lies for a product that to me seems somewhat trivial.

I think it was a coalition of the TSEI (representing makers of products including—gee!—lights and wiring harnesses for heavy-duty vehicles) and a few other interested parties.

Thanks.

One question Daniel are there lighting standards for heavy trucks in North America? I ask because American brand trucks have the most pathetic headlights Ive ever used and yes I have driven 6 volt Volkswagens at night

You very often mention this perceived awfulness of the headlamps on American-brand trucks. Yes, the American lighting regs apply to all roadgoing vehicles. One or more of the following things is driving your experience:

The American vehicle industry for many years prioritised low cost and long service life in headlighting systems. Especially with glowing filaments (i.e., halogen bulbs), one trades off performance for lifespan.

At American makers, some people tasked with specifying the conversion equipment aren’t anywhere near so familiar with the rest-of-world regs and end-user preferences as they are with those in the American market, so sometimes the equipment is chosen just for compliance and price, without much concern for performance beyond what’s legally required. And contrary to fanboy belief, the rest-of-world UN (formerly “European”) lighting standards have way too much room for lousy lights—and so there is a tall mountain of lousy lights that are legal everywhere except on the North American regulatory island (which has its own mountain of lousy lights, because the American standards have too much room for bad lights, too).

Both standards allow for good to excellent lights, too, and North America is not without talent in the field. As I type this I’m thinking of a fantastic American-made LED headlamp in the 7-inch round format so many vehicles round the world have used over so many years. This thing is trouncingly the best 7″ round headlamp ever made; easily one of the best low beams ever on the planet, and its primary market is Australian trucks and road trains. I wish this lamp were available for right-hand traffic, but it’s not and won’t be, which is a damnuisance.

Sometimes vehicles are converted by a third party, whose incentive is to keep the conversion cost as low as possible; there’s a lot of compliant (or pretend-compliant) junk on the aftermarket.

All of the above assumes you’re objectively correct, that the American-brand trucks you’ve driven have actually, really lousy lights. But you might very well be wrong. One of the fundamental problems in headlighting is the large gap between the light drivers want and the light we need. The difficulty is, what we feel like we’re seeing isn’t what we’re actually seeing. The human visual system is a terrible judge of how well it’s doing. “I know what I can see!” seems reasonable, but it doesn’t square up with reality because we humans are just not well equipped to accurately evaluate how well or poorly we can see (or how well a headlamp works). Our subjective impressions tend to be very far out of line with objective, real measurements of how well we can (or can’t) see. The primary factor that drives subjective ratings of headlamps is foreground light, that is light on the road surface close to the vehicle…which is almost irrelevant; it barely even makes it onto the bottom of the list of factors that determine a headlamp’s actual safety performance—by the time anything’s in the foreground, you’re going to hit it if you’re going much above 40 km/h. A modest amount of foreground light is necessary so we can use our peripheral vision to keep track of the lane lines and keep our focus up the road where it should be, but too much foreground light works against us: it draws our gaze downward even if we consciously try to keep looking far ahead, and the bright pool of light causes our pupils to constrict, which destroys our distance vision. All of this while creating the feeling that we’ve got “good” lights. It’s not because we’re lying to ourselves or fooling ourselves or anything like that, it’s because our visual systems just don’t work the way it feels like they work.

European-type (rest-of-world) low beams tend to provide more foreground light and less distance reach than US- and Japanese-type low beams. New Zealand allows both types of beam, almost everything on the road has the European headlamps (Japan adopted the European reg in 2006 after many years of their national standard allowing beams very similar to the European type), so anything even a little different is likely to strike you as odd, and you may not like it because you’re accustomed to driving with different amounts of light in different places.

There’s lots of room for crafting beams with different priorities and engineering philosophies in both standards, so an American optical engineer building headlights to whatever standard is probably going to come up with something different than a German or French or Japanese or Korean or Chinese or (…) engineer. Some of them will do a crap job, but if we discard those, this isn’t a collection of right and wrong answers; it’s a collection of different valid answers.

And that about covers it! 🙂

In the 80’s a lot of people in the U.K. would lacquer their headlamps yellow for driving in France – you could buy a bottle from the AA (Automoblle Association) which came with its own brush, like nail varnish. In the 1960s my father said that lorry drivers in France would either try to run you off the road or drive at you with their main beams on if you dared drive with white headlamps, but by the 80s he was relaxed enough just to use stick-on beam deflectors over right hand drive beam pattern lights and no lacquer.

