(l. to r.) Hans Nibel, Ferdinand Porsche, Paul Jaray, Hans Ledwinka, Edmund Rumpler, Adolf Hitler, Josef Ganz

Success has many fathers. No wonder so many are eager to share in the paternity rights of the Volkswagen, the world’s most successful and long-lived car. Some have had books written and documentary movies made to stake their claim; others have sued in courts of law and the court of public opinion, in articles, books and the internet. The essence of their claims is that one person conceived the initial novel idea of a Volkswagen, or its unique technical aspects, or the iconic shape of the Beetle. Drawings, models, prototypes, production cars, and other evidence to litigate their claims are used, from the 1930s right into the present, and likely into the future.

Many of these claims have found considerable traction, including court settlements and favor as well in the court of public opinion. They reflect the innate human tendency to want to give credit for a success to a single person. We love heroes and winners, and it’s much easier to judge things in black and white, and to rely on isolated pieces of evidence or commonly held assumptions for determining the true winner or hero.

The following is an exercise to look more closely at some of the key claimants and their roles in the birth of the Beetle, as well as to look at some lesser known automotive pioneers whose work influenced the primary claimants as well as the final product. The reality is that technological and design advances are almost never made in isolation which makes this task more difficult. It’s inevitably not truly comprehensive, but it is an effort to shed light on the Volkswagen’s long gestation and DNA.

One thing we know for certain going into this lengthy exercise: The baby Volkswagen is Austrian. Every one of its paternal candidates pictured above was Austrian or ethnic Austrian. No wonder I’m a bit obsessed with the Beetle.

Part 1: Henry Ford – The Godfather

Henry Ford undoubtedly was the godfather of the Volkswagen. Although Ford’s dream was to make the automobile more available to the masses, he didn’t exactly set out to build a true “People’s Car”, given that his new Model T cost $850 in 1909. This was at a time when a worker made $200-400 per year, and an accountant or dentist made some $2000 per year. That was more than most “real” cars on the market, which were largely accessible only for the truly wealthy.

Ford’s T was a conventional and pragmatic car, in the formula laid down by the seminal Mercedes of 1901: a strong steel frame to support the body, a water-cooled inline engine in front driving the rear axle via the transmission and drive shaft. Henry had his ideas about some of the details and execution, which was to a very high standard, but there was nothing really new or revolutionary about its design.

The Fordian revolution was all about production. As Ford plowed his profits back into ever more efficient production facilities and methods—inventing the rationalized automotive assembly line in the process—the cost to build and buy a Model T plummeted. This created a virtuous loop: the lower the price went, the more sales increased. By 1914, a relatively well-paid Ford worker could buy a $490 T with four month’s pay. By 1925, the price dropped further, all the way to $260 for the two passenger roadster (the enclosed sedan cost $660); now the T was truly affordable to the working class. Production topped 2 million in 1923 alone. Henry had created the second American Revolution, and the rest of the world wanted to share in it.

That applied especially to Europe at the time, and Henry wasted no time exporting the T, with local production of bodies and many other key components, such as the Trafford Park plant in the UK above. Although Model Ts accounted for fully half of all the world’s cars ever built by the early twenties, the Model T was way too big, thirsty and expensive to become a true People’s Car in Europe. It was strictly for the well to-do, if not the truly rich. Something different was needed, for the very different circumstances in effect there.

There had been all manner of crude small cars and cycle cars in Europe ever since the car’s invention, but these were inevitably marginal undertakings. The motorcycle was the closest thing there was to an entry-level car. So Europe’s biggest manufacturers took to creating cars in the Model T’s vein but substantially scaled down. A flurry of mini-Ts appeared in each of the major countries.

Citröen’s 5CV of 1921 was perhaps the prototype of the genre, or at least the first one built on a relatively large scale. Citröen was the pioneering adopter of Ford-style production methods in Europe, and some 80,000 5CVs were built in its four year production life. Its 11 hp 856 cc four was representative of this class of cars.

The British Austin Seven went into production in 1922, and was both very successful and influential. It was even built in the US as the Bantam and in Germany as the Dixie, a forerunner of the BMW.

In Germany, the Opel 4 PS, known as the “Laubfrosch” (tree frog) arrived in 1924 looking heavily influenced by the Citroen 5CV. The Laubfrosch was a relatively big hit, and catapulted Opel into Europe’s biggest volume auto manufacturer, undoubtedly why GM bought Opel in 1929.

And although it came along some ten years later, the Fiat Topolino was in the same mold. All these cars (and others in their class) were of course substantially smaller than the Model T, typically two-seaters. This was due to high taxation and fuel costs, as well as to keep production costs as low as possible. Europe’s market was highly fragmented, and no manufacturer had the scale to even remotely approach Ford’s efficiencies. The Opel came perhaps the closest, with some 120k built between 1924 and 1931, and its price dropped from 4500 RM to 1990 RM in 1930. But that’s still only some 17k per year, in a country of 65 million, which was more than half the population of the US at the time. Although cars per population in the UK and France were far below that of the US, Germany was substantially behind them even. The country that birthed the car was a laggard in its adoption.

These “Mini-T” cars were all highly conventional in their conception and construction. But they were still only affordable by the solidly upper middle class at best; professionals, small businessmen and such. The working class person was still stuck dreaming of an affordable car while pedaling their bike.

Although the major manufacturers generally had little interest in attempting to build even cheaper cars, it became something of a Holy Grail for forward-thinking engineers, designers, dreamers, and even certain political figures. And it was increasingly clear that the solution was likely to include some radical new ideas and technology.

For that matter, the automobile in Europe was ripe for reinvention, small or not so small. The 1901 Mercedes formula mostly worked well enough for large cars, where its deficiencies could easily be masked by its size, weight and power. But new ideas of how the automobile could be conceived and designed were brewing, and although that would come to affect all the classes of cars in Europe eventually, it was with smaller cars where the greatest benefits were seen.

Before we delve in to the contributions of the various gene donors, it’s essential to debunk the common idea that the VW, like so many other “inventions” was the result of a Eureka moment experienced by its isolated creator hunched over a drafting table. Truly novel inventions are exceedingly rare; invariably a number of individuals or organizations are chasing after the same goal, their efforts based on previous inventions and research, and constantly feeding off the fruits of others engaged in the same quest.

Charles Darwin wasn’t the first to propose evolution, and Edison didn’t invent the light bulb. They, and so many acclaimed scientists and inventors were competing with others, and constantly exchanging information. And in the case of Edison as well as Ferdinand Porsche and others, they were really the managers of the process and the efforts of many employees in their charge. But the person at the top inevitably gets (or seeks) the lion’s share of the credit.

Part 2: Edmund Rumpler – Head In The Sky

Born into a poor Jewish family in Vienna in 1870, Edmund Rumpler was infatuated with heavier-than-air flight early on. Since this was not yet a reality, after he graduated with an engineering degree in 1895 he hitched his star (temporarily) to the nascent automobile industry. At the tender age of 25, he was made the Technical Director of the Nesselsdorfer Wagon Works (in what is today the Czech Republic), a manufacturer of railroad carriages eager to expand into automobiles. His assistant in that undertaking was another of our paternity claimants, an even younger 18 year-old Hans Ledwinka. Nesselsdorfer would eventually become Tatra, and Ledwinka would have a brilliant career there. But Ledwinka owes Rumpler more gratitude than just giving him his first job.

Rumpler and Ledwinka’s first car at Nesselsdorfer there was a flop, due to a faulty engine, a recurring issue that would bedevil Rumpler. He moved on to Adler in Berlin, where he was unhappy with the simple and crude chain drives then commonly in use, as well as the excessive weight of the alternative shaft drive rear axles. So in 1903 he invented and patented something truly new and original: the swing axle, the first driven independent rear suspension.

A prototype was built, but there were problems with the very small, hard tires of the time coping with the camber changes. So Adler passed for now, although the ball-joint torque tube, another of Rumpler’s inventions was used and eventually went into widespread use internationally. The swing axle would have to bide its time until both Rumpler and Ledwinka (and others) would separately put it to good use.

Here’s the brilliance of the swing axle’s design as used by many that adopted it, particularly so Tatra. It dispensed with any expensive and easily-worn universal joints; as can be seen here, each half shaft’s large ring gear can swing freely in an arc around the (small) driveshaft pinions. The two half shafts are located by the two round guide shoes inside the round case.

