There are few sounds in the garage that are more heart-wrenching than that familiar “thunk” a Ford oil pump driveshaft makes when the distributor extracts it from its home in the oil pump and deposits it in the oil pan. If you’re lucky, it gets hung up on a surrounding hunk of iron and you can fish it out with a plastic tube or a telescoping magnet. If you’re not, you’ll be reading up on how to remove the oil pan in-chassis. Both of these unfortunate events can be avoided by simply installing the driveshaft as Ford Engineering intended, but you may not be so lucky if someone else built your engine.

I’ve suffered through this torment with two different Ford engines, a used 302 that lasted a few hundred miles and my ’63 Thunderbird’s 390. Looking down where the distributor is normally located, you can see where the oil pump driveshaft waits to be engaged to the distributor through a boss that is cast into the block (which also serves to support the distributor shaft/driven gear). The distributor drives the oil pump by engaging the hex of this shaft. The shaft, however, loosely rides in the oil pump; in other words, it is free to be removed from said oil pump if appropriate precautions are not taken to avoid it.

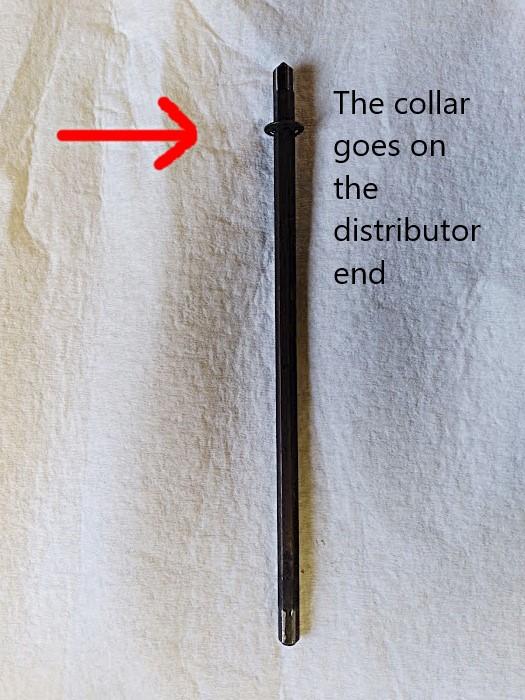

Fortunately, Ford employed engineers who solved this problem when they designed their engines. This is a Ford oil pump driveshaft. The small collar is located on the distributor side of the engine, where it is designed to “grab” the aforementioned boss on the block when the distributor is removed, trapping the driveshaft between the block and the oil pump. The distributor end is also beveled to ease the installation of the distributor. Pretty simple.

Ford even explains how to position the collar in the shop manual (this one referring to the 1965 Comet, Falcon, Fairlane, and Mustang). Motor Manuals also verify this method for installing the oil pump driveshaft.

The 1962 Thunderbird shop manual is inexplicably less clear in its text, but this diagram clearly shows that the collar should be oriented toward the distributor.

As a third source, I’ll cite Steve Christ’s How to Rebuild Big-Block Ford Engines. His explanation verifies what the shop manual says, but with a warning tone that is closer to mine.

Unfortunately, at least two engine builders in the world have installed Ford oil pump driveshafts backward, and my Thunderbird is currently running around with this unfortunate mishap waiting to ruin my day at any turn. I’ve been dealing with distributors in an effort to solve an ignition-related quirk in my T-Bird that I brought up last fall. Honestly, I don’t know how an engine builder could possibly do this incorrectly, but I have proof that someone did: I’ve fished the driveshaft out of the depths of that 390 with a magnet at least twice by now. (It’s like playing the old board game “Operation,” tongue hanging out on one side, one eye closed…Buzz! Damn it!)

It would be easy for one to say, “Aaron, why don’t you simply remove the oil pan and make things right?” Well, removing an oil pan in-chassis on a ’63 T-Bird involves a date with my engine hoist to, at the minimum, raise the engine up high enough to remove the pan. On top of that, resealing the pan underneath the car is not as easy as one may hope. Therefore, there’s a little laziness and inertia on my part, along with a little wariness. I’m of the mindset that the fewer things you disturb on an old car (if it’s not absolutely necessary), the better off you are.

Regardless, this is a problem that is so easily avoided when building an engine that there’s no excuse for it, and it certainly makes one wonder what else the engine builder may have done incorrectly.

Many people have derided Ford’s method of driving the oil pump as being somewhat dinky, but that’s beside the point. For decades, that spindly little driveshaft has done a perfectly serviceable job of keeping millions of Ford V8s on the road, and it should be foolproof under normal use and when installed as the factory intended. Unfortunately, Ford has no control over who turns the wrenches on their vehicles, and this is one case where reading the directions can save someone from a pretty bad day in the garage.

Note: I am not a professional mechanic; I almost exclusively work on my own vehicles for my own satisfaction (and because I could never afford my fleet without being a reasonably competent mechanic). The author and the website take no responsibility for your mechanical misfortunes.

Even If installed with the Tinnerman retainer on the pump end how could it slip past the gear housing cover and end up in the pan?

