(first posted 4/24/2017, updated and expanded over the years. Much to my surprise, this article is often the top non-paid Google search result for JC Whitney. I am humbled and honored to be able to contribute my small experiences to the JC Whitney legacy.)

Regular readers of my Cars of a Lifetime series will know by now that I spent some time working for JC Whitney at the corporate headquarters in Chicago. Given how deeply this brand is ingrained with US car culture, I figured I would share my unique insider’s perspective on the company, especially in its final years.

While I normally dislike quoting Wikipedia in my posts, I will take some liberties here, since part of the Wikipedia article on JC Whitney was authored by yours truly. JC Whitney began as a scrap metal yard on Chicago’s south side, formed by Lithuanian immigrant Israel Warshawsky, who came to the US to escape religious persecution. Warshawsky named the company JC Whitney in order to give the company a less foreign-sounding name.

While Israel did alright for himself, things really started to pick up when his son Roy Warshawsky joined the business in 1934. Possibly inspired by the success of fellow Chicago mail-order giant Sears and Roebuck, it was Roy’s idea to expand the business beyond Chicago by entering the burgeoning mail-order catalog business.

Initially, he started promoting the business with classified ads in magazines like Popular Science and Popular Mechanics. Many of these ads are available in the magazine archives at Google Books, which I’ve sprinkled throughout my post.

The business really hit its stride in the 1950s. The ads eventually blossomed from 4 liners in the classified section to full-page spreads. With the widespread distribution of its now iconic catalog, JC Whitney was well on its way to becoming an institution.

Ah, the JC Whitney catalog: The pulp paper, the dense pages with tiny print, the minimalist line drawings. It is an interesting window into the automotive zeitgeist of the 1950s and 1960s. These decades marked the heyday of JC Whitney.

At the time, JC Whitney still sold a lot of what we would later call “hard parts.” These are typically replacement items like alternators, brakes, body panels, and even complete engines, as shown in the ad above. Almost always made of steel or iron, hard parts are expensive to ship, and have a relatively low profit margin.

But of course, it is not the hard parts that made JC Whitney famous, but rather all those wild, wacky accessories. Unlike hard parts, accessories are cheap to make, buy, and ship, and in later years were manufactured inexpensively in China. Some of our most profitable accessories had gross selling margins upwards of 50%, and sometimes more.

Whether these gimmicks worked or not was almost beside the point. I’m sure deep down not many people expected paint on whitewalls to look as good and last as long as the real thing. They were selling the dream that Joe Lunchpail could have whitewall tires just like his snooty neighbors.

Whenever manufacturers added new styling, technology, or safety features, JC Whitney was always right behind to give wannabes in older rides the new car look, whether it is the 1958-style quad-headlight look for your 1957 car, or a third brakelight for your pre-1986 ride.

With their eclectic product mix and low-budget outré, JC Whitney had something for everyone, and was able to bridge several otherwise non-overlapping automotive subgenres:

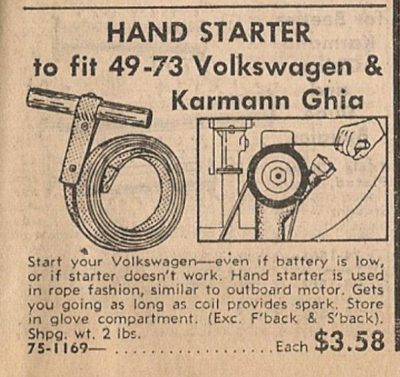

- The hardscrabble, down on their luck kinds, who need to keep their jalopy running with minimal cash outlay. After all, who else would need a VW hand starter?

- Those who wanted to accessorize their car with styling cues and features of more expensive cars.

- Those who wanted to individualize and customize their cars.

All were welcome under the JC Whitney tent. Income inequality? Not here. At JC Whitney, everyone can have a third brakelight or continental kit on their car.

And so it went, for several decades. By the 1970s, cracks were beginning to show in the facade, as the combined forces of rising gas prices, primitive electronics, and emissions controls began to conspire to make it more difficult for the average owner to work on their car, a trend that continues into the present day. Indeed, while researching this article, I discovered that JC Whitney filed for Chapter XI bankruptcy in 1979, a fact not well-known even to the employees of the company. Obviously, they were able to successfully reorganize their debt, but these were the first hints of trouble.