Here’s the same basic design as used still in today’s Tatra trucks, which are legendary for their off-road prowess and durability.

VW had a different type of joint, using a ‘tang” inside a differential gear, with fulcrum plates. Also very tough, simple and rugged, although in principle not as much so as the Tatra style. But the VW was optimized for lower cost mass production.

In any case, until better IRS systems came along, swing axles were the way to go.

As powered flight became a reality, Rumpler’s first interest took flight too. He acquired the German license for the Austrian Taube (“Dove”) designed by Igo Etrich in 1909. An elegant and advanced design, Rumpler was soon building them in significant numbers for various uses, including for the military during WW1. Rumpler designed an advanced V8 engine for it, but (once again) it was not successful, and most were powered by a Daimler four cylinder. The Taube made Rumpler successful and famous.

He went on to found Rumpler Air Service, a pioneering transport service in Germany, flying one or two passengers in the small planes of the time.

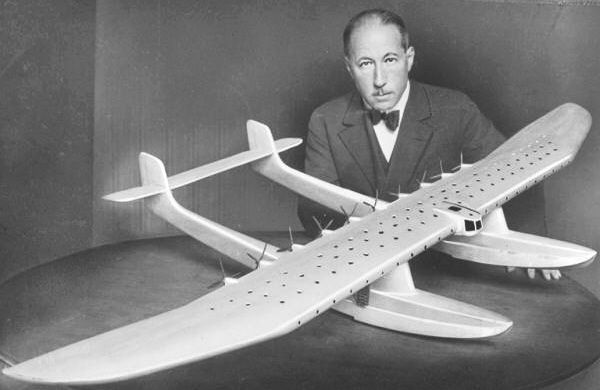

But Rumpler thought big, and he was the first to conceive in considerable detail the very far-reaching idea of international heavier-than-air transport. In 1921 he created The Trans-Oceanic Company, and in 1927 unveiled this concept of a giant ten-engine flying-wing amphibious plan seating 175 passengers. It was simply too far ahead of its time, so he turned his attention back to cars.

Given how critical aerodynamics is in aviation, it’s no surprise that Rumpler made aerodynamic efficiency a key element in his thinking. Undoubtedly he was aware of the 1913 Alfa Romeo that had been rebodied by Carrozzeria Castagna at the request of Count Marco Ricotti. It was a one-off, and due to excessive heat from the engine inside the body in its unusual place, it soon was turned into an open car, negating some of its slipperiness.

Rumpler’s Tropfenwagen (“Tear Drop Car”) of 1921 approached the problem quite differently, as it was anything but a mere streamlined body on a conventional chassis.

The Tropfenwagen sat on a revolutionary chassis, one that is essentially akin to the “skateboard” chassis that underpins Teslas and an increasingly number of current EVs. This is looking at it from the rear, and we can see the swing axles with quarter elliptic leaf springs and control arms. Just ahead of that is the four-speed gearbox, and then the very unusual 2.3 L W6 engine, with its three banks of two cylinders to make a very short and rigid engine, in the rear-mid location of the quite light built-up steel “frame”. Ahead of the engine there were openings in the frame to allow the storage of two spare tires.

This shows the location of the engine and the radiator directly behind it, whose hot air was exhausted through vents in the car’s tail.

The Tropfenwagen was less of a production vehicle and more of an on-going design/engineering exercise to entice existing car manufacturers to license it. Hence a number of different body styles and sizes were built, from 6-7 seater limousines to a rather compact open car and coupe. In part this was to show the flexibility of the concept, as well as to see which ones attracted the most interest. Some 20 of these various first series Tropfenwagens were built, including two sent to the US to attract American car makers, powered by a Continental six cylinder engine. Rumpler’s W6 engine again had some deficiencies, thus the later versions used a Daimler four.

It’s hard to say what was the most revolutionary or influential aspect of the Tropfenwagen; its aerodynamics or its extremely advanced and unique chassis, IRS and drive train. But at least we can put a hard number to its aerodynamic drag, which Volkswagen did in 1979 in their new advanced wind tunnel. They tested a Tropfenwagen, a 1940 Tatra 87 and a 1939 Kamm prototype sedan. Here are the hard numbers:

Although the Rumpler had a significantly greater frontal area (“A”) due to its much greater height, its coefficient of drag (Cd), or the relative aerodynamic efficiency of its shape, was so much lower at 0.28 to make up the difference and still have the lowest overall aerodynamic drag (“CdA”). As such, the Tropfenwagen’s 0.28 Cd was not equaled by the most aerodynamic production cars until the mid-late 1980s, a truly stellar achievement. And it explains how it readily exceeded 60mph (100kmh) with only 36 hp.

Although the Tropfenwagen were not really successful per se, but Benz did buy a license as it clearly saw its potential. That’s in Part 5. And of course Hans Ledwinka at Tatra adopted its swing axle rear suspension, which is still on Tatra trucks today. The swing axle was taken up by numerous makes, primarily German and Austrian firms, who placed a high value on the better ride they afforded.

And within a few years, Ledwinka would take up the aerodynamic theme with a vengeance.

The Tropfenwagen was too far ahead of its time, but its influence was vast. It was the prophet of the aerodynamic age and the Volkswagen was very much a product of that. It ignited a wave of aerodynamic rear engine concepts and actual cars. One of these early ones was this one designed by Sir Dennistoun Burney; his Burney Streamline of 1930 was one of two more obvious intermediate steps between the Tropfenwagen and the Tatra 77 of 1933. Unfortunately, its long and heavy water cooled six cylinder engine protruding from the rear was not ideal. The consequences of too much weight on the rear wheels of a rear engine car would soon make itself known, and significantly affect the design of the Beetle.

Rumpler moved on to FWD, although not successfully. His career came effectively to an end in 1933, given his Jewish birth. His wife and children moved to Vienna, but he stayed behind, sold his company to Ambi-Budd, the German branch of the Budd Company, pioneers in steel car body building and employer of engineer Joseph Ledwinka, brother of Hans. Rumpler consulted to Chrysler on suspension issues and such, and died of natural causes in 1940.

Part 3: Paul Jaray – Aerodynamics Is King

Paul Jaray was also born into a Jewish family in Vienna, in 1889. After his education and some time as an assistant at the Prague Technical University, he became an aerodynamicist, working first for Flugzeugbau Friedrichshafen, on sea planes.

His first claim to fame was in designing the Zeppelin Airship Bodensee, which was a breakthrough in airship design, thanks to its advanced aerodynamics. Through extensive wind tunnel tests, Jaray substantially changed the ratio of diameter to length from preceding Zeppelins, resulting in a very significant reduction in drag and corresponding increase in range. The Bodensee was the prototype of all subsequent rigid airships.

Jaray used his aeronautical experience to develop a specific formula for automotive aerodynamic design principles that led to a patent, applied for in 1922 and issued in 1927. His approach was influential, and numerous companies used Jaray licensed bodies during the streamlined era that unfolded in the early thirties.

Jaray built streamlined bodied versions of Mercedes, Opel, Maybach (above), Ford, Chrysler, and numerous other makes. It became something of a formula, resulting in look-alike cars. Although Jaray’s work was influential, and eventually variations on his themes became near-universal.

Jaray had to sue Chrysler, as it was all too obvious that their 1934 Airflow was a bit too much under the influence of his work and patents.

After Hans Ledwinka decided to build a large streamlined car, Tatra bought a license and paid Jaray to provide the expertise to develop them, including the 1934 T77.

We’ll take up the actual VW’s development a bit later, but this wooden buck of its definitive body design by Erwin Komenda from 1937 clearly shows the influence of Jaray, even if his patent was expired or ignored by this time.

Part 4: Josef Ganz – Advocate and Agitator

Josef Ganz was born into a German-speaking Jewish family in Budapest, but they soon moved to Vienna and then Mainz in Germany. He fought in WW1, and completed his university-level engineering degree in 1927, by which time he became inspired by the idea of a small car for the price of a motorcycle. That was hardly a novel dream, but Ganz took up the cause with a passion.

Ganz’s cause was inspired in part by his experience as owner of a second-hand Hanomag 2/10 PS (above), lovingly called the “Kommissbrot” (“Commissary Bread Loaf”). It was a pioneer in its own right, and played a significant role in the development of future small cars and the Volkswagen. The Kommissbrot was really quite revolutionary for 1925, with its radical full-width and low-slung body.

