The sliding sunroof/moonroof was a seldom-seen feature on cars when I was growing up in the 70s, and second only to air conditioning in terms of the amount of awe and wonder it would generate in me. With the simple push of a button (or occasionally the turn of a crank), you could slide open a steel (or occasionally glass) panel in the roof to let in sunlight and fresh air. Amazing! You get most of the benefits of a convertible, with none of the drawbacks associated with a fabric roof (noise, wear, leaks, and poor security).

Let’s take a look at the history of this device, which extends back much farther than you would likely suspect.

The Pytchley Sliding Roof

The first sunroof appeared not too long after the appearance of the first closed-bodied cars, and in a country not known for its abundant sunshine. In 1925, Noel Mobbs of London was the first to commercialize (and patent) the sliding roof panel using the trade name of “Pytchley.” Early models more closely resembled a sliding hatch than a modern sunroof (as can be seen in the photo above), although later iterations were improved to be flush with the roof when closed.

By 1927, Pytchley had their first customer, Daimler. Interestingly, this Pytchley ad lists Standard, Chrysler, and Sunbeam as customers as well, although in my research I was unable to find any evidence that any of these companies ever sold a car equipped with a Pytchley roof.

In 1932, Morris started licensing the Pytchley mechanism for “sliding head” models of their Minor, Major, and Ten models. Other English manufacturers soon joined in offering the Pytchley roof, with Austin also offering it in 1932 and then followed Wolsoley in 1935.

One manufacturer who opted not to pay license fees to Pytchley was Vauxhall, who introduced their own “Sunshine Roof” in 1937. Vauxhall made numerous design improvements over the Pytchley design, notably that the sliding panel now slid under the roof instead of over it. These differences weren’t enough to stop Pytchley from suing Vauxhall, and on April 8, 1941, British courts agreed ordered Vauxhall to pay damages.

The sliding roof would remain a pre-war British curiosity, as no companies outside the UK produced any vehicles using the Pytchley mechanism that I could find. Pytchley Autocar Company does not appear to have survived World War II. In any case, their numerous sunroof patents began expiring in 1941, which would have greatly limited their ability to earn revenue from licensing.

1937 Nash

Many online sources credit Nash as being the first to introduce a modern sunroof in 1937, based largely on the single photograph above, which is an internet falsehood that I would like to put to rest. For starters, the claim is false prima facie as the Pytchley roof predates the Nash by more than a decade. Furthermore, Other than the single photo above, there is no evidence of Nash actually producing or selling any cars so equipped. The feature is not mentioned in any brochures or period ads, and Google searches for any 1937 Nash equipped with one come up empty.

The experts I consulted at the Nash Car Club of America (NCCA), one of whom owns a 1937 Nash, were unfamiliar with Nash ever offering a sunroof option. The photo above is obviously professionally lit and staged, and judging by the sloppy metalwork it is clearly a one-off, likely created by a third party for publicity purposes – What we would today call a concept car.

1939-40 GM Sunshine Turret Top

From 1939 to 1940, Buick, Oldsmobile, Cadillac, and LaSalle offered a sliding panel roof called the Sunshine Turret Top, perhaps the most cumbersome name ever to grace a sunroof. While it was created in response to the rising popularity of sunroofs in Great Britain at the time, it was not a licensed Pytchley design. Rather, it was developed and patented in-house by Ternstedt Manufacturing Company, a subsidiary of GM’s Fisher Body division. Available only as a special order, they only sold in the hundreds and are exceedingly rare today.