By the 1980s and 1990s, the lower-margin hard parts began to disappear from the catalogs, replaced by an increasingly chintzy assortment of cheap (but profitable) Chinese-made accessories, as the ad from 1992 above indicates. The tiny print and homespun line art was still there, but many of the products were now useless junk.

Roy Warshawsky retired from the business in 1991 and died in 1997. Roy’s last surviving sister sold the company in 2002 to The Riverside Company, a private equity investment firm. At this point, JC Whitney was no longer a family-owned company, but for the time being, was still Chicago-based. Although details of the transaction were never made public, informed speculation around the office was that the sale was for somewhere around the $60 million figure, for what that the time was a company with $170 million in sales. This was already down from peak sales volumes north of $200MM in the ’90s.

In 2006, Riverside made one last-ditch effort to revitalize the business. Riverside acquired my employer, truck accessory catalog company Stylin Concepts, and shoved us together in a shotgun marriage.

Riverside had correctly identified that the automotive aftermarket business was ripe for consolidation and figured that JC Whitney would be the instrument for that consolidation. Towards that end, they created Whitney Automotive Group as a kind of parent holding company, with an eye toward other acquisitions and brand expansion. Riverside brought in a young, hotshot executive from Dell to boost our eCommerce street cred, and created a new vice-president of M&A (merger and acquisition) position. We moved into fancy new digs on the top floor at the corner of Michigan and Wacker Drive, right at the doorstep of Chicago’s Magnificent Mile. In an effort to give the place a startup vibe, the dress code was relaxed to jeans, and the de rigueur foosball table placed in the lobby along with a video wall.

Roy was long gone by the time I joined the company, but his legacy was everywhere. Portions of his collection of antique gas pump globes and other automobilia still decorated the office, along with pictures of some of the cars from his large personal collection of cars (with a particular fondness for 30’s luxury brands, including a V-16 Cadillac once owned by the King of Denmark). The conference room that housed most of these items was still called “Roy’s Garage.”

We had all kinds of great ideas, many of which were long-term bets that may have eventually paid off had we been able to wait it out. Among them:

- Install Pro – While Whitney long catered to the DIY (Do It Yourself) market, we thought we could carve out a new niche in the DIFM market (Do It For Me). We set up a network of installation shops (similar to what Tire Rack does), where the customer could pay for installation along with the product, and we would ship the parts directly to the installer. A good idea, but we weren’t able to put enough effort into it to assemble a large enough network of installers, nor were we able to market it properly.

- carparts.com – JC Whitney’s business was constantly under assault by what we called “ankle-biters” – small fly-by-night companies with a search engine optimized online storefront and not much else: No inventory (strictly drop ship), no customer service, no catalogs, and (most importantly) none of our fixed costs. Carparts.com was our attempt to create a no-frills website in the same vein that could compete on price with the ankle biters. In exchange for bargain basement prices, it had no phone number and outrageous restocking fees for returns. It also made very little money.

- Sears at the time was trying to fashion itself into an eCommerce portal similar to Amazon, so we entered into a co-marketing agreement where we would create and maintain the auto parts portal on sears.com, and we would handle the fulfillment. In return, it seems, Sears got most of the profits, and we just got some contribution dollars to fixed costs.

- We spent enormous sums of energy looking at many potential business acquisitions, ultimately without consummating a single deal.

Readers of this site will be well familiar with the concept of a flywheel. A similar concept applies to the core business of any company, which in Whitney’s case was its core auto accessory business. A flywheel can take a tremendous amount of effort to get spinning, but once it gets going, momentum will keep it spinning cash with little to no investment for seemingly forever. But alas, flywheels eventually slow down, and so it was with JC Whitney’s. With all these efforts spent towards growing and expanding the business, the core business was withering away due to inattention faster than the new business opportunities were growing.

