Where did you last see an Edsel? Most likely, it was at a museum or car show. So imagine my surprise when I happened upon this 1959 sedan for sale at a small-town used car lot. The sight of an Edsel for sale got me thinking about the original batch of Edsel dealers. After all, while it’s well-known that Ford Motor Company lost over a quarter-billion dollars on the Edsel brand in one of the 20th century’s biggest corporate flops, the plight of individual dealers who optimistically invested in the Edsel concept faded from memory long ago.

Using this particular car as a starting point, we can briefly retrace the history of Edsel and its dealers, and look at three representative dealers in more detail, examining this often-overlooked aspect of a well-known story.

There’s no easy answer to the question of what went wrong with Edsel. Fairfax M. Cone, an advertising executive who headed the Edsel ad contract, reminisced a decade later that “The trouble with the Edsel was almost everything.” Almost. One of the few well-executed aspects of the Edsel program was how a handful of employees built a dealer network from scratch in just a few months. Those dealers, however, while set up with a solid-looking path to profitability, never stood a chance, as their signature product foundered immediately.

The saga that eventually culminated in the Edsel began shortly after World War II when Ford Motor Company studied adding a new mid-priced car line. Ford – it was thought – had meager offerings in the mid-priced range. Increasing prosperity in the 1950s amplified this concern, as more buyers looked at cars priced above the Big Three’s entry-level offerings. Ford’s existing mid-priced Mercury line captured surprisingly insufficient move-up sales of existing customers. According to the company’s own studies, just 26% of Ford brand buyers who traded up to mid-priced cars stayed with Ford Motor Co. products – a paltry number compared to the 78% of Chevrolet’s move-up buyers who stuck with GM makes. Ford customers simply drifted to other companies’ cars, leading Ford Vice President Lewis Crusoe to remark “We are growing customers for General Motors.” A new car line – aimed squarely this mid-priced market – was considered a remedy to this situation.

In April 1955, Ford established a “Special Products Division” to create a new mid-priced car line to compete with the likes of Oldsmobile and Buick – and these cars were to be made available in under three years. What followed was a staggering $250 million investment, and an expectation of 200,000 annual sales to recover this investment. Given customers’ growing affluence and optimism, that seemed reasonable.

Development advanced quickly and – despite intense public interest – largely secretly. However, in November 1956, one of the first major public announcements about this new car turned out to be rather curious. Ford and its advertising team had been studying what to name the car for months, and the company discarded countless intriguing and evocative names in favor of… Edsel. The Ford family initially opposed naming a car after then-president Henry Ford II’s father, and few others advocated for it either, but ultimately a handful of Ford executives and directors who favored the name gained sway. While meaningful to the company’s inner circle, the frumpy and self-adulatory “Edsel” didn’t exactly spark excitement among most people – an unfortunate misstep, but one that was not, by itself, hard to overcome.

Also in late 1956, Henry Ford II made an announcement that would greatly impact his new car’s distribution, proclaiming that “The new Edsel line will be introduced and marketed by a completely new dealer organization.” Selling Edsels would have been far easier using existing Ford or Mercury dealers, but Ford took a dim view of “dualled” dealerships, preferring instead to style its growing family of nameplates after General Motors, which offered mostly single-brand dealers. This business model, it was thought, would benefit Edsel by providing it with a more loyal sales force. But pursuing this course also meant that, within Ford’s newly-named Edsel Division, a relatively small cohort of employees needed to build a nationwide sales organization from scratch… within about a year’s time.

That task fell to Kansas City native J.C. “Larry” Doyle, who had worked for Ford since 1916, eventually becoming the company’s sales and advertising manager. Somewhat unwillingly chosen in 1955 to become the Special Products Division’s General Sales and Marketing Manager (he didn’t view this as much of a promotion), Doyle nonetheless plunged into the role of creating over 1,000 Edsel dealerships. He performed this job magnificently, though hardly anyone noticed.

Developing a dealer network from scratch was a colossal and complex job. Notably, success hinged upon convincing businessmen nationwide to gamble on a franchise for vehicles no one had seen, or knew about beyond just a sentence or two of corporate-speak. The work to accomplish this feat took every minute of time that Doyle and his small staff had; it was a remarkable bit of business alacrity ultimately betrayed by an unpopular product. But when Edsel failed, it wasn’t because of Larry Doyle.

Doyle’s first mission was to figure out just where dealerships should be. By examining demographics, vehicle registrations, migration patterns and areas of rapid growth, rough maps were pieced together. Ten employees devoted themselves to plotting county-by-county vehicle sales in 60 metropolitan areas. None of these men was an economist, statistician or product planner; instead, they were all salesmen. But their exacting work compensated for their lack of direct experience. By the end of 1956, with a rough outline of where, Doyle moved on to the question of who his dealers should be. But first, he would need to explain to potential dealers just what kind of car they’d be selling. Doyle, of course, knew many details that the public did not, since work had been progressing behind closed doors for over a year – though he could share precious little of it. Chief among those details was what the Edsel would look like.

In the booming, suburbanizing mid-1950s, Ford assumed that “move-up buyers” wanted a distinctive car that bellowed prosperity from every surface. Therefore, Edsel’s designers – citing how mid-1950s cars tended to look similar – envisioned a car readily identifiable at all angles from one city block. The new car couldn’t be too different, though, since it needed to maintain parts interchangeability with other Ford Motor Co. products. Merging these demands necessitated designing distinguishing features on the front, sides, and rear, but on a relatively conventional vehicle.

Designers unveiled their preliminary clay model to Henry Ford II and his select Forward Product Planning Committee in August 1955. A few awkward moments of silence greeted the unveiling, as the small crowd got their first glances of an unusual-shaped grille and other design flourishes… and then applause followed. That applause signified that the designers were on the right course. The future car’s style was then on track to proceed. What that select group of Ford VIPs previewed in 1955 was largely the same design that would appear in showrooms two years later.

As the Edsel’s details coalesced, Doyle’s crew firmed up their plan to recruit 1,200 dealers by the fall of 1957, when the cars were expected to go on sale. To do this, Doyle hired dozens of employees who worked mostly in the field – many of these employees had held regional-sales positions with GM, Chrysler or the Independents (though Henry Ford II eventually forbade Edsel from poaching any more employees from the Independents). This experience helped in talking with, and understanding the needs of, prospective dealers.

These employees traversed their territories seeking qualified future Edsel dealers, but instead of cold-calling or hard-selling, they took a back-door approach. Teams of Edsel marketing staff arranged for meetings with bankers in locations around the country, asking them to point out financially healthy auto dealers or other local entrepreneurs. Approaching recruitment through bankers was shrewd. For example, when the Edsel folks met with new prospects, being able to tell businessmen that they were recommended by a prominent banker gave credence to the Edsel sales pitch. Using the financial industry as a matchmaker made prospective dealers feel honored to be contacted. Just as importantly, local financial leaders saw that Ford was practicing due diligence in selecting its retailers… this favorability would help when new Edsel dealers returned to those very bankers looking for financing.

When prospective new dealers became seriously interested in starting an Edsel franchise, they would apply to one of 24 district offices. Each application was then forwarded to one of five regional offices, and finally to Dearborn. Each did a round of vetting. As noted, Ford minimized the number of US Ford or Mercury dealers receiving Edsel franchises, but such dealers would be permitted as Edsel dealers under some circumstances, and assuming they set up discrete Edsel facilities. A separate round of vetting in these cases ensured that only Ford dealers with good reputations within the company were included. (The situation differed in Canada, where Edsels replaced the Monarch brand, and were sold by Ford dealers.)

Franchisees were not limited to those recommended by local bankers. The Edsel Division received a great deal of unsolicited inquiries on starting a franchise… both from new and used car dealers, and also from business owners unconnected with the auto industry.

