original junkyard photos by Jim Klein

original junkyard photos by Jim Klein

Automotive history of the 1950s is commonly reduced to an orgy of fins, chrome, V8 engines and the inexorable influence of the longer, lower wider mantra. They were heady times for the Big Three, especially GM and Ford, as they rolled up ever bigger sales, market share and profits and steamrollered the independents. But one of those independents, Nash, started the decade with a brilliant and unique vision for a different sort of American car, the Rambler, as the way to survive.

Unlike the common image as boring cars for the thrifty and practical, Rambler started out very different, with Buick-territory prices targeting an affluent demographic—particularly women. Rambler in the early-mid ’50s was the closest thing there was to a chic, upscale continental-style American “import”; the BMW of its day. That’s how it survived the onslaught of three other new compacts in the first half of the ’50s and then just barely staved off extinction from a price war by Ford and GM. It then leveraged that image—along with more affordable prices—to fight back and take on the Big Three at the end of the decade. By 1960, Rambler had increased AMC’s market share by a whopping 270%.

How Rambler pulled that off is the biggest and most unlikely automotive story of the 1950s.

Defining “Compact”:

Before we take what’s going to be a deep dive on this subject, a brief note on the terminology of “compact”. Prior to 1962, when the Ford Fairlane introduced the concept and term “mid-sized”, which then defined compacts as a specific category, the term “compact’ was used to define any car that was relatively smaller than the traditional cars (not yet called “full sized”) from the Big Three and other independents. That leaves a bit of gray area, as the traditional big cars were mostly not all that big at the beginning of the decade, but grew dramatically throughout it.

For this exercise, compacts are defined as having a maximum 110″ wheelbase. That leaves at least two somewhat smaller cars out of the discussion, which I’ll address here briefly.

The 1949-1952 Plymouth P17, P21 and P22 series had a 111″ wheelbase, and was 185″ long. It was essentially a shortened (at the rear) version of the regular 118.5″ wb Plymouth, and only accounted for some 13% of total Plymouth sales, the majority of those being the wagon (more on that later). They were a short-lived attempt at something a bit shorter, but fall outside of our criteria.

Some may suggest that the Studebaker Champion should be considered a compact, due to its relatively narrower body and lighter weight. But there’s two arguments against that: in the early ’50s, its body wasn’t all that narrow in relation to other full-size cars, and its length was always very much full size. At 197″, this ’51 Champ is the same length as a ’51 Chevy. And in the later ’50s, the same was the case: the ’55-’58 Champion was a couple of inches longer than a ’57 Chevy. Length creates the visual indication of size, and impacts maneuverability and such. And its wheelbase (112″-116.5″) was always solidly in full size territory. For what it’s worth, the smaller of Nash’s “full size” cars, the Statesman, had a 112″ (later 114″) wheelbase, but was a bit over 200″ long too.

Although the term “sub-compact” didn’t exist in their time, I’m going to use it for the Crosley (l) and the Metropolitan (r), as they’re clearly well below the size and passenger capacity of the compacts in this analysis. But they are a reflection of the interest in such a category, as they both sold in not-utterly insignificant numbers during their peak years, the Crosley attaining a 0.8% market share in 1948, thanks in good part to the post-war seller’s market.

Setting the Stage:

Before we jump into what actually transpired in the great compact war of the ’50s, we need to consider what almost happened, but didn’t. The Big Three all had various experimental small car projects going back to the 1930s, when their cars started to grow and the Depression created interest in smaller and cheaper cars. These efforts were stepped up during WW2, as there was a widespread belief among economists that the country would fall into a deep recession after the war ended, as had been the case after WW1.

This resulted in some very well developed compact cars, and in one case, a quite ambitious one, in the form of the 1947 Chevrolet Cadet (above). The brilliant engineer Earle MacPherson headed up a development team and was given wide latitude to explore the concept of what a modern American compact car could be. The result was a compact and light (2200 lbs) sedan that seated four comfortably, and some of the solutions to achieving that end were novel. It had a 133 ci (2.1L) ohv six, with the transmission under the front seat for maximum space efficiency, four wheel independent suspension via the first intended application of MacPherson’s famed struts, as well as other advanced features.

It never went into production because it was deemed to be too expensive to achieve the high internal profit goals at GM at the time (30%), and GM anticipated the very issue that occurred in 1960 with Ford’s Falcon, that the Cadet would cannibalize the full size cars, which would then hurt their profitability from reduced volumes. Why build two lines of cars when one will do, especially when one has the volume to price the lowest trim versions at unbeatable prices?

Similarly, Ford developed a compact car in during and after war, intended to go into production in 1949. But when the 1949 Ford was reduced in size from its original Mercury body, Ford also anticipated the 1960 Falcon scenario of cannibalization and pulled the plug, sending off the final version to France in the form of the Vedette. I’m not sure what engine the US version would have had, as the French version was also given the old V8-60 flathead.

Chrysler also had various experimental small car programs active at the time, as a fall-back in case either Ford or GM put theirs into production. If any one of the Big Three had put their small car into production, the other two would almost certainly have put theirs into production also, as a defensive measure. This acted as a brake, as none of them wanted to start an unwinnable compact war. If it had happened, the independents would almost certainly never have jumped into the compact segment, and the automotive landscape would have been altered very significantly. Nash/AMC almost certainly would have died along with the other independents. The Big Three’s resistance to building compacts created an opening for the independents. It turned out to be a very compact opening.

As is invariably the case, the success story behind Rambler and the survival of Nash/AMC was written by an exceptional man. George Mason was not the typical automobile industry CEO. Highly intelligent, energetic, and visionary, Mason had a keen insight into human psychology behind consumer decisions. A key protege of Walter Chrysler, Mason moved on to head up appliance maker Kelvinator, where he quadrupled profits in the depths of the Depression, and made the firm the second largest appliance maker after GM’s Frigidaire. His experience successfully selling appliances mainly to women would color many of his future decisions at Nash/Rambler.

Approached by aging founder Charles Nash to be his successor, Mason insisted he would only come if Kelvinator came along too. The subsequent merger in 1936 created Nash-Kelvinator, and by 1940 the firm was enjoying strong profits.

Mason was progressive in his thinking, and adopted new ideas and technology readily. During the war years, he and his team of engineers explored aerodynamics in a wind tunnel. The result was the aerodynamic 1949 Airflyte range of full-sized cars, the 112″ wb Statesman (top) and the 121″ wb Ambassador, commonly referred to as “bathtub” Nashes.

Mason (r) had always been intrigued by smaller cars, which would eventually lead to the two-passenger Metropolitan, the Nash-Healey sports car, and of course the Rambler.

The 1950 Rambler:

What arrived late in the 1950 model year was very different than anyone might have expected an American compact to be, certainly so what GM, Ford, and Chrysler had in mind, and as we’ll see, what Kaiser, Hudson and Willys actually built. It was not just a smaller, cheaper sedan; it was a high-content, high-style small car with a body style utterly out of the ordinary: a fixed-profile convertible dubbed “convertible landau coupe” by Nash. The fixed roof rails allowed the unibody to be very rigid, and an electric motor opened and closed the top, not unlike a modern Fiat 500 and a few others.

click on all images for max size

click on all images for max size

The Rambler came fully equipped with standard features that even Cadillacs didn’t have: whitewall tires, full wheel covers, clock and even an AM radio. Price? $1808, almost 30% more than a basic Chevy full size sedan and $5 more than a Buick Special fastback 8 cylinder coupe. Now that was different and unprecedented.

The Rambler’s target demographic was all-too obvious: style-conscious women who could afford a stylish car.

Like Lois Lane, reporter for the Daily Planet. “Superman” was my tv screen introduction to the Nash Rambler, as I don’t ever remember seeing one of these convertible landaus in Iowa City after we arrived in 1960.

What would this demographic be buying in 1960? A Karmann Ghia or Corvair. And in 1965? Mustangs, of course. And in 1980? A VW Cabriolet or a BMW 320i. George Mason was way ahead of his time, and playing the long game. He rightfully anticipated that the Big Three would crush the independents’ big cars through their huge volume and pricing, so he was positioning Rambler in a niche of its own, along with some of the early imports. Establishing the right public perception was more important than volume; that could and would come later. It’s the same playbook used by almost every successful new premium-brand introduced in the US; mostly imports, of course.

The convertible landau was just the opening act.

