I often have to pause mid-conversation and explain the rationale for something I just said to my wife, not because she doesn’t understand the topic, but because she doesn’t understand why I’m bringing up that topic. This is one of those times. Back in November, Roger wrote about a 1960s Humber Super Snipe, and I made a comment about rally driver Maurice Gatsonides and the 1950 Monte Carlo Rally. Being from the States, I had no idea that Gatso was somewhat more infamous in the UK for inventing the speed camera that drivers love to hate. Regardless, I did the first thing that anybody who was a part of that conversation would do and bought a 72-year-old, long-out-of-print translation of a book about Gatsonides’ adventures. What a guy!

I became interested in classic rallying back in the late 1990s, when Speedvision was a glorious channel on basic cable, and David Hobbs and Alain de Cadenet (RIP) would host programs that highlighted vintage rallies of the 1950s and 1960s (in addition to stock car, sports car, and Indy Car races). So I bought books, and one of my favorites was Graham Robson’s A to Z of Works Rally Cars (RIP, Mr. Robson – you were the best!). In this wonderful book was a car I had never heard of and I’ve still never seen – a 1952 Humber Super Snipe. The driver? Our featured Mr. Gatsonides.

Roger’s discussion of Humbers, as I said, brought all of these latent memories flooding back, and I found this old book very reasonably priced (although not common at all – good luck finding one now that I’ve bought this one!) on a used book website. Published in 1950, Gatso’s adventures were told by William Leonard and illustrated by Jan Apetz.

This book is such a fun (and scary) piece of automotive history and folklore! The action focuses on the immediate prewar and postwar period, and I learned three basic things from reading it: 1. Rally drivers straddled the fence between determination and lunacy. They were ALL tough, and many were (refreshingly) female. 2. One can learn a lot about the day-to-day anxiety of impending war by listening to a traveling rally driver. Gatso rarely (if ever) gets political, but it’s easy to see that life in Europe both before and after the war was stressful in a way that most of us would prefer not to consider. 3. Gatso had a ton of bad racing luck.

Like Dan Gurney and Mario Andretti at Indy bad luck. He only won one race in 21 chapters (a class win at LeMans in 1950 in an Aero Minor), although he would later famously win the Monte Carlo Rally in a Ford Zephyr.

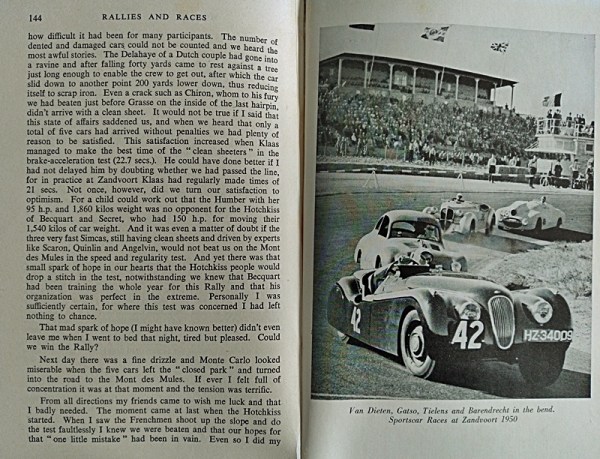

This is the 1950 Humber Super Snipe that Gatso used to ALMOST win the 1950 Monte Carlo Rally, and this is the car I fell in love with as a young man who couldn’t get enough of European rally racing from a time and place I could never visit but wanted to (not truly understanding the tense realities of the situation back then). I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a Humber in real life, but reading about Maurice Gatsonides’s exploits made it jump from the page.

I hope it’s OK with G.T. Foulis & Co., Ltd. in London that I reproduce the chapter on the 1950 Monte Carlo. The writing style reminds me of 1950s-era Autocar magazine – a unique combination of academic formality, conversational tone, and “down at the pub” in-jokes. The most engaging chapters are the earliest, where “Maus” was finding his footing as a professional. Some of the conditions he endured would send most of us scattering home. Another reminder of the tough conditions in rallying is the fact that many of Gatso’s friends and contemporaries did NOT make it home: rallying may not have been the bloodbath that was Formula 1 back in the day, but it claimed more than its fair share of victims on the icy roads of the Alps and abroad.

