(first posted 3/22/2012)

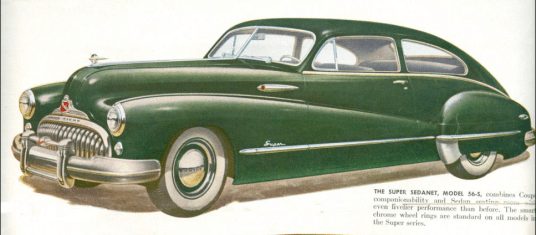

This Buick has so much going for it: a killer grin, a svelte long hood covering a genuine straight eight, a delicious aero-back tail, and the kind of delightful chrome details that can keep ADD eyeballs glued to it long enough to test the patience of even the most tolerant spouse who found it and led you to it. Buick’s 1942-1948 styling was generally as good as it got in the World of Tomorrow. But there’s just one thing missing here which would have elevated this car to true legendary status and a GM’s Greatest Hit.

One could well argue that the Buick division was GM’s Greatest Hit ever. Well, it was the origin of the whole company: all the other divisions came later. Buick really was the core of GM, and its consistent best seller after budget-brand Chevrolet. As such, it was only right that Olds and Pontiac took the axe; they were just johnny-come-latelies, mucking things up for Buick.

In 1936, Buick created one of the all-time most significant American cars ever, a highly-worthy Greatest Hit. By dropping the big-block 320 inch straight eight from the large and heavy Series 80 and 90 cars into the relatively lithe Series 40 body, Buick created the first American muscle car, using a formula that would be replicated so successfully with the 1964 GM mid-sized cars. It was given the name Century for a very good reason: it could readily hit and maintain that speed, something unheard of in a mass-produced and relatively affordable car.

Weighing a mere 3200 lbs and packing a solid 120 hp, the 1936 Century had a better power-to-weight ratio than all-too many cars from the seventies and early eighties, including Buicks. It was a brilliant idea, and enhanced Buick’s reputation further, as if it needed it.

A cornerstone of all Buicks was its strict adherence to overhead valve engines, at a time when flatheads were still typical, and the staple of Olds, Pontiac and even Cadillac. The Buick straight eights were already legends in their time.

With their much better breathing, Buick eights were some of the most popular engines in the early hot rod era. As it was, they made pretty good power in stock trim. The big 320 incher ended up with 170 hp in its last year, 1952. The modern Olds OHV topped out at 160 hp that same year with a four-barrel carb. No wonder Buick took its time with its own new V8, the legendary nailhead.

I’m getting all worked up about the big-block eight because it’s missing here. Of course it wouldn’t be in the actual Special, but for some reason, Buick dropped the big-block Century version after WW2. This is a 1941 version; it was still available as late as 1942, when it looked virtually identical to the 1948. But gone it was, starting with the 1946 model year.

In fact, Buick flipped their whole line-up. Instead of the Series 60 Century having the small GM B-Body and the big engine, now the mid-range Buick was called the Series 50 Super, using the big GM C-body, but the small 248 inch eight as in the Special. Where’s the fun in that? Kinda like a small-block Wildcat, instead of a Skylark GS 400.

The Century came back for 1954, with the new V8 in the smaller B-Body, and restored the rightful order of all things Buick. OK; you’re going to say it’s not the Special’s fault that there was no Century between 1946 and 1953. True, and yes; the Special was certainly a handsome and fine car.

But truth be told, the bigger C-Body Buicks really were better looking, with their fully faired-in front fenders and more flowing lines.

The differences between the B-Body Special and the A-Body Chevrolet are real, but take a bit of close examination to pinpoint. Some parts, like the front doors, look almost identical. Might they be? But the A-Body was shorter, meaning the roof had to be humpier to leave enough head room for the rear passengers. And the Chevy rear side window is bigger. And there’s a number of other minor but obvious other differences. And of course, the Buick sits on a longer 121 wheelbase, much of that being taken up by its long tapering nose. That all adds up to subtle but definite improvements in the Special’s proportions.

