(first posted 1/5/2012) It’s one thing to be graced with the most beautiful and forward-looking design of its time, being no less than the forerunner of every personal luxury coupe to come. It’s quite another thing to know how to actually build it and capitalize on it. The 1953 Studebakers were the last real opportunity to turn the foundering company around. Rarely has the expression “to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory” applied more fittingly and painfully. If it weren’t for the sheer thrill these cars still impart sixty years later, one could almost wish that the whole sad episode had never happened. But it did, so we’ll just have to buck up or get out the kleenex.

Only Studebaker could have built these cars. The Big Three would have laughed at the idea of building coupes with bodies completely unique from their sedan counterparts. And with such European flavor too. Heresy! Maybe a token roadster, like the low-volume Corvette or T-Bird, but those were really just halo vehicles in their early incarnations. And GM and Ford could well afford to lose a few pennies on them.

Chrysler kept churning out exquisite coupes, collaborations between its styling head Virgil Exner and Ghia. Those that were actually built for public consumption were strictly for the 1%. Except for their very brief dalliance with the Nash-Healey, AMC stuck to bread and butter sedans and wagons. There wasn’t any Rambler coupe for many of those years.

So what was Studebaker thinking, literally betting the company on a low-slung, very European coupe? Richard Langworth, author of “Studebaker 1946 – 1966: The Classic Postwar Years” summed it up this way: “If in 1950, executives had decided to put Studebaker out of the car business within the next fifteen years, they could hardly have gone about it in a more efficient way”.

Jim Cavanaugh covered the first main postwar chapter in his 1949 Land Cruiser CC, when Studebaker enjoyed record sales and profits in the post-war buying boom. As that receded, Studebaker faced an enormous existential crisis: to compete directly against The Big Three, or carve out niches in the increasingly competitive market? Or better yet, both!

That decision was partly made when Raymond Loewy, who’s firm had the contract to provide design services to Studebaker, came across a design that Bob Bourke had been working on for some time. Bourke envisioned it strictly as a show car, something along the lines of GM’s Motorama dream cars. But Loewy latched on to it, as it fully embodied the primary values he had been preaching for decades: slimness and grace. And although no one denies Bourke’s authorship of the Starliner coupe, without Loewy’s tutelage, patronage and most of all his ability to sell progressive ideas to a conservative management, it would have just ended up as another page in his portfolio.

Bourke’s coupe sat on the extra-long 120″ wheelbase Land Cruiser frame, to give it additional sweep and a long and graceful tail. Perhaps an odd choice, since more typically coupes often sit, if anything, on shorter wheelbases than their sedan counterparts. The decision to do so would be one of many that would haunt the ’53 coupes. Aesthetically, it does feel a bit extended, and I would love to see someone do a shorter version via photoshop.

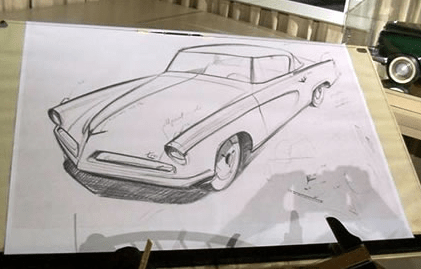

Loewy designer Bob Koto was also invited to work on the development of the coupes, and he and Bourke shared one full-sized clay, each side reflecting their specific solutions to bringing it to fruition. Here’s a picture of Koto’s side. Loewy chose Bourke’s, and that part is history. But also just the beginning.

The coupe was a radical departure from the norm, especially for 1951, and Loewy fought an uphill battle in getting management approval. The board went back and forth, but Loewy’s vision for Studebaker espousing a decidedly European approach to design principles, which also reflected his mantra of smaller, narrower, and lighter, had powerful influence. Studebaker’s compact 1939 Champion, which Loewy designed, was the first, and all Studebakers since it were consistently narrower and lighter than the competition.

It also presented Studebaker with a fundamental challenge: to sell smaller cars for more money. Studebaker was very lazy with their union negotiations, fearful of confrontation and strikes, and keep the old-school chummy atmosphere. This led to Studebaker having consistently higher hourly and unit costs than the Big Three, ultimately perhaps the single biggest contribution to their demise.

In light of Studebaker’s market position, and the crushing ability for the Big Three to flood the market with discounted cars (as it did in 1953) Loewy’s hard sell for the ’53 coupes certainly carried some logic. If anything, Studebaker’s mistake was to not embrace the coupes more fully. It might have been hard to imagine that personal coupes would come to be the best selling cars in the land, as the dominance of the genre, and the Olds Cutlass Supreme showed so convincingly in the seventies and early eighties. But then drivers have always fallen for the allure of something more stylish and expressive than a dull sedan. That was already known in 1953, as it was in 1933 and 1973.

It’s well know that the ’53 coupes suffered from horrendous production problems and delays, as well as build quality issues. Doors wouldn’t open or close, there were huge panel gaps, Studebaker’s notorious rust issues were worse than ever, and behind the scenes, there were logistical production nightmares. Studebaker was simply not prepared to build two distinct cars, and it was the coupe that suffered disproportionately.

The reason being because the 1953 sedans were really not all that different under the skin from their predecessors. Which may have helped them avoid some of the build issues, but it created a whole other set of even bigger problems. They were essentially afterthoughts, and it showed. Instead of being original creations in their own right, a dollop of coupe styling cues were grafted unto a rather dumpy and charmless body. And their very weak sales reflected that. It didn’t have to be that way.

