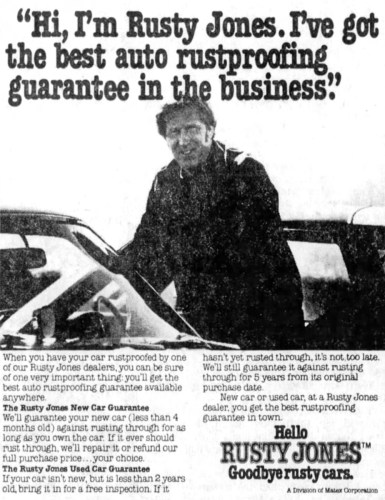

“Hi, I’m Rusty Jones.” For about a decade, he and his homely salutation seemed to be everywhere, greeting people in print ads, commercials and at car dealerships throughout North America. Then, just as suddenly as he appeared, he was gone. Rusty Jones became a household name when the aftermarket rustproofing industry suddenly expanded in the late 1970s, and his ascendancy had as much to do with a stroke of marketing genius as it did with the popularity of rustproofing. After all, even now, many people can instantly recall Rusty Jones… but how many folks can pull up similar memories of Rusty’s competitors such as Polyglycoat, Waxoyl or TekTor? A memorable name and image carry advantages, as Rusty Jones and his creators demonstrated four decades ago.

Rust, of course, has stalked cars ever since cars were invented. And wherever rust went, remedies followed. From early in the automobile era, repair shops and car dealerships occasionally offered “rustproofing” services, typically an oil-based spray to a car’s underside.

Manufacturers were not blind to this issue, and over time, many – with varied success – developed assembly-line processes to abate rust, and made other improvements like fabricating sheet metal for better drainage. But it never seemed to be enough. A Chrysler Corporation Corrosion and Plating Supervisor said in 1986, “We started improving our cars’ rust protection in the 1970s, but we were always behind the salt.”

Yes, the salt. During the two decades after WWII, salt took over from abrasive materials like sand as the treatment of choice for snowy or icy roads. Road salt use increased tenfold between 1950 and 1970. Heavy salt use enabled motorists to see bare pavement shortly after snowfalls; this quickly became an expected standard for highway departments.

Road salt became a billion-dollar industry by 1970, and in many respects, drivers didn’t miss the old ways of handling winter weather. However, progress came with a cost. In both storage and use, salt caused havoc – from ecological effects of salty runoff to quicker deterioration of infrastructure… to vehicle rust. In many cold-climate regions (the US Midwest and Northeast eventually became known as the Salt Belt), cars would develop visible rust after just two or three years. Along the way, this enemy of car bodies became a chief ingredient for the rising popularity of aftermarket chemical protectants… commonly known as rustproofing.

Salt alone, however, didn’t create the boom times for aftermarket rustproofing. A concurrent trend helped as well – that of prolonged vehicle ownership. Prior to 1960, consumers often viewed automobiles as little more than large disposable goods, keeping cars for just a couple of years before buying new ones. During the recessionary 1970s, though, that began to change. In 1976, the average new car buyer could be expected to own that car for 3.5 years; by 1981, that figure stood at 5.1 years. As a result, drivers became increasingly concerned with their cars’ durability, both from the perspective of their own use, and also how a car would hold its value for a trade-in that may be half a decade in the future. Rust was an enemy of these goals.

Typically, aftermarket rustproofing solutions were applied at service stations or body shops, and the industry had developed a somewhat unsavory reputation… not surprising given that the products were marketed by small companies, applied where customers couldn’t see it, and were rarely offered or endorsed by manufacturers or their dealers. But even given those headwinds, the industry’s North American sales increased every year.

Mater in the early 1980s

Among those paying attention to this trend was a young Chicago entrepreneur named Michael Mater. In 1965, at age 26, Mater founded a small company that produced industrial cleaning compounds. His firm, eponymously named Matex Corporation, had numerous business and janitorial companies as clients – among them a car dealer who asked Mater for advice on how to best clean a service bay where rustproofing was performed. The oily rustproofing solution sprayed and splashed when applied, creating a mess considered bad even by auto shop standards. After examining the mess, and seeing how the product was applied to cars, Mater thought there must be a better way to apply auto rustproofing.

Mater’s solution was to create a rustproofing compound with greater thixotropic properties (meaning a substance whose viscosity changes), thereby making a solution that could be sprayed on, but would then quickly turn into a gel-like coating. Such a product would better adhere to the car, would be easier to apply, and would create less mess. After several years of experimenting, Mater and his team achieved success. To memorialize this triumph of thixotropy, Mater called his new product Thixo-Tex – and it debuted in 1972.

