(first posted 4/27/2012) Grab the Kleenex; the Graham story is a real tearjerker. All too often, the good guys do lose; and timing is everything. The three Indiana-bred Graham brothers were already stars in the industry when they bought ailing Paige Motors in 1927. They instantly turned it around, and were a roaring success by 1929. You already know where this is going: all downhill, thanks to that little inconvenience called the Great Depression. But the Grahams never gave up trying, until it was all over in 1941. Sometimes they tried a bit too hard: the 1938-1940 “sharknose” Grahams only hastened the inevitable demise of the company. Never underestimate American’s conservatism, as Chrysler had already learned with the Airflow. Lean a grille a bit too far back or forwards, and folks think it’s a subversive plot. Oh well; at least Graham went out with style, if not in style.

The 1929 Graham-Paige was a handsome but not exactly a style-setting car, very much in the idiom of its time. But it was successful, with some 80k sold, a superb showing for a smaller brand. The Graham Bothers crystal ball said things were only looking up, and so they invested in a big new factory in Dearborn, Michigan. But it would never again produce that many cars, or even anything close to it.

Stylistically, the Grahams really made their mark in 1932, with the Model 57 Blue Streak. Unless one is familiar with the design subtleties cars of this vintage, it may not be apparent just how advanced this car was, without being too radical. Sryled by Amos Northup, who had created the superb 1931 Reo Royale, the Blue Streak took that very clean design one step further, with the first fully skirted fenders on a mass-produced American car. That, and the gracefully handled “radiator” grille, was a sensation, and the next year, almost everyone had skirted fenders too. Graham (unsuccessfully) tried to capitalize on that, proclaiming it as the “most imitated car on the road”. But sales were collapsing; down to an abysmal 11,000 for 1933.

For 1934, Graham tried another stab at innovation: the first moderately-priced supercharged car. The Custom Eight was available for as little as $1295, and the 265 inch straight eight delivered a healthy 135 hp, good for an honest ninety. In 1933, Graham dispatched the legendary driver Cannonball Baker with a pre-production Graham Custom Eight on a coast-to-coast run. Baker completed it in 53 hours and 30 minutes, which given the roads of the times was mind-boggling. It was this record that inspired Brock Yates to create the Cannonball Baker Sea to Shining Sea Memorial Trophy Dash which ultimately broke the still-standing record, some forty years later.

For 1936, Graham continued its down-scale death-march, dropping all eights, and concentrating on their 217.8 inch six, in both regular and supercharged form. In another cost-saving measure, 1936 and 1937 bodies were shared with Reo.

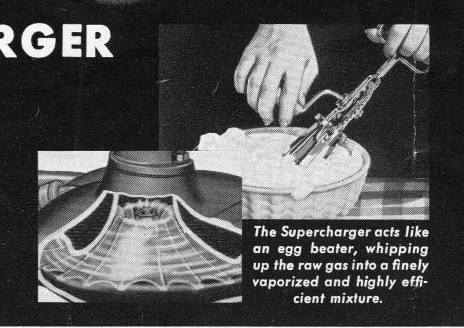

The Graham supercharger was essentially a down-scaled and simplified version of the centrifugal supercharger that Duesenberg used. Engine-driven and geared to run at up to 23,000 rpm, the little blower was designed more to fatten mid-range torque than a huge increase in top-end output. The sprint from zero to fifty took some thirteen seconds, excellent numbers for the times. Graham also was unique in using a four-speed transmission.

With the 217.8 inch supercharged six making 120 hp, the emphasis was more on its ability to make power comparable to a larger and heavier engine, and the resulting economy.

That approach is quite similar to today’s “low boost” turbo engines, but Graham was taking things a bit far…

with this claim. Maybe that’s where all those rip-off aftermarket “atomizers” mileage-boosters got their inspiration from. Sounds good, but…

In an act of desperation, Graham unleashed the radically-styled “Spirit of Motion” for 1938. Also designed by Northup, the forward thrust nose was very unusual for the times. Needless to say, the rest of the front end was anything but ordinary either. Typically, the press and design profession loved it, and it won numerous awards including the prestigious Concours D’Elegance in Paris. But a combination of bad timing and public wariness tanked the new Grahams.

