“I want one of those cars that fixes itself!” So declared my mother—I guess after misunderstanding a news item about computerised engine control or something of the like. I was in the fifth grade; it was 1987, and my folks had decided their trusty but ageing ’78 Caprice and growing-raggedy ’77 Cutlass were due for replacement.

The story of the Cutlass’ replacement is too juicy to tell just yet. Alright, then; what came after the Caprice? It was going to be another 4-door sedan with automatic transmission, because that’s what my parents drove. But what make and model?

As I say, it was 1987—right around the peak of the executive-strength conspicuous consumption trend. Mother, once she understood there’s nothing such as a self-repairing car, wanted to see about these Mercedeses that were popular amongst the popular. The W126s, W124s, and “baby Benz” (oy vey -ed) W201s, whether new or used, were well above the target price range, so there was no trip to a Mercedes dealer. We went to Walter’s Star Service, an independent repair shop probably named that way to avoid a cease-and-desist letter from Mercedes. They had several 4-doors for sale on the forecourt. I recall thinking it strange to be sniffing around ’73-’74 models to replace a ’78, so that probably means they were W114s and W115s, though there might’ve been a late-production W108 as well.

To Americans like my folks, accustomed to Torqueflites and Turbo-Hydramatics, the German ideal of an automatic transmission’s shift quality was like a German joke: far too hard to understand. Back at the forecourt, mother asked about another car and, on learning it was a diesel, said “I don’t know how to drive a car that takes diesel gas”. The remnants of her enthusiasm was dampened by Walter’s answer: “It’s pretty much the same, except if there’s going to be cold weather just make sure to add a gallon of regular gas when you fill up the tank, because diesel fuel can gel up when it gets cold, and then the car won’t start”. So that car was out before we even got in.

No Merc for us, then. Just as well, I guess; I can’t imagine whom other than herself my mother reckoned on impressing. And an unturbocharged diesel in a hefty vault on wheels at Denver’s altitude meant 0 to 60 probably sometime late next week. This I learnt for myself some four years later; my friend Ben’s W115 diesel (vanity plate BNSBENZ or maybe BENSBNZ) was the first car I ever drove—illegally, with no licence—on a public road for about ¾ of a mile. I was reluctant, but Ben assured me the car was so slow I couldn’t possibly get in trouble. He was wrong about that; there are plenty of ways I could’ve caused a major crash with a slow car, but none of them actually happened that day.

The Daimler dream dashed, my folks decided to stick closer to what they already knew. We went to a Buick dealer—probably Deane Buick again, now I think on it—and looked at Electras. Sister and I enthusiastically thought the Park Avenue looked excellent; mother scoffed and made tart remarks about paying for a name. You’re a doodle, mama! It was after dark; if there was any car actually test driven, I don’t recall it.