While we’re comparing the Special to the Chevy, let’s consider that the step up from it to Buick’s most affordable car was $300 then, or a 21% premium. The Special’s asking price was $1735, which inflation adjusted makes about $20k in 2021 dollars. Actually, I don’t put a lot of stock in inflation adjusted figures when going back that far, because so many other factors can skew it, most of all the change in real purchasing power during the fifties and sixties.

And what exactly did that 21% premium buy? Most of all (as usual) bragging rights: the Buick name, and that hungry mouth inspired by Harley Earl’s famous 1938 Y-Job, the mother of all GM dream cars. A slightly longer wheelbase too, and of course the straight eight engine, although in the case of the Special, it was the smaller 248 inch version, making 110 hp, versus the Chevy’s ohv six’ 90 hp.

And of course, Buick’s fine hood ornament, which certainly outclassed the Chevy’s.

But no portholes, though (that tapered spear on the hood is the release to open it, unless I’m mistaken). Those Buick trademarks were only one year away, appearing on the all-new 1949 bodies. Which reminds me: 1948 really was the end of the line for this generation of Buicks, both the Special and the big Super and Roadmaster. That was odd actually, because Cadillac had already switched to the all-new C-body for 1948. The dance of the divisions wasn’t anywhere nearly so well coordinated as they would be later in GM’s evolution.

Time to tear ourselves away from that most handsome of GM’s faces of the time. The back end of this aero-back Sedanet is of course appealing too, except in comparison to the even more seductive one of its big brothers. In fact, from here, one would have to be a bit of a GM expert of the times to readily tell which of the (non-Cadillac) divisions this car is from.

I’m sure if you were young in 1948, you’d have recognized the bright red Buick badge on the back. But what’s that just below it?

Dealer identification has come a long way from this custom made one from the St. Paul Buick Company to the license plate protectors of today, which I don’t even see very much anymore hereabouts. Tasty.

Let’s take in this rakish attitude one more time, and imagine what an eminently desirable car this would be with the big 150 hp engine under the hood. Although weight was up a bit since the original 1936 Century, this Special was listed at 3625 lbs. Add another hundred for the big block, and you’ve still got a very modern-ish power-to-weight ratio. This coulda’ been the bomb.

As long as it didn’t have the all-new for 1948 Dynaflow (“Dynaslush”), the true origin of the slushbox moniker. It wasn’t available on the Special or Super anyway, as their smaller engines would probably have been sapped too badly under the losses that the one-speed “transmission” imposed. We’ll do a more detailed look at it when we do a CC on a Dynaflow-equipped Buick. For now, imagine dropping the long shift lever into first, giving the big 320 inch compound-carburated eight some throttle, and stepping off the clutch briskly. An imaginary 1948 Century would have been by far the hottest American production car available; let’s call it the 1948 Buick GS 320.

And unlike the muscle cars of the sixties, there was no penalty for riding in them, especially the rear seat. That’s the benefit of that tall body, which would soon give way to the lower-is-better mania.

We’ve come full circle, of course. At the time I was shooting these pictures, I was annoyed at that new Subaru Outback next to it, but now I realize it’s a perfect example of how body height has come back to 1948 levels. They’re almost identically tall. Asa tall person, that’s the best thing that’s happened in decades.

“Just one more second, honey! Come check out these wipers!” I’d forgotten about the pedestals these thing sit on. So how exactly does the wiper mechanism/linkage on these work? Sure looks awesome. It’s little details like this that can push a person into quitting writing about old cars and actually getting one.

Speaking of, this car was parked downtown by the city utility offices, and was obviously driven to work that day. And its interior looks mighty original, including that hole in the driver’s side door upholstery; someone’s elbow too long and pointy? Well, this is a holy car, no doubt about it. But just not quite enough to push it into Greatest Hits territory. That requires genuine sainthood, and without that big 320 inch motor under the hood, this Buick is merely…very Special.

Just the other day, I was looking at a 46-48 Chrysler coupe and thinking how graceful it looked from the rear. This Buick reminds me that the K. T. Keller era Chryslers weren’t really very graceful at all. This Buick coupe is absolutely beautiful, both inside and out. GM really defined what a car was supposed to look like in those years.