There is nothing securing the shaft itself to the pump itself; it’s a slip fit. The shaft’s diameter is smaller than the distributor “boss” in the block, so the distributor can pull the shaft right up through that hole, disengaging the shaft from the pump.

Oldsmobile motors use a similar 5/16 hex drive with the same pressed-on retainer. The retainer is actually used to prevent the drive shaft from dropping out of the block when it is being assembled on an engine stand with the bottom up and the distributor not yet installed. Unfortunately, the drive shaft ALWAYS gets stuck in the distributor gear, and you’re forced to pull the distributor and shaft out of the motor while sliding that retainer down the length of the shaft until is drops into the pan. On my Oldsmobile builds I never use the retainer and just drop the drive shaft in from the top after installing the oil pump.

I’ve never had the problem you describe happen to me on Fords, but that sounds like a damned if you do, etc. situation on Oldsmobiles. If the shaft sticks in the distributor the way you describe, the only problem when pulling the distributor would be hood/firewall clearance, I guess (if you leave the collar off).

Do manufacturers make video versions of their shop manuals nowadays? For the last 15 years or so, I’ve generally searched for Youtube videos to school me on how to do unfamiliar repairs or maintenance on my car, which I find much easier to follow than printed manuals, especially those lacking clear illustrations.

I have one bad memory related to this. Mid 70’s working 2nd shift for Greyhound. Fellow worker couldn’t get the distributor back in his 390 in a 67 Ford Galaxie. We got of work at 1:00 am, off to his place and fiddled around with that blasted distributor until about 3:00 am and finally the distributor dropped in the hole, fired it up, set the timing and headed home to get some sleep. I’m guessing the shaft may have been installed upside down. That was probably 47 years ago. Worst distributor ever and I had a ton of them out in my career.

It does make you feel like you don’t know what you’re doing when the distributor just won’t seat (that happened to me the most recent time I had the distributor out – I didn’t hear the shaft come out of the oil pump). Definitely make a note somewhere for your 428! 🙂

P.S. Hopefully I remember this when I pull my 428 for some much needed work.

Pffft ~ only poofters read the manual (/SARC./)

Picture # 3 shows as ready to fail original drive shaft ~ they wear until they slip in the oil pump, causing engine seizure from lack of oil….

I remember this occurring many times in the 1950’s to otherwise perfectly good running Fords .

-Nate

I went digging through my parts stash for an oil pump driveshaft for pictures, and the one you referenced is probably the original from my Mustang’s 289, so it would have had about 135,000 miles on it.

You did realize I said sarcasm, right ? .

I like the aftermarket design one .

-Nate

Thank God for You Tube!!

I’ll watch three different videos on how to make the same repair on my car.

Each will cover the quirks and surprises waiting for you before you even turn a wrench.

Has saved me sooooo much grief.

Nice article and very informative! YouTube is a godsend, though sometimes the people there don’t know what they’re doing either!

+1 on the do not disturb more than is absolutely necessary on an old car!

Thanks! YouTube comes in handy for a variety of little jobs (recently, remembering how to replace the pullcord on my old lawnmower). I don’t usually go there for old car stuff for the reason you mentioned; the people making the video are often working their way through the project for the first time.

I recently resealed a power steering pump from an ’88 5.0 Mustang, and I watched a video on YouTube to verify something (it was my first time doing one, and I didn’t have a manual for the car). The guy making the video seemed to take a wrong turn somewhere, but I didn’t bother going back to verify. 🙂

“the people making the video are often working their way through the project for the first time”

I like to think of those as a low-effort way to eliminate some rookie mistakes when I do the job after watching the videos.

Given that the shaft can installed either way, would it have worked for Ford to manufacture the shaft with a retainer at both ends?

They would have to use some other method of retaining the shaft at the oil pump, because the problem is that it gets pulled up and out of the pump itself. There are certainly more foolproof ways of doing it; for example, my Buick 300 uses a long shaft on one of the oil pump gears to engage with the distributor. Therefore, there are only two pieces instead of three to worry about. Of course, many have criticized (perhaps rightfully) Buick’s making the oil pump a part of the timing cover, but that’s a different subject.

But if the retainer works when it’s at the top, having one at both ends would ensure there would always be one at the top. It seems the retainer does no harm at the bottom – it’s merely ineffective.

Or perhaps I’m misunderstanding – which is not uncommon.

Oh, I see what you’re saying! Yes, that would work, but it would undoubtedly cost an extra cent per engine, and we all know how those things go.

Henry McNamara and all that … you’re absolutely right – $0.01/car x 100,000 cars is $1000 of tax-free savings.

They say incremental manufacturing costs are passed on to the consumer at 4:1.

Do you think the average backyard mechanic who drops the shaft down into the bowels of the engine wishes the original car had been marked up an additional four cents?

Maybe they were taking a page from GM’s Deadly Sins Playbook and being cheap. What, maybe a penny or two saved on each car? Paul has spoken at length about this kind of thing.