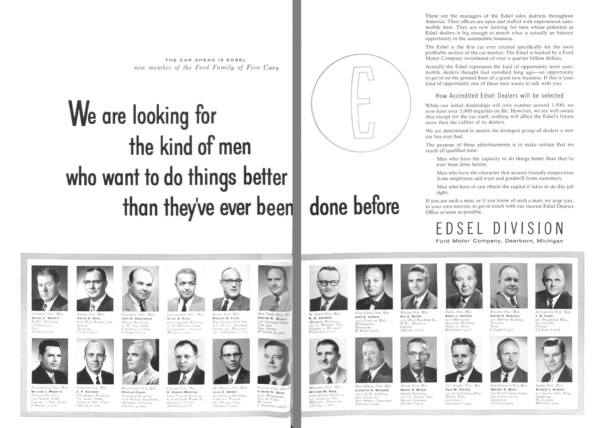

The Division also advertised in business-oriented magazines extolling the benefits taking on an Edsel franchise. Unsolicited applicants were vetted similarly, with Edsel valuing applicants with access to capital and a solid understanding of the business world. Among other things, Edsel promised “elbow room” for new dealers – a boon, since many car dealers at the time complained about an over-population of competitors.

Occasionally, the Edsel Division would become aware of an otherwise solid prospect who was hesitant to commit. For such cases, Doyle stored a handful of Edsel prototypes under lock and key at the five regional offices, and provided a peek at the new cars to fence-straddling prospective dealers. Given the secrecy surrounding Edsel, this was a major enticement. It worked marvelously; most such prospects ended up committing to a franchise.

Of course, opening a car dealership was expensive, generally costing between $100,000 and $200,000 in the late 1950s. To convince seasoned businesspeople to make such an investment on a car with no track record was quite a mission. Accordingly, Doyle came up with a strategy to supplement his Division’s recruitment efforts by getting Edsel news in local newspapers.

This strategy consisted of speaking at business events throughout the United States. For about 8 months starting in the fall of 1956, a handful of Edsel executives travelled the country promoting their upcoming product to local business leaders. Logging hundreds of Jaycees luncheons, Chamber of Commerce banquets and Rotary Club meetings, the Edsel men chased multiple goals.

For one, these meetings resulted in newspaper articles, demonstrating that Ford was making progress with its highly-publicized new car line… and a local byline was more intriguing than a wire-service article from Dearborn. But satisfying the public’s appetite for Edsel news wasn’t the only aim of these presentations. In-person audiences at such events represented a region’s business leadership – including car dealers and finance professionals… that crowd was the real target. These presentations sought to generate excitement from those who might open new dealerships, and to present a positive image for Edsel’s financial health, which would, in turn, benefit nascent dealers seeking loans in the coming months.

While largely the same script repeated in dozens of localities, occasionally the featured speaker would drop a new tidbit of information. For example, during a February 1957 talk in Des Moines, Larry Doyle said “The Edsel will be a distinctive car. It will be a low, wide, roomy car. But it won’t be a sensational departure in style. And we’re not trying to out-fin anybody.” Speculation of the fin-less soon Edsel ran high.

Edsel management signed its first franchise agreement in early April 1957, with more than a thousand following in the five months until the cars’ public debut. To obtain a signed agreement, prospective Edsel dealers needed to prove that they owned or leased a site (with a building, or one under construction) in a location approved by Doyle’s staff, and the franchisee assumed responsibility for equipping the building with fixtures and tools. Recognizing that dealers would remain with little income until they could begin selling Edsels, Doyle urged newly-approved dealerships to start selling used cars immediately, as a way to bring in cashflow. For existing dealerships rebranding to Edsel, he recommended that they continue to operate service departments for their former brands… it would provide income, and (hopefully) a source of future Edsel customers.

Doyle’s organization accredited about 1,100 dealers by Edsel’s September 1957 introduction, remarkably close to his original goal of 1,200. Many more were still in the pipeline. He could have had still more (5,000 applications were submitted), but the Edsel Division favored maintaining their rigorous standards, and accepting only the most qualified applicants. Those accepted dealers came from diverse business backgrounds: nearly half had switched from a “competitive brand” (i.e., Buick, Oldsmobile, Dodge, Studebaker, etc.), while 30% were existing Ford Motor Company dealers that created separate Edsel sales and service operations. Eight percent were used car dealers, 7% former dealers re-entering the auto sales world, and 6% non-automotive business owners.

Carefully framed publicity shots like this concealed the Edsel’s unique details.

Public curiosity about the upcoming Edsel ran high. By the summer of 1957, much more had been written about the Edsel than had actually been divulged. Edsel Division spokesmen revealed bits of information on a regular basis… enough to keep the public interested, though being careful to save the vast majority of details for as close to Introduction Day as possible.

This must have annoyed the Marketing Department – Edsel’s press debut had to compete with a Soviet ICBM for headlines, even in the auto-heavy Detroit newspapers.

Finally, in late August 1957, the Edsel folks allowed press writers to see the car in the flesh. After a two-year wait, this was big news. Magazine and newspaper articles from late August and early September showed the Edsel’s styling, described its features and overall price points, but were generally uncritical. Splashy headlines and effusive prose ended the public’s wanton speculations, though enthusiasm and curiosity to see the car in person were uncurtailed. Rarely has a consumer product attracted so much pre-release attention.

The Edsels themselves arrived at dealers at around the time those newspaper articles published. Dealers (who had to pay for them upon delivery) were ordered to keep them under wraps until Wednesday, September 4, 1957 – the long-awaited Introduction Day.

Introduction Day morning was probably the last time that Edsel’s future looked optimistic. Most dealers were swamped with people looking at their cars – each US dealer telegrammed Dearborn estimating how many people visited their showrooms, and this added up to 2.8 million customers. But by the end of the day, only 6,649 of those customers bought cars.

Despite some witty telegrams, Edsel executives probably knew right then that the project had flopped.

Some Major Reasons for Edsel’s Failure

To better understand how dealers dealt with the intense discouragement that followed, it’s helpful to take a brief look at some of the reasons that led to Edsel’s eventual failure. Among many reasons, a few stand out:

Recession: The summer of 1957 saw worrisome economic signs: Inflation increased, interest rates rose – and Americans began to curtail their enthusiastic consumer spending that characterized the preceding five years. Eventually, this would be known as the 1958 recession, and its timing couldn’t have been worse for Edsel.

The recession hit quickly, and new car sales suffered, particularly the middle of the market, since the recession hit the middle class hardest. When asked about the disquieting economic trend, Edsel General Manager Richard Krafve was hardly reassuring, saying “I don’t think that anyone is smart enough to evaluate what is happening this year in the medium-priced field.” In fact, new car demand quickly slumped, causing excess inventory at many dealers, who responded by discounting their prices. This was awful timing for Edsel dealers, who had assumed they’d sell cars at, or above, the asking price. Furthermore, every Edsel sale must, by nature, have been a “conquest sale” where the customer was won over from a competitor. That’s the toughest type of sale, particularly in recessionary times when people are less likely to take chances.

Though few foresaw the upcoming change, the recession did have a significant impact on carmakers… for customers developed a sudden interest in compact, value-oriented cars, turning their backs on “older” 1950s designs, like Edsel. Between September and October of 1957, just when Edsel sales launched, America’s fastest-growing nameplate was… lowly Rambler, whose sales increased a staggering 131%.

Pricing: Edsel’s reason for existence was to capitalize on the mid-price market, which was hit badly by the recession. But Edsel faced further disadvantages regarding price. Ford naturally assumed intense interest at introduction and a likelihood of Edsel’s higher price range models being particularly popular. Additionally, dealers assumed that a year’s worth of hype would lead customers to buy cars with little haggling.

Neither of these turned out to be true – customers wanted bargains, and Edsel’s early-September launch unfortunately coincided with close-out specials at other dealers offloading their slow-selling ’57 models. Consequently, Edsel quickly developed a reputation for being overpriced, which was a death knell in a price-sensitive, recession-induced market.

Couldn’t Live Up to Its Own Buzz: The Edsel project was hyped for years – making this one of the most newsworthy new car introductions of all time. But consumers ultimately viewed Edsels as little more than gussied-up Fords. Other than the ’58 model’s novel pushbutton transmission (with buttons on the steering wheel hub), the car introduced no innovations, and the overall styling looked like an accessorized Ford product. The public was far from impressed.

Internal Bureaucracy: Many in Ford Motor Company’s upper echelons viewed Edsel as an unwanted stepchild. This made it difficult for the Edsel Division to recruit existing Ford employees, challenged the development and manufacturing processes, and ultimately hastened the brand’s demise.