A funny thing happened on the road to recovery in 2008: The financial collapse that sparked the Great Recession intervened. Credit became non-existent, effectively killing any M&A activity. Worse, we were trying to reposition JC Whitney upmarket (with carparts.com moving in towards the bottom end) at the worst possible time. Remember the companies that were doing well between 2008 and 2010? Low-end consumer companies like McDonald’s and Walmart. With JC Whitney, we had a brand name synonymous with cheapness, and instead of capitalizing on it, we were running away from it.

About that brand: Major companies spend millions of dollars promoting their brand, keeping it top of consumers’ minds. JC Whitney, on the other hand, spent virtually nothing on branding, and as a result, it was quickly becoming an aging brand among the likes of Ovaltine or Prell. People kind of vaguely knew about JC Whitney, but it didn’t really resonate anymore. Indeed, the most common reaction I got from people when I told them I worked at JC Whitney fell into two categories: “My Dad used to buy from you,” and “You guys are still around?” Not the kind of word association you want for your brand.

Over the next few years, the core JC Whitney business continued to founder. Customers continued to age and die out of our mailing list (whose average age was in their 50s). Sales continued to spiral downward to around the $120 million mark, as a whole new generation of buyers who had never heard of JC Whitey went to places like eBay, Amazon, and Google for their parts.

It is said that the only thing harder than managing growth in a business is managing decline. We were shrinking towards being a $100 million business, but we still had the cost structure of a $250 million business. We couldn’t reduce our costs fast enough, so we ended up piling on debt. We were leveraged to the hilt: We borrowed against every asset we had, and had gotten to the point where we were essentially financing the business on the backs of our vendors. As we continued to delay payments to our suppliers, it had gotten to the point where some were refusing to sell us products or extend us any more credit. Everyone knew that the end was near.

At this point (around the summer of 2010), Riverside announced to the world that they were shopping for a buyer for WAG. Our ideal outcome would be an “angel investor” who would be willing to make the necessary investments to revive our moribund brand for the 21st century. Our worst case would be a competitor who would shut us down and strip us of our two main assets – our brand and our customer list.

While we had numerous potential suitors come through our doors (including most of the major brick-and-mortar auto parts resellers), in the end, the outcome was the worst-case scenario I outlined above. Rival competitor US Auto Parts ended up acquiring Whitney Automotive Group (along with all its debts) for $27.5 million on August 17, 2010. I thought this was a good price; more, actually, than I thought what was essentially a break-even business was worth by the time you subtracted all the liabilities.

Once the deal closed, USAP moved quickly to reduce headcount, including the entire WAG executive team. I was one of the lucky ones (along with most of my IT team), who got to spend the next seven or eight months winding down the Cleveland and Chicago offices, and migrating all the JCW systems over to USAP’s platform. I must give credit to US Auto Parts for how they handled the acquisition. I always felt like an active participant in the integration, and not just watching from the sidelines. They handled everything very professionally and made sure I was taken care of with a decent severance package.

US Auto Parts is not the villain of this piece, however. Whitney’s wounds were self-inflicted, and USAP was just there to scoop up the pieces. USAP paid a heavy price for their purchase: Whitney was in much worse shape than the brief discovery period before the sale closed allowed them to fully realize. Their stock has been stagnant for the past seven years, and they are only now returning to profitability.

As I insinuated at the beginning of this article, JC Whitney still exists today, but only as a storefront for US Auto Parts. Other than the name, there is no longer any connection to the Chicago-based company founded by Israel Warshawsky 102 years ago. The Chicago office is long gone, although the distribution center in La Salle still exists, along with the outlet store, they are both owned by US Auto Parts. The general print catalog, which was an enormous marketing expense, is mostly a thing of the past. Only two specialty books still exist, and they are for the largest and most profitable segments: Jeep and Truck. All the other specialty catalogs (Classic VW, Motorcycle, Auto) are long gone.

Postscripts

July 16, 2020: US Auto Parts Network (now rebranded as CarParts.com) announced that it is shutting down the jcwhitney.com website and that it has ceased all print catalog publication. JC Whitney will live on only as a private label brand for some (presumably cheap) CarParts.com auto accessories.

October 2023: Jcwhitney.com is reborn as an automotive lifestyle blog with search engine-friendly content designed to funnel clicks back into carparts.com. While the print catalogs are still gone (likely never to return), they are, somewhat curiously, offering a print magazine for those who still wish to consume JC Whitney in physical form.