Although it was built on an assembly line, Hanomag was not able to price the Kommissbrot low enough to undercut the established conventional cars like the Opel. Hanomag eventually replaced the Kommissbrot with a conventional sedan in 1930, but not before they sold some 16,000 of the little loaves.

The Hanomag had a single cylinder 499cc engine that made 10 hp and was mounted in the rear over the chain-driven axle. To keep costs down, it made do without a differential and had rather crudely sprung solid axles front and rear. Ganz was determined that any small car he designed would have a more sophisticated suspension.

Ganz began to sketch small cars that were essentially scaled-down Rumplers, with mid-rear engines, swing axles, and small aerodynamic bodies. After his graduation, Ganz became editor of Klein-Motor-Sport, and undertook a campaign to advocate for advanced new small cars, railing against the established manufacturers for their conservative mind-set.

After tirelessly hounding manufacturers to get on the lightweight rear-engine bandwagon (despite Hanomag’s decision to exit that market), he finally secured a development contract with Ardie in 1929, resulting in the 1930 Ardie-Ganz prototype (“Maikafer” or “May Bug”), seen here with Ganz and Paul Jaray (right). As can be seen, this is essentially an update of the Kommissbrot concept; a very small, light open two seater. Its front “radiator” is a dummy.

That resulted in the 1931 Adler Maikäfer prototype. It is on the basis of this car that Ganz claimed to be “the engineer behind the Nazi Volkswagen”.

The 1933 two-passenger Standard Superior was the first production car built to Ganz’s design standards and patents. It had a mid-rear mounted 12hp 396cc two-stroke engine, tubular central chassis, fully independent suspension, a rather crude wood body covered in “artificial leather” (vinyl), and priced at 1590 RM. But it was a whole class or two smaller, slower and less capable than what Hitler envisioned for his Volkswagen.

It used a tubular central frame (which was not new), independent suspension front and rear, using two sets of transverse leaf springs to locate the front wheels and one in the back in conjunction with the swing axles. That was not new either, but it certainly was an improvement on the Kommissbrot’s solid axles.

The little two stroke twin is on one side of the center tube, and the transmission on the other. It was a space efficient way to package the drive train, but one does wonder about issues of noise and heat emanating from it, as well as access for servicing. VW tried for years to make that work on its EA266, which was intended to replace the Beetle, but they finally gave up for those reasons and went with FWD (Golf).

The chassis with its mid-rear engine and swing axles was essentially similar in concept to that of the Rumpler Tropfenwagen, scaled down considerably.

Later in 1933, the body was revised due to wide criticism of the original, to include a small rear window for any children that might be squeezed into its very small back seat over the engine. The engine was increased in size to make 16 hp. But it was still essentially the same car, and still used wood covered with vinyl for its body.

Standard used the term “Volkswagen” in its advertisement (“the fastest and cheapest German Volkswagen”). This was not used as a brand, but generically, since the term had been in common usage for some time.

There’s even a video of a restored Standard Superior, so that one can enjoy the sound and sight of its nattering and smoky little two stroke engine.

Ganz was arrested by the Gestapo in 1933 for supposedly blackmailing the German auto industry. He was later released and fled to Switzerland, where he developed the same basic concept into “The Swiss Volkswagen”. The prototype chassis is seen above. It may have four wheel independent suspension, but it’s not much more than a two-passenger go cart otherwise.

Some 40 similar small cars were built locally, but Ganz ended up embroiled in years of lawsuits there and in Germany over his designs and patents. He eventually moved to Australia, where he did a bit of consulting and passed away in relative obscurity in 1967. But not before an article was written in which he claimed to be the forgotten father of the Volkswagen Beetle.

There has been a considerable campaign to establish Ganz as just that, with a book, documentary and website dedicated to that cause. I haven’t read the book, but just watched the documentary. I found it somewhat embarrassing, for the many distortions of facts and the absolute unwillingness of its makers (including a descendant of Ganz) to 1.) accept that there were already small cars like the Kommissbrot; 2.) that others were also working towards similar goals, and 3.) that there was a large gulf between his vision and version of the Volkswagen and the ones by Hitler and Porsche. But like many such documentaries it has a specific goal, to advocate for a cause and do so by playing on the viewers’ emotions, never mind the facts, of which 99% of the viewers will be ignorant.

In that same year (1931) that Ganz built his little Adler Maikafer open two-seater, the car that he claimed was the true basis of the Volkswagen, the Type 12 was taking shape on the Porsche drawing boards, a speculative design for a compact air-cooled rear-engine 4/5 seater all-steel sedan. We’ll get to that later, but I’ll let you draw your own conclusions as to which one was more influential on the Beetle.

There’s also this design for a “people’s small car” by Béla Barényi, made sometime between the years 1925 and 1931. He made numerous sketches and proposals, one of which ended up on the cover of Ganz’s Motor-Kritik magazine. I can’t give him a chapter of his own, but in later years, in a drawn-out legal battle, he finally won his claim that the drafts he had made as a student of the “future people’s car” be recognized as the “intellectual parent” of the Volkswagen. That’s precisely the same claim Ganz made the rest of his life. That court claim is according to one source that I can’t confirm. And judges aren’t always right.

Meanwhile in Italy, all the way back in 1924, the San Giusto was a production car that was years, if not decades, ahead of what Ganz, Ledwinka, Porsche, Nibel and the others in Germany were doing or just dreaming of.

Designed by Cesare Beltrami, the San Giusto had a light alloy backbone chassis(!) featuring double-wishbone fully independent suspension front and rear(!), meaning no swing axles. Undoubtedly influenced by the Rumpler Tropfenwagen, it had a mid-rear 748cc vertical four cooled by a top-mounted blower. And it had front brakes, noticeably absent on Ganz’s car.

Here’s another view of this delightfully light and highly advanced chassis. Only some 20 of these cars were built, undoubtedly because of the difficulties in making its production economically viable in Italy at the time.

That’s not to suggest that Beltrami was the first to design and build a non-swing axle IRS. The 1915 Cornelian, backed by Louis Chevrolet and the Blood brothers, qualified in the 1915 Indy 500 with Chevrolet at the wheel. It used upper and lower transverse leaf springs front and rear to locate the wheels, and double-jointed drive axles. And it even had a primitive form of rack and pinion steering. A production version was contemplated.

My point is simply that there were other more advanced cars that had been actually built, sold and raced before the time of Ganz’s designs and those of others.

There is no question that Ganz played an influential role in the early days of the movement to create a small affordable car in Germany. And that he contributed technically to the cause with his own cars as well as by consulting with Mercedes and other manufacturers at the time. And it’s painfully clear that Hitler was not about to let him continue playing that role, cutting short a career that might well have played a more significant role at the right company. That alone speaks volumes about the times, but it does not quite confer paternity.

Part 5: Hans Nibel – Benz and Mercedes Give Rear Engines A Try

Hans Nibel was born in 1880 in Moravia, then part of Austria-Hungary and now in the Czech Republic. After graduating from the Technical University in Munich in 1904, he went to work for the pioneering automobile manufacturer, Benz & Cie. (Company). He was promoted regularly, and by 1911 was an officer and Chief Technical Director, and by 1922, he was a board member. He was of course involved in many of the numerous successful cars by Benz during this time, including the legendary Blitzen Benz, the fastest racer in the world at the time. We’re going to stick with his involvement with rear engine cars, as Benz, and after their merger, Mercedes-Benz, were significant players in what led to the Volkswagen.

Early on, Nibel saw the inherent and far-reaching potential in Rumpler’s Tropfenwagen, and persuaded Benz to buy a license for the manufacturing rights in order to develop new cars based on Rumpler’s principles as well as to build some racing cars on these principles as test beds. The first result was the 1923 Benz Tropfenwagen RH (Rennwagen Heckmotor), in essence the first modern mid-rear engine racing car.

Nibel made a number of detail changes to Rumpler’s rear suspension and transaxle, including the use of inboard brakes. Although under-powered with its 65 hp DOHC six, two of them made a fine showing on their maiden outing at Monza, and they left a deep impression on all who saw them. That included Ferdinand Porsche and Adolf Hitler, who first briefly met at a race in 1925 where they both saw the Benz Tropfenwagen racers.