Quite late in the 1950 MY, a cute little wagon appeared, being admired once again by only women. And yes, that body style was almost as radical as the convertible landau. It’s easy to forget, but before WW2, essentially nobody bought station wagons for personal use; they were expensive, built out of maintenance-intensive wood, and were bought for commercial use or for ferrying guests at a rich man’s hunting lodge or country house.

Willys broke the mold with their all-steel 1946 wagon (with faux wood-grain paint). It was the first step in domesticating the station wagon, if a bit too Jeep-like for women. The Willys Wagon essentially saved the company after the war, as its Jeepster was a sales dud.

Plymouth went one step further with their 1949 all-steel Suburban. It was on the short 111″ wheelbase, and only 185″ long, and as such can be considered a near-compact. To put it in perspective, its dimensions are almost identical to a modern Toyota RAV4; no wonder the Plymouth wagon was a hit with women and young families: compact, easy to drive, and plenty of room for kids and whatever needed hauling.

The Rambler wagon was something totally new again: the first lifestyle wagon ever; the Audi Avant of 1950. Like the convertible landau, it was equally-well equipped and priced at the same $1808 in 1950, but both had a substantial increase in price for 1951: $1993. America’s first premium compacts.

The Rambler wagon was something totally new again: the first lifestyle wagon ever; the Audi Avant of 1950. Like the convertible landau, it was equally-well equipped and priced at the same $1808 in 1950, but both had a substantial increase in price for 1951: $1993. America’s first premium compacts.

1951 brought the third addition to the Rambler line: a hardtop coupe. Still no sedan! Hardtop coupes were the hot new thing, having been pioneered by GM just two years earlier. Rambler beat Ford and the other independents in the hardtop race.

It’s easy to dismiss these little Ramblers from a modern perspective as dumpy and silly little cars, but that would be missing what was the most important story of the early 1950s. They were bold and stylish at the time, and the choice to start with these three highly unusual body styles was radical and unprecedented.

A key part of making the Rambler appealing to fashion-conscious women was that its interior fabrics and trim were designed by the renowned Helene Rother, who had been GM’s first woman interior designer back in 1943. A woman’s touch can’t be easily faked.

Let’s take a closer look at the technical aspects of these initial Ramblers, as they largely formed the basis of every Rambler to come until 1963/1964. Nash was a pioneer in unitized body construction (unibody) having switched to that back in 1941. This alone was technically advanced and almost unique in the US at the time, along with Hudson. It created a strong, stiff structure, which contributed to the Rambler’s feeling of solidity and more worthy of a premium price, especially compared to the oft-willowy BOF cars from other manufacturers.

The Rambler’s front suspension was similar to that used on the large Nashes, with long coil springs seated above the upper control arms. Ford (and others) would adopt this with their 1960 Falcon, and use it for two decades. Although the trunnions that were necessary in that pre-ball joint era later got a bit of a bad rep, it was also a very advanced design at the time, offering a good ride as well as decent handling.

The following description of this system (and related issues and repairs) is from this site, which describes more detail and rebuilding:.

This is a double wishbone and trunnion system, with the road spring directly over the steering knuckle, in line with the virtual kingpin. This design has wonderful control over understeer in turns, and an anti-roll bar is unneeded (and not available). The spring carries load directly, not multiplied by moment (distance from fulcrum) so the spring is softer and lighter. Spring-over-knuckle also eliminates decreasing roll resistance in turns, a characteristic of most American suspensions through the 1980’s, often compensated for by anti-roll bars. The downside of the spring-over-knuckle system is that it is very tall — this really limited AMC’s styling choices until the adoption of the new system in 1970.

The upper control arm trunnion system fails more often than not. The head of the trunnion pivot bolt is supposed to “jam” on the leading arm, and a nut and lock washer jams the bolt to the arm on the other (at pink Y). This does not survive ordinary use patterns.

The bolt is supposed to rigidly connect the arm halves, and pivot within the casting. What usually happens is that given the large contact area the bolt freezes in the casting. This forces the bolt to rotate in each arm half, stripping the threading in the thin, stamped arms. No longer a stiff A-arm, all of the components shift around in operation, ruining the arms.

The rear suspension was a typical Hotchkiss set-up, with a live axle suspended on semi-elliptic leaf springs. This would be used on the 100″ wb Ramblers until their end in 1964, and on the 1954-1955 108″ wb Ramblers before being replaced by a coil spring and torque tube drive design in 1956.

The Rambler’s flathead six displaced 172.6 ci, and was rated at 82 (gross) hp. This small Nash six dates back to the semi-compact Nash 600 from 1941. Weighing 2430 lbs, the Rambler had a favorable power-to-weight ratio for the times, and was deemed to be relatively nimble. A test by the British Magazine Motor yielded a 0-60 time of 21 seconds, which was quite typical of the times, and a top speed of 81 mph. Fuel economy was 25 mpg. Overdrive was optional, and Ramblers quickly established a reputation for good mileage; 30 mpg was possible with a light foot. Handling, steering and braking were all deemed to be good to very good.

As is quite obvious, the engine is a rather wedged in between the massive inner fender bulges, due to the narrow track of the front wheels (52.25″), in order to provide adequate movement for them inside the covered outer fenders. The turning circle was 37 feet, not superb but not bad considering the design of the skirted fenders.

The Rambler had a stylishly simple instrument panel—not unlike the recent Fiat 500—which reinforced its image. The column shifter was nicely enclosed unlike most at the time, and the single round combo instrument was easy to read. It had a decidedly European air, as did much of the car. Nash’s vastly superior integrated heating and ventilation system only enhanced the positive qualities further.

The Rambler was billed as a five passenger car; three in the front and two in the back, where the wheel wells intruded into the seat cushion. Its exterior width was fairly ample at 73.5″, thanks to its bathtub styling. Interior width was of course not quite up to the bigger cars, but at 56.2″ inches at the front (hip and shoulder room) it was just a hair less than the 1960 Falcon would have.

We’ll get to some detailed sales analysis with charts a later, but sales for an abbreviated 1950 totaled 11k and 69k in 1951. But here’s the most significant number: 50% of those were for the wagon. That is utterly unprecedented; as a point of comparison, the popular Plymouth all-steel wagon represented all of 6% of 1950 Plymouth sales and at Chevrolet, wagons were 2% of the total. Although those percentages would not quite hold up, Rambler would go on to consistently have much higher share of its sales be wagons than any other manufacturer.

Despite the addition of two and four door sedans in 1955, that year Rambler wagons’ share of sales increased further, to 55%. And in 1959, it was still at 44%.

As a point of comparison, wagons made up 9% of Chevrolet’s sales in 1955, and 17% in 1959. It was slightly higher at 19% for Ford in 1959. Rambler had staked a claim to compact wagons, and held it. It became a key aspect of their image, which continued to resonate with a key demographic; buyers who eschewed excessive size and poor space utilization for the inherent advantages of a wagon. They really were the Volvo wagon of its time.

Henry J:

Rambler only had the compact field to itself for part of a year, if we exclude the tiny and cheap Crosley. The Crosley represented a fundamental lesson that Henry Kaiser had not yet learned, and is still relevant today: American would rather buy a used car than a cheap new one. Henry Kaiser had always wanted to build a really cheap, small car, but circumstances (which we covered in Part 1 of our Kaiser-Frazer history) didn’t make that possible, at least not in the first few years.

Henry’s ego and drive were never to be denied, and so he plowed what little resources K-F still had into developing the Henry J compact. The other alternative would have been to bring David Potter’s 288 ci prototype V8 engine to fruition and production. There’s no doubt that would have been the wiser of the two options, as the big Kaiser was stuck with the increasingly obsolete Continental 226 flathead six. A modern, powerful V8 would have made the new 1951 Kaiser cars something truly exceptional, given their low stance and otherwise superior dynamics.

Contrary to common myth, the new V8 David Potter went on to design for Nash/AMC a few years later had little or no resemblance to that Kaiser V8 (above), but he took advantage from what he had learned quite effectively.

The 1951 Henry J was almost the perfect antithesis to the Rambler. It was built to a low price; $1363 for the four cylinder; $1499 for the slightly better-trimmed six cylinder DeLuxe. Cheap is of course relative: a 1951 Chevrolet could be had for $1540. The four was the Willys “Go-Devil” 134 ci flathead with 68 hp, and the six was the small Willys 161 ci flathead, with 80 hp. The six with the relatively light (2,341 lbs) HJ had better than average acceleration, but that was the extent of its assets. Corners were cut everywhere except in its tail for a trunk opening or the dash for a glove box. As to its looks, it certainly wasn’t very stylish, inside or out: A poverty-mobile.

