(first posted 9/28/2012) I love Studebaker. Pretty much any South Bend-built model gets my immediate attention, but I have to acknowledge that, in the end, Studebaker did itself in. We almost lost them in the ’30s, but thanks to the new management team of Harold Vance and Paul Hoffman–and in no small part, healthy refinancing and restructuring–Studebaker survived the Depression and by late 1933 was back in the black. Unfortunately, those same guys started making bad decisions that led to the last South Bend Studebaker cars leaving the soon-to-be-shuttered factory in December 1963; 1964 models, like this one.

Studebaker got off to a great start in the postwar era with their startlingly modern 1947 models, and with further advances such as a V8 engine and automatic transmission–both designed in-house, a major achievement for an independent–sold lots of cars through 1952, when Studebaker celebrated its centennial anniversary. Unfortunately, trouble was right around the corner. The all-new 1953 models–both the beautiful coupes and stubby sedans–sold less well than Studebaker hoped, and things would never be the same.

That’s not to say that Studebaker stopped making neat cars. Their classic Loewy coupes, handsome E Series (later Transtar) pickups, innovative Wagonaire and many other models were attractive and interesting–but sales continued their downward trajectory.

The Studebaker story is oft-told, here on CC and elsewhere, so I won’t go too deeply into it. That said, one big problem was that Studebaker didn’t control their costs. Whatever the workers wanted, they got, and with nary a cross word from management. That led to astronomical production costs compared with the Big Three, and Studebaker’s rapidly aging facilities complicated matters further. The success of the ’59 Lark provided a brief reprieve, but when the Falcon, Corvair and Valiant debuted, it was back to the same-old, same-old.

And thus do we come to the 1964 Studebakers. Brooks Stevens, the renowned Milwaukee-based industrial designer, was a godsend to small companies like Studebaker. He had quite a knack for taking a shoestring budget and delivering a major refresh that looked great. What would be his last assignment for Studebaker was the 1964 model refresh, seen here. There’s a 1959 Lark under there, but it sure isn’t obvious.

He first worked his magic in 1962, with the Mercedes-like 1962 Larks. They looked to be all-new, thanks to clever styling, but were the same old Lark. Sales increased over 1961.

That same year, perhaps his best design ever, the Gran Turismo Hawk, came onto the scene. The transformation from the befinned 1956-61 Hawk was remarkable, and a real beauty.

Studebaker had spent most of the early ’60s clinging to relevance. Had it not been for Sherwood Egbert, Studebaker may have had even less time left. But Egbert, going against orders to shut down Studebaker, instead tried his best to keep it going, hiring Stevens to come up with new styling, introducing the Avanti, and setting records at the Bonneville Salt Flats with Andy Granatelli-prepped R1- and R2-powered Hawks and Avantis.

Egbert did all he could to keep Studebaker afloat, but unfortunately his effort didn’t translate into any meaningful sales increase. Illness forced his retirement from Studebaker in November 1963; almost immediately, the Studebaker board approved shutting down South Bend in favor of limited production at their Canadian facility. The last Indiana-built car came off the line December 20, 1963. At the same time, production of all light- and heavy-duty truck lines, the Avanti, and the GT Hawk ended for good.

But not before the last “new” Studebakers came out in the fall of 1963. While technically still Larks, the name was not seen on the car. Instead, the names of different trim lines–Challenger, Commander, Daytona and Cruiser–were emphasized. Studebaker may not have had much time left, but they still had quite a good-looking car as well as attractive, colorful interiors.

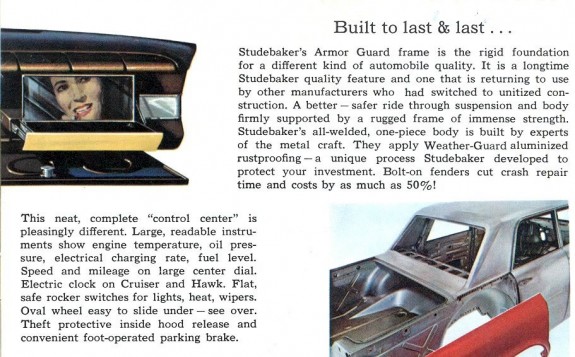

The instrument panel was particularly sharp. In contrast to so many other domestic cars, the Stude had full instrumentation. And the optional tachometer was placed right there on the dash with the other gauges, unlike the difficult-to-read, center-console-mounted tachs in some GM and Ford products. Despite all their troubles, Studebaker still offered many thoughtful, intelligent design features.