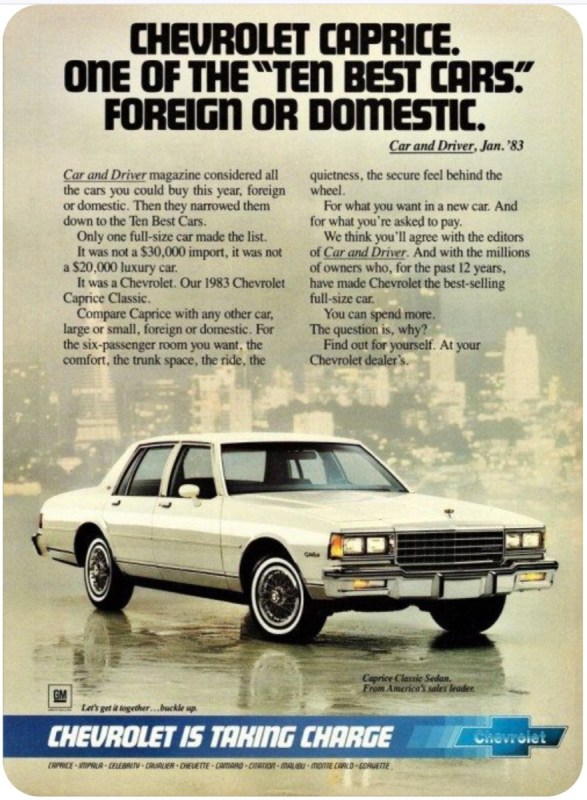

Consumer Reports had given good grades to the Caprice in a full road test in ’83, though they did find flaws (“You must rotate a medallion to insert the trunk key, a nuisance”). So one fine Saturday morning dad and I got in the red ’78 and headed for Spedding Chevrolet, a large dealership located near the junction of I-25 and US 36. This dealership, like Flannery Chevrolet closer to home, was in some kind of nasty but predictable legal trouble dad probably didn’t know about—false and misleading advertising, lying to customers; the usual and customary. They ought to have been hauled up on charges for this irretrievably stupid commercial:

Everyone behind the front glass of the showroom had a clear view of every car on the long downhill access road to Spedding, so a salesman with a great big smile was standing outside waiting for us by the time dad had stepped on the parking brake. He’d spotted a newspaper ad for a 1984 Caprice Classic, and soon we were standing before it: a white one with a pointless white vinyl top, a velour interior, and a 305 engine. We got in for a test drive—dad in the driving seat, salesman riding shotgun, and me in the back.

Most everything was familiar, but the prindle confused dad at first. Instead of Park R N D (…), this one said

P R N 🄳 D (…), and had an AUTOMATIC OVERDRIVE callout. He’d put the car in D, in accord with his habit of many years. Once we got on the open road, the salesman noticed and told him to shift to 🄳. Dad stepped on the brake and put his hand on the shift stick; the salesman, in a Slavic accent of some kind, said “Dunn’t brrek, jost shyift!” and explained (sorta) what overdrive meant.

I’ve written before about the Toastcat Effect; that time about a car—a Caprice, even—but this time about my dad: a very good attorney and easily the most scrupulously honest person I’ve ever met, and I fully expect that record to stand forever. Back at the dealership, dad said he liked the car okeh, but his wife had said no white cars. Great lawyer; lousy liar, so it never occurred to me that he would utter a word of anything short of truth. I helpfully piped up and reminded him: “No, dad, mom said she wants a white car!”, interrupting his question about whether the car could be painted and spoiling his attempted negotiation tactic.

Oops. Dad was cool about it; he didn’t get angry or anything. He later explained—a little sheepishly—what he’d been trying to do. I don’t remember why or by what process of negotiation, but onehow or another he wound up buying that white ’84 Caprice. I don’t recall any others being tested or examined. This is kind of weird, as I think back on it. He wasn’t in an urgent rush, and Caprices weren’t exactly scarce; what was so special about this particular one? I’ll never know.

Right from the start there were issues. No big, egregious failures or dramatic blow-ups, just…issues. Foremost, the transmission shifted hard—Bang!—just like the Mercedeses they’d not bought for that reason, ahem. There were trips back to Spedding for their service department to have another try at fixing it. Eventually they got it to behave less convulsively. I don’t know whether it was a TH200-4R or a TH700-R4 transmission in it, but it was never as well-shifted as the TH350 in the ’78. And it didn’t sing in first gear.