The Henry J had a decent first year, with 82 k sales, a bit more than the Rambler. But that dropped by 63% in 1952, and by some 50% in 1953. About two thousand more were sold through Sears as the Allstate. By 1954 it was all over, the first of the new compacts to go belly-up. And the huge losses and sunk investment of the Henry J program essentially pushed Kaiser over the edge, resulting in a merger with Willys, so as to be able to consolidate its rapidly decreasing production in Toledo and escape its mega-factory at Willow Run.

Hudson Jet:

The next contender in the compact wars was already waiting in the wings. Hudson too saw that Mason’s logic made sense, that big cars were an endangered species in the gunsights of the Big Three, and so decided to build its own “Rambler”. The result was the 1953 Hudson Jet. But unlike the new Boeing jets of the time, the Hudson Jet flamed out and never took off.

With a 105″ wheelbase and a 104 hp 202 ci six—essentially three-quarters of the old Commodore inline eight—the Jet was clearly positioned higher than the Henry J, and the Rambler too, in terms of its size and power. It also weighed more (2700 lbs), and in the Hudson tradition, was solidly built with a unibody structure and had good road manners. In its numbers, it looked to have potential.

But the Jet had a fatal flaw, in that its proportions and styling were just plain dumpy. This was not the fault of Hudson’s excellent chief designer Frank Spring; company president A.E. Barit insisted on…this instead. Why pay designers, if you can do it yourself?

The Jet’s starting prices were between $1858 and $1933, about the same as the Rambler. But it utterly lacked the Rambler’s pizazz, came only in stodgy two and four door sedans, and did not include all of the standard equipment that Ramblers had. As a point of comparison, a 1953 Chevy started at $1613; given the volume war that was full on in 1953, hefty discounts were readily available.

The Jet’s timing was terrible, as 1953 marked the huge battle instigated by Ford for volume and share, and one which Chevrolet was not going to lose. The losers were everyone else, most of all the independents. The Jet sold all of 21k units in 1953 and 14k in 1954. And like at Kaiser, the investment and losses from the Jet program essentially killed Hudson, forcing it into a merger with Nash, thus creating American Motors, Mason’s first step in his long-hoped for merger of all the independents. But all Nash really got out of the merger was access to Hudson’s dealer network, and the elimination of a competitor, as Hudson soldiered on through 1957 with badge-engineered big Nashes.

Willys Aero:

One year after the Jet showed up but didn’t take off, Willys’ launched their ambitious new compact, the Aero. With an even bigger 108″ wheelbase, the Aero, right down to its Falcon name, was the closest preview of what Ford would launch in 1960. Willys was no stranger to compacts; in fact that’s all they had ever built since about 1933, starting with their quite advanced “77” in that year, which spawned a line of compacts right up until the start of the war. The pre-war Willys were the precursors to the compacts to come.

The Aero came in several trim levels, and prices started at $1731 for the Aero-Lark, with the 75 hp flathead 161 ci six, and up to $2155 for the fairly nicely trimmed Eagle hardtop coupe, with an F-head version of the 161 ci six, making 90 hp. And there was an Aero-Falcon in between. And where did Studebaker and Ford get the names for their compacts?

The Aero was clearly more modern than the other three compacts in terms of its styling and proportions. A fine looking car at that. It was also bigger, and most of all, wider. Its performance, especially with the optional big 226 Kaiser six available in ’54 and ’55 (thanks to the merger of Kaiser and Willys), ranged from good to excellent. Its handling and general demeanor was very good. It really deserved a better fate than to be killed off after four lackluster years, selling only 42k in the best of them (1953), and that’s with lots of heavy discounting. It too was devoured in the maw of the 1953 battle of Ford vs. Chevy. At least it had a long and happy life in Brazil, where it was truly appreciated.

The Rambler, year-by-year: 1953

It’s not like Rambler managed to escape significant impact from that sales war in 1953. Sales had already dropped a bit in 1952, down to 52k from 69k in ’51. All things considered, that was pretty good, given that there were now three other compacts, all hungry to survive. The compact war was now on too. Rambler showed up for the 1953 fight with new designer duds, attributed to no less than the renowned Italian designer Pinin Farina.

Mason had contracted with Farina to design a prototype for the completely new 1952 line senior Nash line (above). There’s no photo of what he submitted, and Nash chief stylist Ed Anderson had already developed one too. In the end, it was largely Anderson’s car, but a number of Farina’s elements were incorporated, such as the shape, size and texture of the grille, clearly a Farina hallmark. Since the Pinin Farina name was just becoming known in the US, Mason wisely made full use of it.

The ’53 Rambler’s front end was Farina-ized, with a more squared off look, and the windshield was enlarged. If Anderson and Farina had their way, the front wheels would have come out of hiding, but that would have to wait for two more years. GM’s Hydramatic was also optional starting in 1953, and a bigger 195.6 ci version of the six, rated at 90 hp was teamed up with it. Even then, this was likely the lowest power engine teamed up with the Hydramatic. It was actually a good choice, as it was a very efficient automatic, and its four gears made the most of the little “Flying Scots” six.

1953 was a bad year, and Rambler sales dropped again, by almost 40%, to 32k. More ominously, total Nash market share plummeted almost by half, to just 2%. Mason’s gamble was starting to look questionable. Studebaker took a similar sized hit in ’53, one from which it would never really fully recover. Hudson too lost half its market share, now down to a mere 1.1%, and cried “uncle” the following year. Willys would survive thanks to the merger with Kaiser, but things would be shaky there for some time too.

1954 Rambler:

But Nash wasn’t backing down; instead, it upped the ante, with a new dual-pronged strategy. The Rambler line would be expanded, with new four door sedans and station wagons, on a longer 108″ wheelbase. This made the Rambler a nominal six-passenger car, and more directly competitive against the Big Three. And in order to do that, prices were slashed across the line, a quite radical (or desperate) move. The sedan was available at the beginning of the model year; the wagon later.

Yes, Rambler was in love with continental spares, and offered them as a relatively popular option.

A basic two door “club sedan” was also added, its price a mere $1550, undercutting the $1680 base price of a Chevy. Of course this new base “DeLuxe” trim didn’t live quite up to its name. The Customs also had their prices reduced some 10%, but whitewalls were now optional.

As noted, the four-door wagon, dubbed “Cross Country”, arrived later in the ’54 MY. The design by Bill Reddig allowed the use of the same dies to produce door framing for sedans and station wagons, while the dip in the rear portion of the roof included a roof rack as standard equipment to reduce the visual effect of the wagon’s lowered roofline. This would become a hallmark of all four-door Rambler wagons until 1963/1964. More on that when we get to our featured ’55 wagon shortly.

Nash had always been a pioneer in heating and ventilation, and in 1954, the Rambler became the first regular production car to have a fully integrated air conditioning under the hood. This was a huge breakthrough, and allowed Rambler to offer a/c for half the price than it cost on other makes.

Rambler’s originally strategy was successful in establishing the brand’s positioning, but it now needed to be broadened via more mainstream body styles and a lower entry point. Sales increased, by a modest 13%, and market share increased from 0.5 to 0.7%. 1954 was the turning point, even if genuine success was still several years off.

1955 Rambler:

There was just one big change for Rambler in 1955: the front wheels finally grew up and stopped hiding behind the fixed front fender skirts. Why? Here’s the story as commonly told, and in this case from Wikipedia:

The Nash Rambler’s most significant change for the 1955 model year was opening the front wheel wells resulting in a 6-foot (2 m) decrease in the turn-circle diameter from previous year’s versions, with the two-door models having the smallest in the industry at 36 ft (11 m). The “traditional” Nash fixed fender skirts were removed and the front track (the distance between the center points of the wheels on the axle as they come in contact with the road) was increased to be even greater than was the Rambler’s rear tread.

Designers Edmund Anderson, Pinin Farina, and Meade Moore did not like the design element that was insisted by George Mason, so soon as Mason died, “Anderson hastily redesigned the front fenders.”