In 1937 – 1938, the economy took another precipitous decline. The new Graham, as exciting and adventurous as it was, bombed out. First year sales were an abysmal 5020. Undoubtedly, Graham’s downward momentum was becoming a negative feedback loop. If this had been a Pontiac, it might have been a different story.

The 120″ wheelbase 3250 lb Graham could tick off the run to fifty in under eleven seconds, and top out at almost 95, and deliver up to 25 miles per gallon. But nobody was having it. We’ll stick to our tried and true…

What do a couple of good guys from Indiana have to do to catch a break? One innovation after another; they even pioneered the use of anti-sway bars. All for naught.

The Grahams weren’t called “sharknose” at first. In 1942, the Raymond Loewy styled PRR T-1 appeared, a massively complex, and ultimately failed steam locomotive. It was quickly dubbed “the sharknose”, and then the name was transposed unto the Graham. The really big question is whether Loewy cribbed the design from the Graham; actually, it’s not really a question.

Can’t say goodbye without a glance at the rear compartment. Cars of this era were so comfy back there, if a bit narrow. A tall sofa, and vast legroom; this and all the other Graham goodness for about $1200. I know what I’d be buying in 1940.

This very streamlined moderne taillight alone is worth that. Can we just take a minute and really take that in?

By this time, it was down to one Graham; Joseph. And in the final act of desperation, he threw a half-million of his personal money into an ill-conceived idea to re-use the Cord 810 body, along with Hupp. John Tjaarda was given the challenge of adapting the fwd Cord body to the shorter-wheelbase rwd Graham and Hupp frames. Given the difficulties, he did an admirable job, but it was a disastrous decision in the first place. The Cord body was never designed for mass production, and the roof alone had to be welded together from seven different pressings.

Both the sharknose and the Hollywood were on tap for 1940; oddly, the Hollywood was actually a bit cheaper than the supercharged sharknose. For 1941, only the Hollywood soldiered on; until production ceased. Although the Grahams had terrible timing with their car business, the company did a booming business during WWII.

And the company went on to have a long future; after selling the company to Joe Frazer in 1944, Graham-Paige was one-half of the Kaiser-Frazier combine. By 1947, G-P sold the car side of its business to Kaiser, and went on to have a long life in other ventures, like Madison Square Garden and several NY pro teams. Needless to say, they were more lucrative than the car business ever was.

Just a week or two ago, I thought about the sharknose Graham for the first time in years. Oh well, I thought, this is one car we will never see on CC. And now this! What a fabulous find. You had to have found the only one of these parked outdoors in the northern hemisphere.

This is such a fascinating car on so many levels. But I keep coming back to the styling. It looks almost like something out of a comic book. The low stance and lack of running boards were very unusual for that era. And was this the only US car using a supercharger during this time period? I believe that it was.

I had also almost forgotten the Graham Paige connection to Kaiser Frazer. And I had completely forgotten about the Graham Brothers’ Indiana connection. Shame on me. Thanks for bringing us this seldom-told but fascinating story.

The Auburn Speedster 851, Cord 812, & Duesenberg SJ were also supercharged or available that way.

And on the other side of the pond: Bentley, Bugatti, Mercedes-Benz…. and the last Voisin, the C30 of 1938-39, which discarded the marque’s traditional sleeve-valve engine in favour of a supercharged Graham six!

Also, a bit earlier in 1937, Graham-Paige sold the tolling of the Crusader to Nissan-Datsun who continued the model as the Nissan 70 http://www.earlydatsun.com/nissan70.html

Unfortunatly, Graham in 1938 was in about the same position as Packard in 1956: The product may have been good, but after years of declining sales the market seemed to catch on to the idea that the company wasn’t all that long for this world. After the massive Depression shake-out of brands between 1932-1935 (Stutz, Pierce Arrow, etc.), the market went thru a second shake-out of the weaker remaining independents based around the 1938 recession. Hupp and Graham were the bigger losers in this round (Hupp’s history is even more depressing than Graham’s), and by 1941 the marketplace had coalesced around the Big Three and the remaining Four Independents (Hudson, Nash, Studebaker and Packard). Which is where it would remain until the 1953 sales fight between Ford and Chevrolet.