Of all Ford employees, it was Vice President Robert McNamara who emerged as the Edsel’s most formidable nemesis. He was never enthusiastic about creating a new mid-price brand, and as soon as Edsel stumbled out of the gate, McNamara put his full weight and oppressive personality behind an effort to eliminate the brand as soon as possible. McNamara got his way, and anyone who offered a means to save Edsel found himself browbeaten into submission.

Quality: Edsels developed a reputation for poor workmanship. Cars were delivered to dealers with improperly fitted panels, malfunctioning electrical accessories, and even disassembled pieces for the dealer to finish the job. The acronym “Every Day Something Else Leaks” became a fitting moniker for a car that was obviously assembled with indifference.

Much of this had to do with the manufacturing process whereby Edsels were produced alongside Fords or Mercurys, which resulted in production line workers and management resenting Edsel’s intrusion and the accompanying complication of their assembly lines. However, the real fault for these embarrassing defects upon delivery lay with Ford upper management, who was aware of the problem and did nothing to rectify it. That brings us to the Edsel’s most well-remembered problem…

Styling: As mentioned earlier, Edsel’s stylists aimed for a car with distinguishing features when viewed from every angle. Given the heady 1950s, these ended up being rather exaggerated styling features.

Most notably, of course, was The Grille. Obviously planned as the car’s Most Distinguishing Feature, the vertical, oval grille was intended as a counterpoint to the prevailing 1950s theme of horizontal car designs. Apparently, some people complained that all those new cars looked alike, so lead designer Roy Brown, Jr. incorporated a vertical grille to stand out from the crowd. Said Brown just before the Edsel’s release: “It is crisp and fresh-looking; that grille could become a classic.” The public, however, disagreed.

The horse-collar-shaped grille attracted quite a bit of ridicule. Within a month of Edsel’s introduction, comedian Danny Thomas quipped that it looked like “an Oldsmobile Sucking a Lemon.” That saying, and many others, stuck. Edsel was branded as ugly, and it was doomed.

Edsels had other distinctive styling features. Doyle’s subtly-dropped assertion that Edsel wasn’t out-finning anyone really meant that the Edsel’s fins were horizontal, gullwing style.

And on the car’s sides, concave scallops, intended to convey a sense of motion, extended for nearly half the car’s length, accentuated by available two-tone paint.

But other than these main features, Edsels had a long, low look corresponding to the era’s prevailing trends, not terribly dissimilar to contemporary Mercurys. In other words, many prospective customers viewed the much-anticipated Edsel as just a typical car with an odd grille. While styling alone didn’t doom Edsel, it certainly contributed to the public’s nonacceptance of this newcomer, and is the attribute of these cars that is most remembered today.

All in all, Ford simply misjudged the market – led astray by a combination of a suddenly souring economy, overly optimistic thinking, poor quality, and flawed consumer research. Rarely has one car’s introduction been met with such a combination of poor luck and poor planning.

With that introduction, we can take a closer look at a few Edsel dealers, and their unique perspective that’s often overlooked when telling the well-known Edsel story.

Please select Page 2 to continue

The Edsel!. 64 years later its still remembered as a text book example on how NOT to market a new car. 7 years and a bit later Ford launched the Mustang. Now that was how it should be done.

As for sales… I read that owners were asked ” Which tv game show did you win on?”.

Thank you for a most interesting history of the Edsel. Being European, I have heard of Edsel and its failure(s) but never much in detail. Amazing that so much effort and money was spend in only a few years. To know that it only existed for just over two years, with unique dealerships, is just mind blowing. They really got it wrong.

The car was an anti climax after all the hype. A new kind of car but it wasnt just another overpriced barge that was launched at start of the import craze for smaller ,cheaper cars. Interesting that two dealers ,above, sold imports along side or after ditching the Edsel brand… .

What could have happened if the brand was launched in 1955 I wonder…

If you were an Edsel dealer, sandbagged by the failure of the car, going to one of the import marques was about your only alternative, assuming you wanted to stay in the new car business. And having bought, rented, or built a new showroom, you certainly weren’t that keen on falling back into the used car business only.

Plus, 1959 was the big year for the first import invasion. Lots of small (in America) marques were selling very well, and the manufacturer’s expectations of what it took to become a franchised dealer wasn’t anything near what Detroit expected. Keep in mind that Volkswagen was unique in having very high, relatively expensive, expectations to take on their brand. A lot of the competing marques were pretty much “buy x number of cars and y amount of parts” and you’re a dealer.

. . . “buy x number of cars and y amount of parts” and you’re a dealer.

IIRC you’ve posted about a shoestring Renault dealer in Erie, PA.

Yep, the prime example of this in my memory. It was a neat place if you were into rusted out Lancias.

Very interesting and well written history of this ill fated brand! Thanks……. 🙂

To show what a “smart” car buyer I was going to be, my very first car model was a ’58 Edsel AMT 3-in-1 kustom kar kit!! Oopz…..and like real Edsels it had a problem; all 4 wheels and tires had been ripped off from the kit. I did get it at a slight di$count tho, only $1.00 instead of the “list” price of $1.25. Purchased in the Fall of 1957 in downtown Madison, WI at Wolff Kubly and Hersig dept. store…………tho$e were the days! The following week I bought a ’58 Ford Fairlane 500 which I still have. Unlike Edsel or my Edsel model, the Ford has survived. DFO

I have one of the dealer promotional models of the ’58 Edsel (that model is turquoise and white) that, as a child, I somewhat hacked up into a NASCAR stock car (I was kinda into the sport back then due to Jennerstown Speedway, the local half mile dirt oval). I never did attempt to put it back to original, as my modifications were pretty much decals, putting a roll bar into the interior, and removing the front chrome work.

It definitely looks odd amongst my collection of ’53-65 Chevrolet dealer promotional models.

For at least two decades, every time I’ve come across an article about Edsel, I thought to myself, “Aw, c’mon, man! Hasn’t this horse been beaten to death already?”

And along comes Eric703 with not only a perspective I’d never seen written about before, but one I’d never even considered.

Well done, Eric!

Thanks! It’s tough to even contemplate writing about well-known cars like the Edsel since there’s been countless books and articles written before. But when I started looking into the dealer aspect, I was surprised at how little information has been pieced together about this. Glad you enjoyed it.

Wow, what a fabulous history of an aspect I have never seen treated in much depth. I found an Edsel site that has a listing of Edsel dealers, and the two shown for Indianapolis are not ones I have ever heard of. I have understood that one of the reasons for the 1959 Studebaker Lark’s success was that quite a few (desperate) Edsel dealers took on a Studebaker franchise for 1959 in addition to the Edsel.

I saw the chart, and that was amazing in the change in body styles from 1958 to 59 – those changes mark a hard change from an aspirational car to a practical car for thrifty folks. I had not really thought about that before, but it is true – most of the (few) 58 Edsels I have seen are hardtops while most of the (even fewer) 59s have been sedans.

It is a good thing for Ford that this happened when it did – I can only imagine how much more tempted dealers would be to sue for fraud or misrepresentation today than back then. Even then I would imagine that there were some lawsuits against Ford from dealers, that would be interesting to look up.

Thanks JP!

The Edsel Dealer Locator (http://edsel.net/dealer_locator.html) website is fun to look at, and see where all the various dealerships were located. I didn’t realize that there were a significant number of Edsel dealers that added Studebaker — I wonder how many of those had actually been Studebaker dealers beforehand as well?

I did come across a number of references to lawsuits filed by Edsel dealerships against Ford Motor Co., often for misrepresentation (of the price, of Ford’s commitment to their franchisees, regarding the quality of the vehicles, etc.). There were also some lawsuits about Ford coercing exclusive Edsel dealers into giving up their franchises, and others about coercing other Ford and Mercury dealers into accepting an Edsel franchise in 1959. While I didn’t spend too much time on this topic, those lawsuits that I did track down ended up being dismissed. I think some of those suits dragged into the 1970s — I’m sure that was a real popular assignment for Ford’s legal staff.

Regarding Edsel dealers and Studebaker. My hometown (Joliet, Illinois) Studebaker dealer took on Edsel, keeping Studebaker in the same location initially. Later, they built another location for Edsel, and which became a Lincoln-Mercury-Edsel dealer. He kept Studebaker in the original location.