The quote “Anderson hastily redesigned the front fenders.” (and citation) is from ateupwithmotor’s article on the Rambler. But as is the case with a number of automotive legends and myths, like the “garden party” story about the 1962 Dodge/Plymouth downsizing, there’s a bit of a timing and logic issue with this one that no one seems to have considered until now. George Mason died unexpectedly on October 8, 1954 from an acute illness. And the new 1955 Ramblers, with exposed front wheels and a wider front track, were shown to the public on…

…November 23, 1954. Sorry, historians, but there’s no way that the front fenders were redesigned and tooled up, the front suspension track widened, the steering gear ratio changed, new low friction bushings in the revised gear/linkage tooled up, etc., all in time for the new ’55s to be shown at the dealers only 46 days later, with PR materials, brochures printed, and photos shipped in advance. The automobile industry just doesn’t work that way.

It’s time to put that story out to pasture, along with the December garden party.

Let’s take a good look at this superb junkyard find by Jim Klein. Ramblers from before 1958 are exceedingly rare, unless perhaps at a car show in Kenosha or such. But then that was the case back in the day, as their low production volumes attest. I have zero conscious memory of ever seeing one of these ’54-’55 four door Rambler sedans or wagons. And that goes pretty much for all of the early Ramblers. Undoubtedly there were some around, but I simply cannot conjure up any that left a lasting impression from my days in Iowa City (1960-1965). Yes, there were scads of ’58’s and newer, mostly wagons (like the green one next to this one), including at least two owned by family friends, and I’ve written up my memories of riding in them here. But none of these early Ramblers.

It’s impossible to know whether this Cross Country was sold originally as a Nash or Hudson, as the round badge on the center of the grille that would identify that in previous years was deleted for 1955, although some pictures still show it.

Jim was very thorough, and shot the manufacturer’s plate, which identifies it as simply a product of American Motors, with no reference to Nash or Hudson, who were just the dealer groups that sold the Rambler. That makes sense, as that way the cars could be directed to whichever dealer group required it. I’ve consolidated both brands in my stats and charts (last part below), but as a frame of reference, in 1955, the breakout between Nash and Hudson was 69% to 31% respectively.

For what it’s worth, this one has a junkyard marking on its fender that says “55-56 Hudson”. That’s wrong on two counts: the ’56 was a totally new car, and there was, to the best of my knowledge, no way for them to know it was a Hudson, unless perhaps the seller told them so, or there was some other paperwork identifying it as such.

What we do know is that this was a Rambler Custom Cross Country, the most expensive in the ’55 line-up, at $2,098, or $44 less than a ’55 Chevy 210 4-door wagon. Somewhat curiously, there was no DeLuxe, but there was a low trim model designated “Fleet Cross Country”, along with a Fleet utility two-door wagon and business sedan, targeted at commercial users.

This wagon is relatively intact. Here’s your chance, Rambler lovers.

Plenty of patina, but no obvious terminal cancer.

I’m guessing that’s the gas tank in there, but I never assume anything in junkyards.

Let’s take a look inside.

Aha! Nash’s famous reclining seats that folded down into a bed finally made their way into the Rambler line, as the 108″ wb sedan and wagon were now long enough to accommodate them.

The original Rambler instrument panel is still mostly there, although it got an inset panel on the passenger side a year or two earlier.

It was starting to look a wee bit out of date. Fashion changed quickly between 1950 and 1955. The glove box is a slide-out tray.

I love that combo instrument; reminds me of my VWs, and it’s a lot like the one in my xB. Who really needs anything more? Given the lack of a quadrant, I will assume that this is a manual transmission car, and not sporting the Hydramatic. By the way, I have a Motor Life vintage review of a wagon just like this with the Hydramatic. And in case you’re wondering just how slow a 90 hp 4-door station wagon with automatic and air conditioning was, it took 23.5 seconds to amble from 0-60. Before you laugh, that was still reasonable in 1955, for a car that obviously had no sporting ambitions. Or did it?

On Motor Life’s slalom course, it beat the best previous time of any car they had tested by two seconds! The typical big American car took 20 seconds; the best they had previously tested was 16 seconds; the Rambler wagon made it through in only 14 seconds. They tested it in part because of the new quicker and revised steering for 1955, which was deemed “quick, but hard”. So much for Rambler stereotypes.

As a frame of reference, that 0-60 time was exactly the same as that of a 1975 Ford Granada with the 250 six.

Looks like gold-colored anodized aluminum.

It may be my imagination, but did that increase in track also result in somewhat smaller inner fenders? The engine doesn’t look quite as jammed in there as the shot of the ’50 I showed back a ways. Of course this one is missing its air cleaner and the radiator.

195.6 cubic inches of 1930s technology, including a bore of 3.13″ and stroke of 4.25″. This venerable little mill would become the very last flathead sold in the US, all the way through 1965, in the otherwise mostly-new American.

Last but certainly not least is the Farina badge. It was a selling point, and undoubtedly Farina’s influence was to be seen, but just exactly what is lost to the sands of time. Ed Anderson took those secrets to his grave.

For a bit of reference, here’s how it looked when new. With women, once again.

And in the brochure, more women.

But here’s a handy man when you need one, to load the luggage up on the rack, so the little ones can have the way-back as their mobile playpen.

Here’s how this one could look if someone rescues it from the junkyard and spends a fortune on it. Why do I find this so oddly compelling?

1955 was a crucial year for Rambler and AMC, as Rambler sales surged 225%, and market share topped 1%. Good thing too, as big Nash sales continued their decline and the Rambler outsold the big cars 2:1. Mason’s original gamble was paying off, at least in terms of squeaking by so far, as overall Nash/Rambler market share (1.6%) was still well below the 3+% it had in ’51 and ’52.

At least the other compacts were all dead by 1955, so Rambler now essentially had the market all by itself. Well, not really, as import sales were surging, hitting almost 1% market share in 1955, but that was just the take-off point for a meteoric rise in the coming four years, propelled by VW, Renault, and a huge raft of others.

The rise of the imports created a new challenge for Rambler, as it could no longer so readily position itself as an “American Import”. It had to increasingly take on the Big Three directly, but in a more compact way. Meanwhile, it had to stomach a $7 million loss. For a well-run company that Nash had been, this was painful, but more hurt was on the way.

1956 Rambler:

After Mason died in the fall of 1954, his protege George Romney took over as CEO of American Motors. We should point out that Romney was very much involved in the creation and execution of the Rambler from the get-go, and now he was alone in the driver’s seat. As such, the new 1956 Ramblers were very much his doing, although of course their development had started before Mason’s death. The ’56s were originally intended to be ’57s, but Romney pushed up their introduction by a year. And unlike when Chrysler did that in 1957, there are no indications that quality suffered.

Romney was eager to have Rambler take the next step from a relatively niche premium-compact to a mainstream brand with compact dimensions to differentiate it from the Big Three. And although it would take a couple more years for that to come to full fruition, the timing was right. 1956 marked the ascendancy of Rambler thanks to an (almost) all-new Rambler.

Just exactly how “all-new” the 1956 Rambler is subject to debate or interpretation. Obviously it wasn’t a clean-sheet car, as AMC didn’t have the money for that, never mind the reason to do so. It’s always cheaper to remodel, even extensively, than to start totally from scratch. The ’56 is a very extensive and successful “remodel”, even if very few (if any) actual body parts were re-used.

Although certain general “architectural” concepts were still driven by the 108″ wheelbase variant of the original 1950 Rambler, such as aspects of the inner unibody structure (in principle) and the front suspension, the package was also substantially improved, by widening and squaring up the rounded body. Length increased by 5″, to 191″. Exterior width was increased by just one inch, but more significantly, track was increased by 3″ in the front and 5″ in the rear, making the new Rambler look more dynamic, with its wheels more fully exposed and now closer to the edge of the body sides.

Interior dimensions were incrementally improved, and the larger windows and more vertical body sides improved the impression of space as well as visibility.

And a threesome could make themselves quite comfortable on Rambler’s legendary Twin Travel Beds.

A new dashboard design to go along with the rest of the remodel.

There was a significant change in the chassis as well as the engine. The rear suspension was now a coil-suspended torque tube design, which improved ride materially. And the venerable Nash six was redesigned with an ohv cylinder head, upping power by 30hp, to 120.

The primary credit for styling the ’56s goes to designers Bill Reddig and Jack Garnier. Although there was no more mention of Pinin Farina, ironically, the ’56 had his direct influence all over its face, in the form of the headlights integrated within the new grille.