For the next four years, Thixo-Tex was marketed to service stations and other repair facilities mostly in Salt Belt states, and sales grew slowly. Too slowly for Mater, who recognized that rustproofing was becoming a bigger business throughout North America. In 1975, Mater hired the advertising firm of Dawson, Johns & Black to devise a promotion strategy for Thixo-Tex. It didn’t take long for the ad team to realize that Thixo-Tex’s primary problem was its hard-to-remember, tongue-twisting name. Mater agreed; years later he admitted that “With Thixo-Tex, we had a memory problem.”

The ad agency and Mater himself considered about 180 potential new names, including Rust Patrol, Final Coat, and Nevermore. Ultimately, the folks at Dawson, Johns & Black concluded that a person’s name would be more memorable. T.T. Newbody and Rusty Jones were the finalists. Rusty Jones was suggested lightheartedly at first, but its catchiness meant the ad folks kept coming back to it. Marketing research showed that consumers reacted positively to the name, though Mater found that his own distributors were skeptical – saying that it seemed too homely and whimsical for a serious chemical compound.

Mater tested the new name in 1976. Several New York regions served as test markets for Rusty Jones, while the same product was marketed in other New York areas as Thixo-Tex. The test period (with heavy newspaper and radio advertising like the example above) was supposed to last for 90 days, but after just one month, the results were conclusive. For example, sales in Buffalo (a test market for the Rusty Jones name) increased 300%… compared to a 25% increase in the Albany area (which ran Thixo-Tex ads). Rusty Jones had won; the nationwide rollout of this new name started before test period was over.

With his ad company suggesting a persona to accompany the new name, Mater had a decision to make. Should he invest in an animated character or an actor? Even though it carried a heftier initial investment – for the artwork – Mater figured that an animated Rusty would have more long-term staying power, and Matex wouldn’t have to renegotiate an actor’s contract.

And thus was born one of the most recognizable trade characters of its time. Dawson, Johns & Black partner Marion Dawson said the character was meant to personify a “grownup Eagle Scout who lived down the street from you and liked to work on cars for the fun of it.” That sums it up perfectly. Rusty was friendly-looking red-haired man with a cowlick, wearing jeans, suspenders and carrying a red shop rag in his back pocket. The Rusty character not only presented a friendly image for Matex Corporation’s signature product; it also helped to soothe the slightly shady image problem the aftermarket chemical industry had developed.

Mater’s success, however, didn’t rely on the homespun character’s image alone. Another marketing innovation carried equal importance. Instead of continuing to sell his product primarily through body shops and service stations, Mater began marketing to new car dealers. It was a shrewd move, since the most compelling argument for rustproofing services could be made on the sales floor. Plus, with per-vehicle profits tumbling during the 1970s, dealers were eager for additional profit-generators. Within a few years, this became the industry norm, and ushered in the brief golden age of aftermarket rustproofing.

Accompanying the name change and focus on dealer sales was a tenfold increase in the firm’s advertising budget, which reached $3 million by 1981. Rusty’s ruggedly lovable image was everywhere – on print ads, on TV, on every Rusty Jones product, and often as full-size cutouts on showroom floors and at car shows. These investments in marketing and advertising paid off. Within five years of the name change, Mater and his company generated a 16-fold increase in cars serviced. The new name and new manner of selling its product made Matex Corp. a textbook example of marketing marvels (literally… Rusty Jones case studies appeared in numerous business textbooks during the 1980s and ’90s).

New car dealers sold rustproofing services such as Rusty Jones for $100-$250 – often with half of the total cost being profit. The price could be folded into vehicle financing, making the outlay more palatable for many consumers, especially in moderate-climate areas that were not historically heavy sources of rustproofing sales.

Rusty Jones wasn’t alone in the rustproofing marketplace. More than a dozen other brands had a significant North American presence, along with countless smaller, local brands. The largest was Ziebart, which had 800 worldwide franchises in the early 1980s, and relied on independent franchises as opposed to dealerships. Other brands such as Tuff-Kote Dinol, Metal-Gard (made by Quaker State), TekTor, and the European import Waxoyl competed for dealership attention. However, Rusty Jones was far and away the most popular dealer-supplied rustproofing product. The products themselves were largely similar – differences were largely in marketing, ease of application, and customer/dealer support.

So, just what was this rustproofing substance made from? Oil, mostly… mixed with solvents containing rust dissolvers and other compounds. However, the oil was the most critical component, because once sprayed onto the underside of a car, the solution never completely hardened. Instead, sprayed-on rustproofing material remained malleable for years, and could even reseal itself if nicked or chipped.