I wasn’t in mourning like when the Dart went away, but I had a list of gripes with the new car. Okeh, there was the FM-AM stereo radio and the power locks and the tilt steering column and the chrome dressup trim in the doorhandle carve-outs, but the ’84 felt chintzier and cheaper of construction at just about every turn. Kicking the floorboard sounded flimsier, less substantial. Closing the door sounded tinnier, less thunky. The high- and low-note horns didn’t harmonise with each other. Same glovebox door as the ’78, but that car had a check cable to stop it at a fully-open position; the ’84’s door just fell unhappily against the hinge. The large oblong panel above the glovebox (where would’ve lived an airbag had GM gone ahead with that plan) was high-quality, mirror-glossy, sturdy black plastic on the ’78. On the ’84 it was thin, bendy, and with an oily-looking matte finish; they’d squozen it for every possible centicent. The ’78 had round gauge-centre covers so only the red pointer tip was visible; these were deleted on the ’84. Same fuel filler location, behind the rear licence plate which was mounted to a spring-loaded, bottom-hinged access panel. On the ’78, the panel had a little finger hook to grab and easily lower the panel to get at the fuel cap. No finger loop of any kind on the ’84, we just had to dig at the side of the licence plate to get a grip on it. The notorious plastic tapes never broke in the ’84’s window lifts, but I hated them; they required what felt like sixty turns from closed to open, and they cranked the opposite direction from the real window regulators in the ’78. The front windows themselves were noisy; they made a ghostly wailing noise on the way up or down, no matter what remedy was tried.

The interior of the ’78 had been scarlet red, which was fine. The ’84 had what was probably marketed as a “wine” or “maroon”, but in person was unsettlingly closer to a raw-meat colour palette (by which I mean the various parts didn’t exactly match). I don’t say the raw-meat look caused carsickness, but I do recall a few times it certainly didn’t help alleviate it. I thought Mrs. McClintock’s Caprice was better—also white but with a nice blue interior. And hers, being an ’83, had a matching blue shift knob, shaped in accord with Scripture where it says what the gearstick knob’s meant to look like in a Chevrolet. The ’84 my folks had bought, like all other GM ’84s, instead had an awful chrome-and-black thing of the wrong shape. I wonder if “new corporate-wide shift lever knob” made it into the 1984 version of this trainer:

Also, there were phony-wire-wheelcovers. I thought them tacky and overdone compared to the more tasteful stamped ’78 wheelcovers. Just as on the ’78, there was one sideview mirror, a chrome remote-control item on the left, but on the ’84 it had a disagreeable random shape sort of like the palm of a hand minus thumb and fingers. GM used this hand-shaped mirror well back into the ’70s, but the ’78 Caprice had a rounded rectangle that coordinated better with the overall design of the car. The rectangular mirror also probably provided a better field of view than the palm-shaped ’84 item, but at least the car didn’t have those uselessly miniature body-colour “sport” mirrors. What sport would that be, exactly? There was no right-side wing mirror.

But worst of all, it didn’t sing in first gear. That acceleration windup and deceleration spindown the ’78 had, and the ’77, and the ’70…gone from the ’84. I missed it every…single…time I was in that car.

It had a Quadrajet 4-barrel carburetor, controlled by a one-wire oxygen sensor and a mixture control solenoid that went “TICKaTICKaTICKaTICKaTICKa” when the ignition was switched on before the car was started. It had a higher-speed starter motor that sounded unpleasantly hyperactive compared the ’78’s mellower crankover. They’d deleted the cold air intake duct, reverting to the less expensive late-’60s/early-’70s type of air cleaner snorkel. This and what I guess to be lighter body insulation and less of it meant the engine was quite a bit louder in the ’84. It had a quartz clock with one “tock” per second instead of whatever sort of clock the previous non-quartz one had been, with a “tick” or a “tock” every half-second.

Halogen sealed beam headlamps were optional at extra cost on the ’84 Caprice, and this car didn’t have them. It did have a turn signal stalk overloaded, as GM did, with clunkily arranged multiple functions; let’s see here: turn signals, high/low beam, cruise control, windshield wiper, windshield washer. The windshield-integrated dipole antenna didn’t work very well; I’m pretty sure those just never did. The air conditioning compressor was a noisier, more leak-prone R4 rather than the quieter, more durable A6 in the ’78, but—like the tape-drive windows and the chintzier construction—this was a weight savings.