After Mercedes and Benz merged in 1926, Nibel had to work under Porsche, who was then Mercedes’ Technical Director. Porsche at the time felt that his line of famous supercharged 200 hp SSK/SSKL front engine racers were still inherently superior, and the little Tropfenwagen racers were abandoned.

It makes me wonder if Harry Miller’s brilliant 1926 FWD Indy racer was inspired by the Benz RH, given that its drive train configuration is essentially the same but turned 180 degrees, thereby driving the front wheels. The key benefit was the same in both: no drive shaft, so as to allow the driver to sit much lower and thus reduce aerodynamic drag. In Indy oval racing, FWD was not at all a disadvantage, as traction was not critical due to running starts and constant high speeds.

After Porsche left Mercedes, he took up the concept with a vengeance, and secured funding from Hitler for the series of brilliant and formidable Auto Union GP cars starting with this Type A in 1934. They were the first mid engine racing cars to win repeatedly, and left an even longer lasting impression on the eventual format of all GP racing cars, some twenty years later. Rumpler was the father of an enduring concept, to this day.

Already in 1927, Nibel was given the go-ahead to develop small rear-engine cars. The first was this 120 prototype from 1931. It was advanced all-round, with a central tube frame, independent suspension and an air-cooled flat four engine in back. Although not put into production, this is as much as a progenitor to the actual Volkswagen (or Tatra) as anything, given that in 1931, neither Porsche or Ledwinka had actually built something remotely comparable.

Apparently there were issues with the air cooled four, as the next evolution, the 130 had a 1.3 L water cooled inline four at the rear. That would turn out to be a fateful decision, as an air-cooled boxer four is inherently much lighter and shorter, critical in the case of rear engine. The 130 went into low-volume production in 1934,

We can see that the front suspension used two transverse leaf springs. Ganz was consulting with Benz at this time, so that may reflect his involvement, although others had used it before. The rear swing axles had coil springs. The obvious issue with this and subsequent other rear engine Mercedes were that they were excessively tail heavy due to their long and heavy inline water-cooled cast iron engines. Ride over the poor surfaces common at the time was superior to the conventional smaller Mercedes models, and at the low-moderate speeds of the time, handling was considered adequate. But at the limits it was capable of doing what every excessively tail-heavy swing axle car could do, and that was neither pleasant nor safe.

In the 150H sports car of 1934, Nibel reverted to the mid-rear engine format, essentially an update of the Benz Tropfenwagen racer. It used many 130H chassis components, and its drive train flipped 180 degrees, as well as an enlarged and more powerful SOHC engine. As such, it was the first production mid-engine sports car.

More intriguing was the 150H Coupe, which won several long-distance road races in 1934, and looks more than a bit like a somewhat cut-down Volkswagen.

Mercedes’s final rear engine car was the 170H (“H” for “Heck”, meaning rear), which replaced the 130 in 1936. It was introduced at the same time as the traditional front engine 170V (V for “Vorn” or Front), so as to provide consumers the option of two different formats with the same basic engine.

Unsurprisingly, the traditional 170V trounced the 170H in sales, thanks to a bigger trunk, no tricky handling at the limit, and perhaps most importantly, its traditional large upright Mercedes radiator grille on a long hood in front. Mercedes buyers tended to be conservative. The fact that the 170H was considerably more expensive was the final coffin nail, and the plug was pulled in 1939.

That ended Mercedes’ unhappy experiment with rear engines, although it would yet play a role in the development of the Volkswagen, in part due to its experience in building small numbers of rear engine cars like the 150H.

Part 6: Hans Ledwinka – Innovator or Copycat?

Hans Ledwinka, born in Klosterneuburg, Austria in 1878, played a complicated role in the genetics of the Volkswagen. Ledwinka was a brilliant engineer credited with many innovations, and I have sung his praises here at CC. If the tone of this chapter comes across a bit negative, it’s only because it’s been quite fashionable for some time to attribute more to Ledwinka than is justified on the facts. In particular, it’s all too common to come across claims that the Volkswagen was simply a copy-cat Tatra.

Tatra did go to court over patent infringement by Volkswagen, and eventually won a judgement in their favor well after the war, and VW paid Tatra damages (details further down). This alone, as well as certain obvious visual and technical similarities between the Beetle and the Tatras has been used repeatedly to reinforce that the myth that Porsche essentially ripped off Ledwinka, and used the protection of Hitler to do so.

It’s actually a lot more complicated (or not) than that, and I’m going to focus on primarily those issues here. But for what it’s worth, Ledwinka was no stranger to using others’ ideas and designs too.

We’ll skip over Ledwinka’s early years at Nesselsdorfer, where as an 18 year old he joined Edmund Rumpler in designing some less than stellar early horseless carriages, as well his much more successful S4 and S6 cars of the teens. After a stint with Steyr, Ledwinka returned to Nesselsdorfer to design a light, small, and relatively affordable car, one that would be his first enduring and perhaps his greatest masterpiece, the first to bear the name Tatra, the T11. It was designed between 1921 and 1922, and went into production in 1923.

It was a highly successful and quite advanced synthesis of several existing components: a central tube, that would serve both as the frame of the car as well as enclosing the drive shaft. Affixed rigidly at the rear there was the differential housing, from which emanated the swing axles. And attached equally rigidly at the front of the tube was an air cooled boxer twin, over the solid front axle. The engine’s flywheel had vanes and doubled as the cooling fan, whose output was directed to the cylinders via shrouding.

The central tube as a primary carrying member goes back to the 1908 Rover 8 HP, and the swing axles are of course from his former boss, Edmund Rumpler. But the combination was essentially new, and Ledwinka wasted no time patenting all of it, and more, including variations with the engine at the rear, although that was strictly on paper at the time. But that patent, for a rear engine attached to a transaxle, was also used in legal action against Ganz, no less.

The T11 and its successor, the T12, developed a superb reputation for their ruggedness, economy of operation and capabilities. Eventually, Ledwinka added two more cylinders to create the T30, and its evolution, the 57. These were highly capable cars, and Ledwinka’s extensive experience with air-cooled boxer engines made him the world’s leading expert on them, most critically their cooling systems.

Other air cooled engines back then typically just relied on large fins and the passing air over them at speed, or some sort of primitive blower assist. But Ledwinka had been refining the blower and its ducts for years, and as can be seen on this T57 engine, it looks quite advanced and was well proven. Ledwinka patented several variations on the theme of ducted fan air cooling schemes, so general in their scope that there was essentially no way around them. That would include the Volkswagen.

In 1930, Ledwinka’s son Erich started working at Tatra. Along with design engineer Erich Übelacker, they instigated the idea of hanging Tatra’s air cooled twin in the rear of the T57. They already had the right engine for the job, and by 1930, rear engines were the hot new thing. This resulted in the T57 – V570, a cobbled-up two-passenger prototype. According to the definitive book “Tatra – The Legacy of Hans Ledwinka“, this occurred in late 1931.

Meaning after Mercedes had already built its all-new four passenger 120H prototype (left) and by which time Porsche was drawing up his T12 (right).

Ironically, the T57-V570 was unsuccessful, because the air cooling did not work adequately when enclosed in the trunk of the T57’s body, and thus the V570 was abandoned.

Tatra’s second effort was more ambitious, with a new four-passenger body that was developed with aerodynamic input from Paul Jaray. It too used the 854 cc boxer twin. This was the V570 prototype—never developed into a production model—and was completed in early 1933.

Again, that’s one full year after Porsche had built this very similar-looking T12 (1932), for motorcycle maker Zündapp. But Google “Tatra V570 VW” or something similar, and one will find dozens of articles claiming that the Tatra V570 was ripped off by Porsche and that the V570 was the true basis for the Volkswagen. Really?

Of course Porsche was influenced by Ledwinka’s work, to one degree or another, most of all the ducted forced-air cooling. There are other similarities that have been brought as evidence of the borrowing by Porsche from Tatra, such as his early use of twin transverse leaf spring for the front suspension, but that was being done by others well before Ledwinka, including the 1915 Cornelian (Porsche later developed his distinctive twin-trailing arm torsion bar front suspension). There’s the distinctive central backbone/hump in the VW’s platform chassis, but that too was used well before Ledwinka popularized it. And of course the same goes for the swing axle rear suspension.