It was important to achieve the right amount of viscosity (hence Mater’s experiments with thixotropy) because the product needed to be sticky enough to coat a car’s underbody, yet aqueous enough to seep into hard-to-see crevices where rust often starts. Rusty Jones and other rustproofing solutions were sprayed on with wand-like applicators, and in theory, the product became like a film protecting metal from the elements. Unfortunately, theory didn’t always match reality.

Although dealer-sold rustproofing may have been profitable for dealerships and convenient for customers, the process often resulted in shoddy workmanship. Companies like Rusty Jones provided training for dealerships’ employees, but there was often no accountability for a job well done. While it was relatively easy for customers to spot newly-applied rustproofing on a car, it was not easy to figure out the quality of that application.

Dealer-applicators often cut corners, insufficiently spraying areas that weren’t visible. This was particularly true when the applicator drilled holes to access the interior of panels – often a quick spray would substitute for a thorough coating in these unseen areas. Worse, existing weepholes were occasionally clogged by the oily rustproofing substance – and blocked drainage holes trap moisture inside body panels, which leads to… rust.

These sample warranties were provided to car dealers. Oddly, while the sample vehicle is a Mercedes with a fictitious VIN, this had the name and home address of Powell Johns, president of Dawson, Johns & Black, the ad agency that created Rusty Jones.

New car customers tended not to worry much about the thoroughness of the application, though… because the product was warranted. In fact, the ability to back up marketing claims with warranties was the key to rustproofing companies convincing dealers and customers that they were legitimate. Rusty Jones trumpeted its “full, unlimited, transferable rust and paint protection warranty,” which seemed mighty generous. But how many people actually read the fine print in a new-product warranty? Turns out there was plenty of fine print.

To keep the warranty valid, owners needed to take their cars to an authorized Rusty Jones dealer every year for a free inspection. Dealers liked this arrangement, because it brought customers back into the dealership, making for good future sales prospects. Actual inspections were often cursory. As for any warranty rust repairs, dealers often tried to put that off as much as possible. Matex offered dealerships “benefit sharing” arrangements whereby it reimbursed dealers a portion of their initial cost outlays (such as the cost of materials) based on the amount of warranty claims received from their work. So while Rusty Jones instructed dealers to address any early rust issues, these were often pronounced as not covered by the warranty. At other times, only a superficial repair (or recoating) was done… likely in hopes that the customer wouldn’t come back for subsequent checkups.

Rusty Jones wasn’t alone in practicing warranty shenanigans; it was the industry norm. Soon, the combination of a costly product, sloppy workmanship, and unaccommodating warranties meant that consumer complaints piled up. Several US states investigated rustproofing companies and their warranties, and the results were often critical to the industry. A 1980 New York Attorney General’s report titled A Tarnished Option concluded that most rustproofers’ warranties carried “limitations or conditions that render them essentially worthless.”

Also in 1980, Ohio’s Attorney General required dealers to stop using the term “rustproofing” in favor of vaguer terms like “rust inhibitors,” and tightened up allowable warranty terms. Other states investigated as well, often urging customers to exercise caution in purchasing rustproofing services.

These investigations and suspicions, however, didn’t corrode the rustproofing industry. In 1981, Rusty Jones serviced 800,000 cars at 2,700 US dealers, accounting for about 20% of the rustproofing market – nearly twice that of its nearest competitor. Throughout much of North America, customers could barely find new cars that had not been rustproofed, with many dealers treating their entire inventory immediately upon arrival.

To be fair, aftermarket rustproofing wasn’t always meritless. Many customers experienced positive results – this 1982 Suburban, which sports the sticker in this article’s lead picture, looks pretty good for a 40-year-old vehicle. Oil-based rustproofing solutions are still used as supplemental rustproofing in cold-climate areas today, and they do suppress rust if applied correctly. But insufficient squirts of the stuff, as often done at dealerships, tended to do very little other than expand dealers’ profit margins.

Even when aftermarket rustproofing services were at their peak in the late 1970s and early ’80s, many analysts thought the industry had a limited lifespan. Initially, the looming trouble seemed to be cars made increasingly of plastic. Rustproofing companies tried to hedge their bets and offer other car-care products (Rusty Jones did this as well), but most of these companies still relied overwhelmingly on rust services. What ultimately skewered Rusty Jones and the whole industry wasn’t plastics… instead, the industry was done in by its very success.

With aftermarket firms cashing in on a service that consumers felt was important, automakers took notice. Factory rustproofing efforts gradually improved. In 1979, American Motors (which contracted with Ziebart to treat cars on the production line) offered a 3-year “No-Rust-Thru Full Warranty.” The Big Three quickly followed – prompting AMC to increase its own coverage to 5 years for 1980 – and the race was on. Still, the aftermarket industry was unfazed. Mater said at this time that “the impact of manufacturer warranties is positive on our sales; it has made the customer aware of the need for rust protection.” Mater and his counterparts noted that people who keep their cars for longer than three or five years still need additional protection. Plus, those early manufacturer warranties were rather stingy. Like one Tuff-Kote executive said: “Who expects their car to rust through in the first three years?”