So yeah, I gripe, but the car did fine for the most part. It just had a much thinner margin beyond “good enough” in its materials and construction, compared to the ’78. It ran better, surely, in part due to its monolithic catalytic converter. 15ish miles to the gallon around town, but 25ish on the highway thanks to the overdrive 4th gear.

When I was about 14 or so, I noticed the car’s stop lights didn’t come on when dad arrived home from work. I told him it was probably the switch, for all four of them to have gone at once. He took the car to Clay’s Texaco, who did indeed find and replace a dead stop light switch. Dad thought it was cool that I’d reckoned it out on my own.

By and by, the muffler started making noise. By that time I was in high school, and taking auto shop. The shop had three or four double-width overhead doors, at least two hydraulic four-point vehicle lifts, an alignment-style drive-on hoist (don’t recall if it was actually an alignment table), compressed air throughout, a brake lathe, a sandblaster, a big multi-oscilliscope engine analyzer, an outside vehicle “impound” yard, and a tool room very well equipped with high-quality hand and power tools, testing and diagnostic equipment, and parts and service manuals. All built and equipped in the early or mid ’70s when metal shop and auto shop were still very much a thing. Trawling through old yearbooks revealed that the shop teacher, Mr. Schultz, was also installed about that same time.

Not everyone at school was a grotesquely overprivileged 1% type given a new Audi or Bimmer for their 16th birthday by money and daddy…but those kids made up a large chunk of the student body, and the auto and metal shops were about the only respite from them. In shop classes we got the greasers, the stoners, the ones flunking everything except Smoking Area, the kids from the wrong side of the tracks, the hard-luck cases, and…

…me, an underaged, paunchy, cloistered, closeted, hopelessly nerdy goody-two-shoes, dweeby little knowitall dork with glasses, a giant vocabulary, and a quick mouth. Fortunately I knew enough about cars to garner just enough respect to ward off what would otherwise have been a cooperative, it-takes-a-village campaign to stomp the everlovin’ crap outta me on a regular basis.

The vehicular population in the auto shop was a mix of cars donated by students’ families—a ’72 or ’73 Torino, a ’79 Malibu, and a ’77 LeSabre, amongst others; those donated by automakers—a new-never-sold ’86 Dodge B-van that had fallen off the train en route to the dealer, for instance; the motley, mottled crew of students’ own jalopies (’68 or ’69 Cougar, ’65 Chev, ’57 D-100…); and a rotating assortment of students’ parents’ cars brought in for cheap and educational repair work that otherwise would’ve been handled by a repair shop. No guarantees. Oh, and Mr. Schultz brought in a variety of his own cars: an ’84ish VW Quantum wagon, an ’82ish Olds Cutlass coupe with the miniature V8, a ‘seventysomething GMC or Chev 4-door long-bed pickup.

There wasn’t a whole lot of formal instruction; matter of fact, thinking back I don’t recall any instances wherein we sat in the classroom, learned about a particular procedure or automotive system, then went out to the shop to practice whatever it was. There was an exam or two, probably to meet minimum requirements for calling it a class, but overall I guess the feeling was that only dead-enders and losers with no real potential took auto shop, so why bother wasting any effort beyond stopping them killing anybody or burning down the school. Mostly it was just semi-supervised horsing around with cars.

And there was a fair amount of horsing around. In the metal shop we’d put a coin in the spot welder, switch it on til the coin was incandescent, then release it into a waiting bowl of water—just to hear the PYOOSH. Similarly pointless monkeyshines in the auto shop: put an exhaust hose on the Malibu, start it, and see how close the other end of the hose could be brought to the air cleaner snorkel before the engine would die. Watch what happens if the windshield washer tank of the Torino is filled with transmission fluid and the washer hose line connected to a vacuum port, then the engine started and the screenwasher button pushed. Stupid stuff like that. Mr. Schultz would holler at us if it got too far out of hand, but mostly he was pretty easygoing. He had a cash account with the local NAPA, where the counterstaff were friendly enough to let us kids have the same discount if we mentioned we were in Schultz’s class.