I can only imagine how much more tempted dealers would be to sue for fraud or misrepresentation today than back then

So what exactly was the fraud and misrepresentation that Ford committed? For not being able to foresee a sharp recession and the public’s sudden turn away from big flashy cars to compacts and imports? That’s essentially what killed Edsel.

That reflects a lack of prescience on Ford’s part, but I don’t see it as fraud or misrepresentation. But then I’m not an attorney. 🙂

I didn’t research a whole lot into this topic, but the lawsuits I read about claimed that Ford misrepresented the car’s price & market positioning, and there were lawsuits about the poor quality as well, especially dealers that were consistently shipped cars that required extra assembly. I assume this last point worked its way into the lawsuits because it was probably closer to actual misrepresentation in a legal sense than the other points.

In the cases I read about, the dealers’ attorneys cited Ford’s promotional materials, personal conversations/promises to their clients, etc. as the basis for this misrepresentation. But the courts noted that Ford did not violate its actual contract — so most of these cases were dismissed. I say “most” because I wouldn’t be surprised if a few succeeded somewhere… if so, I’d like to hear about it.

Considering the amount of money they lost, I doubt blame the dealers for trying this angle.

My question was for JP, as he’s the one who intimated that there was fraud and misrepresentation. The issues you cited don’t sound like legitima fraud and misrepresentation. They sound like unhappy dealers whose attorneys thought they could find an angle to sue on.

Crappy quality was endemic at this time. Ask all the 1957 Chrysler Corp. dealers. And Ford dealers in 1957.

As to the car’s positioning and pricing, it seems that from everything I’ve ever read and seen, its positioning was quite obviously between Ford and Mercury. As to the pricing, well, every car manufacturer reserves the right to set the final pricing. And certainly the Edsel’s pricing was right about where its market positioning was.

It all sounds like the expected grumbling of folks who took a risk (along with Ford) on a product that was the wrong thing at the wrong time. It’s not like anyone forced these dealers to take on Edsel. They took a flyer on what they thought was going to make them some coin. That’s the allure and nature of a new business venture. Not all new business ventures pan out, obviously. There was no way for either Ford or the Edsel dealers to come out whole on this one.

I dealt with some of this above (or below, actually), and you are mostly right, and I agree that claims for actual fraud and actual misrepresentation would not have gone far – in a big picture.

I have no doubt that there were arguments that could be made with a straight face back then that Ford overhyped the likelihood of success and set up the Division’s sales system in a way that put far more risk onto these folks with no background in the auto business than might have been expected. That sort of thing might have a lot more success today than it could have in 1960, but the contracts were surely written in a way that protected Ford to the detriment of the guy buying the franchise, so some kind of tort/negligence/fraud argument would probably have been their best (though not strong) shot.

I was rushing to get out the door and used fraud and misrepresentation generically, but there were undoubtedly able lawyers who could craft an argument to explain why their clients felt cheated.

I did see one case (which the dealer finally lost in 1966) where an LM dealer was approached in mid 1959 with a take it or leave it proposition – either take an Edsel franchise or forfeit your LM franchise. The dealer did not want Edsel and elected to Forfeit. However, he later claimed that the killing of Edsel was well along in planning when the proposal was made, and not disclosed.

I recall seeing a reference to that case; I couldn’t remember what the outcome was.

I believe there were also lawsuits regarding how Ford compensated departing Edsel dealers for unsold inventory. In some cases, Ford purchased back unsold cars, but in other cases, they did not, claiming that dealers where relinquishing their franchises willingly and therefore the obligation to sell the cars was theirs. I don’t know how those cases worked out, but it seemed like a messy situation.

I was rushing to get out the door when I wrote that comment and used fraud and misrepresentation as the general direction for suits. There are always lawsuits when someone loses a ton of money and I have no doubt there were plenty back then (most not successful). There would have been all kinds of grounds someone could try, mostly state law back then. And, of course, just because you can file the lawsuit doesn’t mean it has merit.

After the initial batch of dealership sign ups, I imagine the issues would have changed. I located one case out of Illinois where a former Lincoln-Mercury dealer sued Ford, alleging that Ford had presented a take-it-or-leave-it proposal to either accept an Edsel franchise (which the dealer did not want) or forfeit the L-M franchise. The dealer forfeited, but later learned that in mid 1959 (when this all happened) Ford was already reasonably aware that Edsel would be cancelled. The dealer eventually lost (in 1966) as most of them did, but I am sure there were plenty of creative arguments.

My point was that while there were some suits in the very early 60s after these franchisees lost their shirts, there would undoubtedly be a lot more of them today.

A couple of thoughts from back in that era:

Around the age of 12 (1962-63) I heard my first ‘dirty’ joke, which sticks with me to this day:

“What is the definition of a loser? A pregnant prostitute driving an Edsel with a Nixon bumper sticker?” (Definitely late 62 or sometime in 63, as this came out after Nixon had lost the race for Governor of California, and was pretty much considered politically disgraced and over.) Such was Edsel’s legacy.

As to multi-car dealerships: While Ford was willing to go with the idea and Chrysler always had them, at least as far as Plymouth was concerned, this was a huge rarity within the General Motors organization. My father was the manager of Hallman’s Chevrolet in Johnstown, PA which was somewhat unique in the business: A multi-store chain. And the way it came about was an indication of what you had to do to get around GM’s expectations.

The Hallman chain was based out of Hallman’s Central Chevrolet in Rochester, NY, owned by the father, Maynard Hallman. He had (if my memory is still good) six sons, each of which ‘owned’ a Chevrolet dealership, pretty much all of them in upstate New York. These were all clustered in an organization based out of Rochester, then in the early 1950’s (can’t remember the exact years, I was probably too young to notice), they bought out the Motor Sales Corporation in Johnstown. Dad was the new car manager there at the time, and was promoted to General Manager, which he held until the end of the 1965 model year, and was then let go. Never found out why, but I can guess, knowing my father’s attitude and ego at the time.

Another outside manager was brought in, who turned out to be a disaster. By the 1968 model year the dealership had been sold off to one Rudy Haupt, secretary/treasurer of the Hallman chain (and, from my understanding, the guy who was the major push behind replacing my father), becoming Rudy Haupt Chevrolet.

Meanwhile, the Hallman organization kept rolling. Having given up Johnstown, by the 1970’s they’d bought the Chevrolet dealership in Erie, PA (one of the sons ran it) which still exists today at 19th and State St. Meanwhile, my father had dropped out of the automobile business completely, other than helping (his old contacts in the Chevrolet Pittsburgh Zone were invaluable) the formation of a third Chevrolet dealership in the 20 mile radius Johnstown area, Watkins Chevrolet. They, plus the already existent Marhefka Chevrolet in Windber (which was always a pain in the butt to my father) definitely ensured that Rudy Haupt Chevrolet never had the pre-eminence that Hallman’s Chevrolet had had.

In the Johnstown area, we only had one doubled-up GM dealership: The Pontiac Cadillac franchise. The town’s Oldsmobile dealer also took on Renault, later adding Datsun/Nissan. Johnstown was a small/medium sized city at best (50,000 population at it’s height, with another 50,000 in the outlying suburbs), thus the doubling-up.

A fabulous article that thoroughly explains what happened at Edsel and the tribulations in getting them shoved out the showroom door. Giving away ponies to sell an Edsel? Wow.

Out of curiosity, I did try to look up the addresses shown in the ads for the Jefferson City Edsel dealership. The Datsun dealer building appears to be gone, located (via street address) between a Jiffy Lube and a vendor supplying replacement auto glass. Nothing turned up for the original Edsel building, which could have happened due to the construction of the US 50/54/63 interchange in the 1960s.

Of the Edsel staff, two names are familiar. Elmer Haslag has a surname common for this area. Bob Steinmetz had/has an auto repair facility roughly between the Edsel and Datsun dealer locations.

https://www.steinmetzautomotive.com

I’ve tried to pinpoint the exact location of the Jeff City Edsel dealer, but to no avail. I’m guessing at some point, the property was subdivided or merged with others, or the addressing changed, or both.

The Datsun dealer’s location I know well, since it’s next to Foster’s Transmission, a shop that our family uses.

Looks like after the Edsel dealer folded, Bob Steinmetz joined with a business partner to start their own garage (Bob & Ernie’s Auto Repair), and then a decade later, he moved to his own location, where Steinmetz Automotive is still located. I bet that the Bob who currently runs the shop is the original Bob’s son.