Ledwinka and Porsche were friends going way back, and often met and discussed their work. As Ledwinka himself said: “Well sometimes Porsche looked over my shoulder and sometimes I looked over his”. Fair enough.

Coinciding with their early efforts at building their first rear engine car, in 1932, Tatra also embraced aerodynamics. We’ve shown that this was hardly new, but the interest in applying it was growing everywhere after Rumpler’s influential Tropfenwagen. Since Tatra had no experience with that, Paul Jaray was paid for the license to apply his principles to Tatra’s cars. Tatra and Ledwinka were aggressive patent filers, and in 1933, they applied for patents in Germany with this application titled “Improvements in or relating to Automobiles.” Take a good look at Fig.3.

Here’s Fig.3 along with another drawing of an extremely similar vehicle (top). Way too similar, actually. What is it?

Here it is, a write up of Tom Tjaarda’s “revolutionary” aerodynamic car in the July 1931 issue of Modern Mechanics, two years earlier. Rear engine, four wheel independent suspension…everything the Tatra streamliner would soon sport, even the dorsal fin.

Here’s Tjaarda with his “Sterkenberg” prototype. He didn’t find a manufacturer in the US willing to take on its further development or manufacture. And we know that Tatra didn’t pay him for using his design as their starting point,as well as in their own patent drawings.

In 1933, Tjaarda went to work for Briggs, the leading builder of all-steel and later unibody car bodies. There he developed this second version, shown at the 1933-1934 Century of Progress exhibition in Chicago.

Ford bought the rights this time, and it was majorly reworked into their 1936 Lincoln Zephyr, using solid axle Model T suspension and with a water cooled flathead V12 engine in front. America was not ready to join the rear-engine independent-suspension revolution.

Not even ten years later, with Tucker’s Torpedo, essentially an updated version of Tjaarda’s concept.

But Tatra was ready to dive in fully and quickly. Work started on the large T77 in 1932, and the prototype was finished in early 1934. It featured a 2.9 L air cooled V8, still looking still quite similar to the Tjaarda protype. It used transverse leaf springs in front, as that was still the most common way to achieve IFS, and in the rear it had quarter elliptic leafs as used by Rumpler.

The T77 was built in limited quantities from 1934 through 1938, and there were many variations in its body details, as this was essentially a hand-built car. Its excellent aerodynamics resulted in the ability to cruise effortlessly at up to 90 mph with only 75 hp. Of course it was expensive too, and as such we’ll leave it for now, and take it up again with Adolf Hitler.

Not surprisingly given its short gestation, the T77 had a number of shortcomings, including some very wicked handling qualities. And it was not suitable for serial production. So in 1936, the definitive Tatra, the T87, arrived; shorter without sacrificing much interior room, better visibility, and handled…a bit less wickedly. It quickly became the favorite of the SS.

And it soon spawned a slightly shorter four cylinder version, the T97, which shared a number of body parts with the T87, but used a 1.75L flat four of 40hp and a top speed of some 80 mph.

The T97 is also often used in the conspiracy theories that it was the true basis of the Volkswagen, that the T97 was blatantly ripped off by Porsche to create the Beetle. By 1936, the Beetle was already on its third version of development, and getting quite close to its final one. Of course there are certain general similarities, but really only to those that think either of these cars were somehow unique. We’ve spent considerable time here showing that none of the features of them was unique, except in some details. And that Porsche started out in this line of development in 1931, a year or two before Tatra.

The T97 conspiracy theory is reinforced by the fact that Hitler did have its production ended in 1938 after he invaded Czechoslovakia. The theory says that he did that because the T97 was too similar to the Volkswagen, and thus would have competed with it. It certainly wasn’t because the T97 would actually present a sales challenge to the coming Volkswagen. The T97 was significantly bigger, a full six-seater, and priced several times higher than the VW’s planned price. And Tatra did not have the facilities to build the T97 or any cars in significant volumes. It was a low-volume producer and the VW was to be built by the millions.

By 1938, all of greater Germany’s economy was controlled increasingly by diktat, as it was in a massive military build up. Tatra, which also built trucks, became a significant military contractor, and it’s more likely that Hitler killed the T97 to make its production facilities available for that. He did keep the T87 in production as it was a favorite of his commanders. Ledwinka would be imprisoned for six years after the war by the new communist regime for war crimes.

As to the lawsuit brought against VW by Tatra, it had three claims of patent infringement: 1.) on the position of the engine (at the rear of the car inline with the transaxle); 2.) the location of the transmission; and 3.) certain details of the VW’s forced air cooling system ducting. Tatra’s patents on air cooling were so numerous that they essentially covered all the bases.

Porsche knew that there was no way not to infringe on the ducted cooling patents, as did Hitler, who told him not to worry about it, that the issue would soon go away. It did, when he invaded Czechoslovakia. But it came back after the war, in 1961, when the Düsseldorf Regional Court ruled that only claim #3 (details of cooling ducts) was valid, and VW made a settlement with Tatra.

After his imprisonment ended, Ledwinka moved to Munich where in his retirement he advocated tirelessly for the principles of swing axles on trucks (as Tatra trucks still use today), in order to improve driver comfort and for improved off-road adhesion. He did not share in the monetary settlement from VW, and refused numerous awards. He passed away in 1967.

It’s rather ironic that Ledwinka is so often identified with the Volkswagen—as its inspiration or ripped-off victim—considering that the well-documented timelines clearly show he was rather late to the rear-engine and streamlined party. And that he borrowed from others to be able to design and build his early streamlined rear engine cars. Presumably it’s because Tatra’s T77 and T87 are just so compelling. They were the first to be produced in any numbers, albeit modest ones, and as such are assumed to be the source of everything that followed in their delicate wake.

Part 7: Ferdinand Porsche – Looking for a Sugar Daddy

What’s there to say about Ferdinand Porsche that hasn’t already been said, so many times? His career started in 1898, when he built the first gas-electric hybrid and then went on to include many of the finest and most successful racing and production cars in Austria and Germany for decades. So we’re going to pick up his story in 1931, after he was made redundant at the Steyr Works due to the Depression. Tired of working for others, at the somewhat advanced age of 56 he started his own firm, Dr. Ing. h.c.F. Porsche Gmbh, offering design and consulting services for engines and motor vehicles. He brought with him a number of loyal subordinates, most of whom had followed along with him at his various previous jobs.

1931 was a difficult time to set out on one’s own, in a struggling economy. He did pick up a few consulting contracts, but he decided that he needed to initiate new projects with the hope of selling them to manufacturers. Given the times, a small car seemed like the obvious direction, and thus the first Porsche-initiated project was called Type 12 “Kleinwagen”, given that number so as to make it look like it wasn’t the first. It was for a compact aerodynamic 4-5 passenger sedan with a rear air-cooled flat four engine.

Motorcycle maker Zündapp bit, and gave Porsche a contract to build three prototypes in 1932. But since Zündapp motorcycle engines were two strokes, they insisted on a two stroke in the T12, and a five cylinder radial one at that. This engine did not pan out, and Zündapp soon abandoned the project. Another factor may well have been the high cost of the all-steel bodies built by Reutter.

But Porsche soon hooked another motorcycle manufacturer, NSU. The project was now T32, and three prototypes were built, with bodies by different coach-builders. The one on top was built by Reutter, as it looked originally (left), and as later modified with lower and integrated headlights (right). That one is in the VW Museum, and is considered by VW as the oldest direct descendant of the Beetle still in existence. The lower left one was presumably built by Dreutz, and the one on the lower right also by Reutter, but to a quite different design and using wood and artificial leather covering.

The Porsche-NSU Type 32 was a bit bigger than the Beetle would end up being, with a 2600mm wheelbase (2400 for the Beetle), and its engine was larger, with 1470cc and 28 hp. The air-cooled boxer four designed by Josef Kales already shows many of the distinctive features that would be used on the definitive VW engine.

NSU also killed the project with Porsche, supposedly because its part-owner Fiat did not want a new competitor. Or because NSU simply found it too expensive and daunting to jump into the car business.

Porsche needed a more substantial and reliable partner for his small car ambitions. He would soon find one; or the other way around.