In addition to more modern, squared-off sheet metal, there was power if you wanted it. The aforementioned R1 through R4 power options resulted in a sedate little Studebaker that could potentially suck the doors off unsuspecting Sport Furys, Impala SSs, and Fairlane 500s. You could even get disc brakes, but you’d have to hurry, as only South Bend-built Studebakers got the R-spec equipment. The denuded Canadian-built 1964 lineup would be limited to bread-and-butter family cars, not hot rod Avantis, Larks or GT Hawks.

But if you wanted luxury and not a hot rod, you needed look no further than the Cruiser. As in the past, the Cruiser nameplate designated the finest Studebaker you could get. While previous versions of the Cruiser had merited a longer wheelbase than lesser Studes, the 1964 model had the same 113″ wheelbase and 194″ overall length as the other ’64 four-door sedans.

The attractive, new-for-1964 “Lazy S” hood ornament was indeed appropriate for the luxurious Cruiser; it also graced all other Larks except the entry-level Challenger model.

Cruiser features included a standard Thunderbolt 289 cu in V8 (although some export Cruisers were built with the six), plush cloth interior, wall-to-wall carpeting and extra chrome trim inside and out. Available only as a four- door sedan, the $2,595 Cruiser ran about $650 above the cheapest Lark, the $1,935 six-cylinder Challenger two- door sedan.

As with our featured car, most ’64s got a clock instead of a tachometer. I think this may be one of the most attractive instrument panels of the ’60s: all business, but with just enough chrome trim to let you know you’re in something a cut above.

I recently found this handsome Cruiser at the downtown Geneseo car show. Here you can see the chrome side molding unique to the Cruiser (although Daytonas used similar trim with a black-filled center), along with sail-panel “portholes” and the 1964-only trim panel between the taillights. The light-blue metallic paint glowed, and it looked perfect with its original wheel covers and whitewalls. I don’t know about you, but I’d take one of these over that red Chevelle sitting next to it. It certainly is rarer, one of only 5,023 Cruisers built for the year.

It was a valiant effort; but with South Bend shut down, already gun-shy Studebaker buyers became even more skittish. Ultimately, the diversification-driven Studebaker board got their way, and in 1966 the car division was shut down in favor of STP car care products, Gravely tractors and Trans International Airlines. But handsome cars like this true-blue Cruiser remind us of what was once the oldest auto manufacturer in America. Studebaker, you are gone, but not forgotten.

The 64 Studes are among my very favorite cars. I may be one of the few alive who actually spent time around multiple versions of these. The Studebaker-loving family of my best friend growing up had two of them – a brown Commander sedan (a low level 6/stick car) and a Daytona 2 door hardtop in this very color. The Daytona was a really cool car.

I have always wondered what would have happened if this model had come out in 1962 instead of in 1964. Yes, it was still kind of tall and stubby, but it had a modern greenhouse and was very nicely fitted out inside.

With apologies to my neighbors to the north, I have always considered these to be the last “real” Studes. The Chevy-engined 65-66 cars were a sad end. No more R engines, no more disk brakes or innovation of any kind. I will admit that the Chevy 6 was probably an improvement, but the Stude V8 was a good old engine. It’s funny that in another ten years, this car would have been back in style. Luxury in a compact package came back in a big way with the 1975 Granada.

I see that the brochure lists as available the R1-R4 engines. I doubt that any of the R3 or R4s were actually built. There were only a handful made and I would suspect that those found their way into Avantis or Hawks. The supercharged R2 was also probably pretty rare.

Damn you, Tom – now I am going to spend all day lusting over this beautiful blue Cruiser.

Supposedly, there were 9 R/3 production cars, and 1 R/4, but Paxton sold many more crate engines- something like 120 R/3s and 7-8 R/4s. Oh, and you’re right about the R/3s- all 9 were in Avantis. The R/4 was a Lark convertible, though.

http://www.studebaker-info.org/Rseries/R3Misc/R-enghistory.txt

At least one ’64 Lark R3 was produced – a 2-door hardtop or coupe. It’s been featured in Hot Rod and Hemmings Muscle Machines (Aug. 2004) – gotta be the rarest muscle car there is. One made! Even though anyone could order an R3 in any Lark, Hawk, or Avanti in ’63 and early ’64, the high price (twice what the R2 upgrade cost) and inavailability of air conditioning drove away buyers.