My folks and I went to that NAPA and picked up an intermediate pipe, muffler, and tailpipe, and some days later my sister—three years older than I, and in possession of a driving licence—drove us to school in the Caprice and parked at the auto shop. In class we started the R&R, but a class period was 50 minutes, and it needed more time. No worries; the afternoon class finished up the install.

I had classes all afternoon, and I didn’t make it back to the auto shop until after last period. It was closed and locked, and the car wasn’t outside it. Sister nowhere to be found, nor Mr. Schultz or anyone else. Drat! I peered through a window in one of the roll-ups. There in the middle bay was the Caprice, shiny new tailpipe hanging in perfect position.

Sister was going to be awhile with one or another activity, and faculty-staff density was dropping rapidly. I chased down and pled my case to the woodshop teacher’s wife; she worked as a secretary at the school, and she obligingly unlocked the shop door and let me in. I opened the roll-up and…then…um…what now? She was standing there, clearly waiting for me. The key was in the ignition. I might’ve been only 14, and I might not have had a licence or even a learner’s permit, but I knew the principles involved. Really, how hard could it be to back the car out of a double-width bay, straight out into the parking space directly across from the door? Remembering my imperfect first attempt , I thought about what I was doing.

Because I remembered to kick the accelerator, the engine started right up. Eh, presto! Got it right this time! And hey, no more muffler noise! Feeling confident, I carefully looked over my shoulder and pulled the column shifter into Reverse.

But also because I remembered to kick the accelerator, the choke had closed and the carburetor had gone to fast idle. It had a very fast, fast idle.

So because I didn’t kick the accelerator again to drop the idle cam off its highest step, and failed to put my foot on the brake, there was a screech from the tires and the car lurched backwards. WHOAHHH! I stood on the brake, dragging another screech from the tires on the epoxied shop floor. I put the transmission back in Park, shut off the ignition, and shook myself out the car and over to Mrs. Woodshop. Could…um…could you…back it out for me…please? Um…I…don’t have a licence, um…please don’t tell my parents I tried to drive it?

I never heard a word about it, so I imagine she figured no harm/no foul.

There were other times we worked on that car at the school auto shop. Once I almost got myself beaten to a pulp about it: the car was in for something or other—maybe plugs, wires, cap, and rotor—and I came back to it at the end of the day to find the Caprice parked outside (good), but with green coolant leaking, drip-drip-drip, from the radiator petcock (bad). Somehow or other I got it in my head that one of the wrong-side-of-the-tracks kids had opened it, the one who smoked GPCs and had the mangy ’65 Chev. Maybe I thought he had it in for me because I had mouthed off to him at some point? Fairly solid bet, but I don’t recall. I accused him directly and denounced him to the teacher, without shred one of evidence. He angrily denied it and things almost came to a fistfight, which I would have lost quickly and spectacularly. I had to lie low and make myself scarce around the shop for awhile. Three cheers for lessons that don’t escalate to the nose-remodelling stage.

I think I might’ve contributed to the end of the Caprice; I might’ve decided it would be a good idea to clean out the engine with some crankcase flush. Whether or not, the engine began blowing enormous amounts of oil out the tailpipe. I had the (cockamamie) idea to take apart the engine, and dad went along with it. We might have got one bolt out of one valve cover before realising even if it hadn’t been in the dead-cold middle of dark Winter in a not-very-well-lit garage, this was an unfeasible project for us. The car wound up in the impound yard outside the high school auto shop. No rust on it, no dents, nice interior (condition, still not colours). I think it eventually went off for scrap.

We’re getting into a car-dense time of my life, where there’ll be multiple cars on parallel timelines. Things are going to jump around a bit. Next week I’ll tell what came after the Cutlass.