Excellent article. I wonder if the no dualling policy contributed to the marketing failure. If existing Ford dealers had been part of the early planning process, with a promise of adding the new brand, they could have told Dearborn what buyers really wanted. They would have known why buyers moved up easily from Chevy to Pontiac but not from Ford to Mercury.

I suspect the Chevy to Pontiac motive was 6 to 8. Ford was already 8, so there was no reason to move up to a slightly bigger 8.

GF had always bought Hudsons. Kept his last one so long as possible. Hudson dealer became an Edsel dealer and he got a turquoise 1958 Citation w/ every option.

Not a good car, front wheel came off while driving and he said it passed him on the left.

Switched to Chryslers, his last a 1965 New Yorker which was the best car he ever owned

Fantastic, well written article!

The Edsel horse has been beaten to death (even around here, and we curbivores by and large love Edsels), but this is a great new take with a bunch of new information I had not seen before.

Fantastic read, Eric703!

Dear Eric, I agree with the statement TERRIFIC ARTICLE! Thanks for the information. When the Edsel was introduced, I was fifteen years of age. The years following up to its introduction were indeed filled with promotional spots in newspapers to get the buying public interested. What impressed me and my friends was that the “oval grille” looked like a vulva. This is not a nice appearance. The fact that it looked like a gussied up Ford did not help. The recession certainly was a problem along with the quality. The quality control is, of course, the fault of Ford. Ford would have done better to change the image of the extant “Big M” (Mercury as it was advertised) to keep those Ford customers stepping up to a pricier car.

Fantastic article! While in college in the early 80’s, my senior year marketing class term paper was on the development and marketing of the Edsel – though I never looked at from the dealer’s point of view. Thanks so much for writing this, I truly enjoyed it!

That picture, on opening day, of the man staring at the “horse collar” is intriguing. What was he thinking? We would probably have a 80% chance of the correct answer. I vaguely remember staring at one, in 1958, at the age of four, at our home outside of Cleveland, Ohio. Of course, over time, I put the memory with the car. I recently saw a movie where a ’58 convertible was driven, and to me it seemed to have a presence, and a sense of security in that it would reliably get away from any threat to it’s occupants….at least in this movie.

Funny that you mention Cleveland, because Cleveland was the location of an amusing Edsel story.

About a week before the Edsel’s September 1957 Introduction Day, a Cleveland used car dealer (Helbig Auto Sales), shocked everyone by putting an Edsel convertible on display in front of his lot.

It got lots of attention, and within days, word got to Ford Motor Co. No one knew where the car came from. Turns out, the attention-seeking Mr. Helbig had one of his associates travel through New York State in late August (just after Edsels were delivered to dealers, but before they could display them), offering dealers a generous cash price for a new Edsel convertible – on the condition that he take delivery immediately.

After not finding luck at a dozen dealers, he found a willing seller in Manhattan, where Charles Kreisler (who gave up an Olds franchise months earlier to sell Edsels) sold the car to Mr. Helbig’s associate. Presumably, the Clevelander promised to keep it under wraps until Sept. 4. He transported the convertible to Cleveland… and promptly displayed it on his used car lot, 5 days before E-Day.

Ford officials were furious, and immediately tried to figure out where the car came from. Kreisler, knowing he’d goofed, attempted to buy it back, but Helbig refused to sell. Kreisler even even sent his own sister as a mystery buyer (with lots of cash) to get it back, but she couldn’t keep up the charade, and Helbig figured out she was related to Kreisler, so he wouldn’t sell.

About a week or so later, Ford officials did trace the car back to Kreisler. Many Ford execs wanted to strip away his franchise, but instead the company punished Mr. Kreisler by demanding that he telegram an apology to all 1,200 US Edsel dealers… which he did.

Kreisler had the last laugh, though… he was the first Edsel dealer to abandon the brand, switching to Rambler in November 1957.

In 1958 I would have chosen a Peugeot or Borgward over an Edsel, no contest.

Thank you for this excellent article. I thoroughly enjoyed it, particularly the stories of those dealers. History isn’t just the big, bold events; it’s also the many smaller events and minor participants that create the tapestry and brings the bigger picture to life.

Thanks, Paul! I agree that the minor participants in historical events are often more compelling to read about than the more notorious people. I’m glad I could piece this all together in a way that folks enjoyed reading it.

Just when I thought that I’d heard most of the Edsel story, you come up with a unique take and most informative article. Well done!

If Ford had read the tea leaves better, and had some genuine guts and daring (like AMC did), the 1958 Edsel would have looked like the image below. Image what a colossal hit that would have been in 1958!

History would have been quite different. Rambler’s huge rise would have been significantly dented, as well as the Lark’s.

Instead they chased a market segment that was already over-saturated. A classic Detroit move: (seemingly) safe, lacking imagination and being out of touch with the latest trends on the coasts: import sales were rising very strongly in 1955-1956 at the time they committed to the E car.

They deserved the black eye they got.

You are correct, of course – the Falcon in 1958 would have been huge. But then the Falcon and the others only really came about because of reactions to market conditions after 1955.

Which raises an interesting question – how many auto manufacturers ever introduced a really innovative car when what they were already doing was working really, really well? The Nash Rambler might be one, but most really consequential innovations seem to come when the company’s back is against the wall.

The Mustang. Not technically innovative (obviously) but absolutely brilliant (and innovative) in terms of what it was: a sporty compact with a totally new set of proportions for a mainstream American car.

Ford could have easily done what Chrysler did with the Barracuda, keeping the Falcon’s proportions with sporty affectations. It was a bold gamble that succeeded beyond their expectations.

I would also say that the downsized GM B-C Bodies of 1977 fall in that category. GM committed to that program before the energy crisis of late 1973 set in; they read the tea leaves, and took a pretty big risk going as far as they did.

But yes, the number of examples are sparse. Which explains a lot about the fortunes of the US car industry.

Maybe not in the USA, but in Europe there was a string of innovative cars built by manufacturers in a strong financial position:

Mini/1100

Citroen DS

Renault 4/16

Nearly every FIAT from the 600 to 128

Jag E type, XJ6

There were also many failures such as the Borgward Lloyd, Hillman Imp, VW 4 series and the NSU ro 80.

A great article, best of the year?

The irony here is that the 1960 Comet was originally intended to be an Edsel. The Comet’s taillights mimic the taillights of the 1960 Edsel, and even carry the Edsel parts code.

The decision to abandon the Edsel meant that the car was simply sold as the Comet (it wasn’t badged as a Mercury until the 1962 model year). No doubt Ford also realized that saddling the new car with the Edsel nameplate would seriously hinder its chances for success. The 1960 Comet was a mid-year introduction, and, even with an abbreviated model year, still managed to sell as many cars in its debut year as the Edsel did from 1958 through 1960.

Interesting and well done take on the Edsel deal.

At the end of the day, I think the front end of the thing could not be ignored or overlooked. Love it or hate it, but most people simply wanted nothing to do with something that novel looking and simply unattractive. The initial reaction to the stylists’ unveiling in 1955 told one everything he needed to know, but no one was paying attention.

The ‘yes” or “no” is decided in the first ten seconds. Edsel, “no”. Mustang, “yes”. It is as simple as that, and all of Ford’s good work on getting the Edsel dealerships up and squared away was wasted.

It’s interesting to read Edsel press coverage from late 1957, and see just how quickly things turned south regarding public perception (largely regarding the styling).

Early press reports – when Edsels were first previewed to the press – were largely positive. I’ve read nothing from those weeks that was critical of the styling. Quite possibly the news writers were afraid to be critical, but the positivity is odd to read in retrospect.

By late September, 1957, Edsels were often referred to as “slow-selling,” but it seemed that the “Oldsmobile with a lemon in its mouth” comment was pivotal. As far as I can tell, that line was first used by comedian Danny Thomas during stand-up routines in early October, 1957. The joke was included in a Time Magazine article in early November (though not attributed to anyone in particular), and from there became the ’50s version of Viral. Other jokes followed, and Edsel could never recover from the burden of being called Ugly.

To add on to what others have already said, what a great new perspective on what most would think is a long-beaten dead horse.