Thanks for the tip. I searched out the Hemmings piece, and it is indeed a fascinating story. http://www.hemmings.com/mus/stories/2004/08/01/hmn_feature20.html

“I don’t know about you, but I’d take one of these over that red Chevelle sitting next to it. It certainly is rarer, one of only 5,023 Cruisers built for the year.”

Not me by a long shot. Give me the Chevelle any day. Studebakers were obsolete for years by the time they called it quits, regardless of styling – which in the case of the hardtops was superb. Being a “rare” model doesn’t make it good.

There’s good reason why the minor players like Studebaker, Hudson, Nash, Kaiser and anyone I missed all faded away. I don’t miss them…except for the Avanti.

“There’s good reason why the minor players like Studebaker, Hudson, Nash, Kaiser and anyone I missed all faded away. I don’t miss them . . . ”

Ow Ow Ow Ow! C’mon, Zman – it’s Friday. No need to kick the poor hapless Studebaker. 🙂

Yeah, the world is a better place with only Malibu Colonnades with fixed rear windows.

Gee guys, I didn’t say I HATED them!

Of course, as a lover of most things old and especially quirky, I just resigned myself to the cold, hard reality. That, and the fact that I never had an opportunity to drive a Studebaker…or a Nash…or a Kaiser…or a Hudson.

But I sure enjoyed driving a buddy’s dad’s 1961 Rambler Classic, a friend’s 1959 Volvo PV544. Now those were pretty cool!

I bet if you drove a Studebaker, you’d feel the same way.

Driving a Studebaker like this one will usually make you a fan. Remember my uncle and I being shown a brown ’64 Cruiser new at the dealer’s. My uncle wound up buying a new Comet Caliente 6 for much less though. Sorry he didn’t buy the very elegant Cruiser.

I was born in South Bend a few years after the plant shut down, and during my 1970s kidhood Studebaker cars were a very common sight on South Bend streets. That started to peter out during the 1980s as mechanical issues, spotty parts availability, and rust did most of these cars in. When I go back home today (my parents still live on Erskine Boulevard, named after former Studebaker president Albert Erskine) of course no more Studebakers prowl the city’s streets. Yet the town still hangs onto its Studebaker heritage — often in an unhealthy way, wishing that manufacturing on that scale would return. My hope for my hometown is that it will finally move on after 50 years.

Some of my first contributions for CC last year came from a trip I took to South Bend. I found a couple of cars there, but they were not daily drivers.

https://www.curbsideclassic.com/automotive-histories/studebaker-in-south-bend-going-going/

As a native, I would imagine that you could go into a lot more detail than I did.

The funny thing is that as a child I found the Studebakers still being driven to be hopelessly outdated and therefore unexciting. Also, the trappings of Studebaker left in town were just part of the fabric of town, and I did not really realize how special it was. For example, the elementary school I went to, a stunning red-brick building with a slate roof that looks kind of like a castle, was built with significant funding from the Studebaker family. (Some photos: http://blog.jimgrey.net/2010/11/08/school-renovation-completed/) It is only now in my middle age that I appreciate what I had growing up.

Today, that 64 Stude is fantastic. I’d love to own it. But speaking in 1964, this car was a ho-hum car, much like a Rambler or a Big Three compact. I’m sure the Studebaker was not cheap, not like base Falcons, Novas, and Valiants. The Studebaker looks very well made. I was 12 in 1964, and I can recall a friend (around that time, give or take a couple years) saying his aunt bought a Studebaker. I wondered why anyone would want one.

Who would buy the Stude, when Impala SS coupes and sedans might cost a few dollars more? Maybe the guy that wants a Mercedes. In the 1960’s, those guys were few and far between. The GT Hawk is a fantastic car, but also was not right for the times.

Studebaker was not part of the space age 1960’s. In 1975, the 64 would have sold, like the Granada. The Studebaker is a better car than a Granada could ever be.