Should have gotten the ’87 Park Avenue. My dad bought one in gold with gold velour. I convinced him to get the T Type package so it wouldn’t bounce around as much or look under-tired. Unfortunately, the GY Eagle GTs cupped early and loudly, and it took him years to replace them because they still had tread. The passenger upholstery seam split at my first sitting in the dealer’s lot, but he had few other problems until the headliner let go in the late 90’s.

I think you’re probably right that a carefully-chosen and thoughtfully-specified FWD GM car with the 3.8 V6 would’ve likely been a much better choice. A Cressida, probably even better.

We have some parallels in our stories. My parents were car shopping around late 1985 or early 1986. The ’79 Ford Fairmont dad was replacing was a nightmare and wasn’t far off the junk yard (it ended up there in 1987). I recall dad looking at those “new fangled” Magic Wagons at the Dodge dealer but dad was unconvinced. He figured sticking with old tech likely be more reliable. I recall going on a road test of a new Country Squire, but Dad didn’t want to spend that much. So when the Ford dealer got a trade in of a super low mile like-new ’84 Parisienne wagon (essentially a badge engineered Caprice), he jumped on it. Our car was a stripper, with almost no options. So there were some aftermarket parts added on, including cruise control (with the multi-stalk controls) and an Audiovox tape deck with dual rear speakers, but a real mast antenna. Dad also added carpet to the cargo area, since it had none. Although the Pontiacs did come with dual mirrors as standard equipment.

Our car proved to be very reliable, more reliable than our late 70s B-bodies, but I too noticed the difference in lightness compared to the ’77-79 models. The doors on the newer cars were much lighter and less solid feeling. Like you said, the window winders were backwards but ours never gave any trouble. Being a Canadian car, it had a fully mechanical Q-jet that served nearly 200K miles without an overhaul. It had a TH700-R4, that despite it being an early model, lived a long life with zero maintenance. With the 305 and the OD transmission, it was very good on fuel for the times. I also remember the brake light switch failed on our car too. Dad diagnosed and replaced it.

Like you, I also did some of my earliest repairs on our ’84, After my parents split up, I took over the vehicle maintenance on the Parisienne for my mom. We didn’t have auto shop in our high school, so I did the repairs in our driveway. I recall my friend and I changing the fuel pump, because it “looked old.” I also did the muffler repair too, but found out it was easier to do the whole exhaust from the cat back in rust country.

Thanks for another great read Daniel!

This ’84 I wrote about was built in Canada—Oshawa, I guess—but to U.S. specs. Canadian emissions regs were sort of stalled at roughly the U.S. 1977-’78 levels of stringency until they were brought into alignment with the U.S. regs for 1988. I suspect dad’s ’84 had a 700R4 transmission, but as I say, I don’t know for sure.

Small wonder those brake light switches failed—about a hundred and ten watts’ worth of bulbs pulled power through it, plus whatever additional draw from long lengths of what I am sure was marginally-specified wiring, and there’s no doubt GM twisted the switch supplier’s nipple about cost.

Being an huge fan(since childhood)of the Pontiac brand, when I saw the similar year Parisienne sedan, I was flabbergasted. I said, to Dad, “either I need new glasses or, GM put the same back end(rear door openings, back)on the Pontiac, as it did on the Chevrolet! Not impressed, at all.

Same front, too. The differences were superficial: single large tail lights instead of triple small ones, slightly different grille, different nameplates, different steering wheel and interior door pulls.

Drove lots of Box B-bodies from the late 70s until the mid 80s but never a sedan from that final year of box production that would have finally had TBI on the 305.

Still harbor hate for the eQudrajet.

My favorite though was likely the bronze/brown (with vinyl interior) base Impala wagon that my dad was assigned by his employer for a short period of time. I don’t recall if it even had AC or a third seat (I think it was a 78 or 79 model) but there was something so straight forward and humble about it.