A better idea (oh wow, I just realized I dropped an unintended Ford 💡 Pun) would have been to make the shaft idiot proof in the first place, by simply making the hex a different size on each end of the shaft. Then you can only put it on one way.

But then I’m just a mechanical designer. What do I know? 😉

I can see the bean counters shooting that one down, to avoid the extra machining step. Sounds great in theory though.

Times two…including that it would be a great idea!

You make me realize that I never took a distributor out of a Ford of that era. It is hard to tell from the pictures, but is that Tinnerman nut removable? And would moving or re-fitting the nut on a shaft in the engine be only nearly impossible or actually impossible?

Every car has it’s “thing” and if we keep it long enough and do enough of our own work, we will eventually experience it. You have surely experienced more of those things than many of us here.

You can move the nut/collar, JP. I’ve never tried it, but I imagine that using the jaws of a vice to rest the collar on and a rubber hammer to gently tap the shaft itself would get the job done.

Chevy small block and big block distributors also drove the oil pump but used a slot/blade coupling to drive the oil pump. They used a plastic sleeve on the pump connection to keep everything together. Those sleeves had a bad habit of breaking when you installed them, the trick to installing them was to have two of them. The one you installed would never break if you had a back up one. You have only one, it splits every time. I had heard of many tips, soaked in hot water, lube with oil or grease, nothing seemed to work better than a squirt of oil, shaft mounted in a vise, oil pump lined up and a quick thump from a dead blow hammer.

The fun part was getting the HEI distributors installed in the correct location way the heck back there by the firewall, it would look good until it dropped down unto the oil pump driveshaft and then it was either to far forward or to far back, OK, pull it up and try again.

The nice thing about Fords is that it’s easy to get the gear/rotor lined up and then use your remote starter to bump the starter until the oil pump shaft engages with a little downward pressure. That’s a lot harder with a GM car because the starter solenoid is buried down with the starter. Couple that with, like you said, a distributor that’s back by the firewall, and you can say that Ford at least got two out of three things right.

Got that right although the Mopar 360, with distributor in the back, is pretty easy to get it given the bottom of it’s shaft. The beauty of it is that if you have the crank at top dead center and drop the distributor in you are either dead on or dead off 180. There is none of this 10-20 degrees off either direction that can easily happen on a Ford since the rotor spins as the two gears mesh when you drop it in.

Now we just need to put this out on facebook, to get The Knowledge out there!

Poka-yoke: (“PO-kah yo-KAY”): a Japanese term for mistake-proofing. It’s one of the guiding philosophies that made Japanese cars better-built, better-working, and better at staying fixed than American ones in the ’70s and ’80s. In a case like this, it would have meant designing the oil pump driveshaft such that it cannot be installed wrong way round.

Ok, a question about the 390 in the T-bird. Now I have four old Fords with a 289, 302, 390, and 410. I’m sure you are aware of the big differences between the oil pans for the small block Windsor and the big block FE. I have replaced one pan of each from under my cars. One in the Cougar and the other in the Parklane. With the flange flat all the way around on an FE it was a piece of cake to changed out the dented one for a new one. On the small block you have to deal with those seals at the front and back end for the crank. What makes the FE pan difficult under a T-bird while the Parklane was easy?

Your Cougar probably has a removable crossmember (not sure about the Park Lane), but the T-Bird has a large built-in tubular front crossmember inches below the oil pan. It will require raising the engine a bit and removing the oil pump while the pan is hanging there…not a super tough job, but a little miserable all the way around. I’ve had the oil pan off in-car in several of my cars before, and they all present various difficulties. One of the best things ever for a small-block Ford is the Fel-Pro one-piece silicone oil pan gasket that comes with little tabs to hold it on while you install the oil pan. It is SO much better than the original erector set.

Here’s a picture from the internet of the undercarriage of a T-Bird…

There is a wide cross member, much like the one in my F-100, in the Parklane but low enough to present no problem. Now after seeing yours I understand and I also understand why I will never want such a T-bird with that Rube Goldberg steering setup.

Great article Aaron. Ford oil pump driveshafts also have a reputation for being weak. When put together my Torino’s engine, I didn’t take any chances and installed an ARP driveshaft, which includes the collar.

https://www.jegs.com/i/ARP/070/154-7905/10002/-1

Thanks, Vince…I recently saw a picture of a Ford oil pump driveshaft that was twisted like a soft-serve ice cream cone. Kind of neat, unless it’s yours, although I can’t imagine that kind of thing is too common.

I had that happen to the 289 in my ’67 Mustang a long time ago. I got in the car to run an errand and noticed at the end of the block that I was showing zero oil pressure. When I replaced it I took the advice of the NAPA guy and installed an aftermarket one that was a lot stronger.

Cougars do have a removeable crossmember, two bolts and its out of the way.

“Do you think the average backyard mechanic who drops the shaft down into the bowels of the engine wishes the original car had been marked up an additional four cents?”

More often than you’d imagine…..

One of the things my son taught me was the modular construction of 80’s Hondas ~ it made them easier to assemble and so easier to take apart for routine mtce jobs like clutches, drive axles and so on…

-Nate