An article about France’s yellow-headlamp thing is one of the bigger items on my list!

Very interesting read, by all means.

In case you are interested, I have some MARCHAL documentation dating back to the 50’s. I recall reading somewhere that we sticked longer than the others with yellow headlights because our manufacturers were unable to produce quality white bulbs. When going to LHD countries, you had to rotate the headlamp (or the bulb) to get the headlamp beam right.

I love your avatar but prefer the older ones.

Very good article, Daniel! Somehow this sounds like the FDA dragging its feet on approving new medications that would, if legally available, inarguably save lives.

Random thoughts:

1. I was an avid model-builder as a child, and decided I would improve my family’s outdoor Christmas lights by painting the glass bulbs where the original colour had flaked off. Did only a few – they looked awful when lit, the brushstrokes glaringly obvious.

2. Some years ago, Dad really wanted to give me his ’69 Chrysler Imperial, which was pretty much the antithesis of what I would have chosen for myself, but I took it because I didn’t want to hurt his feelings. Many things on the car didn’t work, including the turn signals.

I bought a factory service manual, and discovered that the rear turn signals were intended to be sequential, driven by a “sequencer”, an electric motor in the trunk which had died and was not easily obtainable in those pre-internet days.

Compounded with that, the turn signal switch had died.

I did a bunch of rewiring, including bypassing the sequencer and replacing the switch assembly.

There was a big white “cornering lamp” on each front fender that was intended to illuminate only when the turn signal on that side was activated. It seemed goofy to me that this lamp was intended to stay on solidly rather than flashing with the turn signals. Young rebel (and avid cyclist) that I was, I wired it to flash.

3. What do you think of Chrysler’s practice of having the DRL turn off on the side that’s blinking?

4. Why didn’t the manufacturers simply increase the output of those bulbs whose output would be reduced by an amber lens? It didn’t have to be a compromise between bright or contrasting colour – you can have both.

2. Those motor-driven sequencers are lots of fun to watch working—here’s one of my faves:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ChH–ndoofc

But they’re a nightmare to fix, and even when they’re working, they take a giant amount of power to run. There are now electronic replacement modules that do the job much more efficiently and reliably, and they don’t cost much.

Cornering lamps are not meant to flash. They’re to provide some lateral light so you can better see where you’re turning.

3. A DRL must extinguish or dim down to parking light intensity during operation of a turn signal located within 10 cm, unless the turn signal provides at least 500 candela on axis—the same intensity requirement as turn signals within 10 cm of a low beam headlamp. Other turn signals must provide only 200 candela, which is why it’s long been very common for the front turn signal to be near the high beam rather than the low beam; the lower-intensity turn signals are less expensive to make than the higher-intensity ones.

A DRL may extinguish or dim down to parking light intensity during operation of a nearby turn signal that does meet the higher output spec; that’s at manufacturer discretion. There are at least reasonably decent arguments to be made for both “yes, it dims/extinguishes” and “no, it doesn’t”.

4. Lots of reasons. Remember, we’re talking about the early ’60s here. Many cars still have DC generators with negligible output at idle, and not a whole lot above idle, either. If we wanted an amber bulb that produces the same amount of light as a colourless bulb, our 27/8-watt clear bulb would have to become a 36/11-watt amber bulb. Along with that comes shorter bulb lifespan, which makes service hassles. Also, the increased current draw means we need heavier wiring, a higher-rated switch, and a recalibrated flasher. All of that costs money. And the bulb puts out more heat, which is going to require higher-grade plastics for the lens (more money), and is going to preclude the use of amber coatings on the bulb; they’d have to be made out of amber glass. And if the idea is to countervail the filtration losses, we’d obviously want to do that no matter where the filter is in the system, so we also need 36/11-watt clear bulbs, too, for use behind amber lenses. Realistically, the wrong bulb is going to be used in a lot of cases, which is going to screw with the performance of the turn signal and endanger the wiring/switch/lens as already described. If we try to head off that problem by changing the base keying so only the correct bulb can be used, now we’ve made it more difficult to change between amber and colourless lenses. Big headaches, and unnecessary ones; even the 27/8w bulb can produce turn signals that are quite a bit more intense than they need to be both legally and practically. Doctor Allen was just plain wrong about this.