Along with long-time associate Karl Rabe and backing from Adolf Rosenberger, Porsche also started a subsidiary company to develop a racing car, also on speculation. The “P-Wagen” was essentially an evolution of the Rumpler-based Benz RH Tropfenwagen racer that we looked at earlier.

Initially, there was talk about Zündapp funding the racing program, but that came to naught. Mercedes was the dominant force at the time, and had secured a large grant from the new Nazi regime to dominate the Grand Prix circuit. If Porsche was to get his P-Wagen built, he would also need a more substantial and reliable partner.

Part 8: Adolf Hitler – Car Nut

Hitler with Mercedes leaving Landsberg Prison, 1924

Hitler with Mercedes leaving Landsberg Prison, 1924

For this exercise we’re going to stick to just one or two facets of Hitler’s warped personality. One is that he was a certified car nut. Oddly, he never learned to drive, but that wasn’t uncommon then. During his year-long stay at Landsberg Prison after his failed putsch of 1923, it’s been confirmed that the bulk of the lively daily conversation among Hitler and his coterie of fellow privileged political inmates (and keepers) was not politics, but rather art, theater, opera, and…cars. His loyal friend Jakob Werlin, a Benz employee, fed him with all the latest happenings in the industry and the racing world. And upon his release, Werlin picked him up in a slightly used Mercedes on the cheap, on behalf of the party, meaning Hitler.

One of the books Werlin brought to Hitler in prison was “My Life and Work” by Henry Ford. This would be a deeply influential read, and Hitler evolved right then his plans for putting Germans back to work by building a system of highways to bind the nation closer together as well as mass-manufacturing a small car that the average man could afford. From the day he left Landsberg, automobiles and his grand vision for them was always near the foreground of his thinking, until the war changed his priorities. That’s the other quality: the vision thing.

Hitler’s first major public function after becoming Chancellor of Germany in January 1933—after providentially having become a German citizen in the nick of time—was to open the Berlin Auto Show that February. In his opening address, he laid out his three-pronged vision: highways, cheap cars and international motor racing, to showcase Germany’s technical superiority. And he affirmed that it was the intention of his government to support the production of a Deutschen Volkswagen.

The German word Volk is almost impossible to translate completely and satisfactorily, for there are multiple layers in their meaning. In its most superficial and simplistic meaning, it is just “pertaining to the people”. But it also means “pertaining to a specific culture”, as well as “pertaining to a nationalistic and/or racist movement”. So while the term Volkswagen can mean simply an affordable car, in Hitler’s meaning, it was clearly meant to stand as a symbol of the superiority of the German Volk. It’s why “The People’s Car” as commonly used in reference to the Volkswagen is rather unsatisfactory, at least to me. Volkswagen is a loaded word, or it certainly was so until after the war.

After his opening speech, Hitler made a beeline to the Tatra stand, where he told Ledwinka about how he had used a T11 “for a million kilometers” for his politicking throughout Austria. Ledwinka showed him the chassis for the new T77, and had to go into great detail of its air cooled V8 and rear suspension. That evening Ledwinka was summoned to Hitler’s hotel to hear yet more details. And supposedly Hitler said that any future German Volkswagen “must be like a Tatra—air cooled and robust”. Perhaps this is the basis of the Volkswagen origin myth regarding Tatra and Ledwinka.

One month later, in March 1933, Porsche had his first meeting with Hitler, to make a plea for funding for his P-Wagen racing car. He was told by well-placed sources that Mercedes already had 100% of the funds tied up and that he had no chance of changing Hitler’s mind. But Hitler greeted Porsche warmly, and the two instantly hit it off, thanks to the familiarity of their respective Austrian accents. Porsche was some 15 years older, and became something of a father figure to Hitler, who was in rather desperate need of that. Hitler was always courteous and respectful, to Porsche, who spoke informally and candidly to him, greeting him with “Guten Tag” instead of “Heil, Mein Fūrer!”

Hitler kept Porsche at that meeting for much longer than expected, engrossed in the plans for the P-Wagen. Porsche’s power of persuasion won the day, and he got the funding for his racers. These carried the Auto-Union Silver Arrow name and became legendary in their time, both for their raw power and their tricky handling, which only some drivers, notably Bernd Rosemeyer, ever fully mastered.

In its ultimate 1936 form, Porsche’s supercharged V16 was making over 520 hp and dominated the GP circuits. It was the final feather in Porsche’s very large racing car cap.

The next meeting between the two would be more momentous, and this time Porsche was summoned to Hitler’s hotel room, in May 1934. Hitler was concise and brief: he wanted the Volkswagen built, and he wanted Porsche to head up its development.

During that brief meeting, Hitler sketched his ideas for what a Volkswagen might look like (above).

For what it’s worth, it looks a lot like the Mercedes 130H, which would have just been presented at the 1934 Berlin show. It obviously caught his attention.

There’s also this sketch by him from 1933 that clearly shows a streamliner. It may well have been influenced by the T77, which was new at that prior year’s show.

The basic criteria were spelled out by Hitler: to accommodate four adults and one child, have a top speed of 100 kmh (61 mph) and be able to maintain that continuously on the new autobahn Hitler was having built, and to have a consumption of no more than 7L/100km (33.6 mpg).

Most significantly, he wanted it to be sold for less than 1000 RM (Reichsmark), or some $250 at the time. This struck Porsche as incredible, as constant cost-cutting had driven the cost to build—not sell—the NSU Type 32 down to 2200 marks. Even the little wood and vinyl 12hp Ganz-designed Standard Superior was priced at 1590 RM. Under 1000 RM? That seemed absurd.

But it was not Porsche’s style to question; this was simply going to be his latest challenge, and he would do everything in his power to make it happen. Porsche was apolitical, and one-pointed in pursuing the jobs given to him with his characteristic intensity and thoroughness. During the war years, he never once questioned the practicality or effectiveness of the tanks and other military weapons that he was tasked with by Hitler (most were mediocre or even failures). He stayed above the fray, and just did the best he could given what he had to work with. Initially, that wasn’t much.

In the early 1930s, car ownership in Germany was decidedly still a serious luxury. In 1932, there were only 486,000 licensed cars for a population of some 65 million; a much lower rate than in France and the UK, never mind the US. And even these number are misleading, as a very high percentage of these cars were owned for business purposes.

An analysis showed that the cost of buying and operating a car for 10,000 km per year was 67.76 RM per month, or 35% of the monthly income of a working class family, which were currently spending some 2.3 RM per month for transport (public transport and/or bicycles). The purchase price was too high as was the cost of fuel. Gasoline could well have been drastically cheaper in Germany at the time, due to a global glut of oil during the Depression. But like other European countries, it was taxed high to dampen consumption, since it had to be all imported. Hitler was adamant about Germany developing its synthetic fuel capability (from coal), as he knew that would be essential during a war. That required high prices, as it had to be heavily subsidized. And the taxes were a significant source of vital revenue to the Reich.

Germany’s car industry was very inefficient, with way too many small manufacturers. This was largely the result of Germany’s high import tariffs, which it needed in order to prop up the Reichsmark, the only major global currency that was still on the gold standard during the Depression. It resulted in higher prices than in other European countries; drastically so in relation to the US. Fordism was widely discussed, but not feasible under the circumstances.

Although Ford had a subsidiary in Germany, it was GM’s Opel that was the closest to bringing Fordism into reality. Their small 1.2 L was steadily improved and cost-rationalized, and the 1935 P4 was priced at 1650 RM, which was dropped further to 1450 RM in 1937. The ver conventional P4 was the closest thing there was to an affordable mass-market car, and it had a 50+% share of the market in its class. The P4 was still too expensive for the working class, and the industry was quite wary of Hitler’s vision of drastically expanding motorization. They could not fathom how a legitimate family car could be built for 1000 RM; even 1200 would be a huge stretch.

Still the two biggest domestic manufacturers, Mercedes and Auto-Union decided it was better to take up the effort than have it forced on them later. They jointly funded a development program through the RDA (Automobile Manufacturer’s Association), which signed a contract in June 1934 with Porsche. The contract called for the delivery of three prototypes in ten months.

Porsche had no proper facilities to build prototypes. So the Porsche home garage was turned into a shop, and work commenced…

…from the drawings of the first prototype (Type 60 V1).

The basic elements of the Volkswagen chassis are already all here, except for the plywood floor, which would turn out to be too flexible. Note the different location of the engine cooling blower.