Can I be the only CC reader who has owned only US-make cars but has never driven one of these GM B-bodies? No rentals (though I once turned down a bathtub Caprice for being ugly, for which Hertz substituted a Buick Park Avenue) and no police cars (ours were all Chrysler and Ford except for the 1977 “Smokey and the Bandit” Pontiac LeMans). At this date it would be hard to drive one and understand what they represented in the late 70s.

I did rent a RWD Cadillac deVille once…a C-body removed quite a ways from a base Caprice or a Catalina. This was well into the FWD era so the GM RWD was already considered an old design. It was phased out the next year or so when the GM Arlington plant was converted to light trucks.

I don’t have experience with the Chevy of that 1980+ era, all of mine came in the 1977-79 cars. I never liked the newer version as much, for both the styling and the clear cheapening of everything. I did have some experience with the related Buick, Olds, Cadillac cars of that generation, though.

I remember being really surprised when in 1985 Consumer Reports was giving higher marks to the Crown Victoria than to the GM B body cars. When my mother started making noises about a new car to replace her 80 Horizon I was sure that a final year Olds 88 would be in her garage. But no, she followed CU into the Ford Dealer.

That was really a dismal era for larger cars. There was so little to like about them, even though they employed their manufacturers’ most durable platforms/components.

It is usually easy for me to cast wholly-deserved aspersions on Consumer Reports, their methods, their attitude, and their blind spots. Sometimes—such as right now—it’s even easier. Notwithstanding the perpetual zero-sum Ford v. Chev coal fire, there are very sturdy reasons to prefer a Caprice (or rebadge) to a Panther car. Even once the Ford had a much better induction and engine management system starting in ’86.

A good read, thank you! We had numerous ’77 and up B bodies in our household, usually of the Caprice and Delta 88 variety.

Much agreed that the ’80 refresh cheapened these cars. The sheet metal was thinner gauge to drop weight, making the cars very ding prone.

Also agreed that the Caprice interior went from serviceable to chintzy. Interestingly, the Delta 88 seemed to continue to use the ’77-’79 Olds interior with little change and was generally a lot more pleasant to be in – probably the reason we switched from Chevy to Olds in those years.

The Olds did suffer the crappy window regulator changes, even in the power window cars. The window would drop into the door like a rock, leaving you with a problem if the weather was poor.

I fixed one of those power regulators myself, a PITA project. The entire damn mechanism was riveted to the inner door structure, requiring a drill out and a trip to True Value for the hardware that didn’t come with the regulator I bought at the dealer.

Many years later I replaced a regulator in my 2002 Dodge Durango. It was properly screwed and bolted to the inner door, and even the aftermarket regulator was plug and play with the original Mopar hardware.

What GM was thinking in the ’80s with the foreign and domestic competition refining their quality game while GM was simultaneously cheapening theirs, I’ll never understand.

At least the interior was still happy place in the Olds…..

That interior does look quite a bit nicer than the Caprice’s, though it has that same abominable corporate shift stick knob in place of the proper Oldsmobile item. I wonder (no, I don’t; not much) whether the Caprice interior was cheapened to push some buyers into more profitable Oldsmobiles.

As to what GM were thinking: this week’s profits, beyond which nothing mattered or existed.

The high school where my sons attended had an auto shop classroom, but all I heard about the students in those classes ever working on was lawn mower engines.

Most enjoyable (and educational) times were in auto shop. Had a great teacher.

I’d like that episode of LITB better had they not dubbed in starter and engine sounds (and interior shots) completely wrong for the ’62 Plymouth.

Oh Daniel, this one really hit home for me.

Our 1981 Impala was so much like your 84 in some ways, a solid design that had been cheapened out. Being a lower spec impala we had the stamped wheel covers and a simpler dash. Still chintzy, but at least not chintzy and ornate. You were lucky to have the 305 and not the 267.

That shot of the tailpipe made me laugh out loud, I’d forgotten I did the exhaust on it once and snaking that crazy tailpipe over the axle without a lift was very difficult.