Many Americans never heard of Beatrice before its 1984 ad blitz. The company started dismantling just a few years later.

The early 1980s represented Rusty Jones’s pinnacle. At exactly that point – in 1984 – Mater sold his company to Beatrice Foods, a conglomerate that spent much of the 1980s acquiring businesses outside of its traditional food processing sphere. Beatrice paid an undisclosed amount for the rustproofing company, and retained Mater with a five-year contract as president of their new Rusty Jones Division. In the heady world of 1980s corporate takeovers, what followed was somewhat predictable. Against Mater’s advice, Beatrice gutted most of his former company’s resources and slashed advertising budgets. Rusty Jones immediately began losing market share – a situation made doubly worse since aftermarket rustproofing in general was quickly losing its appeal. Only meager efforts were made to expand the division into more sustainable lines of business such as other car-care supplies.

The Decline and Fall of Aftermarket Rustproofing came quickly. Manufacturers realized both the profit potential and the customer appreciation payoff in applying enhanced rustproofing at the factory. By the late 1980s, manufacturers had increased their use of corrosion-resistant materials like galvanized steel, as well as processes like cathodic electrocoating or applying chemical protectants such as phosphate sprays at the factory. GM and Ford soon offered 6-year/100,000-mi. corrosion coverage; other manufacturers followed suit.

Comprehensive factory corrosion warranties meant that consumers found it tough to justify additional outlays for services such as Rusty Jones. In fact, by 1988, some GM owner’s manuals included a notice that “…the application of after-manufacture rustproofing is not necessary or required.” Although many dealers persisted in selling these services – marketing them as “You can never have too much protection” – the services soon reacquired much of the consumer distrust that they shed a decade earlier. Rusty Jones’s business plummeted accordingly. Between 1985 and 1988, the firm’s distribution network declined from nearly 3,000 new car dealerships to 1,800. As an example of the industry’s quick contraction, in 1989, the head of a Washington, DC auto dealers trade association said bluntly “The whole metropolitan area is dead” for dealer rustproofing sales.

Rusty Jones’s final years reads like a horror story from the world of leveraged buyouts. By the late 1980s, Beatrice acknowledged that Rusty Jones had “warranty problems” (though the Rusty Jones subsidiary was structured so that Beatrice itself incurred no liability). In November, 1988, Beatrice sold Rusty Jones, as well as a few other nonfood entities, for $26 million to a holding company that was (confusingly, corruptly, or both) controlled by a former Beatrice CEO. Just three weeks later, this group in turn sold Rusty Jones to another investment group headed by Chicago businessman Charles Wortman… for the measly sum of $50,000 (Mater relinquished his last stake in the company at this point). Wortman figured that the Rusty Jones name itself had investment potential, but Beatrice’s “warranty problems” was an understatement. $1 million of warranty claims were being applied for each month, and Rusty Jones’s total assets amounted to $6 million in physical resources and a signature product that was no longer marketable. On December 5, 1988, Wortman’s group put Rusty Jones into Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

Even after the bankruptcy, Wortman still had hopes for the Rusty Jones name, figuring that he could pivot the company heavily to services such as interior and paint protection. Although Ziebart successfully did just that (moving into window tint, sunroof installations and other services in the 1990s), the Rusty Jones name never came back.

Rusty Jones is remembered mostly for its animated character, robust advertising, and a product that often didn’t seem to work. More than that, though, Rusty Jones is the personified image of the brief glory years of aftermarket rustproofing. With deft marketing and a focus on selling directly to dealerships, Rusty Jones helped to spring the entire industry into those good times, and dissolved like rust itself once the party was over. Goodbye, Rusty Jones; it was good to know you.

I had a Dodge Dealer add Rusty Jones to my brand new 1978 Aspen before delivery. They plugged the drain holes in 3 of the doors and both sides of the trunk which I didn’t discover until it all rusted out the next year. RJ would not cover it under warranty claiming it was the dealer’s fault for not applying it correctly.

Thanks for the essay! I stumbled across an old Rusty Jones advertisement this morning and it seemed so familiar. I was born in ’81 in a Salt Belt state so my impressionable years were they heyday of Rusty Jones. I’m sure I saw the ads and stickers everywhere without having the faintest clue what “rustproofing” was! I’m glad to have found your great essay this morning to clue me in, after forty years!