I’ve always loved the Sharknose, definitely one on the more interesting styled cars of its day. And I gotta agree about the cartoonishness of the styling. This is the kind of car I would have expected to see in the day’s Dick Tracy comic, or one of the line drawings in an issue of The Shadow pulp magazine.

Another prime bit of evidence for the concept of, “In the long run, the boring white bread cars will always win out.”

Speaking of Hupmobiles, I saw this one a few years ago at LeMay’s.

Not one of Harold’s cars. It looks as though it’s been lowered; that’s the only deviation from stock that I see. Suffice it to say that Graham didn’t have a lock on weird styling in the mid-1930’s.

That’s a (I believe, although I could be a year off) 1934. Chrysler wasn’t the only ones who got into aerodynamic design in a big way. And yes, it’s been lowered.

I find it interesting that just after the sales disaster of the Chrysler Airflow from 1934 – 1937, Graham decided to go even more far out. Hold my beer…

classic front ends

A beautiful writeup on a car I’d never seen nor knew anything about. Thanks, Paul. That steering wheel is gorgeous.

I just looked at that picture of the speedometer. Not only does the car LOOK like it is going 100 mph when sitting still, it actually IS going 100 mph sitting still. 🙂

LOL 🙂 good eye!

What a lovely car! Lovin’ the art deco feel of the grille, front lights & ingeniously incorporated taillights. very cool car and one I’d be proud as punch to own. I wonder how many parades this car sees per year.

Somehow I missed this and I was born in an era when many of these should still have been running around. When I first saw the sharknose I was struck by the resemblance to the 41 Hudson. Had to google to see the difference.

Thanks for the history lesson. A good read.

I feel that the power of the Cord 810/812 is great with this one.

I wonder if things might have turned out better if Packard had bought a second-tier independent like Graham instead of going downmarket with its own brand.

Graham had potential but it never quite achieved sufficient economies of scale on its own.

Wow. I want a model of this car on my desk, just for contemplation of its mysteries.

Incidentally, the sharknose popped up on a postwar diesel that was also striking, and something of a last ditch effort by a dying company, Baldwin:

Yes; the nose of death!

Poor, poor Baldwin. The didn’t help themselves on the RF-16 when they gave it an air-powered throttle, which meant it couldn’t lash up with EMD or ALCO diesels.

Baldwin’s inefficient DeLaVergne diesel engine didn’t help either.

Have you ever seen the M.U. connections on an air-throttle Baldwin? What a mess……

I’m rather fond of Baldwin (and Alco). They made some of the most iconic steam locomotives ever run by Indian Government Railways.

I know it would make the Concurs Restoration crowd clutch their hearts in pain but I’d love to get one of these and put an “ecobost” badge on the trunk lid.

Your life is safe as long as its ONLY the badge, and it can be removed leaving no mark of its presence. Or else.

You can see this Hollywood at the ACD Museum in Auburn, Indiana.

A nice piece, Paul. I only knew the end of the story, with the Hollywood and the company coming under the control of Joe Frazer. A neat-looking car, too.

It was the Cannonball Baker Sea to Shining Sea Memorial Trophy Dash. Cannonball Run was the name of the movie.

Righto; it was getting a bit late last night. Text corrected.

Straight out of a Tex Avery cartoon…and that’s a good thing!

Are you sure it’s a ’40? I thought 1940 was the first year of mandatory sealed-beam headlights.

If you look at the 1940 Graham brochure picture in the article, you’ll see the same headlights. I assume it is, based on the 1940 rear license plate.

1940 was the first year sealed beam headlights were legal. They weren’t mandatory at the time. Just the same, every automaker that could afford the redesign (which is to say just about everybody except Graham) switched over immediately. Live with prefocus bulb headlights for a night or two, and you’ll understand why.

Oh my ’36 Chevy shows me why sealed-beams were so nice! Because the change was so (nearly) universal in 1940, I always thought they were mandatory. Thanks for clearing that up.

Sealed beams were mandatory on US cars built in 1940. The ’40 shark nose

Grahams were unsold ’39s rebadged as ’40s. Note that the Hollywoods, that were actually built in ’40, do have sealed beams.