I’ve been in contact with former Studebaker (also Ford and Chrysler) designer Bob Marcks, who has forwarded me these sketches of how he thought it could have been done, with the sedans sharing the coupes’ bodies, resulting in (relatively) minor differences in the doors and roof. Given the coupe’s long wheelbase, there certainly would have been enough room to accommodate the extra door handily. In fact, it rather looks almost more balanced than the coupe.

Bob even had a model built from the sketches, the Starliner sedan. Nice.

I’ve always felt Studebaker got these two cars backwards, but then Studebaker used to be known for their coming-going issues. This long-wheelbase sedan, and a slightly shortened coupe might have been the real solution. But then everybody likes to armchair Studebaker to death.

Marcks also has some pithy insight on some of the many production (and other) problems with the ’53 coupes.:

First, Studebaker had let the unions write a contract which made the cars substantially overpriced; so they weren’t competitive for value. To compensate, the company took quality shortcuts: too much friction in the steering mechanism, weak frames, small brakes and other minor weaknesses.

Even worse, to reduce the initial tooling expense, they listened to an engineer who had a radical plan for reducing tooling costs. New dies for body panels are very expensive, to make a fender, for example, you can’t take a flat sheet of steel and stamp out a fender. It has to be done progressively; bent slightly, then into another die to bend and stretch it further and so on until the final die produces the final shape. Bend too quickly and the steel wrinkles or even splits.

A so-called “expert” persuaded Studebaker that he could save them tooling money by eliminating certain progressive dies. In a word, his plan was a disaster; he miscalculated and couldn’t produce panels which didn’t wrinkle and split. New dies had to be produced hastily and production was delayed. Orders couldn’t be filled, so customers, momentum and profits were lost forever. The public wasn’t aware of behind-the-scenes problems; the appearance was that the new Studebaker wasn’t popular.

So the outcome was a nightmare, and one that Studebaker never really recovered. In 1952, coupes made up some 27% of production. Studebaker assumed that would roughly continue. With the new coupes that changed to about 50%, by far the highest take rate for coupes in the industry. And that’s with production snafus. As Loewy had warned, the dull ’53 sedans not only didn’t ride the coupes’ coattails, they utterly fell into the gutter.

The result was a double disaster. And one which forced Studebaker into increasingly desperate measures to survive, the first being the ill-advised “merger” with Packard, which did nothing for Studebaker, and killed Packard. The only thing that kept Studebaker alive as long as it did was the little bounce it got from the 1959 Lark.

Yet “Loewy coupes” are clearly the prophets of the whole personal coupe market that was to sweep the land just as the last of the Studebaker Hawks were going extinct. The 1958 Thunderbird was the opening salvo in that massive wave, but a bit too pricy for the mainstream buyer.

The Corvair Monza, another eventual failure, definitively proved that Americans’ appetite for sporty coupes was very substantial. And the hunger for the Mustang was almost insatiable. But the T-Bird, Monza, Mustang were just the bookends.

When John DeLorean re-invented the 1969 Pontiac Grand Prix as a luxury/sporty mid-size coupe, and a quite affordable one, the formula that came to dominate Americans’ driveways was perfected. And what was that formula again? A mid-sized sedan frame extended to accommodate the longer hood and revised seating position, all done for the resulting long, low and sweeping good looks. Exactly the same formula as the ’53 Starliner coupe.

[The featured car is a 1954]

I’d love a framed copy of that pencil sketch – it must have wowed even the most blockheaded executives. Who could say no to such a pretty thing? Sounds like the cars didn’t really do it justice.

I should add he drew those sometime in more recent years, a kind of “what if” scenario. Marcks didn’t start at Studebaker until after the ’53s were already a done deal.

Also, if you click on that sketch, it will come up in a substantially larger size.

I have one that I am trying to sell, I have the title and all 12,500 original miles. White top instead of the black.

A fabulous find! The 1953 Studebaker may be the ultimate triumph and tragety story of the U.S. auto industry.

You hit an important point, in that the coupe was a completely different car from the sedan, and Studebaker was ill-prepared for the production problems that this brought. That this coupe could serve as the basis for a modestly competitive product ten years later (the G T Hawk) speaks to how radically low the car was in 1953.

I have always counted it a tremendous shame that the willowy frame used on this car put the kibosh on a convertible (which had been a regular part of the lineup in the 1947-52 series). A stouter frame would have cured many of this cars problems, and a Commander Starliner convertible would have been a stunning car.

I had understood that the 53 sedan was not so much an afterthought, as a project that was hijacked at the last hour in an attempt to incorporate the coupe’s styling cues. The 1953 sedan had been in the planning stage for some time, as the 1947 body was in its 6th year by 1952. However, I am not sure that I have ever seen any pictures of the original proposal. But it had to have been better looking than what resulted. Still, the tall, stubby dimensions (that were not so uncommon in the industry at the time) would not have stayed in fashion for long.

It is a shame that this car’s owner felt the need to slap fender skirts on this particular example. Although I like fender skirts much more than the average bear, I do not think that they look good on this car. But still, how often are these seen in the wild today? You have made my day.