I have often described the GM of the 1960s and 70s (and beyond) as an arrogant company. But after about thirty years of building cars like this, I suppose some arrogance is to be expected. In this Buick, GM built one of the best cars in the world in 1948. And to think: some lucky guy gets to drive this car home from work in 2012. I would absolutely love the experience of a silent Buick 8 being driven through its torque tube.

One more thing: we can dog Buick all we want for only putting the small 8 in the Special, but remember that you had to go all the way to a New Yorker to get 8 cylinders out of any Mopar. And other than a Chrysler Windsor, did this car really have any competition in the US? I don’t think that either a Nash Ambassador or a Hudson Commodore had the same stature. I would imagine that this ohv 8 cylinder Special would run rings around a flathead 6-equipped Windsor (before even considering Chrysler’s inefficient Fluid Drive.)

Fabulous car, Paul. Thanks for presenting this one to us. I don’t imagine that we will hear any complaints about this one not being “classic” enough. 🙂

The quality of these cars is so impressive, I’ve had the chance to play around with a few of them, through 1955 at least, the way all the doors and hood and trunk close is awesome, you can close the door with one finger, or just hold it like 8 inches away and let it go, it will just latch itself, you dont have to “slam” anything on these Buicks.

In 1968 (then I was 7 years old) I used to go to my piano classes every afternoon, Monday to Friday. One day I glanced through the back window of my father’s 1965 Fiat one of the most impressive sights I’ve have ever had in only 7 years of life, and it was a beautiful 1947 or 48 Buick Sedanette, as the one shown in the picture, I remember the roof painted in white and the rest of the body in blue sky hue. Well, many years passed, as you can imagine, and recently, about 6 months ago, I saw it again! Forty fours years later the car still survived (as in a Cuban postcard) but sadly, its rear was chopped to make space for a pick-up box, and I almost died the minute I saw it. Of course, the first time I saw it was in an upper-class neighborhood, but lately, I found it in one of the slums in the outskirts of the city. Too sad an image, too good a memory!

Stunned at the sheer beauty of this vehicle. i nominate this as the CC poster child. Any second that?

I’m kind of attached….

I’d say its a Greatest Hit just how great it looks. “Almost push a person into having an old car like this”

Almost? I’m ready to bring cash to OR and buy it right now.

So when will we see the 1954 Century Greatest Hit Article?

When I find one!

I got to talking to the owner of a similar 1948 Super sedanet. He ended up asking if I would take him for a ride in it. He’d always driven it himself since it was restored, and never experienced it as a passenger. Well, it was smooth, slow, and stately with the Dynaflow, and had the expected 1948 GM road manners. We were both happy after the drive – it’s the only one of those I’ve ever driven.

To me the slanted B pillar of the Special body is the biggest difference – that and the taller appearance of the windows. That surprises me, in that my first car was a 1947 Chevy with that same fastback body, and driving it seemed like looking out of a cave. It’s probably a good thing that I didn’t need to back the gentleman’s Buick Super out of a garage space.

cool aint it

When I was young I drove a 1946 and then a 1949 chevy. The kinship with the 49 is there for anyone to see. Sure is easy to get to liking cars like this.

Cars of the 1940s speak to me more clearly than those of any other era. It’s not just the style, it’s the smell, the scents of cotton and wool and steel overlaid with whiffs of oil and hot water. Fortunate indeed is the man who drives this on a daily basis.

Just a nice old car.

I could really enjoy doing a resto-mod on one of these and then driving it every chance I got.

agreed! A bit like that Black ’48 Roadmaster’ — very sweet.

Well I could really enjoy driving an all stock version, jack.

When better cars are built Buick will build them. Gorgeous car Paul what a great find Ive always loved the aero GM models of the 40s telling them apart Taillamps is the key. The new height cars are growing to now is a good thing I have 2 cars of very similar size but the 59 is easier to get out of I must be gettin old.

A stately car and the respectful writting certainly does it justice. Thank you.

Just a thought wasnt it David Dunbar Buick who thought up overhead valves? Neither Buick or Chevrolet ever used sidevalve engines, that was a piece of dogma drummed into me from just after birth.