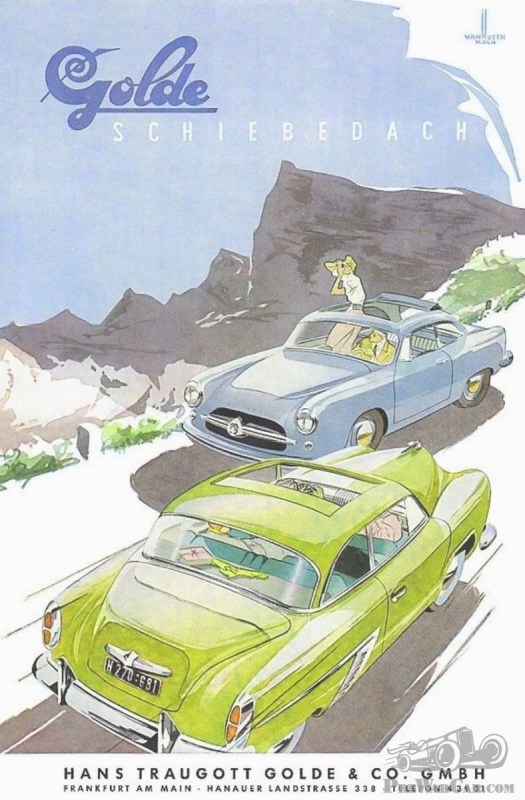

Golde Schiebedächer

The Golde family of Germany has a long history of automotive tops. Traugott Golde, born in 1845 in the central German state of Thuringia, was a blacksmith by trade, and a coachbuilder who founded his eponymous company to make folding carriage tops in 1872. The automobile gave Traugott Golde a whole new market for its folding tops, like the one pictured above. After his death in 1905, Traugott’s sons Richard and Alfred took over the business (while keeping the Traugott Golde name in the company). In 1910, Traugott Golde (the company) founded the “Golde Patent Top Manufacturing Company” in New York to make use of their US patents, where they started making their patent canopy roof for US consumption. This exposure to the United States would come in handy later, as we shall see.

Golde supposedly even independently invented a sliding panel sunroof in 1927, around the same time as Pytchley. However, unlike Pytchley, Golde was unable to convince any manufacturers to equip this feature in their cars at the time (although Golde sold a few as aftermarket items).

After World War II, the Traugott Golde offices and plant in Thuringia ended up in the Soviet occupation zone of Germany (in what would eventually become East Germany), so the Golde family relocated to Frankfurt and formed a new company dedicated to making sunroofs and sliding canvas roofs. The official name of the company is Hans Traugott Golde & Co. GmbH, but virtually everyone refers to it simply as Golde Schiebedächer (literally translated as “Golde sliding roofs”).

Golde did bring one key innovation to the sunroof space: While the Pytchley roof was literally just a steel panel that one had to slide by hand, Golde added a cable drive mechanism that could be operated by either a hand crank or an electric motor, either one of which required less arm strength than muscling a steel panel around.

Golde found a much more receptive audience with OEMs after the war than before. By the mid-1950s, Golde was supplying factory sunroofs to Porsche, Volkswagen, and BMW. Mercedes-Benz was notably not a customer, but some Golde sunroofs still found their way to period Mercedes cars via the aftermarket. Today, Porsche 356 and VW Type 1 models factory equipped with a Golde sunroof are highly prized and sought after.

For a second time, Golde set up shop in the United States to expand its reach. This time around their target audience included manufacturers, so Golde opened an office in Detroit. By 1960 Golde had landed two big OEM customers: First was Studebaker, to whom Golde sold their sliding fabric roof, which Studebaker would offer as a “Sky Top” option until 1963.

But more pertinent for this piece, Golde convinced Ford to offer a sliding panel sunroof option on the 1960 Thunderbird, making it the first post-war US car to be so equipped from the factory. Ford heavily promoted the sunroof, featuring it in TV commercials, print ads, and giving it prominent placement in the brochure. Ford set up a dedicated section of the plant for sunroof installation, which was a time-consuming and expensive process. The sunroof models also required numerous unique trim pieces, such as the headliner and a wind deflector mounted to the windshield header, which further increased costs.

Ford ended up selling only 2,536 sunroof-equipped Thunderbirds in 1960, about half of what they were expecting. Part of the blame can be attributed to the high cost of the option ($212.40 in 1960, about $2,000 in 2021). Making matters worse, most of the sunroof cars were further optioned up with expensive options like air conditioning, power windows, and upgraded engines, if the surviving examples I found on Google are any indication.