Studebaker, wrong place and wrong time. Too bad. The Avanti, however, was right for any era. The car, in an affordable price range, would sell well.

The 1964 redesign made the aging Studebaker body somewhat more modern looking but it was still hopelessly old school. By that point even AMC had completely updated its line up, so the Studebaker looked even more ancient. In a way it might have been better for Studebaker to go the VW route of not even trying to offer current styling. Doing halfway measures just underlined how much they had fallen behind.

It didn’t help that Studebaker had upscaled its pricing into the mid-sized market just as GM came out with a splashy new body that offered in four — four! — distinct brands. Talk about carpet-bombing a market.

The other thing is that the Studebaker didn’t have enough uniquely valuable qualities to capture the public’s imagination like Rambler and VW had. Gas mileage wasn’t so hot from the antiquated six, handling was among the worst, and the lack of a step-down chassis didn’t give the sedans as much room as you’d expect for such a tall and boxy car. And whereas Rambler could crow about technical features such as unit-body construction, the Studebakers were still based upon the notoriously squeaky “flexible-frame” dating back to 1953.

Perhaps the only hope for such an old-school platform could have been to carve out unusual product niches, such as a Wagoneer-style four-wheel-drive wagon and a compact truck (with better styling than the strikingly awkward Champ). Indeed, I’ve wondered why Studebaker didn’t grab Kaiser-Willys if its board was so intent upon diversifying out of passenger-car production.

The brilliant (crazy?) inspiration stikes: Studebaker should have partnered with International Harvester. These boxy sedans with flat side glass would have been perfect complements to International’s Scout and Travelall. Imagine the small (but heavy) Stude V8 in the Scout and the Binder’s 345 or 392 in the Cruiser and GT Hawk. The Travelall could have come in a WagonAire model with a sliding roof. Andy Granatelli could have run R9 Travelalls at Bonneville and one could have paced the 1968 Indianapolis 500. I’m getting giddy here. Plus, they both had already figured out how to make their vehicles rust quickly enough that they were ready for replacement when the loan was paid off.

+1 Brilliant! Someone get the photoshop machines warmed up!

There is a IH-Studebaker connection. They used the same supplier for hubcaps. Those on today’s feature car were also used on late 60’s internationals less the lazy S die in the center. With the dies for the “fins” removed they lived on until the 71 model year.

The 60’s full size line did not rust that fast, it is more common to find a low rust 61-68 truck than a 69-75.

Golden Hawk hubcaps showed up on Lincoln too.

Did any of the Checkers use this style of wheelcover? (the one on the above Lincoln)

I know that the heater unit on my 1947 Studebaker Truck was the same unit used on the IH Light Duty Truck of that same era. You would be surprised to find out that a lot of parts were had from a third party distributor and rebadge to fit the particular need. Look up vintage Kleenex tissue dispenser for cars. At one point all the major players offer a nifty flip down, chrome faced tissue dispenser to mount under the dash. Only difference was what name was inlaid in the chrome face…..

“+1 Brilliant! Someone get the photoshop machines warmed up!”

Ditto!

Sorry Zman, but that would be a mimeograph machine.

Tying up with IH does make a certain historical sense. Studebaker was founded in 1852 as a builder of wagons for farmers, miners and the military. By the 1870s they were “the largest vehicle house in the world”. (They even offered broughams.)

One other option is that Studebaker could have used its huge pile of tax credits to buy the country of Albania. Then they could have moved their entire South Bend operation there — production, design, everything. Costs might have been so low that the Avanti would still be in production. Raymond Loewy might have been declared a national hero. Sherwood Egbert might have had much better medical care and lived to a ripe old age.

The possibilities abound.

I could see it. Then, when Chrysler was on the ropes in the 1980s, it could have just bought these 64s (still in production, of course) and re-badged them as Dodge Diplomats. Hardly anyone would have known the difference.

One of my brothers had a ’61 Lark. I had a ’63 Rambler classic. They are different sized cars but we made comparisons anyway. The Lark drove and rode like a buckboard. It was high, and “truck like”. The Rambler was almost modern -by the standards of the ’80s, when we were comparing these cars.

maybe the guy who wants a Mercedes We had neighbors in Iowa City, Germans, who was an engineering professor. He drove a Flossen Mercedes, and he bought his wife a ’64 Daytona hardtop coupe. There’s no question that the Studebake had a certain appeal as a domestic alternative to the Benz. BTW, that Daytona was a sharp car. As a kid, I realized it was a “Stupidbaker”, and doomed, but I liked it regardless. Very nice interior, especially that dash.