No, sealed beams were not mandatory on US cars for ’40, though that’s a common misunderstanding. No Federal (i.e., national) regulation of automobile design or equipment existed in 1940. There was no legal structure for any such regulation until the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966 established the U.S. Department of Transportation and three relevant agencies: the National Highway Safety Agency, the National Traffic Safety Agency, and the National Highway Safety Bureau. These three agencies were consolidated into the National Highway Traffic Safety

Administration (NHTSA) by the Highway Safety Act of 1970, but now I’m getting ahead of myself; the main point here is that it was not possible for the US Government to require or specify anything in the way of vehicle equipment or design in 1940.

At that time, vehicle regulations were left to the individual states. It wasn’t a completely random patchwork mishmash, there was some cooperation among the states via SAE and a series of associations of motor vehicle administrators. In this present example, the 7-inch round sealed beam headlamp, one per side, was standardized for the 1940 model year by voluntary industry agreement. That’s the kind of headlamp that equipped almost all 1940 models—this sharknose Graham is one of the few exceptions—and all vehicle models from 1941 through 1956; in 1957 some states began permitting the smaller 5-3/4″ round sealed beams, two per side, and all states permitted them for 1958.

In 1940, 2 sealed beam headlights were mandated by a majority of state motor vehicle regulators. State regulations had to be changed to allow 4 headlight sealed beam systems in 1958:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Headlamp

At the risk of sounding overly-didactic, the appropriate classification of the Graham’s style is Art Modern or Streamined. The practitioners of this genre were the “Industrial Designers”-Loewy, Dreyfuss, Bel-Geddes, Teague, Noyes, et al. This group applied the Streamlined vernacular to all mass-produced products, including toasters. Lord knows, there was great demand for streamlined toasters.

Art Deco, on the other hand, was primarily focused on surface ornamentation (hence, “deco”, or decorative). Probably the most recognized proponent of Art Deco was Erte (Romain de Tirtoff), a Russian-born French illustrator-designer, who was known in the US for his cover illustrations for Harper’s Bazaar and his set designs for Louis B. Mayer in Hollywood.

Thanks for that background. Streamlined design still knocks me out. This car most of all. Those headlights!

Technically speaking, Paul just called the taillights Art Deco, and it is a wonderful bit of ornamentation.

Paul, where did you find this car outside???

Parking lot for a restaurant on 99 in Eugene. There were a couple of other “classic” cars there too, so it was obviously a little get-together. But the other cars were too predictable: restored ’57 Bel Air coupe, and such. This is the only one that caught my eye.

Quite true, and I (usually) know better; I was a bit tired after working outside all day, and it was getting late. And the dog ate my homework!

Kevin: Hairsplitting here, but isn’t Streamline Moderne just a phase/type of Art Deco? The `Art Deco’ term is applied to disparate articles including the Chrysler building, and those famous toasters, even Brooks Steven’s excellent Toastalator. I’m asking as you’re in a position to clear this up for me (being a designer and all).

To answer your question, no. Art Deco found it’s flowering (ha, sometimes I knock myself out) in the 1920s. Art Moderne/Streamline followed in the 30s. Art Deco was primarily applied decoration, whereas Moderne/Streamline was concerned with form. But both were “styles”. Much of the streamlined designs Loewy did for the Pennsylvania RR locomotives were primarily for the visual effect rather than actual aerodynamic improvement. Some of these designs hampered maintenance to such a degree that the shops simply removed the decorative sheetmetal. So much for “form follows function”.

Very true. There’s a great, out of print book on the subject called Depression Modern. It was a very US response to European Modernism, but it did find some echoes overseas, especially in the UK.

Lowey did some horribly impractical designs for the Pennsylvania – Henry Dreyfuss was much more practical in his work for the New York Central – the oontrast (inside and out) between their 1938 designs for the NYC 20th Century Limited and the PRR Broadway Limited was striking – and strongly in Dreyfuss’s favor.

Beautiful cars rare as now but there is usually a pink 38 at the art deco weekend parade (absent this year) always draws a crowd.

I had never heard of or seen the Shark Nose Graham before. I think it looks awesome.

Fascinating write up on a car I was only vaguely aware of. Love the styling, especially the faired-in headlights and that taillight.