For all that money, the sunroof panel you received was not actuated with an electric motor or even a hand crank. Rather, one had to strongarm the panel open and closed, as shown in the video above. As previously mentioned, Golde already had the technology for crank- and electric-powered sunroofs, so I’m not sure why Ford opted not to use these. I’m guessing Ford went with the simple sliding panel for cost reasons. As a result of the poor sales, the sunroof would be a one-year-only option, with Ford dropping the option in 1961.

With only limited success selling to automakers, Golde closed their Detroit office in 1962 to focus on selling directly to consumers. Based on the ad above, Golde apparently had a view of Americans that was simultaneously highly stereotypical and yet strangely on the nose at the same time.

The never-ending treadmill of patent expiration is a constant threat to any manufacturing business, to which Golde responded by continuing to innovate. In 1973, Golde debuted the world’s first tilting and sliding sunroof, which started appearing in select Mercedes-Benz models shortly thereafter.

Also in 1973, Golde GmbH was acquired by Rockwell International as part of a large wave of acquisitions of European automotive suppliers in the 1970s. Rockwell spun off their automotive holdings in 1991 to form Meritor Automotive. After numerous additional mergers and divestitures, as of 2019 the European automotive conglomerate CIE Automotive now owns the sunroof business that can trace its lineage back to Traugott Golde.

Next up in part 2, I’ll take a look at the company that largely defined the modern sunroof, American Sunroof Corp (ASC).

I’ve only had two power moonroof/sunroofs. Both on black cars, baking in the sun for decades, and neither ever leaked.

Maybe I was lucky.

Neither one came with a hottie in a cowboy hat with a rifle, (not even as an option) so not as lucky as I could have been.

All modern tilt-and-slide sunroofs leak (since there is no way to seal a panel that can both pop up and slide under) The actual opening of a modern sunroof is considerably smaller than the size of the panel, so there are “gutters” all around to collect the leaked water. There is a drain down one of the A-pillars. When the drain is clogged, the water will back up and leak into the interior.

My son has a 1991 Citroen BX with a power tilt & slide sunroof that doesn’t leak and he uses it often. We both agree that he’s lucky. I wish my modern car had one.

I had 2 Nissans – a Maxima and an Altima – in which the drains clogged. The Altima was much worse than the Maxima. There were in fact four drains – in in each A and C pillar. To make matters worse, each had a one way valve (supposedly to keep dirt out from the bottom) which made them much harder to clean. Once the car was eight years old or so, it was a ritual every few months; one would invariably clog. One of the A-pillar clogs required the removal of the windshield wiper assembly to get at the valve, which was between the firewall and the windshield. I would never again buy a Nissan so equipped.

The Peugeot 402 B had a sliding sunroof from 1938. Similar to the GM on you have in the article, though it predates it by a year. After the war, all Peugeots were available (and often ordered) with a sunroof.

“Know the True Pleasure of Exiting Motoring”

What does that mean?

Do you “Exit” the automobile through this sliding roof? I think they meant “Exciting.” We don’t need no stinking proof-readers.

Interesting, because if there was a typo to be made, I’d have expected it in the body copy, not the headline!

They did mean “exciting”; it was correct later in the ad copy. I just found it interesting that there was a typo in the ad, in the heading, no less. Some proofer at the agency did not do his job!

Just noticed that BuzzDog beat me to the reply –

This thread has given me an idea to create an article of my own about another somewhat common automotive accessory….

I’m been fascinated by sunroofs ever since my family and I spent 6 months in Europe in 1977. My parents bought a circa 1972 Ford 26M sedan for the family to travel around. The purchase (and eventual disposal) of this car is a story in itself for another time….I remember the car well. lIt was silver, and an automatic (as I think all the 26Ms were) with a black vinyl roof and…. a factory electric sunroof.

I played with the sunroof endlessly (it operated without the ignition) almost draining the battery. From memory there was a smoked great plastic wind deflector stuck on the roof which may or may not have been factory.