Thanks for a fresh perspective on one of the best-known failures in American business history.

I too found the stories of the individual dealers quite interesting. I am amazed at the come-and-go (fly-by-nght?) nature of the auto dealership business back then. It added yet another element of risk to an already dicey proposition of buying a new, as yet unproven car, whether it was an Edsel, an import or any other brand.

And, back then, it seems that warranties were, at best a very short-term proposition as well, so it’s entirely possible that a customer who bought an Edsel in say, September or October 1957, would have been unable to return to the selling dealership (and the only Edsel outlet for miles around) for one of the umpteenth needed repairs as early as Spring 1958, as in Jefferson City, MO.

It’s interesting to see just how much churn there was in car dealerships back in the 1950s. From what I can tell, it wasn’t uncommon at all for a dealership to last just a year or two, and many dealers took over the physical facilities of other dealers, in transactions that often included sales and/or service personnel as well.

I know the Mark Edsel location in Arlington, VA very well. In mid 1955, Mr. Harry Dubois [pronounced “dew-boys”] visited the Packard Motor Company. He was attracted to the car company after attending a Studebaker-Packard conference intended to find more dealerships. Mr. Dubois bought a Packard dealership franchise, but was unable to buy the Studebaker franchise because of the nearby Arlington Service Center, a long-time [and very successful] Studebaker dealer. Harry bought the location featured here that became Mark Edsel.

So Dubois Packard opened to great fanfare in the early spring of 1956. Less than a year later, the Detroit-made Packard and Clipper lines stopped production forever. Off the top of my head I can’t remember the exact number of Packard and Clipper cars sold by Dubois, but the number was around 150 to 250 cars total.

As the new 1957 Packard line was based on the 1957 Studebaker President sedan and station Wagon, to sell the new 1957 line would have required an entirely new parts inventory. That huge expense, plus with Dubois Packard situated very near the Studebaker dealership, the answer was simple. Harry Dubois closed his Packard dealership and walked away. I was able to talk by phone with Harry Dubois several times prior to his death in the late 1970s, hence my knowledge of the subject.

Today the Dubois name lives on in a very rare Packard model that officially never existed, but as I’m working on a CC story about these unique and interesting cars, that info will have to wait & become a new CC story in the near future.

Bill, thanks for that history. I wasn’t quite able to place what happened to DuBois Studebaker-Packard, since they seemed to leave quickly.

Do you happen to know what the relationship was between Dubois and the building owner, B.F. Burner? Burner purchased the building in 1955 from Kirby Dodge, but I wasn’t sure if he had an operational relationship with the Dubois company, or if he was just their landlord? Burner was involved in the Edsel dealership, and he’s the one who started the Imported Car Center after Eisner left for Maryland.

I do know that Eisner kept the Dubois mechanics, and I believe their Service Manager as well, so the transition between the two dealers must have occurred pretty quickly.

I wasn’t able to uncover a picture of this building while it was still an Edsel dealership, but I did find this (unfortunately poor-quality) photo from its Dubois Packard days:

Harry was the point man for the dealership, but if I remember correctly, he was in business with his brother. I always assumed they owned the property, but it seems they simply leased it.

Thank you for the photo, I can now include that in the Packardinfo.com dealership records. I wrote the report for Dubois, but I had no photo until now. Again, thanks.

This is one of the finest and most interesting pieces of automotive history that I’ve read in a long time.

The pony saga had me in stitches.

Thanks, Eric703!

You’re very welcome — glad you enjoyed it!

I’m surprised there aren’t more pictures out there of the pony saga, since it was such an oddball promotion, but this is the most well-known one… from Life Magazine:

Here’s a commercial for the Edsel pony promotion, featuring Ward Bond from the TV series Wagon Train:

youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=rZ4S24PruN8

The Washington Post had an article years back describing it (and the whole Edsel debacle) too: “The story of the Edsel is a farce that might make a good Mel Brooks movie, a tale of human folly, corporate arrogance and vast piles of horse excrement, much of it metaphorical but some of it, alas, all too pungently real.” Later, after describing several ineffective marketing promos that had fallen flat, they continued:

“But the Edsel folks did not give up. No way. After months of sluggish sales, the crack PR team gathered to brainstorm ideas for selling Edsels. They were battered and weary and devoid of ideas until an adman named Walter “Tommy” Thomas blurted out a suggestion.”

“Let’s give away a [bleeping] pony,” he said.

“Much to Thomas’s amazement, his idea was not only accepted, it was expanded. The geniuses at Edsel decided to advertise a promotion in which every Edsel dealer would give away a pony. It worked like this: If you agreed to test-drive an Edsel, your name would be entered into a lottery at the dealership, with the winner getting a pony. Ford bought 1,000 ponies and shipped them to Edsel dealers, who displayed them outside their showrooms. Many parents, egged on by their pony-loving children, traipsed in to take a test drive. Unfortunately, many of the lucky winners declined the ponies, opting instead for the alternative — $200 in cash — and soon dealers were shipping the beasts back to Detroit.”

“Now the Edsel folks were not only stuck with a lot of cars they couldn’t sell, they were also stuck with a lot of ponies they couldn’t give away. The cars were easy enough to store, but the ponies required food. And after they ate the food, they digested the food. And then . . . another fine mess for Edsel.”

Full article here: https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/09/03/AR2007090301419.html

Any figures on the take rate for ponies rather than the $200?

I grew up in a rural area, but I never had the desire for a pony. If I’d wanted my parents to test-drive an Edsel just to enter the pony raffle, I’m sure they would have said no. They would have said that since they weren’t serious prospective Edsel owners, it wouldn’t have been fair to take up the salesman’s time, and they would have been right.

In the suburbs where I grew up, I didn’t know ANYONE who had a pony, and few if any who would want to own one (although some wouldn’t mind seeing one elsewhere, for one day anyway).

What a weird promo. I bought my 2007 VW Rabbit when they had a promotion where if you bought a new Volkswagen, you got a free VW-customized electric guitar (knobs have VW logos, neck strap is a seatbelt, etc.) which was color-matched to the car you bought. The sales manager at the dealership hated that promo though – “we sell cars, not guitars”. I thought it was cool though; still have it today and its presence in my living room has started about 20 conversations about VWs over the years. But why guitars of all things? VW wanted to promote the new-for-2007 auxiliary input that allowed you to feed audio from iPod or phone directly into the car stereo. The guitar had a unique feature of a small built-in amplifier (complete with switchable distortion) so you could plug the guitar into the car and use the car stereo as a guitar amp. Pretty cool IMO. Also, if you combine the guitar’s built-in amp and distortion with an actual guitar amp’s distortion, you can get some wild sounds.

I’d love to know. Like LA673 says above, how many people would actually want a pony, even in the 1950s.

Even though the pony promotion was billed as a contest (where kids submit a name for the pony, and then a winning name is chosen), I wouldn’t be surprised if the dealerships gave more than a bit of preference to families who indicated they could actually take the animal. That way, the pony would get out of their showroom quicker, and they wouldn’t have to worry about shipping it back to Ford. Just a guess.

The more you think about this whole thing, the more there is to chew on. I’d think it would have been more practical to have the pony shipped directly from the breeder to the winner after the winner had been chosen. But they probably thought people would be more motivated to take a test drive and enter the contest if the pony were actually at the dealership. And of course, to submit a name for the pony, you need to know its gender.

I suppose that shipping a single equine long distance is doable if you know how.

Ironic that the pony promotion worked out so badly, but a few years later Ford created the ponycar category with the Mustang.

There was some kind of arragement analogous to the Allowance Certificates for the few people who bought ’61 DeSotos. IIRC it was a $300 credit on a future purchase of a ChryCo car. I don’t know if it had an expiration date.

Imagine the corresponding promotion for the Kaiser Golden Dragon!

I wonder what sort of mechanical innovations Edsel might have offered that would have made it a standout in the mid-price field. Nothing comes to mind perhaps some curbivores have some ideas. Thanks

The cars in that segment didn’t really sell on technical features; they sold on the existing brand image that had been built up and cultivated over decades. Edsel had zero…and as soon as folks saw that no one was rushing to buy them, its brand image went from zero to a large negative number.

Brand image has always been a key driver of automobile sales. Nobody wants to be associated with a loser brand.