Gatsonides even produced a few versions of his own sports car (some with a strange center-mounted headlight), and there are stories about them in this book (he called them, appropriately, Gatsos). He apparently fell into some financial difficulties in the 1950s, but was able to market (with the help of his son) the speed camera that is so infamous in the United Kingdom. According to stories on the internet, he designed that device to help with his driving; by measuring his speed in certain corners, Gatso was able to determine the best line to take. His invention of the speed camera was in keeping with his reputation as a man who fastidiously did his reconnaissance work; he was certainly innovative and talented.

Mr. Gatsonides passed away in 1998 at the age of 87. What does a Dutch rally racer from the mid-20th century have to do with a guy who primarily collects American cars of the mid-20th century? Well, I always love a good story of good drivers and good engineers. Maurice Gatsonides was both.

As an aside, the featured photo of a 1950 Super Snipe is from Bonham’s. That car was auctioned in the UK this year and sold for 3,200 pounds. If I lived in England and knew about that auction, this car would have been mine. Even now it hurts to think about.

P.S. I tried to take decent pictures of my book, but a few things stood in the way. First, my scanner is unwieldy, so I didn’t use it. Second, my phone camera is cheap. Third, my interest in photography is akin to a folk singer’s interest in guitar playing; I’m only interested insofar as it can accompany what I’m saying.

Thats quite cheap for a tidy 50 Super Snipe, but of course once you have it the feed bill comes in and they are thirsty old tanks

Oh, I’m sure that the Humber would be an economy champ next to my new ’63 Riviera, or most of my old junk! 🙂

I’m sorry, I know this is completely shallow of me, but I just can’t-never-could take seriously a car called the Humber Super Snipe. Might be to do with those ‘snipe hunts’ they sent us on at summer camp.

I’m not exaggerating even a little bit to say I’d have an easier time with a Tooth Gnasher Superflash.

One word does make a big difference, doesn’t it? Exchange “snipe” for “snake,” and someone will pay you a million dollars for your rare Shelby (with his signature on the glove compartment, of course).

“Third, my interest in photography is akin to a folk singer’s interest in guitar playing; I’m only interested insofar as it can accompany what I’m saying. ”

What a great analogy!

I’m not at all a student of British cars but as a all around car guy, I am reluctant to admit that I’ve never heard of Humber or their Super Snipe. This relatively large English car looks rather American.

Thanks for sharing the Rally story. It is an interesting tale well told.

The portrait of Gatsonides, who I also am unfamiliar with, reminds me a bit of Robert Oppenheimer of atomic bomb fame. What kind of car guy am I that I’m more familiar with a 20th century scientist than I am of a famous race car driver of the same era? I may need to turn my card in.

I love that I can always learn something new at CC!

Thanks Jon! Speaking of Oppenheimer, have you seen the previews for that new movie based on him? I think I might have to watch that one once it comes out on streaming platforms; I’ve always been intrigued by his famous quote from the Bhagavad-Gita: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” The other day, I was watching a video discussing that quote and how his use of it might not mean what everyone thinks it means.

Thanks for the information on Gatsonides and his exploits – he certainly seems a bit of polymath and aside from his name and a rally association (and the camera link but not the reason) I knew little about him.

You’ve set off my interest – thanks again

You’re welcome, Roger…thank YOU for sending me down a path that “made” me buy an old book. 🙂

Early 1950s Humber Super Snipes were my parents car of choice. In Australia where I live they were expensive cars selling against Buick, Jaguar and similar. My parents first Humber was a 1949 Humber Super Snipe and his car very much represents my earliest childhood car memories. My parents only owned it for 2 years when it was traded in on a new 1952 Humber Super Snipe with the much improved Commer truck based ‘Blue Ribbon 6 cylinder engine. This engine was a massive improvement over the early side valve Humber 6 cylinder engine.

By the early 1960s Humbers were no longer keeping pace with automotive design and my parents replaced their Humber Super Snipe with a Chevrolet Belair which in Australia was a high end luxury car. Thanks for the childhood memories.