“Lean a grille a bit too far back or forwards, and folks think it’s a subversive plot” Well summed up Paul

The kind of rear legroom this car has is the stuff of my dreams, and I feel a 110in wheelbase modern car can achieve it with advanced packaging. Why it isn’t seen is a mystery. Even 120in wheelbase cars have less.

Why do you think I drive a gen1 Xb? Unparalleled rear legroom, and much less wheelbase. In fact, the whole body proportions of the Xb are not that dissimilar to thirties’ and forties’ cars: tall, narrow, almost no trunk, and gobs of interior room.

For eight years I lied to myself for the same reason. I like upright seating positions. My co-workers loved the spacious second row seating with dedicated cup holders, individual recline, and tons of legroom. But driving a soccer mom van does get old.

I’m back to where I’m really happiest. Small exterior package, large interior volume, and my friends don’t bitch about backseat room. I now drive a 2012 Impreza 5-door with a snowmobile transmission.

If your wife is an artsy crafty artist type, you might wind up driving a cube.

My wife is an artist and will graduate in the fall with her third degree, this time in painting. She drives a Subaru Forester. I have been told that only lesbians drive Subarus. This may account for her odd behavior towards me.

Or a Nissan Qube.

Check out this 1948 photo of Portland traffic. In the oncoming side ahead of the bus, it’s the landshark, looking good.

http://vintageportland.wordpress.com/2012/04/23/e-burnside-sandy-12th-1948/

Be sure and click the photo again to blow it up to full resolution, then pan around over all the detail.

Excellent eye

Did you notice that none of the cars in that photo look even close to new.

IN A WAY, i’M GLAD MY GREAT UNCLE DIDN’T LIVE TO SEE THE DEMISE OF GRAHAM.

HE WAS DEFINITELY AHEAD OF HIS TIME……JOHN NORTHUP

God Bless tour Great Uncle and his GREAT DESIGN. The Sharknose is the most beautiful design ever for a common man’s car. Talbot Lagonda for the RICH man’s wallet.

I saw one of these in the early ’60s in my smallish city in Pennsylvania, and I was like, “What the heck is THAT?” I think the styling is cool in an outré way.

The front cover of the album “Nilsson Sings Newman” (Harry Nilsson singing Randy Newman compositions) has a painting of a Sharknose in profile with a couple of the people involved with the album in it. On the back cover, you get a fairly close-up frontal view (this time a photo) of them in a Sharknose.

Now Guys….you know that is such an ugly car that no one should have to drive it….and since I am a no one, I will gladly take it off your hands and drive it so you dont have to take any insults. Just send it by mail and I will drive it all over the county just to be insulted by how ugly it is for you. LOL

I noticed that the interesting rear lights of this 1940 Graham under the trailing edges of the roof and to the left and right of the split rear window is repeated with some similarity (with a bigger rear window and less drama) in the recent Curbside Classic post of a 1972 Oldsmobile Toronado.

Whenever I see this model I think of the way cartoons tried to show speed (as Syke and Michael Hagerty commented in the first post) with the car leaning forward and with speed lines and dust shooting out the back.

If I had spent more time listening to my high school teachers and not drawing such vehicles I might have gotten better grades.

If you look at the early Batman comics you’ll see that your observations are spot on as a very thinly disguised version of this car was the original Batmobile.

In the center left of the wonderful Portland photograph is a billboard: “Stassen for President”.

Not an American, but I’ve never heard the name. Guess the other guy won.

Speaking of that “big new factory in Dearborn”, iirc it was at 8505 W Warren. Part of it still stood last time I looked. As K-F car production was consolidated at the former bomber plant at Willow Run, the W Warren plant was surplus. The government needed a place to store and show the vast amounts of production machinery that was now surplus, so K-F leased the W Warren plant to the government for that purpose. The plant was eventually sold to Chrysler who built DeSotos there through the 50s. Then, briefly, the plant was used to produce Imperials. This pic was taken when it became the Imperial plant.

Graham also bought the Gotfredson Truck Corp plant in Wayne, Mi for body production.

After the war, the Wayne plant was sold to Gar Wood and was used to produce truck bodies until the early 70s. Part of this plant still stands. It is at 36255 Michigan Ave in Wayne.

Aerial photo of the Wayne plant, which shows the massive rail facilities adjacent to it. The Ford Motor Wayne plant, originally built to produce Lincolns in 53, is just out of the frame, across the tracks on the right.