Sunroofs (and I mean proper factory ones) and were not common around here, except for more expensive fare like Mercedes. I was a snob from way back and detested those fabric roofs that Webasto and the like offered, and not to mention those cheap look plastic bubble hatches and those glass sliding panels thr were stu k on the outside of the roof. I don’t like factory sunroofs in current cars as they are made of glass and look like an afterthought.

Whrn we were in Europe I noticed

that a sizable number of cheap cars had factory sun roofs. In particular it seemed like every Peugeot 404, 504 and 304 had a sunroof. A lot of the Volkswagens did too. Even if they were manually operated by crank, at least they were a factory fitment.

Interesting for a market that had a tendency to be sluggish in picking up on car features and technologies, Ford Australia from the very late 1960s offered optional factory sunroofs in the Falcon GTs, Fairmonts and Fairlanes. The OEM manufacturer was Golde. It was quite a few years before Holden offered something similar. I don’t know if Chrysler ever did. It seems that Ford stopped offering the sunroofs later on.by the late 1970s. Perhaps they were out of favour or there were problems with leaks.

VW made Beetles with steel sliders here in the mid-’60’s. They seem to be most uncommon.

I never knew that! Despite writing to VW in primary school (1967) and getting reams of publicity material for my classmates, there was no mention of a sunroof. But then Aussies weren’t into sunroofs back then, and folk who bought Beetles weren’t the sort to spring for expensive options.

My father’s 1964 Beetle had a crank open sunroof. As kids, we were very unimpressed and preferred his 1959 Beetle convertible. I had no idea until now how unusual the 1964 was. We thought nothing about it.

My ’67 was a Deluxe Sunroof Sedan with metal Golde crank sunroof. The gaskets were semi-effective, so there were rain channels and plastic drain hoses in the body. I found out the hoses were blocked with dirt when I got a shower, with the sunroof closed, after a car wash.

This is interesting, and I had no idea that these early postwar sunroofs all traced to a single company. I think the order may be backwards in the first US models – the Thunderbird was 1960 as you note, but the Studebaker Skytop did not appear until 1961. It at least lasted until 1963, but the option was ordered very rarely and they are exceedingly rare today.

I recall these being moderately popular on VWs in the 60s, especially when they moved to the steel versions. My next door neighbor’s mom had a bug with the crank steel sunroof.

You did not cover the next steel sunroof wave that got going around 1970 or so as convertibles were disappearing from certain lines. The Continental Mk III and the big C body Chryslers are two I can think of seeing in brochures but never in person. But perhaps Part II will go there.

Yes, and even more recently, my ’86 GTi had the steel sliding roof with hand crank,

though sadly my current ’00 has been homogenized to an electric glass roof.

I’m kind of reluctant sunroof owner, have actually looked for a car without one for my last two purchases, but ended up buying one on both. I prefer the steel roof, though the glass roof has become pretty much standard, VW also bowing to the change. I live in the sunbelt, and spend most of my time trying to hide from the sun, so I use mine to ventilate the car when parked, very rarely using it as a sunroof (like maybe 2x/year if I think about it, at night, when it finally turns cool in late fall or early spring).

Don’t like the idea of a glass roof, as I’ve been known to carrying stuff on my roof without a rack…..used to have one, but as raingutters have disappeared, roof rack mounts have gotten specialized and pretty pricey, and some can only be used on a specific make of car. Also, we get hailstorms usually at least once per spring, my (sadly deceased) youngest sister had 2 cars totalled from them, including smashed sunroof glass on both. Similarly, my Dad never wanted to put solar panels on the roof of his house, back when he was still with us, and he’s one of the original people working on the first ones at Hoffman Electronics in El Monte back in 1959…some of his work went up on the Explorer 6 satellite (he only worked there a couple years, never working on solar cells again, instead on other semiconductors the rest of his working life. Maybe they’re a bit more durable now, but if so, nobody should be having to replace their roof, which doesn’t seem to be the case.