This distinctive front end design was first seen on the 1952 Nash-Healey, which was 100% by Farina, and in 1955 it found its way on the front of the restyled big Nashes. Now it was on the Ramblers too, although public opinion was a bit mixed. Stylistically, it was a big step forward, as it was one of the first production cars to lower its headlight from the familiar top-of-fender location. Ironically, this trend would become widespread in 1959, although with the headlights pushed out to the sides, as on the GM cars, the Edsel and the Lark. But by then the Rambler had moved its headlights back to a more conservative spot, on top of the fenders.

The four door sedan came in either a pillared sedan or hardtop, a rather bold move. Four door hardtops were very hot and new in ’56.

There’s also this PR shot of a ’56 hardtop Cross Country wagon. Unfortunately, none seem to have survived, at least in any photos on the internet.

The four door Super Cross Country was plenty flamboyant even with pillars.

The lack of fins and the more modern grille with headlights makes the ’56-’57 more visually appealing to me than the awkwardly finned ’58s. That’s not to say they were brilliantly styled; the limitations of the package and the need to use the sedan rear doors and roofline made the wagons a bit odd; the humpback look works better for me on the rounded ’54-’55s.

One of the more questionable decisions by Romney was eliminating the 100″ wb 2-door Rambler entirely in 1956. That turned out to be a mistake, as they were brought back in 1958. But undoubtedly they could have continued to add some incremental volume in 1956 and 1957. Sure enough, despite the new ’56 four doors, they only sold marginally better than the previous 108″ wb cars, and the loss of the 100″ 2-doors resulted in a significant drop for total Rambler sales, from 81k to 67k. In retrospect, that was an obvious mistake.

Losses piled up, to the tune of $20 million.

1957 Rambler:

The big news for 1957 was V8 power. The engine that David Potter had been developing for AMC was finished, and arrived in two displacement variants: 250 ci (4.2 L), and 327 ci (5.4 L), with the 327 intended for use in the final-year large Nash and Hudson, to replace the purchased Packard V8. In the Rambler, the 250 V8 was rated at 190 hp, and made it a solid performer. But the majority of Ramblers continued to be sixes.

The standard six was uprated to 125 hp, and there was also a “power pack” version with a two barrel carb that was rated at 135 hp.

Rambler was ahead of the times in a number of ways, but sometimes too much so, as in their ill-fated foray to create a compact muscle car in 1957. By dropping in the 327 V8 and beefing up the suspension, the 1957 Rebel was genuinely fast. AMC’s original plan called for it to be fitted with the ill-fated Bendix Electrojector FI system to produce 288 hp; unfortunately, the Electrojector was not ready for prime time, and the idea was scrapped. Nevertheless, the four-barrel production engine produced 255 hp, a figure that provided the 3,355-lb. Rebel with sparkling acceleration. At the 1957 Daytona Speed Week trials, a Rebel posted a 0-60 time of 7.2 seconds–versus 7.0 seconds for the top-rated ’57 Corvette. That was seriously fast in 1957.

Sales totaled just 1,500 units, most likely due to a low-volume/high-price strategy that priced the high-line, fully-equipped Rebel at $2,786–in other words, squarely in Buick territory. Rambler once could sell little six cylinder convertible landaus priced in Buick territory, but no more. Ramblers were clearly becoming primarily a compact alternative to the low priced three, and mostly as six cylinders.

1957 sales had a decent increase of 27%, to 85k and a 1.3% market share, Good thing, as big Nash sales ground to a halt, with all of 4k sold. Total AMC sales were 95k, the lowest in the post-war era. For AMC as a whole, 1957 was the nadir. If Romney’s gamble to bet the farm on compact Ramblers was going to pay off, it had to be soon, as AMC had been bleeding red ink for three years straight. Romney just barely fended off a takeover bid by the first modern corporate raider in 1957, Louis Wolfson, who intended to liquidate the company.

But thanks to an uptick in sales (and AMC’s stock price) late in 1957, Romney was able to stand firm and save the company, but it was a very close call.

1958 Rambler:

1958 would finally be the breakthrough year for Rambler and AMC. Let’s first look at the actual changes, which involved the first of several facelifts on the 108″ four doors. The front end was more traditional, which probably didn’t hurt. Fins sprouted on the back, which probably didn’t hurt either, although it was a bit questionable given Romney’s stance of going against the Big Three grain.

The Ambassador was now called a Rambler too and shared its body, except for a 9″ stretch to its front end, resulting in questionable proportions. But this had been a very long tradition at Nash, and it was a cheap way to keep a “larger” car in the lineup.

The 100″ wb 2-door Rambler was returned “by popular demand”. More like undoing a mistake, but the timing was good, as the recession of 1958 had buyers abandoning big cars like the plague. With a starting price of only $1775, the little Rambler was now the cheapest real car in America. Quite the change from how it had started out eight years earlier. And it even got rear wheel opening, although they never looked quite right. Its narrow rear track looked better covered up.

The 100″ wb 2-door Rambler was returned “by popular demand”. More like undoing a mistake, but the timing was good, as the recession of 1958 had buyers abandoning big cars like the plague. With a starting price of only $1775, the little Rambler was now the cheapest real car in America. Quite the change from how it had started out eight years earlier. And it even got rear wheel opening, although they never looked quite right. Its narrow rear track looked better covered up.

Rambler sales exploded by 75% in 1958, and AMC’s market share shot up to 3.5%, the highest since 1952. And most importantly, profits returned after a three year drought, to the tune of $26 million. Romney’s bacon was saved. Was it just the recession, though?

As I pointed out in considerable detail in “Who Killed The Big American Car?”, the recession was more like the straw that broke the camel’s back. The underlying issue was that the Big Three’s cars were getting bigger, and bigger…and bigger. And a whole lot of consumers, most of all women, were not happy about it.

Cars like the popular Plymouth Suburban (’49 top, ’57 bottom) had become huge, growing over two feet in length. Yet its interior dimensions did not keep pace, especially in seating comfort, as passengers were now squeezed between the much lower roof but the still high floor due to its massive frame. The resistance had already started in 1957, when full size cars lost 3.5 percentage points of market share. Although it had grown some, the Rambler’s size was now right in the sweet spot: bigger than the imports, but substantially shorter than the big cars coming from the Big Three.

Full size cars’ market share tumbled to 84.8% in 1958, and then again to 81.9% in 1959. The bloom was off on the big car, to stay, and not just because of the recession. By 1960, thanks to the Big Three’s new compacts, market share would drop below 70% and by 1962, below 60%. And then continue on their long death march to oblivion.

Rambler’s huge success in 1958 forced the Big Three’s hands: they each committed to their long-simmering compact car projects. Their strategy of selling captive imports was just not going to be adequate to stem the growing demand for compacts. And of course Studebaker plunged in with an extremely rushed job of hacking down their moribund cars into the compact Lark.

1959 Rambler:

There were no really significant changes for 1959. George Romney was in the spotlight now, with a cover story in Time magazine, where his deep faith, clean-living and hard-working virtues were extolled. The really big story was Rambler’s explosives sales, which were up 212%, to 374k, with a 6% share of the market. Profits swelled to over $60 million. AMC shares were red hot. Production struggled to meet demand, and the company spent considerably to expand production capacity to some 450k annually.

Good thing, as 1960 would bring more of the same, with sales topping 459k, which would only be topped in 1962, with 462k. AMC’s market share of 7% in 1959 would remain its peak. Did Romney decide to leave AMC in 1962 to run for governor of Michigan after a 24 hour fast and prayer session because he received a divine message that AMC would never do this well again? We’ll never know, but the old expression of quitting when you’re at the top never applied better.

Charts and analysis:

In this first chart we look at the domestic compacts’ market share, to visually see the compact war that played out during the decade. It’s interesting to note that each of the Rambler’s competitors had a successively weaker start before flaming out. The Rambler’s early peak was the longest (1951-1952), before weakening in the brutal market of 1953. Once the other compacts were effectively eliminated, Rambler found a new market share plateau, (1954-1957), but it wasn’t until 1958 that its share became significant and profitable. The Lark’s excellent first year had no impact on explosive Rambler share in 1959.

Here we chart the various lines of Nash and Rambler, to see the respective impacts on Nash/AMC’s total market share (red). We can see that the Rambler contributed to a rise in overall share during 1950-1952, as the senior Nash lines (green) still held a steady market share. But their terminal decline starting in 1953 combined with Rambler’s drop precipitated an existential crisis at Nash/AMC. A 1.5% market share was simply not enough to sustain the company, even though it was undoubtedly the best managed of the independents, with a low break-even point.

