(first published 3/14/2012) In 1945, Corradino D’Ascanio found himself without much to do. Formerly an aeronautical engineer, the destruction of the Piaggio factories and the 10-year postwar moratorium on Italian aerospace development threatened to leave D’Ascanio without a future.

He was a talented engineer. At the age of 15, he built an experimental glider. During the 1920s he was highly productive, patenting a number of ideas in and out of the field of aeronautics. By 1930, he had created the D’AT3, an astonishingly capable early helicopter which won an international prize for a non-stop return flight of 8 minutes and 45 seconds. The records it set remained unbeaten for years, but despite an encouraging reception (Mussolini offered verbal support), funds dried up and D’Ascanio was almost broke by 1931.

His relationship with Piaggio began the following year, as an advisor on further helicopter development. But back to the story at hand.

Postwar Italy struggled to rise from its knees. Piaggio’s aircraft plants had been bombed by the allies and then mined by retreating Germans. Enrico Piaggio, son of founder Rinaldo, asked the Allies to return machinery that had been taken north from his factories to aid the German war effort.

Considering his circumstances, he struck upon the idea of providing very simple, low cost transportation with what little industrial capacity he had left. Road conditions were terrible, lending an advantage to 2-wheeled vehicles.

Development of what would become the Vespa began in 1944, but Enrico Piaggio was dissatisfied with the early prototype (the MP5, above). Meanwhile, Corradino D’Ascanio had been working on a revolutionary scooter design for Ferdinando Innocenti, another Italian industrialist who like Piaggio realised that cheap transportation was soon going to be in high demand.

Innocenti and D’Ascanio fell out over the construction of the frame – Innocenti wanted to use rolled tubing, to support his steel tubing company, and D’Ascanio wanted a unit spar frame. D’Ascanio left the project and was soon snapped up by Piaggio. Innocenti’s design would go on to become the Lambretta scooter.

Interestingly, both the Vespa and Lambretta were inspired by American Cushman scooters used by Allied forces during the war:

D’Ascanio immediately made it clear to Piaggio that he had an intense dislike of motorcycles. It was perhaps his hatred of them that led to several important advances; under D’Ascanio’s auspices the scooter gained a step-through chassis and an engine located next to the rear wheel, allowing the scooter to do without a dirty and ugly chain drive. Bodywork covered the engine and transmission, cooled by fan blades mounted to the flywheel, and the splash shield at the front of the Vespa kept riders relatively dry and clean compared to regular motorcycle designs.

The Vespa went on sale in 1946. Only 2,484 would be sold in the first year, but figures would skyrocket to over 60,000 units per year by 1950.

Fate smiled on the Vespa and saw it become a legend. Fate probably threw the Ape a confused expression, but it hasn’t been unkind.

In much the same way the Vespa was intended to get Italians themselves moving about, the Ape (Italian for Bee, a play on Vespa meaning ‘Wasp’) was intended to get businesses moving. D’Ascanio hit upon the idea in 1947: a light, inexpensive enclosed vehicle that could be operated without a license. The Ape would share many parts with the Vespa to keep costs low. Early models looked remarkably similar.

The cab arrangement seen on this Ape (found near where I work) wasn’t introduced until 1964; earlier models left the rider (or is that driver?) open to the elements. The 150cc Ape B arrived in 1952, but power was never a motivating factor – few Apes were capable of anything more than 20mph, but the torquey little two-strokes that powered them were strong enough to tackle uphill gradients even with a full load.

The Ape is essentially a load-bearing Vespa frame with an axle at the back, supporting a flatbed.

The basic vehicle has undergone few changes since its introduction. In 1968 the engine was moved to the rear for driver comfort for the first time, and the two current models, the 50 and the TM, have barely changed at all since 1993. The Ape 50 features a 50cc 2-stroke producing a curiously specific 2.58bhp. The more expensive Ape TM is available with a four-stroke 218cc petrol or 422cc diesel engine, producing 9.39 and 11.40 horsepower respectively. The diesel TM tops out at 39mph, and the petrol version is a little slower. The less said about the 50 in a straight line, the better.

The Ape may not win any races, but in countries where space is at a premium, they are indispensable. TM models can carry some 700kg in pick-up format, and the 50cc version can manage 200kg. With a turning circle of just 3.4 metres, it’s very nimble, and can be lifted up at at one end for tight turnarounds. The purchase price is low (though not in the UK), running costs are very low, and it meets all modern European emissions legislation. They’re common as muck in Italy, where weather isn’t so important and streets are narrow.