Great article! I’m a big sunroof fan and won’t have a car without one so I don’t like the trend towards non-opening panoramic roofs. One of the neatest sunroofs of the 1930s was the Riley Kestrel. The rails for the sliding steel panel were integrated into the design of the car. Difficult to find a good pic but you can get an idea from this one. I can’t remember any Mercedes having a tilt/slide sunroof until the W124 in 1984/5 – before that I thought they all had sliding Webastos. We had a 1973 Ford Granada with a tilt/slide Golde sunroof and I think Capris had them from 1974. In the U.K. at least Ford was the first volume producer to make sunroofs standard equipment and others followed suit.

The one sunroof in my “fleet” broke, one of the plastic guides that lifted the glass panel to the tilt-up position and lowered it to the slide-open position cracked. It apparently was not up to the job of supporting that much weight and the prior owner of the car must have used it a lot. I got the parts to fix it (under $35) but then realized that for something I had used myself about a dozen times…maybe…it was not worth stripping the upper interior and dropping the headliner. What I use a little more than the opening sunroof is the sliding sunshade to let the sun in, but only on cool days. To each his own.

Interesting article, though. I had no idea that the first sunroofs we’re from Britain. I’d have more expected them in warmer climes.

Great post, Mr H, an unlikely topic to be interesting (but then, our Counsellor Cavanaugh did one on white cars, of all things, and it too was great!).

Sunroofs – sunrife? – must work in climes where the sun is not as harsh as it tends to be in Australia, even in weak sun in winter. Here, they’ve always struck me as pointless (though rather ridiculously, if you don’t order your upmarket Euro with one, good luck with resale). In the past, in cars without a/c, by the time it was warm enough to open the top, it was too hot to let the rays in with the extra airs. Noises, pongs and dirts also came in uninvited too, all avoided by that delicious little button marked “A/C”.

Every single person I’ve known whose car had a sunroof opened it exactly three times, and never again thereafter.

Very good last point. 2 of my previous cars, a Honda Civic and a Subaru Liberty had sunroofs that I did not use all that much, mainly because of the wind noise/buffeting and excessive sun exposure on very hot days. The sunroofs were standard equipment so I had no choice. All very ironic although I like the idea of sunroofs… .

I deliberately avoiding getting a sunroof when I bought my current car a Golf, as it is basically a very large piece of glass that adds weight and complexity, and and has been known to creak and leak, and and in at least one occasion, the the entire panel cracked and fell off behind the car as it was being driven.

Sunroofs are interesting in that they work best in weather that one would not think they were designed, i.e., colder rather than warmer. While they’re okay when it’s warm and cloudy (blocking the sun’s rays), the opposite is true when it’s colder, since the sun actually works to heat the interior with an open sunroof.

Used in this manner, they’re not so bad. But on a hot, sunny day? That sunroof stays closed, the windows up, and the A/C on.

Probably accurate for most, for me my Cougar has a sunroof and I can say with absolute confidence that I have pressed its button to open a lot more than the magical AC button in the summers, BUT the Chicago the area does have a propensity for grey skies. When it’s hot and sunny I tend to only close the car up and draw the shade closed and press what I refer to as the emergency AC button.

My Dad was more the typical, he with few exceptions bought lightly used cars when I was a kid and his Audi 100 and Lexus GS both had them by fortune of simply being what was on the dealer lot, so while I was all excited we’d have a sunroof on road trips, he kept them shut nearly all the time with the AC cranked to tundra, probably the reason I tend to embrace sunroofs and open air motoring.

Rudiger makes a very good point about winter usefulness too, I always kept the shade upon when I still subjected that poor car to the season, on real cold but sunny days I’d forget to even use the heater on the drive home

I had the sunroof open on my 404 more often than not. It’s a climate thing: we lived in Santa Monica on the coast. It was perfect and I’m a fresh air fanatic.

I even had it open on long trip on the freeway.

Admittedly it was open somewhat less on my 300E, but still quite often.

Sunroofs originated in GB and Germany for a good reason: these are cool northern climes (at least they used to be) and their inhabitants were rabid sun worshippers, especially so the Germans. Convertibles are still popular there and have the highest market share of any country.

In the 50s in Austria fabric sunroofs we’re extremely popular and among other things afforded great views. And in the case of my 6’5” godfather it allowed him to sit fully upright in his Lloyd when it was pushed back.