The 1953 models were supposed to debut for the 1952 model year, as part of Studebaker’s centennial celebration. They were originally dubbed “Model N” within the company. The radical coupe sketched by Robert Bourke changed these plans. The need to tool for the coupe, along with foot-dragging by management, pushed the debut date to the 1953 model year.

A magazine ran some photos of discarded Studebaker prototypes and styling studies. Apparently, when Studebaker was done with them, it simply tossed them onto wooded company property around South Bend. There were also some photos of styling studies for the original Model N proposal in either Langworth’s book or an old-car magazine in the late 1970s, if I recall correctly.

The sedans, as originally proposed, weren’t bad looking, but they weren’t earth-shattering, either. They probably would have sold better than the sedans that were produced in 1953.

Author Tom Bonsall made an interesting proposal. He suggested that Studebaker should have kept a facelifted version of the 1947-52 model in production for the sedans, and offered the Starliner and Starlight as a separate, new model. The old body was modern enough to have remained competitive with a facelift. This path would have still required Studebaker to tool up for a completely new car line. Whether the Starliner and Starlight would have generated enough sales to be profitable under this scenario is the unanswered question.

In the end, it probably wouldn’t have made much difference, as Ford-GM sales war of 1953-54 crippled the independents, and badly damaged Chrysler.

We could wonder what if the Ford-GM sales came off a bit later (1955) or what if Brook Stevens had redesigned the Hawk a bit earlier?

Also, the old Studebaker sign at their former proving grounds is still there from what I read on Hemmings http://blog.hemmings.com/index.php/2012/01/05/preservation-effort-under-way-for-giant-studebaker-sign/

That was an article in an SDC Turning Wheels issue. I think the Model N was pretty nice looking, I’ve seen pictures of the finished prototypes in a Studebaker book. It was kind of a cross between a bullet nose ’51 Studebaker and a ’51 Kaiser. Here is a link to the ‘prototype graveyard’ article on Bob’s Studebaker Resource website:

http://www.studebaker-info.org/TW/tw0972/tw0972p08.html

Link doesn’t work.

try this one

http://www.studebaker-info.org/graveyards/studegraveyard/studegraveyard1b.jpg

Your comments did bring a lot of light. I am about to but a 1953 Stud Starlight and would like to learn more about the car. The car that I believe, still is one of the best car designs ever. It was never recognized but inspired many car designers.

Count me as one who really likes fender skirts in general but in this case they just don’t work for me and ruin the lines.

The preponderance of fender skirts on restored/show cars cracks me up. As the son of a car dealer back then, believe me that fender skirts were nowhere near as prevalent as modern owners of vintage cars attempt to portray. Unless they originally came with the car (rare enough that I can’t remember off the top of my head which manufacturers did that and when), fender skirts were far and few between.

Ditto for A-pillar spotlights, fake exhaust ports, fake dual rear antennas, etc. About the only bolt-on option that was common back then was the under dash tissue dispenser, as they only cost about five bucks and were really easy to install.

The AMT 3-in-1 car kits we grew up building had all that stuff. Grownups build these kits in 1-to-1 scale.

I built at least one of these back in the day, maybe two. I remember one as navy blue with a white roof. I always built mine stock.

as a lifelong car modeler, I`ve built the AMT `53 Stude twice. Once as a Bonneville salt flats racer with a chopped roof, and one stock in gray with a red interior.Ranks as one of AMT`s best kits, right up there with the `57 Chevy, `57 T bird, `49 Ford, and `49 Mercury in their original release incarnations.. Excellent model that still holds up today.

They build up really well, and stand comparison with the best of today’s kits. Here’s one of mine.

Yabbutt ;

We all _wanted_ to be able to afford those things Syke .

-Nate

One prototype ’53 Starliner convertible was built; the new ’54 grille and trim were retrofitted a year later. I think this prototype survived and is still around.

Studebaker did build one prototype Starliner convertible (see: https://www.curbsideclassic.com/blog/the-goddess-appears-on-two-continents-at-almost-the-same-time/ ), and apparently several others have been made into convertibles by third parties. Stude would eventually field a Lark convertible in 1960-64 which makes me wonder why they couldn’t do it back in 1953.

I AM 80 YEARS YOUNG. DURING MY TWENTIES I WAS FORTUNATE TO HAVE BEEN ASSOCIATED WITH TWO OF THESE CLASSICS. FIRST ONE WAS IN 1956. MY FRIEND HAD ONE AND WE WORKED TOGETHER A T BOEING AIRCRAFT IN WICHITA, KS. IT ENDED UP KILLING A HORSE ON A COUNTRY ROAD IN EASTERN KS. SECOND ONE BELONGED TO MY SUPERVISOR AT ROCKWELL INTERNATIONAL. HE GOT IT FROM SOMEONE IN INDIANA. I RE BULIT THE ENGINE AND SPRAYED ON 17 COATS OF BLACK LACQUER. THE FINISH LOOKED 3 INCHES THICK. WE ALSO DID A COMPLETE INTERIOR REFURBISH. MAY OF 1959 WE DROVE IT TO INDY FOR THE 500 TIME TRIALS. COULD HAVE SOLD IT FOR $7000.00 AT THAT TIME. HE KEPT IT AND IT BURNED UP 3 MONTHS LATER.