Related Reading

Curbside Newsstand: JC Whitney to Cease All Sales

References

https://www.hemmings.com/magazine/hcc/2006/10/Roy-Warshawsky/1351501.html

http://multichannelmerchant.com/news/j-c-whitney-sold-01082002/

JC Whitney supplied many parts for my Little British Cars

Great article! I read that catalog from cover to cover, especially enjoyed the VW page or two since I had a ’63 bug and later a ’66 van/camper.

A fine writeup and a memorable sendoff for a company that loomed large in many lives. Before Amazon, there was JC Whitney, apparently. My own old man has related stories of crap be bought from the JC Whitney catalog. There’s still a little tiny faded and peeling chrome rear-view mirror on a ’76 Ford truck we own that came from his ’56 Plymouth when he was a young man in the 1970’s. Kind of little thing that keeps on trucking down the ages. And seriously, that thing is comically small. People used to put up with a lot back in the day!

What a blast down memory lane! As a bored 9th grader in cowtown Connecticut, I would fantasy-garage my fantasy new car (’71 Plymouth Valiant 2 door in olive green with a 225 and 3 speed..hey I was pragmatic even back then…) with JCW parts (hood ornament, wheel covers, etc). I was always fascinated in how much they carried for the most minute detail item. A few years later I ordered some stuff and it seemed decent quality.

As a kid in the 70s I used to while away my time with the JC Whitney catalog building Baja Bugs and custom vans. I never actually bought anything since by the 80s I was using specialist parts retailers for my water cooled VWs. A college friend did buy an alternator from JCW around 1984 for his garage sale purchase 73 Galaxy 500.

I ordered all kinds of VW parts in the 80s. I even ordered some sunglasses. I thought JC Whitney was great! They still offered a supercharger for a VW as late as the mid 80s. Too bad they couldn’t make it. Of course the backyard mechanic is pretty much gone due to the electronics on modern cars.

Thanks for posting. I have bought from them since 1965. Bought brake shoes, a handful of rivets, and a little press that u hit with a hammer to install the rivets. Bought an all metal ” Wolf Whistle” that ran off vacuum. Bought all the way up to the 90s. Bought a neat little luggage rack for my 97 H.D. I will miss them.

Brock–a luddite in the Ozark Mountains.

Fascinating history of a company that’s been familiar to me since I first fell in love with cars in the 1950s. Today I received an email from JCW informing me that “J.C. Whitney” would henceforth be a brand within CarParts.com – the child becomes father to the man, as has been said.

Closest thing to JC Whitney now is Harbor Freight

Folks can say what they want, But J C Whitney was the place for us guys with little money to get so many things for our cars that we could otherwise not afford. After seeing my friend bake his freshly painted Triumph bike engine parts in the kitchen oven., I decided to order the parts to rebuild my 77 Toyota Corrolla motor. I rebuilt it on the kitchen table. I was only 19 yrs old and the motor came out great…..Lost my gIrlfriend though, but always could depend on J C Whitney and I did. My rear window had that sticker that said ” This car runs on Genuine Junkyard Parts’ Anything new usually came from J. C. W. Poor people still have to get to work out in the country.

R,I,P, J C Whitney …..

I’ve been in and out of JCW for years when they were on 18’th and State.. Once they moved to Lasalle .I never got a chance to visit..

Just the other week I needed a Fender for an 98 gmc pickup..

I called and got some international operator from carparts.com..

I asked about picking up the fender from the front doors at JCW… And was told.. They don’t have a front door anymore.. All drop shipments..

Any and all items from Carparts.com are all drop shipped and there is no parking lot for JC Whitney … I was told this happen early 2020.. Such a shame, I loved that place..

You will forever be missed… 🙁

I remember as a young lad ,going to what I believe was a building in Chicago.it seemed like one end was Warshawsky,and the other jc Whitney same building 🤷🏻♀️Anyhew,I still have jc Whitney catalogs ,and have bought numerous parts over the years !! Great story,,and great that America was a great place …Americans should go back to Ellis island ,and remember….that was a starting place ,for great American beginnings!!