Conversely they rather suck in hot climes. That explains your experience.

You’ll be happy to know that my last visit to Niedersachsen during July still involved overcast skies, showers, cool temperatures and sweaters. My favorite free hedonist pleasure was sunbathing and skinny dipping sans sun screen. I could spend the entire day in the sun and never burn. My wife and I love the weather there.

As to fresh air, I am always reprimanded on trains for leaving windows open by Germans. It seems that many fear drafts. This required courtesies on my part as well as understanding. There is no reason to disagree with a German, or you’ll never hear the end of it.

I’d heard the name “Golde” somewhere, and knew about the ’59 Thunderbird, but the rest of this is all new to me. I have a Ford Escape with a sunroof now, and–in Great Lakes climate—open it more and more between March and October, though sometimes just that little bit as a vent rather than full-tilt. September 2021 will probably be the most-used month of the year.

Henry Ford Museum has an image of something fancy from the “1959 NY Auto Show”–is this wagon a Mercury?

And for the very curious, Golde apparently had a popular exhibit at some Brit auto show in 1972: https://www.gettyimages.com/photos/sunroof-golde?family=editorial&phrase=sunroof%20golde&sort=oldest

That windshield/A pillar looks more GM, and the angled side trim suggests a ’59 Buick.

Looking closer, I totally see the GM greenhouse thing. Whatever the car was, it had the bucket seats (presumably not an option then) and some fancy upholstery…thanks for helping with this one! UPDATE: It must be this ’59 Buick “Texan” wagon: https://gmphotostore.com/1959-buick-invicta-texan-show-car-poster/

Peter is correct — definitely a GM product, most likely a Buick. That A-pillar shape is unmistakable, Harley Earl’s greatest achievement in wraparound windshield design.

Not a fan of sunroofs. When I leased a new Lexus RX a couple of years ago, I specifically didn’t want a sunroof but almost every one on the lot had it. Had no choice, so when the salesman demonstrated the sunroof, it was actually the last time it was ever opened.

I don’t know why anyone would want a huge panel of hot glass over their head if there isn’t a solid panel shade. Even with mine closed, I can still feel a little heat on a sunny day.

A couple of years ago, there was an early 30’s Cadillac V-16 “Berlinetta” for sale with an opening roof panel over the rear seat. But that was a custom body, possibly an addition during restoration. Closed cars didn’t have full steel tops until the mid-30’s. The Chrysler Airflow might have been the first in the US.

Before 1935 all closed cars had an opening in the roof that just begged for a folding or sliding panel. US carmakers filled the opening with a non-folding juryrig made of chickenwire and oilcloth, even though they could have easily gasketed in a fixed metal panel or a folding cloth sunroof. The Euro divisions of US carmakers were using the same tooling, but often filled the hole with a folding sunroof.

After 1935 better presses made it possible to form a solid metal roof in one stamping, without too many wrinkles or stretches. By ’38 all carmakers had adopted the new tech.

Then in ’39, when the hole was no longer necessary, Chrysler and GM cut out a new and unnatural hole for those rare sunroofs which nobody wanted.

Just a decade or two after people had been sold on the idea of a closed car being better (which undoubtedly it was), and only a few years after the advent of the all-steel roof! Good luck with that!

When my dad bought his ’61 Mercedes 190Db in 1966, I saw at the dealer my first sunroof. It was on a fintail 220, I think. That car also had A/C and an automatic, but was out of my dad’s budget, I’m sure.

Nearly all of the 2007-2011 Camry Hybrids I’ve seen have had glass sunroofs, including ours. (I think a lot also had leather seats and a whole package of stuff including navigation and JBL premium sound system.) In the spring and fall I kind of like opening up the roof and dropping the rear windows a bit to stop the buffeting. Not so much in the noonday sun, though. In the nine years we’ve had the car, it hasn’t caused a bit of trouble.

Good article on steel sunroofs but almost nothing on fabric ones, which are rightfully sunroofs too. The fabric ones were madly popular in Germany and Austria, where the cool summers (back then) made them very appealing to sun and fresh air worshippers, such as the inhabitants of these countries inevitably were.