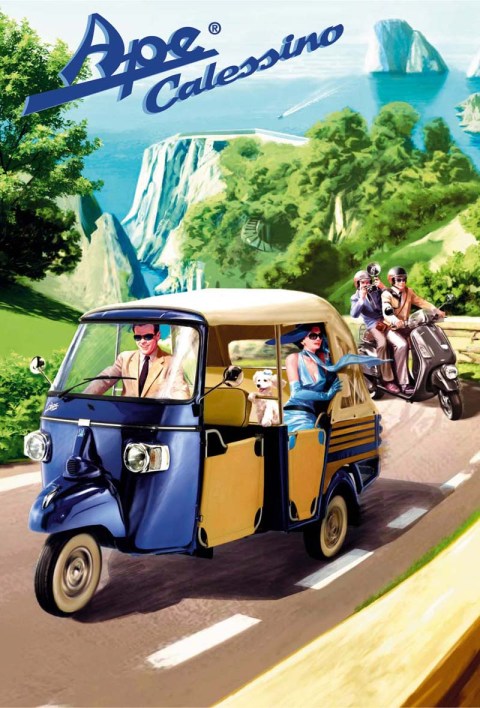

It’s sold in panel van, pick-up and tipper variants to the public, but the Ape has led a richer life than just that. They’ve been used as fire engines, police vehicles, trailer tractors and more unusual creations. In 2007, Piaggio offered the rather flamboyant Calessino model, limited to just 999 examples.

As well as being everyday workhorses, the Ape’s unique appearance makes it useful for attracting attention. Some are used as advertising billboards, and others are fitted out by third parties as mobile coffee stands or ice cream vans.

In many ways, it reminds me of another small, nimble and unusual worker:

Though I doubt donkeys have ever doubled as ice cream vans.

James, you have outdone yourself! What an excellent article about a vehicle (can hardly call it a car, can we?) that few know much about. Well done!

I am in China and have seen a few three wheelers, most notably one with a Chevy Spark body, same as the Deawoo Matiz. Saw it in a little hick town. Saw a few three wheel trucks in another hick town yesterday but was to busy watching and almost being involved in near death experiences to get any photos.

You mean like this? Why its the Snyder ST 600. Its even available in the US! Three-wheeled versions of the Prius and Peugeot 206 are also to be found. More dope here: http://carscoop.blogspot.in/2008/03/toyota-prius-peugeot-206-daewoo-matiz.html

and here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4wa5NDO6knY

Fantastic article! You mentioned once you will do a three wheeler but not a Reliant Robin. I hoped for a Piagio Ape though Morgan 3 wheeler also comes to mind but they must be very rare on the streets in Britain.

Ape is an amazing little workhorse (or should I say a workmule?). Here in the south of Europe they are still popular and have been around all my life. Often used by community services, they are perfect for working in parks or in pedestrian areas as well as tight streets of Mediterranean towns. A perfectly adorable little vehicle, I always felt that along with Vespas they add up to the charm of old Italian and Croatian towns.

Here’s my three-wheeler contribution – a massive Isuzu truck I photographed on Hwy 1 in Okinawa back in 1970. I wish it were a better image, but all I had was a $4.75 Instamatic! Why I never bought a decent camera in a land of cheap, great cameras…? Oh, wait – I was saving up for a stereo system and already owned a pretty good Polaroid 210!

There were a couple of small three-wheeled cars, Mazdas, I think, but I’ve never found any imagaes or info about them. I saw a couple while at Kadena.

That’s remarkable, I’ve never seen a three wheeler with such a long wheelbase. Good CC fodder.

That is impressive!

I own a Thai tuk tuk with the Japanese Daihatsu hi jet 649cc it is street legal in USA because it’s a motorcycle. There is a company selling eletric tuk tuks but they don’t do 60mph through the Holland tunnel

LOL at the first and last photo! Three wheeler week indeed.

In India, *several* generations of the APE are in production. The second gen is produced by Bajaj (originally licensees of Vespa and APE) as the Bajaj RE (Rear Engine), replacing the original Bajaj FE (Front Engine). It is Bajaj’s cash cow, and has four stroke 150-250cc engines, with an option of petrol/CNG/LPG power. Piaggio itself markets the later APE (with the diesel motor only) too. Several other manufacturers make other three wheelers based on Innocenti or Tempo designs. This is truly APE heaven, even if they’re called `Bajaj Auto’ here, short for Bajaj Autorickshaw.