The Metropolitan (built in Great Britain by Austin to AMC’s specifications) contributed a steady but modest sales stream. It proved there was a market for a subcompact, but too small of one to justify domestic production. And although the share of the 100″ wb two-door Ramblers had fallen, maintaining it during the difficult years of 1956 and 1957 seems like a no-brainer.

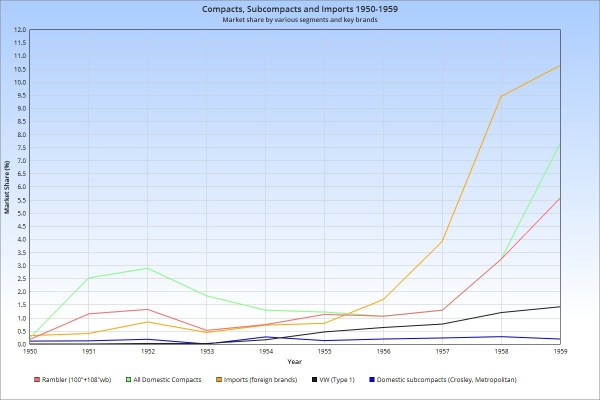

This last chart tracks the respective market shares of the key new players in the market during the 1950s: Rambler, all domestic compacts, imports (foreign brand), VW (Type 1 Beetle), and domestic subcompacts. The key takeaway is the how in 1955 imports first surpassed domestic compacts, and soared to a 10.6% share of the market. That would take a tumble in the subsequent two years, as the Big Three unleashed a barrage of compacts, but it soon recovered and by 1967 exceeded 11%. The rest is history.

As is the story of Rambler and AMC, which was the only independent to survive. And although it was 49% owned by Renault for some years and then bought by Chrysler in 1987 for $1.5 billion for AMC ($3.5 billion adjusted), it never went bankrupt (or was absorbed) like the other independents. It took the vision of George Mason and the tenacity of George Romney to see it through the wars of the 1950s, and lived to fight other battles.

A companion piece on George Romney and his years at Nash/Rambler (1947-1962) is here, and recommended as a follow-up to this article.

Related reading:

CC 1959 Rambler Classic Six: The Prophet PN

CC 1957 Metropolitan: Toy Cars Are For Kids PN

CC 1950 Nash Statesman Airflyte T.Klockau

Another excellent piece Paul. 🙂

The 1959 picture of Romney in front of what seems to be the AMC hq got me wondering about its location.

While Kenosha was always the home of Nash, it turns out that Kelvinator was based in Detroit, and after the merger the Nash offices moved into the Kelvinator factory as well.

It became the AMC headquarters until the early ’70s when they built a tower in the suburbs. I remember it as a landmark on trips to Detroit when I was young.

The old Kelvinator facility remained in use by the engineering department all the way until 2009 when Chrysler moved the last employees out.

Great article. The junkyard pictures show a detail I hadn’t seen before. The Rambler shared Nash’s unique turn signal lever, with the handle doing the flashing; and it was pivoted from the dashboard like the shift lever.

I suspect the wheels were finally opened in ’55 as a way to halfway Hudsonify the Rambler, to make it acceptable to non-Nash loyalists.

One quibble: The Wayfarer had its own two-door sedan, which was a cute bobtail unlike the Plymouth fastback. The bobtail has turned out to be the most collectible in recent years.

I’ve decided to delete the Wayfarer, as it was 195″ long. That was full-sized length at the time.

Great writeup, as usual. But I think the engine in the Willys Aero Eagle was an F-head, not a full OHV.

Yes

Oops; fixed now.

If that’s the only mistake, I’ll be surprised.

Americans weren’t very worried about fuel economy or good handling in the early 50’s, Buick was number three in the sales race.

I disagree, about fuel economy. Gas cost $0.27 in 1952, which is $2.67 adjusted. Real adjusted purchasing power was substantially lower then. Car ownership costs were considerably higher then than now. And fuel cost was a real factor in that.

That’s why more efficient cars were always bragging about their fuel economy in ads, and why the Mobil Fuel Economy Runs were a big media/PR event.

Sure, there were more affluent folks for whom it didn’t matter. But for the average worker, fuel cost was a real issue.

People drove much less back then, which is one reason fuel economy wasn’t an even bigger issue. If they had the long commutes of today, and ferried their kids around to school and after school events, it would have been a more serious financial impact.

On an inflation-adjusted basis, gas went down in price slowly (on average) during the 50s and ’60s. The low point was in the late 60s. By that time real adjusted incomes were also much higher, so cars with bigger engines and less economy were not as much of a factor as they had been in the 50s.

As to handling, it was a factor too, just not so much as we think of it. Without power steering, how easily cars steered and handled in every day driving was a very real issue, especially for women. Which was a major reason they preferred cars that were more compact, since they were the ones likely to be parking at the store and at school and such.

An often overlooked expense was the short life expectancy of the average automobile. Many US made cars required major mechanical repairs starting about 60,000 miles. It was typical for cars to need a valve overhaul and “de-coking” of the valve stems about then. Except for the more expensive cars, it was common to see engine overhauls starting around 75,000 miles.

Technology and manufacturing limitations meant small but crucial mechanical items [like tapered & roller bearings & oil seals], began failing, and don’t forget that brake overhauls typically happened every 30,000 miles. Most manufacturers specified regular engine oil changes and chassis lubrication schedules at 1,000 miles.

There has been much written about car manufacturers creating “Planned obsolescence”, making it necessary to trade in the family car every few years. But the truth is that people who could afford to do so, often traded in or sold their cars, prior to having to spend additional money on a rapidly depreciating asset.

However this began to change after the post-war sales boom receded, as families were keeping their primary car longer and buying a second car. That second car was typically a smaller car. This is one of the reasons cars like Rambler did well at first. It’s also why Rambler wagon sales were higher than the big 3. Suburbanites were discovering the benefits of having a wagon as their second car, at the same general time the costs of wagons was dropping.

My father often told me that car ownership in the 1950’s was much more expensive than in the 1990’s, when he passed. His own car selections were totally in line with rising incomes. Car loans here in Canada were rarely more than three years, so buying a new car was quite an achievement for many.

The Dodge Wayfarer was also offered as a two-door sedan. We had ours from 1950 until 1957. As for the Rambler, my aunt and uncle bought one in its reiteration in 1958. My brother, who was old enough to drive at the time, loved the car for its handling. The interior was spartan but the car was comfortable, until the day that six of use sat in the six-passenger vehicle and proved it to be not fit for the advertised passenger capacity. But the car still drove well with the load.

It’s beyond the scope of the article but the 100″ wb Rambler’s overall width decreased from 73″ to 70″ when the ’61 reskin finally presented an opportunity to trim away the excess that had been needed for the skirted front wheels to turn. That must be an all-time record narrowing in less than a clean-sheet redesign. It’s a shame Farina wasn’t given the changed dimensions to work with a decade earlier.

Some sources say the basic two-door sedan had been tooled up for 1950 and dropped at the last minute, and a (very) small number were even actually built for export. As discussed earlier ( https://www.curbsideclassic.com/blog/cc-cohort/cohort-outtake-1953-canadian-nash-rambler-or-is-it-nash-rambler-canadian/ ) it appeared in Canada immediately once Korean War shortages ended rather than continuing to wait out the Ford-Chevy price war.

Yes, that Canadian two door sedan is a curious oddity. And it certainly wouldn’t have taken much to create, just one big roof stamping.

I did fail to mention steel shortages due to the Korean War influencing the early Ramblers. It no doubt added further impetus to go for a low-volume, high-content strategy.

Thanks Paul, this was a fascinating read and a bit myth-busting as well. By the time I became auto-aware in the early sixties, Ramblers were seen as dull and cheap, especially the older skirted versions which were still quite common, though often in bright yellow or aqua colors which seemed incongruous. You made an interesting analogy with the Volvo wagon. I thought of Subaru, a company which didn’t try to take on Toyota/Nissan etc head on, but instead built an innovative brand around being practical and different. It was interesting to see the numbers on Henry J sales as being higher than Willys or Hudson compacts; I remember seeing quite a few running around the Bay Area, which of course was Kaiser country. Or maybe I just noticed them, with their distinctive styling. Anyway, this post is quite the opus!

Wow, what a treasure-trove of information about this fascinating market phenomenon.

I love the charts, which really drive the point home. I don’t think I’d realized before just how interesting the timing was that the other American compacts (Henry J, etc.) flamed out just before the compact boom associated with the 1958 recession. I guess to some extent, Rambler benefited from being the last man standing at that time.