The very first KDF (VW) prototypes were shown in 1938 in three body styles: hard roofed sedan, fabric sunroof sedan, and convertible. The fabric sunroofs were very common on VWs until replaced by the steel ones in 1964.

All German manufacturers offered fabric sunroofs as the demand was so strong.

Aftermarket fabric sunroofs were quite popular too.

The fabric sunroof has one huge advantage over the steel one: the opening is twice ad big, affording an experience much closer to a convertible. I much preferred the fabric sunroof VWs for that reason over the steel ones, which were rather too small.

Folding fabric sunroofs, such as the one on this ’62 Dodge Lancer show car, which is widely assumed never to have been put on a production car, but…

…here’s a Swiss-built ’62 Lancer…

…with a folding-cloth sunroof…

…apparently made by one or another branch of that Golde outfit the US press release photo mentions…

…the handle folds, too (and I note the safety double-hinged rearview mirror bracket, apparently original, and six years before any such thing was put on the American-built cars)…

…to let the sun shine in!

I’m a big fan of moonroofs. I like the extra light in the cabin and find that the tinting on modern ones sufficient in our climate that I rarely close the shade. What I really like though is an opening panoramic roof and searched for sometime to find my current daily drive with one.

Much of the spring, summer and fall my hand normally hits the start button, then moves to the button to open the roof and then to the storage compartment for my sunglasses. I do make extensive use of the climate control when it is hot or cold. I typically set it to defrost and either Lo or Hi and the result is that the air from it mixes with the air coming through the roof and it feels like you are driving in 70 degree weather whether it is 40 or 90 degrees outside.

1927 ad lists Chrysler, Sunbeam, etc.—is it all possible that Pytchley is adding these to the cars and selling them themselves, rather than actually doing it for the manufacturer?

That is sure how it reads to me, They have roofs for those cars and they will install one in your car or possibly sell you one from stock. It does not read like it is something you could order factory installed.

When I was in elementary school we had daily French classes that were taught by teachers who travelled around to the schools. For a couple of years my French teacher drove a blue Volvo 544. I think it must have been around 1960 and 61. On day he ended up following our school bus, and when stopped for a traffic signal he stood up through the sunroof and waved to us. I am fairly sure that it was a solid panel and not fabric. That was the first time I was aware of sunroofs.

I am a huge fan of sunroofs to the extent that many cars make me feel almost claustrophobic now if there’s no sunroof. Nevertheless, as several here have noted, in actuality, I don’t fully open the sunroof as often as I might think I would. It’s a strange phenomenon…having it, wanting it, but not that often using it. The giant “panoramic sunroof” in my E91 is an amazing thing. At least for front seat occupants. I’ve been told that it makes a lot of wind and too much glare for back seat passengers (since the opening extends to the rear seat).

But I actually came here to talk about the Thunderbird ad and to voice the opinion that we need more car ads featuring dogs.

I particularly like the part at the end where he pulls up along side the convertible. They both open their roofs. The dogs look at each other, and then they just drive their separate and opposite ways.

A strong Go Dog Go vibe about that one.

Great article, Tom. I look forward to reading part 2!

I have never liked sunroofs-for me, its a complete, instant deal killer unless the car is FREE.

All my purchased-new cars (5) have had sunroofs. Life’s too short to not have one. I do wish they were stand-alone options though – mostly they’re bundled with upper trim levels.

Love today’s moonroofs! When I’m alone in the car, the sunshade is open any time of year, and the roof itself is in the tilted up position.

Driving in Colorado requires either a convertible or a sun roof. There is as much to see looking up as looking around. While I lived there, I had both and nothing beats getting a little waterfall shower from the melting snow cascading off the mountainside!

Just watch that sun! You must wear excellent sunscreen or you will fry and blister!