Didn’t Studebaker and M-B share showrooms in the early ’60s?

Yes – from 1957-63 Mercedes-Benz Sales, Inc. was a subsidiary of Studebaker-Packard (later just Studebaker) Corporation. Dealership franchises were obtained from Studebaker during that period. M-B got its own sales organization in the US in 1963.

In my hometown of Fort Wayne, Indiana, the M-B dealer well into the 1970s was at the location that had been the Studebaker dealer before that. Although it was before I was old enough to pay attention, I suspect that it was a dual dealership before Stude was shuttered.

Then… (Rasmussen Studebaker)

Larks and 300SLs in the same showroom, wow.

…and now. (Rasmussen’s Mercedes-Benz of Portland)

A few months ago, I went golfing with some old pals from college. The “golf” part was unmemorable, but I was really distracted by an abandoned 1966 Studebaker on the periphery of the golf course. It’s fairly solid-looking, even though it appears to have been sitting there for years. But the most distressing thing about this car is that it’s located on a flood plain; this spot often experiences major flooding, and the body and interior of this vehicle bear witness to that pattern. Like meeting a friendly homeless dog, I sooooo wanted to take this car home with me. Along the Ohio river at Vienna WV (click image to enlarge).

Exactly the way I felt when I found this one.

https://www.curbsideclassic.com/blog/cc-outtakes/cc-outtake-1964-studebaker-cruiser/

Is the Studebaker considered a hazzard or in the rough? Whats the par on the Stude?

It’s way in the rough, but mostly an area used for practice swings. It’s next to a some old out-of-service golf carts and lawnmowers.

What a pity. Sitting abandoned on a golf course. This car needs to be taken home by someone who can do just about everything himself. Authentic restoration would not be feasible. Maybe, a good idea would be to find a modern vehicle, and alter the Stude body to fit. Just like fitting the kit car 57 T-Bird on a VW or Pinto chassis.

I knew a guy that could do it, but he has passed away. Only drawback, the Herculean effort required would only be valuable to the beholder.

Perhaps it was performed with Brook Stevens’ direction, but I believe that this facelift was the work of Gene Requa. He was driving one of these that he had modified to reflect the much wider taillights form his sketches when I met him a few years ago. Sadly, Gene died shortly later, but he certainly convinced me that this car was his design.

http://www.delmartimes.net/2009/08/06/legendary-del-mar-figure-gene-requa-dies-at-94/

The articles written upon his death all refer to a Hawk that he left behind, but the car I saw him drive was clearly a Lark sedan, I think a 1964.

You are right ZM. There is a reason those peripheral brands faded away. IMO it was $. I am not much for handouts but after several years of watching the handouts and/or low interest loans of the big three I think there might have been cases that were just as well suited as Chrysler, Ford, and GM. I know Ford wasn’t as publicized but do seem to recall there were some big loans.

Hudson, Studebaker, AMC were my favorites as a kid. I wonder where we might be if they had been helped to survive. Just to be Honest the Saturn S series was very high on my list lately. Owned two of them in the late 90’s and early 2k’s. That’s a whole nother story. I am not that big on buy american first as my Nissan will attest but the landscape sure is different from when I was a kid. I sort of miss that.

Studebaker, Nash, Hudson, and Packard was George Mason’s original plan for American Motors. They might have made a nice brand ladder with enough platform and engine-sharing scale to make it. Between Mason’s untimely death and CEO egos it was not to be.

The Big Three could have been GM, Ford and AMC, and we’d all be pining over old Plymouths and DeSotos.

Aren’t we pining over old Plymouths and DeSotos anyway?

Love these quirky old Studes…There is a guy here in Tigard that has a collection of them, and I see them on the road quite often

This summer, after my wife picked me up at the Portland airport, we headed directly for the Apple store in Tigard on our way to Cannon Beach. I had forgotten to bring along the power supply for my MacBook Pro. When I recounted this tale to our son who got his masters at the U of Portland (as did his wife), he laughed out loud. My wife and I pronounced the name of the town as “Tiggard”. My son said that it is pronounced “Tiegard”. Correct me if I’m wrong.