Thanks for all the effort on this piece — this was great to read, and I’m sure I’ll circle back to read it again, too.

As someone who also writes CC posts, I must assume that this must have taken hours of painstaking work! (Worth it, my opinion.)

A question not fully answered–why, even in the ’60s, were these early Ramblers almost never seen? They look like pure, appealing designs–and the small size and basic engines (easy to work on) would make them low-burden collectables. I guess no one cares about them? Or they’re not durable? The exception is the still common Metropolitan, which was not mentioned. Other low-production cars (like 55-57 T-Birds) are still regularly seen.

Ditto the other independent compacts. I’ve never seen an Aero; In the ’80s I regularly saw a Jet in the library parking lot, but that’s it. Not even abandoned in the woods. I saw my first and only Henry J at a show 15 years ago. 49-54 Chevy, Ford, Plymouth– seen plenty.

The “death of the big car” thesis: It doesn’t explain why after people saw the advantages of smaller size, big cars continued to SELL big in the 60s & 70s, even as they got BIGGER and more ridiculous/mundane, with “We’re out of ideas” styling–vaguely boxy with amorphous curves and trimmed with plastic neo-classical add-ons. The mid-80s is when the downsizing really occurred–and that was largely by government mandate.

Today, cars are smaller than the old full-size. But now we have huge trucks & SUVs dominating the road!

Henry J’s quickly became the “Chevy Monzas” of the ’60’s. A lot of them were “tubbed” to put in big slicks and had Chevy and Chrysler V8’s installed and set up for drag racing because of their small light bodies and were dirt cheap to buy in the ’60’s. I’m sure most of those were crashed or otherwise discarded.

I even remember seeing 1/25th scale model kits of Henry J drag racers on store shelves back in the day.

And that’s pretty much been a staple in the Revell lineup ever since. Every few years they bring it back. Don’t have any photos of mine though.

Correction: I forgot that you mentioned Metropolitan in the beginning.

Once the four-seat Thunderbird debuted for 1958, resale values of the two-seat models held up well. That probably encouraged their preservation. I have a Special Interest Autos issue from 1972 that compares a 1956 Thunderbird to a 1960 convertible. The article claims that the two-seat Thunderbird used for the comparison had been restored in the late 1960s.

I never saw a first-generation Rambler in real life until the 1980 Hershey Antique Automobile Club of America (AACA) fall show. I saw my first Hudson Jet and Willys Aero in the spring of 1979, when I took a field trip with a high-school teacher to a warehouse filled with worn, unrestored cars owned by a collector in the Carlisle area.

Yes, the two-seat Thunderbird was an instant classic from the day it was replaced by the four seater in 1958. Everyone who loved them knew that it was something special and not likely to ever come back.

We had a neighbor in Iowa City who had a beautifully preserved ’56 TBird, and this was in 1961 or so. The survival rate of these must be some of the highest of any car ever.

Meanwhile, old Ramblers had zero following, and were either run into the ground or cut up into restomods, which was a a bit of a fad for the early 2-door cars.

I remember seeing 1 Sears Allstate in a junkyard, it appeared to be in a penned off area to be “saved”. It was complete and looked restorable. It was the only 1 I ever saw.

Paul I find it amusing you didn’t much care for the roof profile of the Cross Country wagons. Nissan did a pretty blatant rip-off of that same roof line on an earlier generation of the Armada SUV. I understand why Rambler did it, to use the same rear doors as the sedans. Why Nissan used that design is an utter mystery.

I noticed that Armada roof dip the first time I saw the 1st gen Armada twenty years ago. You and I assume a straight, flat wagon roofline is desirable and anything else is a compromise. Imho Nissan stylists didn’t see a compromise. I suspect they incorporated the feature to appeal to baby boomers, as a retro classic touch, reminiscent of the 50s wagons of their childhood.

Excellent, well laid out! The article does provide one interesting fact after another, and many of us can relate to the shot with “Lois Lane” about to get herself into trouble so that Superman would be needed for ANOTHER rescue!!!

Thanks for a very fine look back in the rear view mirror!! 🙂 DFO

An excellent walk through the Rambler’s formative years. I think it’s fair to say that up through at least 1955 the Rambler was a niche vehicle – a niche that Mason and Nash exploited nicely. Even as lower price/trim models became available, the Rambler never took on the “cheap car” vibe that other compacts had.

I would argue that Rambler started to make the same mistake Studebaker did in 1956 – going bigger. The car really didn’t do that well in the first couple of years, but then the US Big 3 really opened up a lane for Rambler after 1956-57. Studebaker should have been able to exploit that a bit but by 1957-58 the car was clearly ancient and not that appealing, whereas the Rambler was new and fresh (or at least seen that way). Plus the 100 incher came back to serve the low and cheap end.

I think that the Champion of 1947-52 exploited a niche of its own – at a wheelbase of 112-115 it was bigger than the Rambler, but its width, weight and economy were closer to Rambler than to the low priced 3. It allowed buyers to find a happy medium between smaller size and efficiency on one hand and being “a real car” on the other. But then it got bigger and outdated and by 1956 didn’t really have anything unique to offer.

I would argue that Rambler started to make the same mistake Studebaker did in 1956 – going bigger.

Well, unlike Studebaker, the ’56 Rambler’s modest increase in size actually resulted in something useful: a bigger interior, and not just longer overhangs and fins.

And since the Big Three cars were getting so much bigger at the time, the ’56 and up Ramblers were just right-sized, in my opinion, quite suitable for growing families, and able to be competitive to the Big Three, as there was very little trade-off in interior space except for a bit of width. The packaging on these Ramblers was really quite good, by virtue of not being too low. For a 108″ wb, they were really closer to mid-sized. In fact, they have more hip/shoulder room than the ’62-’64 Fairlane and Meteor.

Paul, I mean this as the highest compliment: your writing and exposition are rapidly approaching the level of Aaron S. at Ate Up With Motor.

Thanks.

I don’t try to compare myself to Aaron, and I make it a practice not to read his articles before I write mine, as a matter of principle.

My approach is somewhat different than Aaron’s. I spend a lot of time searching for and selecting images. I’m very visually oriented, and my background in tv undoubtedly reinforced that. I find the lack of images in Aaron’s articles problematic. He often refers to obscure cars or things, and without a visual reference, its meaning or impact gets lost or diminished.

Aaron is a classic anorak/geek: his command of minutiae is superlative. I’m more of a generalist and big-picture person. I want to know how the facts and details fit into the larger context.

And I like busting myths, including several that Aaron has repeated. If something doesn’t sound logical or right to me, I will question it.

Did that bizarro Di-Noc application on the ’56 wagon make it to production?

I have to wonder if the AMC V8 would have happened at all had they realized they could probably pick up the tooling for the Packard V8 they were already using for a song by mid-1956. Instead this less-than-2-year-old engine was simply junked. Meanwhile, David Potter’s V8 actually did make it into a Kaiser, since it was used in some ’60s Jeep Wagoneers. (Kaiser switched to the Buick Dauntless V8 after that, but after AMC bought Jeep they quickly went back to using their own engines).

Presumably.

And the hardtop wagons were actually built. George Ferencz sent me these vintage classified ads for a few.

By that time (1956) the Rambler V* was undoubtedly already far along in its development. And it was a bit smaller and lighter than the Packard V8.

They were in the catalog for four years, on the 108″ wb in ’56-7 and as an Ambassador exclusive in ’58-9. I had wondered if you had been saying they may not have made it for ’56.

Yes. it’s impossible to find one with a Google Image search. And, it’s not shown in the ’56 Rambler brochure.

http://www.oldcarbrochures.com/static/NA/AMC/1956_AMC/1956_Rambler_Brochure/dirindex.html

I was more inquiring if the weird di-noc woodgrain layout made it to production not the hardtops, which at least eventually did, but I’ve never seen a picture of one with the woodgrain in the usual ’56 two-tone area.

According to the ‘Standard Catalog of Independents’ The 1956 hardtop versions were only available in the top-line Custom trim-level along with sedan versions. The production is lumped together, for the four door sedan and hardtop: 2,155, for the station wagon counterparts: 402. How few of those were hardtops, we’ll never know. Surveying the hardtop production number in subsequent years to 1960, few broke more than a few hundred units, only over a few thousand in the last years, always in the top trim series.