What a great read after a long day…excellent, informative write up!

I’ll go out on a limb and suggest the 1938 Y could be the most beautiful (ok, top 5) auto designs ever.

Beautiful car, Paul. This was the high point of GM, up to the Korean War. It was at this point that GM found out it could get away with “Korean Chrome” and the beautiful workmanship slowly eroded until we hit the X-car Skylark. However, in 1948, GM was really better than anything in the world.

I had the, opportunity, many years ago, to drive a 1947 Roadmaster. The car was supremely well built and the Straight 8 made prodigious torque. The Torque-Tube drive meant there was practically zero driveline lash; you could lug it down to walking speed in high gear and it would not miss a beat. These cars were all about smoothness and stately driving so any attempt at cornering is basically useless but that is not what a Buick was about, something they are missing even today. Buicks are for old men. There are lots of old men out there. Trying to peddle them to people who buy (or more accurately lease) 5 Series BMWs is absurd and will mean the death of the brand, just like Oldsmobile.

And Paul, it is one thing to photograph old cars; owning them is another. Takes lots of time and deep pockets.

> Buicks are for old men.

Stereotypes, stereotypes. Not to mention the prevalent stereotype of the BMW 5-leaser. Of course, in some professions the *appearance* of age and understated wealth is a plus, and clients tend to trust young flashy folk less. This would include doctors, attorneys, and bankers. You know, they people who buy plain, unadorned Rolex watches, generic-looking blue/gray/brown Savile Row suits, and Lexus cars. They can *afford* MB as easily as Chevrolet, but they won’t buy ’em. MB is too ostentatious, while Chevy’s too downmarket. These guys earlier used to buy Olds and, you got it, Buick. Its a good strategy, really, to push Cadillac at the BMW crowd, while shore up the traditional luxury market with Buick. 8-cylinder RWD land-yacht anyone? That leaves GM with nothing to compete with MB’s top line, but Cadillac has never competed with that anyway. Time to buy Packard, GM?

>…And Paul, it is one thing to photograph old cars; owning them is another. Takes lots of time and deep pockets.

You’re absolutely right. That’s the only thing keeping me from going out and buying a straight-8 Roadmaster, and a OM312 6cyl diesel truck, and… well one can dream.

What a lovely old car!

I hadn’t noticed the hand straps affixed to the back of the front seats. What a great detail! And that dashboard, wow! It reeks of America at it apex!

I can’t take my eyes off this car. I had to forward the link to my Dad– he’ll get a kick of this and the entire write up, actually.

The love really shines through, Paul!~ great job!

We had a ’48 Pontiac slant back, long wheelbase, straight eight flathead when I was a kid. Pretty much the same body as this Buick. We had it in ’54 and maybe ’55. All I remember was that it was a real tank and swilled gas. Sharp looking, tho, in black.

The ’48 replaced a ’38 Pontiac 6 cylinder 4 door sedan that had been a hand-me-down from Grandpa when he bought a new Pontiac in ’51. He had long been in the habit of buying a new Pontiac, (or its equivalent Oakland before that), every 12 or 13 years. Just like clockwork. Evidence that if you took good care (he always washed his car every Sunday, regardless of the weather) the older cars would last well beyond the typical 3 year trade cycle. (This 64 year old Buick seems to confirm that in spades).

Part of the beauty of this car is the two tone paint. It would be interesting to see a manufacturer bring back mulit-color paint schemes.

You can really see the styling influence the 1941 Buick had upon the Volvo P544!

The ’42 Buick was also a huge influence on the 1948 “Stepdown” Hudsons.

The front surely brings back memories. Suffice to say that the rapturous experience Paul had with the Cadillac in Austria was, in my life, due to a Buick Roadmaster. I *knew* it was a fine car when I saw it, and I knew nothing about cars (or anything else) at that time. B.U.I.C.K. That’s what I called it. Oh boy! To this day I maintain that cars with long hoods better have straight 8s in there, or else they’re just fakes. My respect for V8s as luxury features is vanishingly small.