I remember ordering some “hard parts” king pins and tie rod and for my recently acquired ‘52 Chevy pickup in 1975. They wear cheap and I was poor. When the parts arrived , each box was wrapped in plain brown paper. Inside the paper was the genuine GM old style black and yellow box. Amazing!! I ordered some weather strips for the doors and they came exactly the same way. Apparently they purchased some discontinued GM stock . I miss the place tho! Still have the truck !!

I remember ordering some “hard parts” king pins and tie rod and for my recently acquired ‘52 Chevy pickup in 1975. They wear cheap and I was poor. When the parts arrived , each box was wrapped in plain brown paper. Inside the paper was the genuine GM old style black and yellow box. Amazing!! I ordered some weather strips for the doors and they came exactly the same way. Apparently they purchased some discontinued GM stock . I miss the place tho! Still have the truck !!

I loved JCW! They had the unique and hard to find items and the prices were good. They were especially good for having parts for outdated cars and trucks.

I shopped JC Whitney from the mid 1980s to the late 2000s, when they fell off my radar. I bought loads of stuff from them over the years, from motorcycle tires to electronics. Most of the stuff was decent quality, and sometimes surprisingly good for the price. I was only disappointed once or twice. The shipping costs were the biggest issue. I would have bought a whole lot more from them if the shipping rates were better. I tended to wait for the rare shipping rate deal. I always had at least one catalog with pages folded so that a corner stuck out marking something I wanted. I was hit hard when they suddenly stopped carrying all the stuff I was interested in. But the Internet stepped in to fill the void…

I’m now getting carparts.com marketing emails with almost the frequency I used to get JC Whitney’s catalogs LOL. I guess that’s what prompted me to search Wikipedia for them to see what happened, and why I came across this article just now. Very interesting, and explains the timing of my loss in interest in JC Whitney.

I have to strongly disagree with the stated reasons for JC Whitney’s decline, though. Marketer and economist B.S. notwithstanding, the reason they failed is because they *did* try to change with the times. All that utter bullshit about branding is nonsense. When they gave up their core business and especially gave up the name, that was the death knell. There’s no chance I will ever buy anything from such a generic name as “carparts.com”, especially now that I know it hasn’t been the same company for years.

And yep, the same is true of Radio Shack. The instant they dropped all the electronic components and started carrying cell phones, they lost me, and the rest of their customer base, completely. Who needs to go to Radio Shack for stuff they can get closer and cheaper elsewhere? I went there for the stuff I couldn’t get at any other brick and mortar store. There was never a Radio Shack near me, either. I had to really want to specifically go there, so once their catalog was the same (actually much smaller) than everybody else’s – but the prices were higher – there was no reason at all for me to ever go there. Radio Shack was for when you started a project and needed some obscure component RIGHT NOW to continue. No waiting for online or mail order to arrive, just make a trip to Radio Shack and keep going. Once that option was closed, Radio Shack lost all relevance.

I had a ’73 Beetle and needed a stereo for it, as it had only a radio blank plat, (original owner ordered a completely BASE model. OK…off to RS.

Go the AM/FM tape deck, amplifier (40 thumpin’ watts!), and speakers from Radio Shack. The speakers were their small bookshelf speakers, and they were very good I used them for about 20 years at home after I sold the car.

I just found this site and I wanted to share something with this thread. My parents had a coffee shop in the Warshawsky building at 1104 So Wabash. The catalogue was produced at the office in the building. Roy would come into the coffee shop and would not allow vending machines in the building in order to drive employees into the coffee shop. I learned short order cooking and the cash register. Coffee was 10 cents. Boston 12 cents. It was a great time for my family. I could see the Essex Hotel across the street and saw the Beatles swimming at the pool!!!!

If not already mentioned, it does appear as of this writing (10/07/21) that there is a phishing site trying to capitalize on people like me who go looking for JC Whitney, not yet knowing the history as outlined in this great piece. The phishing site is jcwhiteyonline dot com, and attempting to navigate to that brings up a redirect to www dot kqzyfj dot com with all kinds of browser and AV warnings. Beware.