I only ever saw one four door hardtop in those years in spite of having a number of successful American Motors dealers within twenty-five miles here in Western New York. An elementary school teacher who lived only a mile away on a farm had a pink and white 1959 Ambassador four door hardtop. I would see it frequently as she drove home after school was out.

That di-noc treatment is wild!

What a treat on a dreary winter Monday morning (at least, here in Pennsylvania). The first-generation Ramblers had disappeared from around here by the time I was noticing cars (late 1960s). I never saw one in real life until I attended my first Antique Automobile Club of America (AACA) Hershey show in 1980.

Interesting that George Mason was smart enough to position the first Rambler as a premium small car, and didn’t try to sell the car primarily on low price. It was a small car, but not a cheap car.

I do believe, however, that Chrysler Corporation did beat the Nash Rambler in offering a hardtop. The Chrysler Newport, DeSoto Sportsman and Dodge Diplomat debuted for the 1950 model year.

Thanks. And quite right about the Chrysler hardtops. I’ve amended the text.

I’d kill to own a fully restored wagon. And that IP is a work of art.

Only period photo I’ve seen of a Willys Aero at curbside, taken early ’60s in front of the Jacob Starr House in Wilmington, Delaware:

(Click photo to rotate).

Thanks for taking the pictures and weaving the story/history around them, it turned out even better and more interesting that I ever imagined. That little wagon was (and is) such a little looker, it’s surprising there aren’t more of them around.

And the whole Nash / Hudson / Rambler / AMC intertwinedness is finally starting to come together and make a bit more sense. Rambler’s intrigue me and as with others I was much more familiar (familiar being a vast overstatement) with their later offerings and sort of equated them to more of a budget make, with this that clearly was not always so, making it ever more interesting.

A fine example of info (and image) gathering and story telling, which sets a great example for anyone contributing at CC–I’ve read it through twice already today. Terrific!

What an amazing piece of work, Paul. I have never known much about Rambler cars, since I was born just a little too late for the earlier models covered here. I did see a fin-bedecked version and I think fins don’t really work on a car this size.

Were I to buy a new car in say, 1961, it would for me be either a Rambler or a Valiant.

Growing up in Chicago, AMC products were everywhere during their heyday. Kenosha is a far northern Chicago suburb, after all. Little Rambler dealers were all around the old suburban downtowns. In Lansing Illinois, just a block off the border with Indiana, was a big filling station that was converted during this time into a dealership called Springer Rambler. It was there that I bought my first car – a used Plymouth Valiant.

Blue collar families drove Ramber wagons and they were plentiful in the subdivision I grew up in. They were the Hyundai, Nissan and Kia of that era. It wasn’t unusual for the many families in my neighborhood to have a Rambler daily driver for Mom, and an imported car for Dad. They were seen as durable rides and to this day, I have a weakness for the 1960 Rambler Classic. My dad had two of them, a 1960 and a 1962, along with many Beetles. Our neighbors had a 1960, along with a Volvo. My other next door neighbor had a 1962 along with many different kinds of VWs. Many of our neighbors were born in other European countries and migrated to Chicago after WWII. They all drove some kind of a Rambler.

These are a few of my favorite childhood memories. I’ve written about kid adventures in the “way back” of a Rambler wagon. My first overnight road trip was taken as a kid lying on my back in a Cross Country wagon, speeding around the Lake Michigan shoreline in Michigan.

Ramblers were perfect for my childhood memories. Simple, long lasting, and honest.

https://www.curbsideclassic.com/auto-biography/kid-freedom-in-a-rambler/

Vannie

As a kid, I could not have imagined a day when there wouldn’t be AMC products on every block in Northern Illinois.

I don’t have anything to add other than that was a bloody good read, Paul.

This read has been the highlight of my day! This connects and clarifies many gaps I had in my understanding of Rambler’s perception through the 50s, with the 50 being up in aspirational Buick territory and the 60 “American” of essentially the same bones being a fairly hohum entry level car I had a hard time computing, I have misconceived habit of looking at the regular Rambler of 1956 not as a slightly larger companion, forgetting it was the successor, and that the revival of the old in the American was in fact the companion. I’m not a wagon guy but I do love the wagons, both designs, and despite the Pininfarina stuff later in the run I truly think the earlier the prettier, give me those bathtub fenders any day. 🙂

The front suspension design is really interesting to me, all Ford and Chevy(with the Chevy II) really fundamentally did differently from Rambler was use upper ball joints in place of the trunnions and put the shock inside the spring, and interestingly when AMC got into Trans Am Racing in the late 60s the engineers reverse engineered the suspension of the competition Mustangs to incorporate into all of their 1970 models, including finally switching to upper ball joints

There was a Ford hardtop in 51 though, the Victoria, it was a one year wonder on the old 49-51 body

Another half-serving of cheesecake, likely promoting the climate control:

That photo may have been taken in front of the Petrifying Springs (golf course) Clubhouse, Kenosha County. Sure looks familiar; I worked at the park there several summers.

I reckon this is your best article ever Paul. Well done, and thank you for it.

Magnificent article, Paul, thank you for taking the time to write such a thorough assessment of this important automotive trend. I’ll be recommending it to others as a standard read for understanding of the period.

Regarding the 100″ wb Rambler deletion from the 1956-’57 offering, some possible reasons to consider:

First might simply have been some body dies were wearing out, which needed replacement to continue production.

Second was volumes for the two door models had flatten after the 108″ models arrived. Adding the number arrives at approximately 15,000 annually, though that includes some Country Club hardtops and convertible landaus.

Third would be fears they might divert attention and sales from their all-new ’56 Ramblers on which all their hopes were invested.

Fourth was AMC was so financially strapped they could only afford the overhead to produce the new Ramblers while still carrying the faltering Nashes and Hudsons which they had dealer contracts to fulfill. Those were a precarious years for AMC’s survival.

Or. Maybe none of the above…

Thanks.

I’d go with number three. Presumably they wanted to only show/sell the fresh new faces for ’56; putting all their eggs in the 108″ basket. And prices were higher accordingly: A DeLuxe 4 door sedan cost $1695 in ’55; $1829 in ’56. And they had no more cheap $1585 two doors in ’56. They were trying to move back up in pricing with the new cars.

They still sold 20k of the 100″ cars in 1955.

I concur that number three was most likely the primary motivation. Romney admitted in later interviews he went all-in on the new Rambler for 1956, ‘betting the farm’ as it were. At the same time, he recognized any held-over models sold primarily on price could divert sales away from the critical new car. He was savvy enough to see the Nash-Hudson cars were a dead end, only the weaning process for the dealers to see they had a viable new product was necessary to carry those until Rambler took hold. The precarious state of AMC finances at the time might have influenced the decision as well.

In affect, the increased prices on the all-new 1956 Ramblers somewhat repeated the initial Rambler introduction: sell to a premium segment as an acceptable second car that one need not be embarrassed by as a poverty-wagon. Henry J never understood that poor folks didn’t buy new cars then and definitely wouldn’t any new car that displayed their poverty for all to see.

Reintroducing the 100″ wb Ramblers to the recession-ravaged 1958 economy as price leaders was also a brilliant move. Romney certainly had a prescient grasp of what the American consumer would embrace.

What a tour de force of an article! It nicely fills in all the gaps about my knowledge of Rambler’s early history. For example, I didn’t realize the “all new” 1956 Rambler was a heavily reworked variant of the 108-in wheelbase 1955 Rambler.

Just one question — when did the 108-in wb 2-door sedan appear after 1956? I recall seeing a 1962 example on the street in the 1990s, but I’m thinking it must have been introduced some time earlier.

Regarding the other early American compacts, I don’t recall ever seeing the Kaiser Aero on the streets, but there was a fellow student in my elementary school whose parents had a Hudson Jet. This was around 1960. Also, I saw Henry J’s fairly regularly back in the day and even got to ride in one.

I believe that the two-door sedan reappeared for the 1962 model year.

Yes, 1962. And quite odd, given that it lasted all of one year. Yet they had to tool up new longer front doors and all. One of those great automotive mysteries.

This one appeared recently for sale in South Dakota:

Great overview of a tale I knew little about. Spotting a niche has become a key for many over the years. See SAAB Turbo or Combi Coupe, Peugeot 407 Coupe, or MINI for more details.

Interesting to see the 1951 ad captions a wagon as the “Rambler All Purpose Sedan”, which looks like a low content version of Greenbrier.IS this just virtue out of necessity or were Mason and Romney thinking “hatchback” as well as semi-premium convertible?