Dan, apropos of the Chrysler “extinguishing headlight with signal” cars:

I hate them.

The first several times that I saw them, I thought that they were malfunctioning. It took several iterations of the same thing, over a period of weeks to months, for it to occur to me that the uniformity of the phenomenon might mean that the operation was intentional.

It still makes no sense to me. I see a normal-appearing front light array coming toward me in the dark on a two-lane road. Suddenly, one headlight disappears and the area where it used to be begins flashing sharply. It takes a second or two for the thought “What just happened?” to be replaced by the thought “That car is turning.”

Under the wrong circumstances, those one or two seconds could become lost reaction time.

The headlight on the signal side should dim, as you noted was acceptable, not go out entirely, so that the shape of the car remains clear to oncoming traffic.

No other vehicle turns one headlight completely off while driving, for any reason, or ever did, as far as I know. This is an alien semiotic gesture that requires some degree of cogitation to understand, every single time it happens.

Who ever approved this absurdity?

Well, there’s the problem right there. The lights we’re talking about, the ones that turn off or dim down when an adjacent turn signal is in use, are DRLs: daytime running lights. The DRL function might be provided by a separate lamp, or by reduced-voltage operation of the headlamp, but either way is not the same as the headlamp function. And either way, the DRLs are meant for use in daylight. When it’s dark out, or the weather’s bad, the DRLs are not the appropriate lamps to use—with or without the parking/tail/side marker/etc lights. With the headlamps switched on, there is no blinkout or dimdown of any lamp when a turn signal is operating.

The problem here isn’t that the adjacent DRL switches off or dims down; that’s a good thing, for it makes the turn signal more conspicuous in the daytime. The problem is the driver misusing their daytime lights when they should be using their nighttime lights. And the solution is that the driver shouldn’t be tasked with picking whether to use the daytime or nigthttime lights, any more than we task the driver with causing every blink of the turn signal or manually switching on the brake lights when they wish to slow down.

The nighttime lights should come on automatically when ambient illumination falls below a particular, already-known value. Or when the windshield wipers are in use for more than 30 seconds. But automakers babble about “cost” (nope, all the hardware’s already in place; this just needs a line or two of code), and Americans babble about freedumb and libertee (…to cause death, injury, and property damage on the roads).

“With the headlamps switched on, there is no blinkout or dimdown of any lamp when a turn signal is operating.”

Hmmmm… Now I’ll have to watch for that.

I’d swear I’ve seen it on actual headlights in the actual nighttime, but now I’ll have to watch and see if I’m [shudder] wrong.

Seeing a vehicle or two NOT do it would prove that when it does, it’s due to driver error.

I remember my Dad bought one of those little paint kits to paint the clear lenses of then turn signals amber on my Mom’s car, a 1961 Buick Special with a 215 cubic-inch aluminum V8 and two-speed automatic transmission. Why go to all of the trouble, I hear you ask? Well, for a start, clear bulbs were slightly cheaper than the amber equivalent, a big deal in 1962. The other reason was availability. Clear bulbs were much easier to come by than the amber versions. Gas stations and auto parts stores were often out of the amber versions while still having the clear bulbs in stock. Why? I don’t know, but that’s one of the reasons the conversion kits became somewhat popular.

As someone who is only slightly less opinionated than Daniel on lighting I’ve of course got to weigh in.

The strobes. I see them mostly on construction vehicles. I find that the sudden, very bright flash renders me monetarily blind, relatively speaking. I mean it’s not breaking news that if you shine a flashlight in someones eyes they can’t see for an instant. So my momentarily part is done and just about when I can see again, it flashes again. So their solution to safety is to try to blind motorists going by so they don’t get hit? Not the way I’d try to do it…

I have yet to have the misfortune of seeing the “amazingballs” spoken of earlier, though I suspect they would be similar to above. I have seem some cars/light trucks with flashing brake lights, which I find just plain stupid. So my response is to flash my high beams at them if they’re flashing lights at me. Even/even? Any reason they should complain about me doing the same thing they are?

I could happily go on, but I’ll try to save peoples attention. I will mention a curious factoid, I seem do disagree with Daniel a lot here, but we’ve spoken offline and somehow our views aren’t much different on beam control and aim etc.

Whatever, a late Happy Christmas all!

Not always. My ’63 Belair had leather seats, cut pile carpet, heater, power steering power brakes and Powerglide.

Pretty well speced car for the era.