Great article Tom! It brought back many fond memories. I used to browse the JCW/W catalog in high school study hall. If I recall there was even a copy in the library. To be fair I think that aftermarket accessories from just about any store were junk back then. Whitney/Warshawsky hard parts were decent quality and often items no one else could supply.

Through the years I bought many, many things from them, Honda motorcycle engine gaskets, seat covers for a ’71 Suzuki pickup truck? An alternator for a Peugeot turbo diesel? ’50 Ford kingpin bushing kit? Sure! Motorcycle tires, car and bike exhausts. My first car was a $20,’63 PontiacTempest and I rebuilt the engine with JCW/W parts.

As a side note, everyone’s first car should be basic and bare bones. We learn how to make repairs when things go (or are when purchased) wrong, not to mention driving a 4 cylinder 3-speed with no power assists. An oil filter was an option it didn’t have which is why the engine needed rebuilding but it did have an AM radio and a heater.

That store were close enough that myself or a buddy could make the 20 mile trip to the big city if we couldn’t wait. Which was an event in itself. It was always busy and we had to take a number and wait to be called. Sometimes we had to go to the Throop Street warehouse and wait some more. At least if you went in person you could check the parts ahead of time, many times I received the incorrect part through the mail.

I still have some of the “free gifts” (plastic boxes and a spotlight) from those mail orders. Still have a couple free Radio Shack flashlights too.

It was one thing to buy products mail order from the JCW catalog, but I also had the pleasure of picking up a AM FM radio from the Archer avenue headquarters in Chicago in the summer of 1971. I remember it being extremely busy, and the ladies working the counter knew what they were doing, and were not about to take any nonsense from anyone. The floors were planks of well-aged oak that creaked as you walked on them and contributed to an overall feeling of a busy and well run business.

I think I recall buying an electronic ignition conversion for like 9 dollars. It worked for like a week on an old Maverick.

I owned a 1962 Fiat 1200 Cabriolet in the mid to late 70’s. Fiat dealers wanted nothing to do with it and any part you sweet talked them into ordering took 2-3 months to arrive from Italy. It had a granny gear 1st gear and I got too quick on my downshift once and blew a tooth off the cluster gear. New gear from Fiat of Italy -$95 in 1977 and I ordered it July 5th, it arrived December 24th. For every day stuff like tune up parts, gasket sets, brake shoes ,etc, JC Whitney was my go to place. Thanks to them I kept it running and on the road for a decade and a half. I retired it in 1987 after a tree fell on it and by that time even JC Whitney was dropping parts support for it. Now with the internet, I could buy any part I wanted for that car without spending hours on the phone or multiple letters it Italy.

I found several JCW catalogs in some stuff that came from my Dad’s shop when he passed in 2013. I am still sorting through stuff and just fonud these a couple of weeks ago.

I was there until the bitter end. My position was eliminated via a phone call from a lawyer in California. You forgot one thing in the story, the moving of a guy who was responsible for the death of Blockbuster coming on board

https://www.digitalcommerce360.com/2007/10/15/blockbuster-online-chief-leaves-to-head-up-u-s-auto-parts-netwo/

My wife had a VW starter rope (home made) in college in the early 70’s. She also became knowledgeable about parking on a grade for easy coasting starts.

It was the right time backtheeeen

, It rockedd

I spent many hours reading through the catalogs wishing I could afford a one-piece fiberglass front clip or many of the other speed items. I ordered a lot through them in the 70s. Always wanted one of those jester hood ornaments (guy thumbing his nose) but wouldn’t have had the nerve to put it on my car. Same with Hemmings Motor News which was like a small city phone book.

I’m with you Jeff ;

I still have the Aermore exhaust whistle I bought forty years ago, I never did use it and don’t regret spending the lolly on it .

I too wanted to get that silly ‘Jester’ ornament, I wonder how many they sold that were never installed .

-Nate

“Bed Bath & Beyond” crashing all the way down now.

I used to listen to NPR’s “Car Talk” religiously back when it was on the air. I remember one caller who wanted to install an air horn in his car because he thought his car’s horn sounded too puny. Click and Clack spent some time discussing how one might do this, and then one of the brothers had an epiphany. “I know who has what you need! J.C. Whitney!” Seeing that “ocean line blast horn” ad made me immediately remember that call, and confirmed that he was right.