“I would love to see someone do a shorter version via photoshop.”

Here’s a quick and dirty ‘chop.

Original version for comparison.

Thanks. What would be interesting is to keep the same greenhouse, but move the rear wheels up some, thereby shortening the tail. The wheels so far out in back are graceful, but not in keeping with more modern coupe proportions.

Howsabout this?

That’s it! Don’t you think that looks better?

There’s an ideal for the placement of the rear wheel, which seems to be under the visual termination of the c-pillar into the body. With the longer wheelbase used on the original car, that isn’t going to happen.

The weird thing is, I’m so used to seeing the car the way it was produced, I really hadn’t noticed that the rear wheel was too far back. The 1971-1974 AMC Javelin had a similar issue, but not as pronounced.

Perfect! The stock rear end never looked overlong to me before, now it does. Nice!

It’s interesting how standard proportions regarding rear-wheel placement have changed since the ’50 and ’60s. Recall that sedans of the era (including Studebaker’s) often had rear doors that were completely, or almost, rectangular with no intrusion from the rear wheelwells. Nowadays that’s almost unheard of – the rear wheels almost always cut into the rear doors and the back seat is placed as far back as possible, often with the wheelwells bulging into the rear seat making an effective bolster at each side.

Or a SSK version?

That’s too stubby.

Imagine that puppy with a SBC and 4 speed in it! Although, with a short wheelbase like that, it would be very hard to control on launch…

You’re right though, aesthetically, it’s not correct.

I think it would look best with a slightly longer wheelbase, but also with a more fastback type roof. but its not just the wheelbase and roof that are wrong. its lower in the rear than the front. it looks like a dog dragging its rear legs.

You’re right, Aaron, and that’s a great picture to illustrate your point.

But we’re talking about the fifties, and that was the ‘in’ thing at the time, to have the rear lower. This rake was incorporated into a lot of the customs guys were building back then. It makes the car look like it’s sending power to the rear and accelerating hard when it’s at a standstill, or like a speedboat on the water, with the nose up. You’ll notice the way the body line drops from the cowl back – this also contributes to the effect. It was rather a daring thing for an auto company to put into production – but then Stude had something of a reputation for daring coupe designs!

That stubbiness will go away if you move the front wheels further forward…in other words put more distance between the front edge of the door and the rear edge of the wheel well…and lengthen the hood in the process.

Nice quick photoshopping! I agree with Paul the rear wheels are too far back. Keeping the greenhouse is another way of saying the personal coupe always has a back seat, which is narrower than a sedan’s due to the wheel wells intruding.

It was built in the metal the photoshop I mean, MK7/8 Hillman Californian and the Audax Rapier,

Squint a little, and you see a Karmann-Ghia.

(Oops, Tronan beat me to it.)

Marcks’ concept sedan is a nice looking car, especially for 1953. One could view it as a precursor of the now trendy four-door coupe, albeit with better rear visibility.

The chopped coupe strongly resembles a Karmann Ghia; others may disagree, but I think it improves on the somewhat ungainly look of the real thing.

What a great find and a great article! My father’s second car was a 1953 Champion Starlight. He had sold his first car – a 1950 Champion – to my grandparents and bought the Champion. He loved that car, and racked up over 100,000 miles on it, which is no small feat in Pennsylvania, considering how much salt is put on the roads in winter.

Another problem with the 1953 line was the frame. Studebaker engineered a high degree of flex into the frame. The idea was to allow the frame to “flex” with bumps, and absorb them before the driver and passenger felt them. Unfortunately, it resulted in two problems.

One, Studebaker hadn’t completely perfected this idea, so the cars ended up feeling creaky and junky. There was also a fair amount of noise generated by the flexing frame, which reached the interior.

The bigger problem surfaced as production of the cars began. The frames were so flexible, that when the engines were mounted in the Starlight/Starliner, the frames were distorted to the point that the front fenders didn’t mate properly to the rest of the body! This was another big reason for the production delays.

I remember reading that Robert Bourke had “priced out” a Studebaker Commander Starliner using GM’s cost structure. He discovered that GM could have sold it for LESS than the cost of a Chevrolet Bel Air. Studebaker, meanwhile, was charging close to Buick prices and still didn’t make much, if any, money on it.

The “Dead End” sign on the first photo is such an appropriate detail for this fantastic article!

I love all the coupes based off of this chassis. Let me place my fedora to my heart and bow my head for Studebaker.

Hey! The fedora is mine – you wear a cowboy hat, remember?

Man, that’s one beautiful car wherever one lives.

This…was a car in search of a market.

There wasn’t a MARKET for specialized cars in this era. Yes, the Corvette got in, and held its own; but even it had a struggle for years.

Why? Because our standard of living hadn’t risen to where two-car families were the norm; nor were there transportation alternatives for people with pretty-but-pretty-useless small coupes.

Consider today. A young guy, or girl, can buy a Corvette or Miata on an entry-level professional’s income. And, if he or she has the need to move something, he/she can rent a van or wagon or Budget truck.

In the day, that wasn’t doable. Your car…was your ONLY wheels. A sedan was needed if you wanted to travel with your friends. And even if that didn’t happen much, you had to think about resale. The market for such cars was very small, and even smaller used – when people drew status from the age of their cars.

And the playboy demographic was captured with British sports cars, or the Corvette. Or, for a few, the Thunderbird.