I see this one around all the time. I love the sharknose, but I could do without the customization. http://bangordailynews.com/2010/08/07/news/bangor/brewer-car-show-raises-funds-for-camp-capella/

I’ve seen it too in the Bangor area a couple of times. I’d rather it was stock too, but at least it’s out being seen and not rotting in a field somewhere.

The Graham sharknose must have been the inspiration for this moped I saw in Sinsheim, Germany:

As Graham is also my first name, I have always been interested in the Graham cars. Were they the only manufacturer in the 1930’s and 1940’s to use body shells from two other manufacturers (REO and Cord)? What is behind the silver scoop underneath the bonnet – a courtesy light or indicator?

Were they the only manufacturer in the 1930’s and 1940’s to use body shells from two other manufacturers (REO and Cord)?

Now that’s a very interesting question, Graham!

The only other car-maker I could try to propose would be Delahaye. They bought Delage in 1934 or 35, then in dire financial straits. As a cost-saving measure, Delahaye asked Citroen for its Traction Avant unibody (both in sedan and convertible forms) and adapted the smallest Delage 4 cylinder chassis, the DI 12 model, to fit the Citroen shell for the 1936 model year (pic below). The car was not a success and Delahaye-Delage soon reverted to their previous body supplier, Autobineau. It seems a few of these survived — maybe four or five.

In 1939, the Delahaye 168, which used a Renault body, came out in small numbers, most being bought by the French army as staff cars. None seems to have survived.

All the other examples I can think of are just badge-engineering (e.g. Lanchester/BSA/Daimler), or of one manufacturer using ONE (not two as per your Q) external body shell…

I’d never heard of the Citroen-bodied Delage; fascinating piece of info.

Hi Graham,

I am the owner of this Graham. It is a wonderful car to drive. Very smooth and quiet ride. It has a factory heater, radio, clock, overdrive transmission, factory split exhaust manifold, and a supercharger. The silver scoop that you refer to, is an air scoop for the defroster. It has a little heater core dedicated just for the defrost. The heater has a separate large circular coil located under the drivers side seat. Only around 7,000 sharknose cars were ever built. In 1940 only about 1,000 were sold. I have been told that very few examples exist today. Somewhere between 18 and 24 were the numbers given by the folks in the Graham club.

Tom

Wasn’t the Graham Brother’s earlier automotive endeavor Graham Bros. Truck? I think that was one of the companies Walter Chrysler bought and it became Dodge’s truck division.

Great post – I missed it the first time around. Agree wholeheartedly, the headlights and taillights on the 37/38 are sculptured works of art.

The earliest “shark” reference I could find (November 1938):

So much great information here ! .

In about 1966 one of my Brothers was living in Up State New York and spotted a Graham sitting in a field , bought it for a few hundred Dollars and made it run , a four door sedan , not a shark nose sad to say .

He told me it went quite well but needed tire or maybe brakes before he could give me a ride in it, I never saw it again .

-Nate

I remember the first time I saw a Graham car like this was in a Newsweek magazine article. I believe it was the *best* and *worst* cars of all time. This was among the worst cars. Under the photo of the car, it said “Graham “Sharknose” deserved to sink.” Whatever the hell that meant, I figured it was an awful car, either to look at, to drive, or to own. It’s not a fair judgement, since I’ve never seen one in person, nor do I know anyone who owned one. Since I’ve never seen one in person, I have no way of knowing what it was like to drive, to ride in, or what it was like.

Rolling art deco, and one of my favorite cars of the period. I’d love to see one in person–what a find to discover this one parked outdoors!

The shark-nose Graham has grown on me over time. If memory serves me correctly, it was Amos Northup’s last design before his death (an untimely one; he was 45-46 years old, slipped on ice and fell, dying from a head injury).

Graham had a long history with Dodge in regard to building trucks, too, back in the 1920’s.

Do you believe in coincidences? Opel managed to came up with a similar design for the 1938 Opel Kapitän, albeit a little more upright than the Graham.

Compare and contrast:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:1938_Opel_Kapit%C3%A4n

“By this time, it was down to one Graham; Joseph.”

I believe Ray had committed suicide in the early 1930’s – had Robert left the company by the late 1930’s?