I suppose if they had used the Fish 250 mpg carburetor…

How about an AM-FM radio?

My thought: “What can I do to make this car look better?”

Using MS Paint (I don’t have Photoshop) to cut and paste and bodge. It turned out okay…but what to do with that hood? Aha! Make the front a vacuum operated air induction scoop where the cone moves back and forth like the SR-71 blackbird! That’s the sort of gimmick that would have sold the car! Plus it’s recognizable from a distance, so it would have met the ‘easily distinguished’ goal. The right side has hidden headlights too

Caught an error in the above pic and fixed it

Interesting that three days after the launch, yours truly was launched. Thankfully Dad wasn’t much of a FoMoCo guy otherwise I might have been named Edsel. Instead of Francis…from a talking mule to a mule collar…whadda woild…

I learned a lot about the Edsel saga that I never knew! Focusing on the dealers and promotional efforts–great angle!

Two things stand out:

1) How many “Larry Doyle’s” are out there? People who go to work, spend their whole working day–years of their health and time–doing skilled, high-quality, conscientious labor on some project that in the end turned out to be worthless, unnecessary, a waste, and a money-loser–mainly due to corporate politics and stupidity over which he had no control?

2) The pony thing, LOL!! Can you picture a bunch of bourbon-drinking, chain-smoking hotshot car salesmen TAKING CARE OF A PONY??? “How much hay to I feed this thing?” “Hey, George–you didn’t sell any Edsels today so you clean up the horses**t!” It’s a wonder none of the animals died! (Or did they?)

Thanks! I definitely felt sympathy for what Doyle went through. After all, it’s a situation that many folks find themselves in: Getting picked for a task you don’t really want to do, and even though you do your best, no one notices or cares, due to circumstances beyond your control.

Doyle abruptly left Ford Motor Co. in Feb. 1958 – first taking an unspecified leave of absence, and then two months later simply resigning. Before his leave of absence, he was traveling the country giving pep talks to dealers – undoubtedly he knew the ship was sinking at that point. I can only imagine his exasperation.

From what I can tell, Doyle worked as an independent auto-industry consultant for about a decade after his departure from Ford. He lived into his 90s… by the time he was older, Edsels (classics, by then) finally became popular, and in retirement he frequented Edsel club meetings, where he was always a welcome speaker.

Doyle retired.

I’m not sure where you did all this research at but a lot of the finer details are completely amiss.

I responded at length at the end of comments but I notice you’ve not responded at all…

I’m not sure if your contention is about Doyle taking a leave of absence, or my term in the comment above that he resigned.

Regarding the leave of absence, I came across that in various sources. The one that’s in my notes is a Detroit Free Press article from 2/18/58 that stated Doyle took “a leave of absence for personal reasons.” Later articles indicate that he retired on April 30. In the above comment, I used the term “resigned” as synonymous with “retired.”

I read your lengthy comment below. Ordinarily, I’m very happy to share sources and discuss details with folks who are interested, but I have little interest in responding to comments that are unduly accusatory or argumentative.

I’m pointing out he didn’t “resign” per say- he retired and there is a difference. What’s with you and the use of terminology that makes things sound worse than they were?

Argumentative? I pointed out correct facts that are errors in your article—- I’m not interested in your sources for erroneous info- I can back up everything I put forth. It would seem to me you’d be interested in accuracy and correct facts since you delved into this as deeply as you already did… 🤷🏻♂️

If my correcting you has offended you that’s fine— I would rather have correct information posted for the record than people reading the entirety of your article thinking it’s correct— because it’s so far from accurate it honestly deserves a rewrite…

Regarding the ponies, in his book “The Edsel Affair,” C. Gayle Warnock devotes a few pages to the Pony Thing.

Among other oddities about that how ordeal was that Ford discovered it’s sort of tough to just instantly buy 1,000 ponies. Word spread quickly in agriculture circles that Ford Motor Company was buying ponies for a big promotion, so many less-than-scrupulous horse traders tried to cash in on Ford’s deep pockets and agricultural naivety. A fair number of the ponies weren’t terribly healthy, and needed veterinary care (like you mentioned, not quite in most car dealers’ area of expertise). Worse, some folks sold Ford juvenile horses instead of ponies, figuring that those fancy businessmen won’t be able to tell the difference. The lucky families who took one of those home were in for a big surprise!

Well, I guess I’d’ve fallen for it. I must be a city slicker; I had to go look up the difference between a pony and a horse.

I’m sure that if a company did something like that today, the animal rights organizations would be up in arms.

I assume back then Ford just had lower-than-average glue costs for a few years after the promotion.

As they should be.

Laying the bait . . .

That’s spectacular!

And that does point out something important — the pony thing wasn’t entirely random, because Edsel sponsored the Wagon Train TV show (hence the Wagon Train reference in the above ad, and actor Ward Bond’s presence).

The show was much more popular than Edsels, So that’s what led Edsel marketing employee Tommy Thomas to blurt out “let’s give away a pony” (referenced in LA673’s comment above), and with that, the PR folks hoped that more connotations with Wagon Train would lead to more sales.

It didn’t, of course… the TV show outlasted the Edsel brand by 5 years.

A wonderful fascinating history of an almost delusional design marketing approach. Makes new coke look like a moderate success! Thanks for the history.

When my wife was proofreading this article (for which I’m deeply grateful, since it became so long), she asked me what 20th century corporate flop was worse than the Edsel fiasco.

The only thing that came readily to mind was New Coke.

New coke, was not meant to be a successful launch. It was to change the original coke to corn syrup instead of sugar. The taste was noticeable so, they had to pull that stunt. Try Mexican Coke in the glass bottle vs classic coke.Mexican coke still uses sugar

There is (because of course there is) a ton of mythology around the New Coke thing. Coca-Cola started using high-fructose corn syrup in 1980, and stopped using cane sugar in 1984, the year before New Coke came out.

If one wants to pin New Coke as some kind of nefarious plot, it’s sturdier to surmise it was a publicity stunt (the you-can-say-whatever-you-want-about-Ford-cars-as-long-as-you-say-it-three-times-an-hour theory).

There’s a pretty good (and well-supported) Wiki article on the subject, which isn’t surprising; rigourously-researched books have been written about this what’s become a popular business school case study.

The Edsel dealership in Cheyenne was W. E. Dinneen. The company was a longtime local business – dating back to stable/carriage days. Prior to becoming the Edsel dealer Dinneen handled Plymouth and DeSoto from their attractive and historic red brick building at 400 W. 16th Street (Lincolnway). I have no idea how the deal was done to terminate Plymouth/DeSoto for Edsel.

Post Edsel Dinneen became the Lincoln and Mercury franchise for Cheyenne. Later they added Buick, Pontiac, Mazda and Subaru but the company is no longer in the car business. The original dealership building is now the “Wyoming Rib and Chop House”. The food can be pretty good but sadly the character of a car dealership is missing.

Wow, that’s one of the neatest car dealership buildings I’ve ever seen. Glad it’s been preserved.

This was a real pleasure to read, adding plenty to the tales often told. An especially nice job at the local-news human level with the dealerships, all of them representing someone’s risk/reward dreams and decisions. The businessmen are likely all gone now, but I suppose their (aging) children somewhere still have some photos or business records….somewhere.

I was alive then, but a few years too young to have taken in either the publicity buildup or how quickly sales stalled, all of it in not much time at all.

Bravo!

Very interesting article. The dealers who signed up for a franchise, and then had to actually sell them, tend to get short shrift in the Edsel saga.

In the end, the Edsel failure was better for the company over the long-term. Ford was trying to replicate the Sloan Brand Ladder, which was already collapsing in the late 1950s. With the failure of the Edsel, Ford wasn’t faced with keeping multiple divisions stocked with product by the 1970s and 1980s.

Ford found the alternative to the Sloan Brand Ladder with another vehicle that debuted that year – the four-seat Thunderbird. It was a fairly expensive car that was sold by Ford dealers. Ford thus proved that people would buy an expensive vehicle from a “low-price three” brand in sufficient numbers, if the vehicle possessed the necessary level of distinction.

The Edsel Show introducing Edsel to the country on TV was the first program to be video taped and replayed from the video.