This was suicide. History shows it was the beginning of the end. And perhaps the styling didn’t set well…I know it’s not my favorite, other posters’ comments notwithstanding.

Nicely thought out. One of the biggest errors we tend to make on this site is to look at just about every car from a 2011/2012 vantage point, completely forgetting that back then people didn’t think in the ways that we do now.

To further elaborate, a ‘young guy or girl’ back then invariably ended up with something 5-10 years old. There was no way they could afford something nice, new and sporty.

For that matter, the concept of the ‘teenager’ – the idea that youth was different in style, thought and way of life was only beginning to come around in 1953. Up to that point (and for a while afterwards, in diminishing amounts) the person in their late teens or early twenties were nothing more than slightly junior versions of their parents.

And, the ‘playboy’ demographic (back then) was not necessarily something to be proud of . . . . . . .

Very true. Also note that young women weren’t major purchasers of cars back then. In the early 1950s, the main goal of most young (meaning, late teens and early 20s) women wasn’t getting a job to buy a spiffy new set of wheels. It was finding a husband and getting married.

Many women who went to college did so to find a better class of husband (as my wife’s grandmother put it, they were pursuing “the MRS degree”). I’m amazed at how many of my older female relatives who did pursue education after high school in the late 1940s and 1950s either dropped out after getting married (to a fellow classmate, who DID graduate with a degree), or graduated, immediately got married, and had children right away.

They weren’t looking at Studebaker Commander Starliners; they were looking at Ford Ranch Wagons or Country Squires.

There were definitely plenty of women in the ’50s who went to college because they wanted careers as something other than secretaries, but the overwhelming culture of the time treated them like outcasts, and ignored by the mainstream media (at a time when there wasn’t much non-mainstream media). It was just starting to change, but it would be about two decades before it was widely viewed as mainstream.

As was the generation before them who had fought WW2 and as often as not immediately paired off and started families.

25 years later, when they became empty nesters and their children young professionals who were outgrowing their aging VW Beetles and muscle cars …THAT was the golden age of personal luxury.

And Studebaker didn’t have a station wagon.

The “youth market” as seen in 1955’s “Rebel Without a Cause”.

In line with your comment is the fact that Studebaker sold a disproportionate number of its cars in California back then. As now, the state was very fashion-forward, and postwar Studes (going back to the ’47 Starlight Coupe) were well received there. The salt-free climate probably did not hurt, either.

Studebaker had an L.A. Assembly facility and it was only reluctantly shut down around late ’55 when S-P as a whole, was really starting to go “up against it.”

Paul Hoffman, CEO was himself Los Angeles based and had not only California’s largest Studebaker dealer, but was himself a distributor.

Photographs of my parents dating in 1952-53 in San Francisco show lots of Studes on the streets (Mom had a ’47 HydraMatic Olds 76 back then).

I wonder if Studebaker were popular in San Francisco because of the hill-holder option.

When the standard of living in America started to rise in the mid-fifties, it was Ford who tried to captilize on this trend encouraging people to become “a two-Ford family” beginning in ’56.

I love that dead end sign…what a fitting metaphor! The Starliner was a beautiful automobile but Studebaker simply could not afford to build two seperate lines of automobiles. Studebaker had set up a production schedule of 350,000 units to be split 80% sedans, 20% coupes. When the Starliner was shown in October of 1952 they were quickly accepted by the public, but management at Studebaker had not scheduled any production of the coupes until 1953, and production was running 80% coupes, 20% sedans; just the opposite of what had been planned.

Ironically when Studebaker started production of the Avanti ten years later, it was haunted by many of the same production problems. Molded Fiberglas Company was supposed to supply complete trimmed bodies, but the pieces wouldn’t fit and Molded Fiberglas’s facilities were largely taken with Corvette work. Studebaker had to put in its own plant-delays mounted and many buyers who had lined up to purchase one went elsewhere.

When the halo car of most companies’ car lines in the early 1950’s was the new 2-door hardtop, Studebaker’s was still the long-wheelbase 4-door Land Cruiser sedan whose vent windows in the rear doors were the most noticeable difference from the ordinary sedans. They paid more attention to that car in their advertising than the unique Starlight coupe, and finally in 1952 there was a 2-door hardtop to sell besides the coupe.

In 1962 or so I found a 1953 Commander hardtop on the back row of a small used car lot in Tacoma. It was painted in 1956 Chevrolet beige and red-orange and was decent looking inside and out. The reason for its back-row status was that the engine was in pieces in the trunk. Well, a guy who worked for my father had a 1951 Land Cruiser that he was planning to sell, so I picked that up pretty cheap. Using a hydraulic backhoe for an engine hoist (the best ever, as you can wiggle the load from side to side as well as up and down), the 1951 engine and tranny got transferred into the 1953 car. The only difference between the two installations was that the shift linkage needed to be modified slightly. Everything else bolted up, even the wiring harnesses were the same, and I had the car driving in no time at all. But I was going to college at the time, money was tight, and the ’53 needed some exhaust work and other minor stuff, so I sold it. I probably didn’t put more than a couple of hundred miles on it.

One thing I like about the styling of those cars is that from most angles in the rear, you can see the reflection of the taillight on the trunk lid next to it. And one thing that I noticed about driving it was that if the car was light colored as mine was, light from the headlights would be refracted upward from the surface of the body in front of the light – not strongly, but enough to be noticeable.