Aha! I see the model-with-the-rifle is from a GM publicity photo for that 1959 Buick Texan–you can do some stand-up hunting from within the car. Bad Translation from Alamy: Jan. 01, 1959 – Latest craze: Car with high seat for hunting: A high seat for hunting has the latest model of Texan of t Buick car works which was shown at the car exhibition in C which was opened on Jan. 17th, 1959. The roof of the car can b opened electrically, and from there it is possible for the hunter to shoot the game. The Pretty Texaner on our picture standing on a gun box in which 2 guns with magnifying glasse can be kept. The car has leather seats and is especially use for country-men.

I find that it is more convenient to open the sunroof than to lower a convertible top. I will often park my car with the sunroof open when I make a short stop at a store or coffee spot. I’ve had cars with glass moonroofs, after market pop up sunroofs on my ’78 280Z, T Tops, on another 300ZX, and a couple of convertibles.

I found that I liked using the T Tops the least, as the car has to be parked, the tops unlocked then removed, placed in the covers, and then secured in the luggage compartment. If I was going to leave the car for an extended period than I would have to repeat the process. This resulted in their infrequent use.

I can lower the top on my Mustang while I’m stopped at a stop light.

Aftermarket pop up sunroofs were really popular as dealer add ons, my ’77 Z did not escape unscathed. The quality was good, but they didn’t add to the appearance of the car.

My ’51 Jaguar Mark VII came with a sunshine top. Luckily, it was almost completely closed for the twenty five years that it sat neglected. I haven’t gotten around to starting work on this project.

Sliding Steel roofs were common on lot of prewar British cars. Dads 1st car was a £25 1930s Morris, with a sliding roof. He took Grandad out in it an it started to rain. Sliding roof wouldn’t slide so Grand dad came up with a quick fix. He stuck his open umbrella up in the hole!.

What I don’t get is “Non sliding roofs” .Just a fixed glass panel to roast the interior. I rented a Nissan Qausqhi . Oh look a electric sunroof button. Press button. The sun shade rolls back to revel a fixed smoke glass panel. Why?.

Interesting read, thank you.

Though I’m all about the traditional open car, to me the slide-open is a trend that slowly crept up unnoticed and I never gave it much thought. Now I know.

A few years ago I was raiding a ’71 Eldorado at a parts yard. It had a factory powered sliding roof. I don’t recall ever noticing another.

I was sizing up the roof up for an attack by Sawzall. It would only take a minute to “harvest” the rare option. Then I considered the likelihood of the cut-out roof ever being reutilized, and if any value the roof might bring to a recipient car would be worth the effort? Just didn’t compute as worthwhile, I passed.

Instead I went for the OE labeled switch panel, mostly hoping that the roof switch might be the same as convertible’s – it wasn’t.

A sunroof is a “Never, ever” thing for me. When I was looking at cars, I would see perfectly equipped car after car, and there would be the sunroof. Everyone I know who had one regretted getting it, and there was no way I would even consider one. A friend cracked from his previous anti-sunroof sentiment, and bought a 2012 SRT 392 Challenger with one, and it was the only thing that car ever had trouble with. In 2017, he sold it and bought a Scat Pack 392 in the same Yellow Jacket, without the sunroof. That car, like my ’18 Scat Pack, has been 100% trouble free.

It took me six months to find a 6-speed SRT with no sunroof. I finally did, a 2013 SRT8 Core. I looked at a couple really nice Challengers, but couldn’t get past the hole in the roof.

I’ve been indifferent to the roofs, take it or leave it, but by luck of the draw have ended up with a bunch of ’em in “drivers.”

Although I mostly had a “don’t open that son of…” policy just to not have one get stuck, or begin to leak. However, I don’t remember one that gave any trouble or leaked after its seemingly inevitable use.

I have always had sunroofs in my cars, mostly for the additional brightness it offers the cabin. I rarely opened it. Here is a pic. of my first new car with an aftermarket sunroof: my 1989 Plymouth Sundance “Highline” (trim model), with the pop-up/removable glass sunroof. It got installed by ASC (American Specialty Cars), right at the factory, while I waited! I loved that car! I also had sunroofs installed on my 1998 Suzuki Esteem GLX wagon, and 2003 Hyundai Accent GL 3-dr. hatchback. Here’s a photo of my ’89 Sundance.