This chassis has a two cylinder boxer, with one carb directly feeding each cylinder. Several different engines were built and tested, including two strokes parallel and boxer twins along with four stroke boxer twins and fours. The challenge was to keep costs down and meet Hitler’s demanding performance and efficiency expectations. This turned out to be harder than initially anticipated.

The finished product was the Type 60 V1 sedan, the first of the direct line of true Volkswagen. These had the flat twin engine.

It was followed by the 1935 V2, a convertible, driven here by Ferry Porsche.

These did not arrive in the stipulated ten months. Porsche was struggling, due to a lack of facilities as well as his masters at the time, the RDA. The primary issue was cost. Porsche’s internal correspondence put the cost at between 1,400 and 1,450 RM, or in other words, about the same as the latest Opel P4. The industry gambled that Porsche, just about the only man in the Reich who could speak frankly with Hitler, would be able to talk him out of his unrealistic price target. But they grossly underestimated Hitler’s absolute determination, and Porsche could see it wasn’t worth even trying.

So the relationship between Porsche and the RDA unraveled, with Porsche essentially bypassing them and working more directly with Hitler. Porsche invited Hitler to a road test in January 1936, without the RDA present. The RDA then responded with a report saying that the cost would be 1600 RM. Expecting to get Porsche into hot water, the opposite happened: Hitler vented his fury at the industry, accusing them of succumbing to elitist thinking. He simply refused to accept that the industry of superior Germany could not build such a car for his stated price.

Hitler assured Porsche that the Volkswagen would be built for such a price, no matter what it took, even compulsory reductions in the price of raw materials and such. And after a satisfactory demonstration of the prototypes for Hitler at Obersalzberg in July, 1936, Hitler decided definitively that Porsche’s car would be built, and not by any of the existing manufacturers, but in a completely new factory. And although the industry was wary of the potential competition, for the time being, they were relieved to be unburdened by Hitler’s unrealistic demands.

The very big question was how to finance such a huge new factory. The solution was the DAF (German Labor Front), which had taken over from all existing labor unions after Hitler took power. Membership was compulsory, and that created a massive influx of funds. It would allow the factory to have not-for-profit status thus avoiding taxes and lowering its cost. And it would limit competition to the existing industry as the cars would be sold to blue collar RDA members. The RDA’s leisure and recreation arm, renamed KDF in 1938, enthusiastically took on this parentage of the Volkswagen.

But even the RDA struggled to finance what was now becoming the world’s biggest automobile factory. They had to sell property and take out bank loans. Phase 1 had a planned annual capacity of 450k cars. In its third and final phase 3, annual capacity was to be a staggering 1.5 million cars, more than Henry Ford’s River Rouge factory, the biggest in the world, and substantially greater than the total sum of all existing German production facilities. Hitler’s expansive vision was mind-boggling.

Development of the Volkswagen continued, with the V3 (left), seen here at the Porsche Villa, with V1 (right). It now had a proper steel floor and a body much closer to the final one.

The biggest change was a brand new engine design. The various two-cylinder engines proved to not be up to the task, so Porsche engineer Franz Reimspiess was tasked with designing a new boxer four. Anyone familiar with the VW engines will recognize this, although it hadn’t yet sprouted the oil cooler on its case. Little did he know what an iconic engine he designed, built in endless permutations by the tens of millions, and still being built today (but not by VW).

The V3 having proved itself, the next step was a series of 30 cars (VW30) built by Mercedes, who had the facilities to do so. This body may look a bit retrograde with its smaller rear side windows, but it was actually a major step forward technologically. Unlike the steel-over-wood coachbuilt bodies of the earlier version, this was designed with production in mind. In conjunction with Ambi-Budd, the all-steel body was optimized to be as stiff, light and cheap to manufacture in vast quantities as possible. This resulted in using a lot of fluting (creases), which was a relatively new technology and made the panels much stiffer than if they had been flat or smooth.

These 30 cars were subjected to a grueling one million kilometer test regime. This took place during 1937, and is a key element in why the Beetle emerged as a relatively durable product from the beginning, and was so effective during the war in its Kübelwagen form.

A lot of Porsche’s time was spent not just on the car itself, but on the process of making them by the millions. He and a few associates went to visit Ford’s River Rouge plant in 1937, to see the vaunted Ford process with their own eyes. They were ferried to the plant in a new 1937 Zephyr, and when Porsche noticed the front hinged door, he telegraphed back to Stuttgart with orders to change the Beetle’s door to front hinged too.

And just in the nick of time, as long time Porsche body designer Erwin Komenda was just finalizing the Volkswagen’s definitive body. These are the wood body bucks, from which the tooling was to be made. The front fenders were yet to be changed to accommodate smoother flush head lights.

I originally intended to include Komenda in the group picture at the top, as he is solely responsible for the Beetle’s body design, as well as many other Porsche creations, including the seminal Porsche 356. Contrary to what some might assume, Porsche relied on a staff to execute his projects, from the first drawings to the last bolt. He was well known to regularly burst into the drafting room or shops and offer highly un-filtered feedback, but he was also lavish with his praise too. Many of his staff spent their entire working lives following Porsche loyally from one company to another, and finally to his own firm.

The first three definitive versions (VW38), sedan, cabriolet and sunroof sedan were presented at the cornerstone ceremony for the new KDF factory in Fallersleben (later changed to Wolfsburg).

At the end of that ceremony, Hitler got in the back seat of the convertible and Porsche drove him to the train station, where his personal train was waiting.

44 of these VW38 pre-production cars were built, followed by 50 VW39 cars in 1939. The 996cc boxer four made 23.5 PS (25 hp), and met the specifications for performance and economy that Hitler had laid out.

One of the key financing techniques for the new factory was that the KDF Wagen was sold strictly on a lay-away plan. The KDF-Wagen Spar Karte (saving card) was launched on 1. August 1938. Subscriber would pay at least RM.5 a week towards the value of the car. They could pay more if they could afford and wanted to. Massive advertising campaigns followed and by the end of 1939 260,000 people joined. By May 1945 700,000 joined in total and 336,000 completed their full payment. Their payments were honored some years later by VW after the war.

In Hitler’s vision, soon his beloved German working class would be mobile, enjoying the freedoms that only the automobile afforded.

The vast factory was built, but of course just as Beetle production was about to commence in 1939, Hitler invaded Poland, and that changed everything.

The unanswered question is how would things have turned out if Hitler hadn’t gone to war? Would the Volkswagen factory have churned out millions of KDF Wagen to enthusiastic buyers? How would it have worked out given the unrealistically low selling price. We’ll never know the answer to the first one, but there’s no reason to think the 995 RM price wouldn’t have been maintained, given Hitler’s adamant dictates on the matter. And it’s reasonable to assume that the Volkswagen Werke would have been able to be at least self-sustaining at that price, for three key reasons:

1.) The factory was fully paid for, and did not have to be amortized in its sales price. That alone is a significant factor, and of course one that caused considerable fear and anxiety in the rest of the German auto industry. 2.) Porsche did an excellent job of designing the Beetle for mass production. After the war, the labor time to build each one plummeted for a number of years as production was fine tuned. It was almost instantly profitable and fueled VW’s rapid growth. 3.) There were zero selling or marketing costs associated with the KDF Wagen, as it was to be sold directly through the local KDF branch offices. Service was to be provided by authorized facilities.

Conclusion:

the proud parents with their baby

the proud parents with their baby

Although there was a lot of DNA in the Beetle from many individuals and various sources going back to Rumpler’s 1903 swing axle patent, there’s no question that Adolf Hitler was the real father of the Volkswagen. The idea of an affordable car for the masses was essentially universal; Henry Ford wasn’t the first to think of that; he just figured out how to make it a reality. The same was the case in Europe, except that after Ford, it became something of a universal desire. And it was acted upon, starting in the teens, to varying degrees, although certainly not highly fulfilling ones.

Having read Ford’s book and given Hitler’s fundamental quest to elevate the German Volk above all others, he made it one of his key domestic priorities, to prove that German superiority could create a factory larger than Ford’s and a car more affordable. He made it happen; the Volkswagen is his baby.

And it’s the only one of his many crazy and demented visions that lasted and flourished after the war (save for some extremists). And today his baby has grown into the largest automobile maker in the world. Now that’s something even Hitler’s megalomania probably never envisioned.