My high school experience sounds like yours. There’s a line in Stephen King’s “Christine” that really jumped out at me when I read it as a teen, something like “Arnie’s interests unfortunately brought him into contact with people he should not have been in contact with”. As a tall gangly weakling with braces in my smart mouth, I came very close to getting right pounded a few times but it never went quite that far.

Thanks for this enjoyable read, looking forward to the next chapter.

Thanks, Doug.

I probably might’ve cribbed “…flunking everything except Smoking Area” from Christine, for the matter of that!

A great piece, Daniel – thanks! And for including my favorite line from Driving Miss Daisy…

A lot of teen-aged misfits – and I certainly fit into that category in the 1960’s rural Midwest – gained a degree of respect and stayed out of some trouble by knowing a lot about cars even if we were the farthest thing from being actual gearheads.

Never had high school shop class (but in Jr. High last year had progressive arts program where boys had to take home economics (rebelled greatly then, but now appreciate exposure to cooking and rudimentary sewing) while the girls had to take a stint in shop (rebuilt a 5 hp motor). Once I got to high school (50 years ago) didn’t get to take shop or auto repair, but (despite mostly being in academic program with “regular” math/science classes) I took 2 electronic classes…this was well before computers were common, so they were really “analog” based, 1st one was what you’d likely expect, circuit theory, etc. but the 2nd one was television repair (that was big 50 years ago). The instructor would put bugs on the sets and we had to diagnose what was wrong (not so much fix) and we learned to do alignments and so on…Motorola “works in a drawer” sets guess donated by some local merchant. Kind of think back on it but it was pretty dangerous environment, you can get hurt pretty bad if you’re not careful (but of course that’s also true of auto shop, and I guess pretty much any shop class

Wish I had taken other shop classes, mostly found out how little I knew when I started working at my profession with mostly older co-workers some of whom had full shops at their homes. One time went to one of them with a 3rd co-worker who was building a recumbant bicycle out of the tubing from my recently crashed bicycle. Even my working on cars was pretty much self-initiated, even though I had an Uncle who was pretty good with them, he didn’t live very close, and my father wasn’t really interested in them, though we did have a father/son project building a Radio Shack electronic ignition for his ’73 Ranch Wagon, but it ended badly when the coil on the wagon went bad after which my father blamed the kit and tore it out of the engine compartment. Maybe now as retired will try community college class to fill in the gaps. Seems like there was always too much to learn that didn’t fit in the 4 year (or 6 year or ? postgraduate training) profile, so you took the “main” classes but there was bound to be some area that got missed.

After the Ranch Wagon (my father never kept cars long) he bought a ’78 Caprice Classic Wagon with the 305. Probably the plushest car he was to ever own, bought it from the showroom, it was sharp, maroon interior (vinyl)/exterior (but with mandatory woodgrain). Even the Ranch Wagon had air conditioning (our first) and power locks (but not windows) and AM/FM stereo, along with trailer towing package it actually had more stuff than the previous Country Squire it replaced, but the Caprice Classic was plusher still. Recall he did look at the new Panther it had just come out, but decided to get a leftover ’78 (fall of ’78). The Caprice was plush, but didn’t seem too durable, it had sniggling problems like light switch that broke, and other minor stuff that compared to the Ranch Wagon we never had problems with. Unfortunately the Caprice met it’s demise in 1984, my father was hit by a car in Johnson City, Tx, when he was taking a relative on a tourist trip to the Johnson ranch (we didn’t get many relatives visiting, having moved 1600 miles away from where both my parents are from)…coincidentally the relative was driving a ’77 Impala (Sedan, pretty much base). Father really downsized, bought the worst car he ever owned, a 1984 Pontiac Sunbird, having had two completely new engines installed in it in less than 80K miles despite being dealer maintained per he service book. Father bought his last MOPAR, an ’86 Dodge 600, which itself seemed a decent car until my sister borrowed it in 1989 and had a terrible accident when t was totalled.