I ended up with an extra set of those cool-looking wheel covers, that I used on half a dozen other cars in the subsequent years, none of them a Studebaker.

I walked by this exact car last summer and thought of CC immediately, of course. Had my camera one me but the sun was nearly down and I couldn’t have done her justice. I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised. Paul gets around. 🙂

I drive by it when I take the long way home, it’s been there off and on for years. Happened to mention it to Paul (before I started writing here) and he got these outstanding photos when he came up for the art museum car exhibit. Funny, I always go by this car downhill, never noticed the “Dead End” sign which faces the other way. Paul sees these things.

…First Star I See Tonight.

Fabulous story Paul, nicely done. Bob Marcks’ sedan is gorgeous. If only…

“Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.” Soren Kierkegaard (1813 – 1855)

The ’53 Starlight Coupe is my all-time favorite old car, I’m just crazy about these cars. It’s always a thrill to see one. But bittersweet, its story is so sad. By ’55 it was ruined.

I once stumbled into a ’53 coupe in modern custom form: completely dechromed, nicely styled bodywork where the bumpers used to be, slightly lowered, fabulous paint. It looked totally modern. Stunning. Wish I could find a photo. It might have been the one shown here, but the one I remember is even sleeker.

Here’s a more elaborate custom ’53 that’s true to the original:

http://www.popularhotrodding.com/features/1106phr_1953_studebaker_coupe/viewall.html

Its shape was so perfect.

Carnut has a big page chock full of ’53 Studes, custom and stock:

http://www.carnut.com/photo/list/stude/stude53.html

Marcks’ idea of a four-door version is interesting, but I suspect that it would have flopped. The lack of a step-down chassis meant that the Starliner body was terribly cramped, both in the rear seat and the trunk. The 1951 Kaiser — which may have been a partial inspiration for the Starliner — partially solved the rear-seat-room problem by raising the roofline, but that destroyed the car’s low-slung looks. On the other hand, imagine if Hudson had decided to invest in an updated and much-lower Hornet body instead of the Jet.

It sounds boring, but if Studebaker had any hope it would have been to ditch the Starliner proposal in favor of an updated and unit-body Champion, which had always been a solid seller. AMC effectively stole the mid-sized sedan market with the 1956 Rambler, which was the backbone of AMC’s remarkable success through the early-60s.

A halo car could have worked in the 1950s. That’s essentially what the original Nash Rambler was — and it sold reasonably well. The problem is if the car’s success hinges largely on fresh styling. There’s no way that an independent automaker could have kept pace with the Big Three’s rapid restylings.

That’s one reason why the Rambler aged better from a sales standpoint than the Starliner. Over time Nash moved the Rambler more toward a utility-oriented and low-cost compact.

> There’s no way that an independent automaker could have kept pace with the Big Three’s rapid restylings.

The amazing thing is that they almost did. Even though Studebaker was stuck with the same basic body from 1953 to 1966, almost every year’s car got a thorough makeover. If you look at a ’53 sedan, a ’58 President Classic, a ’60 Lark, and a ’64 Cruiser, it’s hard to tell they’re so closely related. The coupes didn’t get as many facelifts, but the stunning ’62 restyling (courtesy of Brooks Stevens) was a stunner that looked almost completely up to date despite retaining almost everything from previous years except the roof and rear windows.

The 1962 Hawk update with the Thunderbird style C-pillar was absolutely stunning to behold. The wide C-pillar nicely balanced the old problem of the roofline being too far forward (or the rear wheels being too far back). It has perfect proportions and was a worthy competitor to anything else on the market at the time. Unfortunately, it also suffered from the same willowy frame and quality issues. Sadly, Stude just never managed to get it all together.

“Perfect proportions” is a phrase I often use describing the ’62-’64 too. Look at a ’53 Chevy or Ford and try to imagine a facelifted version of those (with the same fenders, doors, and windshield as the ’53) looking at all sellable in the ’60s.

Another brilliant aspect of the ’62 facelift is that it cost less to make, without the bolt-on fins or highly curved rear window.

Because of the old straight frame they had half a foot well on each side of the back seat floor. Other mistakes were the too-flat windshield too far back with too high a lip at the bottom, resulting in a shallow dashboard and a too-high windshield as seen from inside. Then they put the instruments down low to make it worse. The ventilation system using a remote opening door in each front fender must have cost more than what everyone else was doing, besides putting that rectangle in the fender. On four door sedans, they still had a spacer between the doors when everyone else had them meet. A lot of body engineering oddities that detracted from the cars and cost more.

I was going to make a post about the wierd lopsided footwell. I’ve never been inside one of these, but I peered through the windows of a ’55 Speedster and saw that floor and thought “this can’t be right”. There’s room for only one foot! Was this design maintained all the way through ’64? Did the sedans (or the Avanti) ever use this design?

The flat, tall windshield does give it an evocative classic look from the outside that evokes 1930s cars for me, but it clearly would have been better to use something more modern.

Another annoyance of the coupe body was the low, narrow trunk lid that effectively cut off the left and right sides of the trunk. Even though the ’56 and later models had a new taller squared-off trunklid, the underside from the earlier trunklid was retained to save money so the newer cars still didn’t have any more trunk space.