The interesting story of finding the original tape is here:

http://www.kingoftheroad.net/edsel/edselshow3.html

that was Bob Rosencrans’ television first

the show was a great success, the car, not so much

he started MSG, BET and gave US C-Span among others

later owned Columbia Cable

>>[ A P P L A U S E ]<<

Wow! This is a fantastic article. I started out knowing not a whole lot beyond the Edsel being a misshapen, ill-conceived, short-lived failure; now I know quite a bit more and better.

was a horrendously unreliable copy of the perfectly dependable pushbuttons Chrysler introduced in 1956. Since we’re on the topic of the Edsel having…how did they put it in the ad? Ah yes: “the new ideas next year’s cars are copying”.

Thanks very much!

…remember, the Teletouch transmission makes shifting gears as easy as flicking a light switch!

Nice job, Eric. It takes a lot of time and research to put something like this together; writing it largely from the perspective of the dealers was a great idea that adds a refreshing angle to the Edsel saga.

Thanks Aaron! Yes, it took quite a while to do the research for this — I feel like I’ve been buried in Edsel minutiae for months. Glad you enjoyed the article!

The modern-day analogue that comes to mind is the Segway. The hype machine for that didn’t even say what kind of product it was going to be, only that it would change the world, or something similarly grandiose. As much as I’d enjoy a ride on one, the reveal was a let down.

This has been one of the best automotive stories that I have read in a long time-Excellent job!

Give away 1,000 ponies? Nah-I don’t see any problems whatsoever…..

Tastes like chicken. Actually I remember the great horsemeat debacle of 1974. Interesting times….

Terrific article and one I will go back to in the future.

I suspect that the core lesson to learn is that “doing more of the same thing”, albeit with a fancy grille and so on, is not the same as a truly new product. See Mustang for more information, and evidence that Iacocca at least got the point.

And Eric, we need to get together over a beer or tow, and I’kll give you the full story on Carr’s Motor Sales…;-)

I thought of you when I came across the Carr’s Motor Sales ad, so I’m glad you noticed it! Never knew you had a background in Lincoln-Mercury sales…

Fantastic, informative article, Eric! Well done!

This was a great article, and I learned a lot. I was 5 when the Edsel came out, and I still remember the hype.

While I applaud your efforts on this article, you have certainly tied a lot of ends together using a lot— and I mean a lot— of assumption and conjecture.

I am not going to get into alot of the forefront story or the story told for the later part of the Edsel debacle from your article— but I am going to note a few things regarding the dealer because I have spent 36 of my 44 years alive in Edsels and of those 36 years- I have been researching Edsel dealerships for over 33 years now. I am the Gilmore noted on the Edsel Dealership Directory pages you referenced in the comments above…

At any rate— a few corrections:

You noted and acted like it was rare for some of these Edsel dealerships to have been signed within a month of opening? No dealerships were officially signed until approximately 2.5 months before E-Day— and they continued at a rapid pace over those 75 or so days — few got even that much time, with a bulk of the dealerships being signed in the last 45 days before intro.

Of the many dealers which you could have featured, I find it odd you featured three dealers who in REALITY give examples of three different routes that happened to dealers overall, but yet in your article you basically make it out that all three flopped with Edsel.

That isn’t so.

Regarding Mark Edsel: Eisner was offered the L-M deal in Rockville, MD, because he shown great promise and potential as an Edsel dealer… when M-E-L Division was formed in January 1958, a plan was put into place to merge out Edsel only franchises into MEL— this was happening one of three ways. 1- The Edsel was given to the L-M dealership and the Edsel only franchise phased out- this was often the case with Edsel dealers just wanting out or if both the L-M and Edsel deals were successful in an area, the Edsel was given to L-M and the Edsel dealer was offered another FoMoCo franchise of some type in a nearby area.; 2- If the Edsel dealer in an area was outpacing in sales a facing Mercury dealer or if the area had a problematic Mercury dealer— or just didn’t have a Mercury dealer— then Lincoln and/or Mercury was given to the Edsel dealer if they so desired. (In my area, the Roanoke, VA, Edsel dealership was offered Lincoln-Mercury and turned it down— and gave up the Edsel franchise to boot all within a two week time period.) and 3- In a few rare instances, Ford managed to get the existing Edsel dealer and the L-M deals to Merge into one business. This did happen but it was rarer than the first two scenarios. Eisner fell into the first and second category— Mark was a strong dealer for Edsel by Eisner’s own account (I interviewed him before his death in May of 2007.) O’Brien & Rohall was the Arlington L-M deal and they, too, were successful. Ford maneuvered the deals so the O’Brien & Rohall got Edsel for Arlington and facilitated the deal for Mark to take over the Rockville deal moving Edsel to there with Mercury.

Your article implies that Mark was a failure with Edsel and his Rockville move wasn’t a step up— and it was. Had he been a bad dealer for FoMoCo they would’ve just forced him to hold the bag and gotten Edsel to O&R L-M and called it a day— in my research over the years I have seen that many times without a single offer to the Edsel dealer for anything else within the confines of FoMoCo dealerships.

Next, you mention that Mark sold Used Cars and kept his service department open while awaiting the introduction of the Edsel— um Eisner wasn’t signed with Edsel until August 23, 1957 (announced as the fifth dealer to sign in the DC area on September 1). There was only 11 days between being officially signed and Edsel’s introduction— those 11 days meant fast and major changeover for the Wilson Blvd. property— there wasn’t some great length in there for what you noted.

Lastly regarding the DC Area dealerships: You left off the 7th dealership— there were indeed 7 not 6— College Park, MD, was the home of Bowman Edsel which opened just after E-Day on Friday, September 6th.

Regarding Jefferson City, MO: Wellington got a buyout from FoMoCo – he gave a conditional resignation and when Ford met the terms he asked for and they had agreed to, the local L-M dealer Paden Motor Company took over the franchise. West Dunklin Street is now Missouri Blvd. The dealership building is no longer there. Missouri area dealers also took the train to Chicago. Out west where air travel was more efficient, dealers and their accompanying personnel were flown (ie the Southern California dealers were all flown to San Francisco for their showing).

Your notation about there being so many contests and giveaways is absolutely true— but you seem to miss the fact that many of these Grocery Stores and other businesses that gave away Edsels that year are the ones that spearheaded those efforts to draw the attention of the fact they were giving away the hottest new product at the time those negotiations were held. I would not take Wellington’s part in this Sav-Mor campaign as an effort on their part to generate more excitement— many of those give-aways were arranged by Edsel Division themselves— and they are noted with Wellington in the Sav-Mor ad. Common practice— not something that the dealers much sought after themselves.

Lastly, I don’t even know where to being on your Swearingen Story so I am just going to give the facts in full as I have written about in the past: Twin Brothers William and James Swearingen had been in the automotive business as partners in the Swearingen-Armstrong Ford dealership in Austin for almost 20 years when they parted ways with Armstrong in July 1957 to take on the Edsel franchise.

They found land and commissioned a state of the art building to be built specifically for Edsel. It opened on E-Day as one of the largest Edsel dealers in the South. (The dealership building WAS COMPLETED by E-Day- that photo you posted of the First sale was taken inside the dealership building that week! I’m not sure where you got the Spring 1958 part of that story but it is completely incorrect.)

Regarding dealers relinquishing Edsel you noted: “Most of the original exclusive Edsel dealers relinquished their franchises by the 1959 model year.” In actuality, by the intro of the 1959 model year (October 31, 1958), of the original 1,265 Edsel Division named dealers (those named pre Edsel introduction until January 1958 regardless of dual combinations with other FoMoCo products), only 44% (560) had relinquished their Edsel franchise. That number includes 9 dealers who signed to be an Edsel dealer before E-day but bailed before officially opening and 8 dealers who sold out to another entity. By October 1959, only 58 Edsel only franchises remained— 432 original Edsel Division dealers (34%) made it to the very end on November 19, 1959 still handling Edsel— 3 were Edsel only by that date. The other 430 had been signed as M-E-L by then or owned other Ford Motor Company deals which handled Edsel in a dual capacity from the beginning.

A few other corrections to your article regarding marketing elements: You note that Edsel Division “supplied” the Scale Model Edsels to dealers for giveaway— if only. Edsel dealers were required to BUY THOSE by the dozen and they were indeed billed for the cost as I have the invoices and paid receipts from dozens that several dealers bought.