The conglomarate that owned Stude wanted out of the car biz and simply starved it to death. Seems like they just gave up.

They continued on with STP products, etc. Now STP is owned by another company.

Conglomerates were the curse that “businessmen” laid on US companies in the sixties and seventies. Another egregious example was RCA, the color TV powerhouse and owner of NBC, who acquired Hertz rental car, Banquet TV dinners, Coronet carpets and lots of others. Press said RCA stood for “Rugs Chickens and Automobiles.” Those people ended up in charge and drove RCA straight off a cliff. The fact that carpet and frozen food guys knew nothing about the electronics business meant nothing to the money men who got the power.

Same story with Studebaker and countless other American manufacturers. Car guys running Japan’s automakers and electronics guys running Japan’s TV makers took their places in the market.

You’d think they’d have learned not to let money men run companies, but as we all know they forgot that lesson very quickly. Don’t get me started…..

Forerunners of Cerberus….

Precisely.

Old Japanese conglomerates like Toyota, Mitsubishi, Kawasaki, and even Samsung and LG (though not in the auto business) would respectfully differ. Even the Indian Tata sells a lot of stuff from table salt to steel to cars and trucks, under the same trademark even, and has also founded and owns India’s largest outsourcing/IT Consultancy firm, called (unsurprisingly) Tata Consultancy Services. It appears conglomerates and the money men running them don’t seem to work only in the US. I think it has more to do with the money men being greedy thieves rather than the conglomerate business model itself.

Let us not forget that for many years, even the big three got in on the act, as well: For example, GM owned Frigidaire, and Ford owned Philco. It seems as though Chrysler diversified itself through expansion, versus acquisition, as Airtemp and the aerospace division were largely homegrown (with some help from the military).

Indeed, though there’s good commonality between making refrigerators (don’t forget Kelvinator) or air conditioners and making cars. They’re all durable consumer goods, sheet metal boxes with mechanical components inside. Frigidaire probably helped GM get a good price on steel, etc.

Every automaker kept defense contracts after their work in WWII and Korea. When it was good, it was very, very good (cost-plus). When it was bad, well … in 1953 Eisenhower named GM head Charlie Wilson his Sec. of Defense. Packard depended heavily on engine contracts that suddenly went away. (“The Fall of the Packard Motor Car Company” p. 118, on Google books.)

Remember owning Frigidaire also was very useful when air conditioning started appearing in cars.

Don’t forget IH they had a foray into Refrigeration too, but in there case it made a little more sense as they were aimed at farmers.

The automotive division of Studebaker was doomed regardless of whether the parent company diversified. The diversification effort was an attempt to save something for the stockholders when the auto division went out of business. Studebaker Corporation existed for several years after the cars were phased out, eventually disappearing in a 1979 merger, if I recall correctly.

Over the long run, the independents could not compete with GM and, to a lesser extent, Ford. “Car guys” at the helm would not have made much of a difference. AMC succeeded for several years by avoiding direct competition with GM, but once GM invaded the intermediate segment with the all-new Chevelle/Tempest/F-85/Special in 1964, AMC’s days were numbered. The Rambler Classic and Ambassador from 1963-66 were attractive cars in many ways, but they looked dull compared to a Malibu or a GTO.

I don’t even think that merging all of the independents in the 1948-50 period would have changed the ultimate outcome. To some extent, they competed with each other as much as with the Big Three’s various divisions.

AMC bought time by basically killing Hudson (shuttering its plants and phasing out the old Stepdowns and the Jet) and using the Hudson dealer network to sell Ramblers and Hudsons with Nash bodies.

Studebaker-Packard, under James Nance, attempted to maintain two separate production bases and two separate car lines (with unique drivetrains and bodies), and ended up burning through all of its available cash. Adding two more companies to the mix would not have made consolidation any easier or quicker.

The merged companies wouldn’t have been as big as Chrysler, and even Chrysler ultimately couldn’t keep up with GM.