The spacers between the front and rear doors were still fairly common in ’53 but not much longer. Studebaker finally got rid of them on the 1963 models which had a revamped greenhouse with larger windows, a modern non-fishbowl windshield, and a new dash.

My first thought: Amazing that the same company took the risk to build both this car and the Avanti.

My second thought: Only this company had to take the risk to build both this car and the Avanti.

Just as the ’53 Starliner was the unheralded first personal-luxury coupe, the Avanti was the unheralded first pony car. It was a low-slung, sporty coupe built on the platform of the company’s compact car, in this case the Lark. Nearly two years later, another company would do the same thing with *their* compact car, the Falcon….

I remain unclear why the Mustang was such a hit and the Avanti was such a bomb, at least commercially. Obviously their manufacturer’s relative financial positions had alot to do with it, and to my eyes the Mustang is better looking, but conceptially they’re awfully similar.

Perhaps because the Avanti cost twice as much as a Mustang?

Did that hold true if you equipped them similarly?

It was overpriced for sure, marketed as a Corvette competitor instead of, well, the Mustang didn’t exist yet.

Of the ten or so ’63-’64 Studes factory-equipped with the supercharged, overbored R3 304.5 V8, most were placed in Avantis, but one Lark pillared coupe – the lightest and least-expensive body style – was ordered with an R3 and a 4-speed stick. Someone was in early on the muscle-car ethos.

No, but the gap would still be huge. In 1963-1964, that meant something. The Avanti was not affordable for the average buyer; it was a premium sport-luxo-coupe. In my opinion, it was not a direct Corvette competitor, but more like a sportier Riviera.

The real issue is that even if a lot more folks had wanted an Avanti, Studebaker could never have built them in any volume anyway. They had a hard enough time building the small numbers they did, with the fiberglass body and all. It was not even intended to be a volume car, just a classic “halo car” to help Studebaker’s image.

I love Studebakers, if not for anything, but their underdog status. It is sad that the inept corporate leadership, accounting and then renegade South Bend UAW dragged down Packard after the S-P merge (nobody bothered to look at the South Bend books BEFORE the merge!).

I don’t know if I would call the South Bend local a “renegade” unit. Supposedly management simply gave it whatever it wanted. Studebaker management prided itself on operating America’s “Friendliest Factory.”

Given that almost everyone – management and labor – working at Studebaker in the early 1950s was either an adult or a teenager during the bitter sitdown strikes at GM and the bloody “Battle of the Overpass” at Ford, that wasn’t necessarily a meaningless boast.

I remember a quote from a union official who later said he couldn’t believe that Studebaker management give in so easily to union demands.

When the union official thinks management should have said, “No,” that should tell you something!

Another version of a shortened Studebaker coupe…

http://www.sunbeam.org.au/models/rapier3.jpg

One of my Minxes sporting relatives

The ’53-’54 Studebaker Starliner is ‘the’ car that one of the domestics needs to produce in a modern, retro version. It’s such a beautiful, timeless, classic design and it would be great to see one without all of the issues that the original and could be used as safe, reliable, daily transportation.

Gosh that’s an interesting idea. It’s not too hard to see a modern Starliner in some of the better customs.

When did Toyota start importing its Land Cruisers into the US? (fairly early in its US history, IIRC) Was Studebaker already too weak by then to contest the trademark?

Hard to say when Toyota started using the “Land Cruiser” name. I am sure after Studebaker’s use of that name, certainly after ’52. In ’54-’56, DeSoto two door hardtops were “Sevilles” to denote the city that Hernando DeSoto started his new world expeditions from; Cadillac began using “Seville” to denote the hardtop version of the Eldorado in ’55 through, I believe ’58. Not sure if Chrysler protested of GM’s use of the Seville name or not.

What about the Studebaker Starliner and the Ford Starliner?

Drool(:D

I had always thought that the Starliner coupe resembled the 2nd generation Camaro. Especially the 75 and up with the wrap around rear window. I’d like to see what the Studebaker would look like with rear side window removed.

You could find out by rolling down the hardtop’s side windows – this was the era when coupe rear windows were still expected to roll down.

Except for the rear pillar and glass, the two cars don’t look much alike to my eyes.

I own a ’54 Starlight coupe and it is one hot looking car.I live in Ontario,Canada and in almost all car shows I participate in,my Stude takes a prize.People rave about the styling and many have said it looks better than current cars and say it should be made again,long live Studebaker!

> it should be made again,long live Studebaker!

As a fellow Studebaker enthusiast, be careful what you wish for! Some things are better left in the past, or else we have this:

http://www.studebakermotorcompany.com

Could you put a photo of it up?

As the owner of a ’54 Starliner when I was very young in the late 1950s, I read your page with great interest. Attached is/was my car with a descriptive caption. Please use the photo as you see fit.

Don Struke (in Baltimore)

No one has mentioned where all of these cars went! They have been shipped to Mexico, Australia and New Zealand and are used as race cars. Utube has several videos of them in all kinds of race conditions. I own a 54 post coupe I bought from one of the folks who run the Pan Americana in Mexico. He felt it was too nice to be raced. I agree! They are getting harder to find everyday. I would buy a 54 HT because I want to make a convertible. Are there any out there? Please email me if you have one.