And as to Ferdinand Porsche, he was Hitler’s chosen vessel to bear forth his baby. The willing mother of the Volkswagen, in other words.

Postscript: there’s a lot more detail about the years of the Beetle’s gestation and birth that are fascinating, at least to me, and perhaps we’ll take that up another time. But I have taken on the chapter of the Beetle’s rebirth after the war here: Curbside Classic: 1946 Volkswagen – The Beetle Climbs Out of the Rubble.

The next chapter is here: Curbside Classic: 1957 Volkswagen – The Beetle Takes America By Sturm

And there’s a number of other VW articles in the European Brands Portal in the CC Archives

So the Autobahn and the Beetle were two parts of the same system, just as the record and the phonograph or the Web and the computer.

Streamlining isn’t needed for city cars or farm cars. It starts to make a difference at 40MPH and makes all the difference at 60. The Autobahn was meant to run at 60, which meant streamlining was necessary for the automotive part of the system.

Actually air resistance is a factor at all speeds, just disproportionally greater as speeds increase. Go walk into a steady 20 or 30 mph wind, and you’ll see what I mean.

True, but it’s not until 40/50 mph where air resistance becomes the main source of wasted energy.

Prior to that drivetrain losses make up more

However an EV produces fewer drivetrain losses so aero is more important. Hence aero wheels on a Tesla that you’re unlikely to see on an ICE vehicle.

But it does require energy, more energy than just overcoming frictional losses, from very low speeds already. A more aerodynamic car will be more efficient at 30 mph than a less aerodynamic car, all other things being equal. But yes, the effect becomes greater at higher speeds.

With the very low power engines of the times, aerodynamics was a more significant factor, especially in attaining higher speeds.

Another well-researched and logical article by Paul.

Hervorragend! Comprehensive, yet very to the point and enlightening. Lots of information I didn’t know about. Thanks!

Absolutely fascinating article, being read while I watch today’s Formula 1 race in the background. Glad that someone finally covered the entire chronology in reasonable detail.

Looking forward to follow up articles regarding the early post WWII Volkswagen.

I’m a bigger fan of the article than I am the race! It looks like another Hamilton runaway; I wish one other manufacturer could give Mercedes a real run.

Nice work, Paul – I’ve always been merely superficially knowledgeable about the gestation of the Bug, so I learned a lot.

Achh, no spoilers! I’m on the West Coast and just finishing my coffee before watching…

The best race of the weekend turned out to be the Baggers race at the MotoAmerica Superbike Weekend at Laguna Seca. The entire race is on YouTube, you haven’t seen racing until you watch Hayden Gilliam’s sliding a Harley Street Glide into the curves like it’s a 1000cc sport bike.

Absolutely fantastic read!

I would suggest a nuance to the proposition that Hitler was the Father of the Volkswagen, in that, while there is a definite parallel to Ford’s vision of mass-produced vehicles that ‘everyman’ could own, Ford was also the force behind the design and manufacture of the Model T. His vision was realized by one person, in other words.

Hitler had not the capability to design the product and manufacturing system and had to rely on a second party (Porsche, although he certainly could have chosen another person/firm) for that aspect of bringing the Volkswagen concept to reality. So your caption above, “The proud parents and their baby,” is actually spot on to the nuance I’m suggesting.

A separate question is related to your comment about VW air-cooled engines still being produced today. I was under the impression that production of engines (spares?) stopped in 2006, not long after the Type 1 Beetle ended production in 2003.

Again, excellent article and a real showpiece for CC.

Well, yes, that’s why I made them both parents.

One can still buy brand new air cooled VW engines, just not from VW. 🙂

https://darrylsaircooled.com/

The cheapest one is $4300.

Yikes!

Ed, I’m not sure if this qualifies as “still being produced”, but I’m fairly confident that I could go to any of a number of aircooled VW vendors’ websites and purchase every single component of a VW Type I engine in brand-new condition and assemble one from scratch.

And Paul, I found this a well-written and insightful treatise. As you pointed out early in the article, there are really very few truly new ideas. Most everything that is touted as “new” is just a new combination of existing ideas, and the “Beetle” is no exception to that.

What Hitler did as a dictator was to compel various people to make it happen. My main takeaway from this post, and the truly new piece of information that I gained from it, was that most of the startup and overhead costs were separated from the production costs. Perhaps that’s just a trick of accounting, but it seems easy to build a car cheaply and profitably if one does not have to factor startup and overhead costs into the profitability figures. If Henry ford had been “given” his production facilities for free by the government, the final pricing of the Model T might have been $150!

If Henry ford had been “given” his production facilities for free by the government, the final pricing of the Model T might have been $150!

Given the massive profits Ford was banking from the T, he probably could have sold it starting at $150. 🙂

Your point is valid of course. But there are certain fundamental differences between the US in the 1920s and Germany in the 1930s that make direct comparisons difficult. And the VW was a more complex and sophisticated car, with a modern all steel body.

Although a T two-passenger roadster was priced at $260 in 1926, the enclosed sedan cost $660 dollars, almost three times as much. And a Ford two door sedan still cost that much in 1939. So one really needs to compare the sedan to the $250 Volkswagen.

I’m not so sure that “free” factories would have impacted the T’s price so much. Volume was so high, staggering, that per-unit cost amortization of even the most significant investments might be surpringly little.

For example, using rough figures, if some investment of say15 million dollars was amortized over the T’s entire run, it’d only be about one dollar per unit.

It’s my guess, but wasn’t the entire Highland Park plant probably launched for well south of 5 million?

I don’t have the figures readily available. But yes, my conjecture is that the investment in Highland Park was quite modest in relation to the gusher of cash it produced. Profit margins typically were much higher then. GM assumed a 30% profit margin as a minimum on any program.

It’s like it was once upon a time in the PC business. And how it still is in the iphone business.

Car companies are very happy to hit a 10% profit nowadays.

You’re correct, Evan, in that there’s still widespread parts support for the VW air cooled engines. My point was that VW is no longer producing finished engines nor spares. Darryl’s (and likely others) are building up “zero time” engines from what has to be a combination of NOS and aftermarket components, and in fact, the Darryl’s web site has a buried “small print” statement that some parts are NLA as ‘new’ and refurbished used parts will be substituted in those cases.

You can if you so desire buy an entire reproduction 23 window van its a convoluted system getting the roof panel window holes pressed but it can be done the entire vehicle can be sourced aftermarket so all you have to find is an existing vin some spot welds and hey presto one valueable VW van.

Fantastic read tying all the various parties together. As you said there are numerous outlets offering one aspect or another but I haven’t come across (or looked for, to be truthful) one that takes it in all these different directions.

Most interesting that the shape is representative of (and demonstrated by) numerous different parties working using the same general knowledge set and that it’s really less of a “designed” shape than a natural shape.

An excellent way to start my Sunday, a strong cup of coffee and this comprehensive treatise. Thanks Paul! I knew about bits and pieces of this, but all together, it makes a cohesive story. New, and surprising to me, was that the terms “volkswagen” and “kafer” were in common use long before being applied to the VW Beetle. A couple of other observations: as the owner for ten years of a Ford truck with Twin Traction Beam front suspension, I can see the benefits of swing axles, though they have some flaws in a steering application. And after seeing all the backbone chassis, I think Colin Chapman too was influenced by this school of European design. Finally, I suspect that to Americans, even car enthusiasts whose knowledge of history may have been limited by difficult access to books in the pre-Internet days, the Beetle’s shape and technology really seemed unique. So without knowing the context and environment of the time in Europe, we assumed it sprang fully formed from one person’s mind.

Paul, thank you! You got my Sunday good start by keeping me away from the news as I had my coffee. I’ll sleep better tonight because of that!

The intertwining of tech with the people that create it and the conditions of the time is so interesting.

Quite an interesting Sunday morning read – two cups of coffee!. I knew about some of the original concepts behind the VW and the people involved (Porsche, Ledwinka, Kommenda) but your article went much more in depth and ties them all together very well.

What a fabulous read! Your research into this topic shows clearly. You prove what everyone tends to forget – history is complicated. Every idea is born in a stew of other ideas. Our natural tendency to look for a linear story often obscures much of what was happening all around the central narrative.