It was always fun to add up the fuel savings all the various miracle spark plugs, fuel magnets, air-bypass valves, high-output coils, fire-ring spark plugs, free-flow air filters, foam injectors, ect, that were advertised in the catalog- it would add up to well over 150% savings! The shop joke was that if you installed all these things, you would have to bring any empty gas can with you and stop every 20 miles to drain a gallon or two out of the gas tank to keep it from overflowing.

Interestingly, those gapless flat faced spark plugs were a real boon to older engines that burned lots of oil and blew blue smoke, they didn’t foul .

-Nate

As a kid in the 60s, JC Whitney catalogs were fascinating for my friends and I. Not even really car kids, just kids. 70s and 80s I did buy a few things from them, they were the only place I could find that carried tie rod ends for a Simca I had at the time. Not a bunch of stuff, but some. Doubt they made any actual return as many catalogs as they sent me, but they weren’t a total loss either. Seems like quality was hit and miss, mostly you got what you paid for, if you paid for junk, that’s what you got.

Even if it had been perfectly run I don’t see how it would have survived the internet age.

Cleaning out my father-in-law’s garage last summer, I came upon several large cardboard boxes of steel and rubber car parts. A little sleuthing revealed they were body and gasketry items for his long-departed Karmann Ghia. As with most of the other repair jobs around his house, he’d bought the parts but never installed them. I’ve also got the catalogs that came in the boxes, which date back to 1985. They’re fun reading.

I had a 72 Chevy Impala that had a Winky the cat in the back deck/ window and those glue on extra tail lights just outside the window.

I represent an entirely different perspective of JC Whitney or, more specifically, probably Roy Warshawsky. I was the manager of finance and administration for the San Jose Graphics division of the then Arcata National Corp. (subsequently renamed Arcata Corp). San Jose Graphics printed – utilizing very, old fully depreciated letter press equipment, the JC Whitney/Warshawsky catalogs. Tho I remember the catalogs well during the 1960’s since I was a “motor head”, what I’m writing has nothing to do with the content of the catalogs.

In approximately 1978, I had constructed a new printing contract for Warshawsky which was a much better price structure than had ever been proposed since it covered only direct costs; labor and material, and all the plant overhead…the fixed costs normally allocated to the pricing structure for a client’s contract production had already been covered by existing contracts for other customers.

This was a win-win deal for both Arcata…it utilized equipment that was planned for elimination and Warshawsy got better per unit production prices.

So a bunch of Arcata VPs, managers (I was not one of them) and the Group CEO flew to Chicago to meet with Roy and the Warshawsky management team and present them with the new contract terms.

Roy and his team walked into the conference room….and slapped Arcata with a lawsuit. I don’t remember the basis of the suit but, as you would expect, the Arcata team stood up and walked out of the meeting. That immediately ended a many year relationship with JC Whitney/Warshawsky. I do not know the outcome of the suit but I’m reasonably sure Aracta successfully defended the suit.

That event may have already have been an early indication of the forthcoming bankruptcy of Warshawsky and company.

Mr. Baker, that is approximately when I lost several hundred dollars to JCW. I had ordered items needed to rebuild a ’65 Cadillac hearse. I received very few parts and eventually not one dime of the money they owed me.

I was so disappointed. I just could not believe after looking through these catalogs for at least a couple years, JCW would not follow through.

I was 17, I’m now 62. I came here from a search on the phrase “how many times since 1975 has JCW filed for bankruptcy”. No, I’m not still hot about the screwing. Not at all. I only worked 2 years in the hay field for a quarter an hour to buy those parts.

I loved poring though the catalog even though I grew up Old Order Amish driving a horse and buggy. We were not supposed to have horns on our buggies, but as a teenager I ordered an Ah-oo-gah horn from J.C. Whitney, installed it under my buggy and had a lot of fun with it. I suspect I still have it around here somewhere. I should find it and install it on my Ford F250 because I think the horn sounds wimpy for the size of the truck.