Originally, Buick was supposed to have the new C-body for ’48, also, along with the Cadillac and the Futuramic Olds 98. However, at the last minute, Harlow Curtice developed reservations about the new nose and grille treatment and asked new Buick chief stylist Ned Nickles to redo them before launch.

The new C-bodies were very late anyway, so the new Cadillac and Olds bodies didn’t arrive until around February of 1948. At that point, even a few months’ additional delay was enough to push the Buick to the fall and the ’49 model year. The 1950 model (actually designed earlier) wasn’t changed, so the ’49 ended up a one-year car. (I talked about all this in the article I did last year on the ’49 Roadmaster Riviera hardtop.)

The postwar Super may not have been a lot of fun, but it was popular — apparently a lot of people liked the idea of having a big Buick to wow the neighbors, even if it meant taking the smaller engine. Buick took that a step farther in 1950, offering both the standard Super and a bigger Super Riviera (pillared) sedan that was about as big as the ’49 Roadmaster. It was once again a huge success, so I guess they were onto something.

I absolutely love the Buick, and what a fine example of true workmanship of the classic Buick you have. I own a 1951 Buick Super and already she has attracted a lot of interest. These cars are graceful and have oodles of style. Thank you for your very interesting read.

I see and admire this car at least several times a month when our walking group goes by the EWEB parking lot. I hope the person who owns this car keeps his/her job in the present building and doesn’t move to the new place in west Eugene; I would miss passing by this beauty!

Back in the 60’s i owned four different buicks, My favorite in that time was my 54 which was the same as the one you have featured here same color, standard transmission and a 264 nail head v8 and a hard top. i sold it off when i got drafted in 66 and have never seen it again. Love them Buick’s.

I hate to take away from a great Myth , but the early Buick Century’s were more known for wildly optimistic speedometers than real speed , I remember an English magazine (Autocar ?) publishing a test that said at an indicated 120 m.p.h. on the speedo , the Century on test was doing 87 m.p.h. as per Stopwatch … a contemporary test comparison by Packard between the 120 and the Century , had them both timed at a top speed in the late 80’s , (I think the Buick was marginally faster) . I don’t think there was a normal mass produced American car capable of 100 m.p.h. until the 1949 Cadillac with its light 160 hp engine .Still , the Century was a great car.

Hard to tell for sure in that magazine ad, but it might be (and you may have owned) a ’54 dressed up in one of the popular Buick pastel colors of the time: Gulf Turquoise Green. My first car ever that I bought from my uncle in 1982 was a ’55 Buick Special 4dr with a Dover White top and Gulf Turquoise body. Paint was original and only slightly fading in a few spots…

Thanks for spotting my grandfather’s 48 Buick in the EWEB parking lot in Eugene, Oregon. The car lived it’s first 58,000 miles off Snelling Avenue in St. Paul, and when my grandfather passed, my dad flew back and bought it from my grandma. He drove it home, using about 12 cans of oil along the way, and once in Eugene it was covered and, well, not driven. My father passed four years ago come Feb15, and we all miss him. Unlike my father and grandfather, I drive the car, a car that is named “Gracey” after my grandmother Grace, who was about 4′ 9 100 pounds and most likely was not ever able to drive the car. When I drive it folks just smile and wave, and dozen of folks who were driving in the 40’s walk up, smell the inside, and tell me an awesome memory that puts a little zip in their step as they walk away. So again, thanks for seeing Gracey and snapping a few photos of her.

Dan; my pleasure. What a fine car, and what memories. Enjoy!

Given 1948 I’d prefer a Hudson Eight w/overdrive over Buick Special.

Better road manners, larger interior, more mpg, and faster.

Altho flathead, Hudson eights achieved higher hp/cubic inch than overhead straight eight Buicks except possibly 320 cube late pre-war w/twin carbs.

Which is the power of the engine and the maximum speed of the Buick series 40 1948

My dad owned a 1949 Buick special. After he traded it in on a newer car in 1970 his brother that was in a old Buick club told him there was only 400 made in and sold as 49’s with body’s that were leftover 48’s so it was a very rare car. My uncle owned over 100 Buicks older than 1959 with his preference for 1930-1948

So THAT explains it…I skimmed the 1941 Chevrolet item but when I went back into History to read it some more, it had gone “404.”