Here is Bajaj’s latest (and most ambitious) take on the same chassis, called the RE 60.

Its no longer a three wheeler though. Lets see how it fares in the market.

I wish we could get the APE in the US. It’s all I really need for my 12 mile round trip daily commute. I’d like the TM pickup, with steering wheel.

In the late 90’s, I worked as a delivery boy for a carrier service, and I made the streets of Stockholm very unsafe with an Ape 50. They were quite common in Europe, but none so in Sweden, with its harsh regulation. In the middle 90’s, rules were relaxed and imports began of various and curious european vehicles, among them the Piaggio Ape. They were prohibitively expensive, almost as expensive as a “real” car. They fit in the “moped” rules, which called for max 50 cc engine size, and a speed limit of 30 km/h. The new EU-rules called for the same engine size, but the speed limit was raised to 45 km/h. Taxes and insurances were mandatory, but as they had no registration number, they couldn’t be fined for breaking parking regulations. In essence, it was a get out of parking tickets free card.

“My” ape was thoroughly worked over, some of the boys had gone over it with a hammer and chisel and made holes in the exhaust, essentially freeing the engine from the choking of the exhaust system. Which raised the speed limit to about 65/70 km/h. It ran like stink, and sounded like it too. It was sound polution galore, I can’t for my life understand how I wasn’t stopped. Fun times indeed…

Great article James. I have nothing to contribute with regards to the three wheeler feel compelled to tell you that the four legger is a donkey, not a mule.

Enjoy your work very much.

Thanks, it’s not really my area. Amended!

And a Jerusalem Donkey at that! Mean critters. Folks put them in with their cattle around here to “take care” of coyotes (they stomp them to death).

Now that you mentioned this, both Vespa and donkey were often sighted in Israel when I was growing up there in the 60s-70s. Here’s a typical Israeli street scene from the 70s.

…used in civvy street and by the forces, the below is an ex IAF one

The four legged variety is also still in use, particularly in the Wild South…

Yesterday TEMPO today the Ape. Wow Curbside classics goes downsized. I always admired people that drive this tiny vehicles – not a perfect choice if you want to stay unnoticed. But things are quite different in the southern Europe. By the way my neighbor ( and I don`t live in the southern Europe ) drives an Ape – he doesn`t have driving license.

I never heard of the Cushman scooter.

Also, never saw one in a WWII movie. You would have thought for authenticity that one would have shown up in a air base scene.

My contribution from Florence Italy.

I loved being in italy this fall visiting museo piaggio and seeing the ape in action. I have one on steroids in usa with a Daihatsu 650 cc top speed 120 kilometers per hour on a good road with no switchbacks. But lookin to trade for a mini or a fiat.

Great article James, I now see why italians thought the original Fiat 500 was a car. Vespa scooters or an Aisian knockoff have become popular here lately I chanced on a workshop full of them I guess the idea is they fit with the fake Mediteranian climate.

Please advise me if Ape are available in the USA. Thanks! Ricardo

Daihatsu tuk tuk in america I own it and love it.

Where did you get your tuk tuk albert?

Those two folks depicted in the artists rendering of blue and yellow Calessino look like they would be more at home in a 56 Imperial Southampton.

Very interesting article. I didn’t know Vespa built these types of vehicles.

I never knew Piaggio built any enclosed vehicles. I have owned 5 Vespa scooters, and still have a 1978 P200E

Dog: check out the Vespa 400

Impressive little machines. Amazing how much weight these tiny little 3 wheelers can handle.

I couldn’t help it…

Nice piece. My father would take us to Italy every four years or so in the 70s/early 80s and those three-wheelers were as ubiquitous as yellow, blue and orange Fiats. Never saw an articulated one though.

wow, i had no idea that these even existed or that piaggio started out making helicopters. speaking of three wheelers the elio reverse trike hjas been getting some buzz recently.

elio:

Neat little rigs .

About 15 + years ago a Tuk Tuk ” Dealer ” opened up on Lankersheim Blvd. in North Hollywood , Ca. ~ after driving by for a couple weeks and never once seeing and Customers , I stopped in , the rude Asian man inside didn’t want to talk to any one nor sell any of the three brandy new Tuk Tuk three wheelers parked out front .

Strange ~ I wish I’da had a camera .

-Nate

@Zackman That is Not an Isuzu. That is a Mazda T2000, the Big Mazda three wheeler. The small one is the K360: http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mazda_K360