And about Radio Shack, I drove my buggy to the mall, bought a combo 8-track/cassette player and speakers for my buggy. Once it was all installed and functional I went back and showed it to the R.S. guys. They loved it. No, we certainly weren’t supposed to have that either!

I am looking to connect w descendants of the Warshawsky family. Ideas?

Roy’s daughter, Carol Warshawsky Steinberg, is on the board of the Newberry Library in Chicago. Probably resumed her maiden name. Shouldn’t be hard to find.

Great article!! The first catalog I ever received (around 1972) was from Warshawsky & Co. The checks they cashed had “W & Co” as an endorsement. Later I found an identical catalog with JC Whitney. The last thing I ordered from them was headers for a ’75 Chevy pickup big block, probably around 1993. I still have the truck with the headers!!!

JCWhitney is BACK! Check it out at JCWhitney.com

I worked in Lasalle in the call center from 96 to 07. I was in special orders from 00 to when I left. I remember when Roy’s widow sold the company. She didn’t want the hassle of a multimillion dollar business to be fought over after her passing. So she liquidated everything. When Riverside came in first thing they did was clean house with employees then sold off decor and props throughout the building. Jc Whitney had contracts with 3rd party companies that paid the phone bill in exchange for solicitations after placing orders. One of the biggest down falls I experienced was poor management. They hired people that knew nothing of the automotive industry or the products that they sold.

OMG! I’m not sure how I found this site. OUTSTANDING! I worked at Warshawski’s on the corner of Archer and State during the summers of my college years. I started in the catalog department on the second floor and was promoted to the parts sales floor. What a place. I think the motto was “We have part for every car ever made since 1918” or something to that effect. We have quite a crew there. I would take the Archer #62 from Throop Street and it would drop me off right in front of the store. There were lines wrapped around the corner to get in every Saturday morning. It sounds like the “Fall of the Roman Empire.” Life comes full circle, I’ve been writing for the Auto Collision Industry for the last 18 years. I am forever grateful for having been able to work those summers. My parents were happy too. Batteries and Starters are very heavy.

Thank you Roy Warshawsky.

Remember the catalogs came every two weeks or so. Bought a set of sisal floor and trunk mats for my Moms 1989 Nissan Stanza. Cost $100 at the time. Best mats I have ever seen. Never faded or wore. Closest thing now days costs $400. Thank you JCW.

I decked out my ’87 F250 in ’95 with Dual Air Horns, Power Window & Door Lock Kits, Tailgate Handle Lock, Panoramic Rear view Mirror. Everything still works today! Took JCW for granted and now it’s gone. Really miss perusing the catalogue just for fun. I’m going to go get one off eBay right now!

Hi, Tom. First of all, this was an interesting read. Thanks so much for putting it together. I am an employee of CarParts, looking through the history of JC Whitney, because they just relaunched the Catalog and added merch. I’ll be doing employee trainings and I’m presenting a brief history. Thanks so much for this.

I still remember driving in to Warshawsky’s (or was it J.C.Whitney?) from Rockford when home on leave in the early 70’s. Huge U-shaped counter with many workers. They called your part in thru old-fashioned megaphone tubes/funnels. A short time later, the part would come out of the wall on one of the many conveyor belts. What a time!

Built many cars and trucks through the 70’s and 80’s with JC Whitney. Still have them, and those I sold are still on the road and in collections. Carpet kits, custom exhaust kits, headers, steering/brake components engine rebuild kits….high performance….all top notch components were available, you could set up whatever camshaft, pistons, bearings, you wanted. I’m 68 now and never stoped building cars and trucks. It’s not quite the same anymore, a little more work and much higher prices, more hunting….picking and choosing. Very fond memories dealing with J.C. Whitney.

Very sad indeed, for well over 50 years my father and I purchased more Studebaker parts for our Studes that you can imagine. You know growing old and seeing the death of so many friends and old car repair businesses is difficult to accept.Rest in peace JC.Whitney, like life itself……..it was a good long ride.

I was browsing in my local Books-A-Million store this weekend and found a magazine called J. C. Whitney that has editorial content and a J.C. Whitney catalog included. I didn’t have the time to browse so I plan to go back this week to check it out. I did notice this was labeled Issue No. 4.