I love articles like this because I love old cars. One thing I’ve noticed, however, is that people writing about the 1930s seem to be unaware of the “slump of 1938.” The bottom of the Depression was, of course, 1933 with the most unemployment ever and the worst auto sales for all makes (Ford and Chevy did OK because the people who in better times were buying Cadillacs, Lincolns and Packards, were now buying cheaper things, so the lowest priced cars sold “OK”. 1934 was a tiny bit better, 1935 was quite a bit better, 1936 was VERY MUCH better, and 1937 seemed downright prosperous! But then 1938 was terrible and auto sales that year were no better than they had been in 1933. There was a slow recovery in 1939-40 and by 1941 everybody knew war was coming so everybody who could possibly buy a new car bought one.

Anyway, it’s not fair to blame Graham’s demise entirely on the 1938 “shark nose” styling. It’s true that not many people liked it but every car maker found 1938 to be terrible.

“Never underestimate (an) American’s conservatism”. In some sense that changed a lot in the 1950’s, as Packard learned too late – by the 1960’s people were buying Volkswagen’s of all things in large numbers. Maybe a different lesson is – “Americans won’t buy something perceived as a desperate measure, no matter how good (and especially if flawed)”, as Studebaker learned with the Avanti and Packard learned with the 1955’s and 1956’s.

A genuinely very original and creative design, that was unique, and quite attractive. And deserved to be embraced, and successful. But as has been shown through history so many times, so many people would rather conform with millions of others, than be seen as individualistic, and groundbreaking in thought. Conformity being a source of security for many, afraid to stand out and be noticed, with something different.

One of my first lessons in this as a kid, was in the song ‘Freedom of Choice’ by the alternative group Devo. Thought provoking social commentary.

“Freedom of choice is what you’ve got, freedom from choice is what you want.”

My father had a Hollywood Graham at some point, which he picked up in the 1950’s for a song as a teenager. He spoke of it with affection. If I remember Graham used Continental engines, the same as did Kaiser-Fraser (which makes sense because of the G-P/K-F lineage) and Checker.

Some mention of the advisability of a Packard/Graham merger/alliance, but Packard came out with their own six, the 110, to complement their small eight, the 120. The lesson of the “Clipper as a separate marque” saga in 1956 was that the mid-range Packards sold because they were Packards more than anything else, and so slapping the Graham name on a Packard would not help matters, and as the 110 and the Graham six were direct competitors, with Packard needing the volume at it’s own plant to maintain profitability, Packard providing, say, engines to Graham wouldn’t make sense either. Customers in the 1930’s understood the difference between a “junior” and a “senior” Packard, with the latter providing the prestige needed to sell the former. Too bad the management of Packard postwar lost sight of this simple fact.

What Packard desperately needed as the 1940’s came to a close was an automatic transmission, a modern (V8) engine, and a functioning styling department. They got all three, but lagged on the latter two until the 1950’s got going, and by then it was too late.

Some mention of the advisability of a Packard/Graham merger/alliance, but Packard came out with their own six, the 110, to complement their small eight, the 120. The lesson of the “Clipper as a separate marque” saga in 1956 was that the mid-range Packards sold because they were Packards more than anything else,

My sense is the problem with Clipper was that it wasn’t established as a brand. There were plenty of established brands that could have been acquired.

Packard had significant opportunities to acquire an established mid-market brand over the years.

They could have bought the Auburn brand when the company went into liquidation in 37

Nance established two strategic objectives when he took over at Packard: 1: establish a stand-alone mid-market brand, so he could move the Packard brand upmarket, and 2: bring body building in house.

Hudson was an established mid-market brand, and owned a body plant, when Ed Barit approached Packard about a merger, and was brushed off. At the same time as Barit was shopping Hudson, Walter Briggs had died and the word had to be on the street that the Briggs heirs were shopping the company. The whole world wonders what Nance was doing, while the future of his sole source for bodies was in doubt, and another body plant offered itself to him in vain.

Studebaker had been a mid-market brand before the war. They could have merged with Studebaker, with the President and Commander badges used on the cars we know as Clippers, instead of their being fancy trim versions of the uncompetitively narrow Champion body.

A clarification to my comments above. 18 to 24 existing examples of the 1940 model year.