I have read that most of Studebaker’s diversification involved the need to use up tax credits due to losses. My understanding is that due to several years of major losses starting in the mid 50s, big tax credits were rung up and that those had a limited shelf life. Studebaker was not making money to offset the losses against, so they cooked up deals to trade the tax losses to other companies in exchange for ownership positions.

By the 1980s developing and building a new car became a multi-billion-dollar proposition. For example, the 1986 Taurus. None of the independents would have made it that far. Even Chrysler would have closed without help.

Look at what AMC was like by 1986, kinda in the same shape as Studebaker, rehashing an old platfom again and again, from Hornet to Concord to Eagle, ancient trucks and full size suv’s, the only saving grace was the downsized Cherokee and CJ’s,thats what other independents would have been like by 86.

Our business schools have been failing us for generations.

Though their graduates seem to make out pretty well for themselves.

Which conglomerates?

Specify. Studebaker-Packard, soon to be Studebaker-Worthington, was a conglomerate in its own right. Soon to be swallowed by other conglomerates…by its OWN failings.

Its failings…were its management’s failings. Small-minded people focused on retrenching. It’s really the difference between expanding businesses and contracting ones.

Conglomerates can fail. Beatrice Foods imploded. A business…is the sum total of its management talent and intelligence.

Love that instrument panel. Flashy (but not too much so) and very functional. I miss that part of automotive design; now all instrument panels seem to come from the same factory in China, and probably do.

“It was a valiant effort…”

No pun intended? 🙂

I remember lusting after a 1964 Daytona 2-door hardtop with a 4-speed and a red interior that I saw on a car lot when it was a couple of years old. I owned a 1965 V8 4-speed Barracuda at the time.

By the way Tom, outstanding article. I love the way you use the brochures.

God I want the car that is being featured. Although I do see certain angles from which it reminds me of the Volare.

Believe it or not, a neighbor who was a U.S. Secret Service agent was issued a ’64 Stude as his “cmpany” car. Only a Rambler Classic would have been more low-key.

Wow full instrumentation floor shift and incidently front row grid position for the Bathurst car race for 65, these cars were used as police cars in OZ being about the only factory V8 available untill 66 with the 273 Valiant AP6.

I very much like these cars but know little about them. The last Studebaker front end reminds me very much of the Opel. Pic is from fahrzeugbilder.de

Also the 67 Chevy pickup.

From the moment Studebaker-Packard-Gravely-Worthington-STP-Onan…decided to close South Bend…the auto business was a dead issue. Eggbert, sick as he was, was made the sacrificial goat. His replacement, Byers Burlingame…was about as imaginative as his name implies. His role: Get out of autos; close the business without lawsuits.

Gordon Grundy misunderstood. He thought by producing a profit the Hamilton plant could be kept open. Poor, benighted Canadian businessman he was…didn’t see the big picture.

The company, from about 1960, when they saw the falings of Studebaker’s books and the prospects of the business and the labor demands and the problems of the former Packard brand…THEY WANTED OUT

The 1964, 1965, 1966 models were to give legal cover. Nothing else.

Why would anyone name a company “Onan”? Onan was a biblicical jerkoff. It’s like deciding Wanker LTD would be a good corporate name. Jeesh, flog my dolphin!

> That same year, perhaps his best design ever, the Gran Turismo Hawk,

> came onto the scene. The transformation from the befinned 1956-61 Hawk

> was remarkable, and a real beauty.

Amen. I can’t stop lusting after that car, even with its flexi-frame and

no AC(?).

You are in luck! Studebaker offered air conditioning from the factory in the early 60s. I do know that in the Avanti, if you wanted the supercharged R2 engine, a/c was not available because the blower took up the space needed by the a/c compressor. The same may have been the case in the other cars.

Brooks Stephens was certainly a very talented designer who with very limited resources did a very nice restyling job on the Hawk and the Lark, I always liked the looks of the ’64 Daytona coupe. Unfortunately, they were nice bodies sitting on basically ’53 mechanicals. The six wasn’t a especially good engine being a ohv grafted onto a flathead engine. The v-8 engine was the size of a Cadillac engine with the displacement of a Ford. Building the Starliner was probably a mistake-as attractive as it was it was a low volume seller and Studebaker really couldn’t afford two separate lines. It certainly didn’t help that management gave the union just about what ever they wanted, and generous dividend payments to keep stockholders happy meant there was little money for new designs or plant modernization.