Waiting for its return…

Great Re-CC!

Curbside Classic, where even the reruns are tasty! 😉

This article got me to wondering… aside from both being OHV, were there any other strong similarities between the Buick and Chevrolet engines?

Just finished the autobiography of Gerhard Neumann, a genius mechanic during WW2 who went on to be a GE executive. He became famous in China for his abilities at fixing P-40s & cars despite lack of spares, & of course some of his clients drove Buicks. After he changed the distributor advance on a brand-new but rough-running ’40 model (he identified the cause as bad fuel & slow driving), its prominent owner couldn’t thank him enough & gave him several hundred US$ plus his 1939 Peugeot. BTW Neumann said American cars were better than German during his garage apprenticeship in the ’30s.

Thanks to a gifted north-Chinese blacksmith (& his wife who could brandish a sledgehammer when not nursing her baby), he was also able to produce a replacement Ford front leaf spring for a British consulate employee. During the Chinese Civil War, he & his wife drove all the way from Thailand to Palestine in a Jeep.

Thanks for re-posting this article. It’s a great car and a great write-up, especially with information from the car’s owner. As a member of an orphan car family (happy 100th to Nash), I’m finding that Buick might offer enough tradition and style to be a surrogate–if a decade or two of mediocrity are excused.

These are the cars that made Buick famous and the American consumer the envy of the world. That green ’54 Century hard top coupe, ( My favorite car design ever!) that would be automotive Nirvana !

My parents had a (hand-me-down) 1955 Special convertible for many years, including most of my childhood, to college age. It was a great looking and very cool automobile in two-tone (aftermarket, so my father told me) green with a two-tone green vinyl interior.

I did get to drive it a few times, too. It was great fun to drive.

I had to magnify the pic of the Buick emblem on the trunk to see the dealer’s name engraved on it. Very nice!

I always liked the front clips on these Buicks. They gave the car a mean, angry look.

Late comer ? The 1902 curved dash Olds was the first production car made in the US.

Latecomer to GM. Durant started with Buick in 1904; Olds was added on 1908.

Buick was the basis upon which Durant used GM stock to buy Olds and the other companies that made up GM. And Buick became its most consistent profit center, until eventually Chevrolet’s vast volumes made it the biggest profit generator in GM.

But for quite some decades, Buick was the “backbone” of GM. Which explains why it had so much relative autonomy, and why Harley Earl used Buicks for most of his early dream/show cars, like the Y-Job and LeSabre.

Compared to Buick, Olds was small potatoes until well into the 70s. Pontiac too, until the early-mid 60s.

After the war the redesigned hood ornament was commonly referred to as the “gun sight hood ornament”.

Bombsight, I believe.

http://losangeles.buickclub.org/PDF/BOMBSIGHT-2010MARCH.pdf

I can see either way, but more a gun-sight as you looked horizontally down the length of the hood vs. vertically as in a bomb sight.

The worn fabric on the door panel reminds me of how you used to see this on every old car of this era if it was an original. The combination of water stains and wear areas was ever-present with the natural fabrics used then.

I remember thinking about panels like these when I got my Honda Fit, which uses fabric that matches the seat upholstery on the upper door panels. A lot has changed in the intervening decades, because neither the seat upholstery nor the door panel shows the slightest bit of wear.

In 1970 my dad had a 1949 Buick Special, he had it for a couple of years. He was driving it about 60 miles back and forth to work so he traded it in on a Datsun for the better gas mileage. Shortly after he was talking with his brother who owned over 200 old Buicks at the time who informed him that the “1949 Special” was very rare made with left over 1948 bodies and worth more than his new car. I think that was the only bad car deal my dad ever made, but it was terrible.

It had no dents, the upholstery was good, and it was indeed a dependable drivable car in 1970. I remember how that car looked and the looks I got when I drove it to school when I was 16 a couple of times.

I know for years the 1946-48 American cars were at least somewhat overlooked because of their being “warmed over” 1942 models. But darn it, I’ve liked them for as long as I can remember! This wonderful 1948 Buick is stunning…..