One of my Little League teammates in Mexico City’s father was THE Studebaker agent for Mexico. He began showing up at our games on weekends with a stunning gen 1 Lark V8 convertible. Black body with a red interior. Full hubcaps with whitewall tires. Definitely an object of lust. The car was sold quickly to a customer who, in very short order totaled it. Bummer.

I really like these. Reminds me of an Art Deco Compact Fairline, but better. I’d have one. Beautiful color, too.

i dont think many relise too , just how fast some studes were,, we had a r1 289 v8 auto lark up to 140 mph …the so called 240 hp motor so claimed was really about 254 hp…and r2s and r3s were more than stated…up to just over 400 hp and some r5s tested out to 664 hp plus so yea.. with tall diffs from 2,6 to 3.08 they had a good top speed…better than many in fact…not many studebakers fall under 100 mph and that includes the six 169 cu.in pete

I think these models would have looked more balanced in the rear with the bumper moved to just below the tail lights, as they would have in 1967 if not for the BofD. Burrlingham was an old Packard man, I am sure he got satisfaction killing the murderer, in his opinion. Anyway, with the tall square roofline the rear was too high and square. Raising the bumper made a whale of a difference. No matter, still handsome cars, even today, The Wagonaire is truly an amazing car in many respects.

I owned a 64 just like the one published. It had 76K original miles. It was built in aug. 1963 in the South Bend plant. It had the original Studebaker 259 V-8 and 3-on-the-tree. Let me tell you that the little car was my favorite. (I also owned a 1970 Mustang with 351 Cleveland, 1972 Monte Carlo with 350 and 1968 Galaxie with 390). The Stude was a piece of history, but also a very light, quick car. It was very dependable-once started in am, cranked on 1st try for the rest of the day (even in sub-zero South Bend weather). If I could find that car, I would buy it again.

If you want to see a car that is almost a mirror image of what Studebaker could have been, even should have been in the sixties, look at at the Australian Valiant. From the moment it was introduced in 1960, it was Studebaker, only a better version. Studebaker built cars down under through the 65 model, no 66’s, guess that was a hint. Had Studebaker shifted production to Australia rather than Canada, they may have done better. Those Aussies have some really outstanding Studebaker’s. It must have been confusing to have so similar cars on sale. Studebaker’s Wagonaire would have been outstanding on this platform. What a pity, if Studebaker had a little more money. Actually they really did have the money. The Corporation was making huge profits in the mid sixties, the Board just would no longer invest in the auto division, a slow withering death, just like Packard.

There was a theory put forward, either here or in some other forum, that once Egbert was out of the picture the corporation only kept auto production going to avoid being in breach of contract with the CAW and especially the dealers. I see nothing here that convinces me that wasn’t the case.

I’ve read one or two articles over the years that suggested or wondered about a merger of Studebaker, Packard, Nash and Hudson. The consensus seemed to be that putting together four basically sinking ships would have been a disaster right up there with that grand-daddy of maritime disasters, the Titanic. Four distinct corporate cultures, four weak corporate structures, a dearth of design talent, little cash, and probably a fair number of retirees to support. It makes for interesting speculation on what might have been, but if these companies had had the resources and imagination to have made it on their own, they would have. The loss of each of them was sad, in its own way. I’d still rather remember them as they were, and for what they made. They will forever be part of the tapestry of the auto industry of the first half of the twentieth century. RIP to them all!

I think you paint the picture a bit blacker than it was. In 1948, when George Mason first proposed a merger (starting with Nash/Packard), all four independents were flush with wartime cash and bursting with engineering talent (47 Studebaker, 48 Hudson, 49 Nash, Packard’s Ultramatic, 50 Rambler, etc.) By the time the various personalities were ready to deal, things had deteriorated, thanks in part to the Ford/Chevrolet price war that decimated the independents and Chrysler to a lesser extent. If things had followed Mason’s schedule, the resulting AMC might have been better positioned to compete and to then take advantage of the prosperity of the mid-50s.

My first toy car as a child was the Studebaker Wagonaire by Matchbox. I loved it immensely so I always have a soft spot for the final Studebakers.

I hadn’t realized till learning more about them at CC that their mechanicals were so out of date. Loewy did a great job on a shoestring budget.