We own a ’53 that was customized by my wife’s father and uncle 60 years ago in Custer, SD.

Restoration was completed in 2011. Pictures at jimsrodshop.net (project # 31).

I bought a ’53 Starlinder Regal hardtop from it’s original owner in 1978, creme with a dark “air force” blue top, red interior, wide white wall tires.

This car literally took my breath away. I’d bring a kitchen chair into the garage, sip my coffee (or whatever) and just stare at it’s Beautiful Body. It looked perfect from any/all angles. How many cars can this be said about? The wrap aroud back window appeared on the ’75 Camaro, as did the long, sloping hood.

It made my best friend’s 1956 Chevy Bel AIr look like the shipping crate my Studie was shipped in!

Hi, all. Need help identifying this car. Any idea what year???

1955 Commander Regal Hardtop Coupe

My first car was a ’54 Commander Starlight Coupe, red/grey interior, & wide whites:

and I got it in ’57 when I was only 16! Also, with Mom & Dad, picked up a new ’51

Commander Starlight coupe (full wrap-around rear window) at the South Bend, IN

factory the popular (and ugly/drab) light “Sea Foam” green. In ’51 it was like a

rocket ship! Had a factory-installed propeller mounted on the bullet nose, which

I’d never seen before or since. I couldn’t believe it: Dad said it made it go faster,

just like an airplane. That made sense to me. It chopped-up billions of summer

bugs from Indiana to So. Cal. (and it was really cookin’ in the backseat surround-

ed by glass and no roll-down windows!). Where have they all gone? Don’t even

see any at local ’57 Chevy car shows (they were ugly in ’57 and still are today and

so were ’57 Studebakers). Lu.

Another one the belt and suspenders guys at South Bend muffed up,but is there anyone who can`t say that this was the first “personal luxury coupe”. Beautiful from any view, but loose those hideous fender skirts!

This is one of my all time favorite cars. So beautiful and ahead of its time stylistically. It made every other coupe sold in ’53 look ten years old.

Two things bother me though – that chrome V8 badge stuck on the rear fender where no badge should ever be, and the strangely exposed (from the interior) hardware holding the windshield in place. Why didn’t they make the top of the dash two inches higher to cover that?

I too can’t fathom why Studebaker didn’t save themselves lots of money and improve the styling by making a four-door version of these instead of a separate car that looked like it shared its body but didn’t. Bob’s model looks better than the real car did, though I would have placed the B-pillar slightly forward to balance the front and rear doors better. (OTOH, the wider front door would come in handy a few years later if they wanted to change to a wraparound fishbowl windshield – something they did to the sedans but not the coupes).

The V8 emblems on the quarter panels were put there because of the V8 emblem that had been schmucked up on the hood’s nose. Just the usual Studebaker stupidity.

It just breaks my heart every time I see a ’53 Loewy coupe. Such a beautiful, timeless shape. It could have been a game-changer, but never had a chance thanks to incompetent Studebaker management.

The V8 badge on the rear fender is one of my favorite styling elements of these cars. But they really tacked on more and more junk with each year. The optional reverse lights were the worst.

The gages on these remind me of an old woman’s boobs. They’re much lower than you’d expect.

dropped by 1955 for high-mounted round gauges, reshaped to aim toward driver from ’62 but same dash beneith new padding.

In 1978 I was the proud owner of a ’53 Champion Starliner Regal hardtop, crème/white body with a darker “Air Force Blue” top, the very same red pleated interior as in this article’s car.

My best friend at the time had a ’56 Chebby Bel-Air that he was also very proud of.

We’d often cruise New Orleans’ Lakeshore Drive, park along the seawall and wax our cars.

His Chebby looked like the shipping crate my Studie came in!

EVERYBODY knew what make his car was; very few people knew what a Studebaker was. It irked him to no end that my old car got much more attention than his did!

Please, throw those skirts away!

Just a gorgeous car, and one in an endless line of examples that beauty alone cannot solve all your problems.

One line from the article struck me though: “But then drivers have always fallen for the allure of something more stylish and expressive than a dull sedan. ”

Not anymore. Now it’s all dull sedans and personality-free people carriers. Maybe SUVs are capable of being more expressive in what they suggest about the driver, but they’re certainly not more stylish. The coupe is dead and buried, and I don’t think we’ll ever see it rise.

I disagree with that idea of shortening the coupe. I think that the car in real life really needs that longer taper to get across its grandeur. (and there really wouldn’t have been any trunk space without that longer rear deck, given its low taper!)

Here’s a case in point — a ’54 Coupe that got shortened in the process of making it a convertible — it’s on Craigslist in Virginia right now. This car looks wrong on every level to me (maybe it’s just a bad job…):

http://washingtondc.craigslist.org/nva/cto/5161102447.html

This month’s SDC Turning Wheels magazine has a nice story about the one and only ’53/’54 factory prototype convertible ever made. It, conversely, looks pretty ‘right’ (except for the extra Chrome added in ’54)…. wish I had a scan of some of the pictures showing it.

Ed Reynolds, of Studebaker International [South Bend and Indianapolis] has the 1953 Starliner convertible prototype. Several one-off convertibles have been done, some with X-member center sections, even the Lark convertible seven years hence, did it this way. Even modest reinforcing of the frame rails would make it acceptable.

It’s amazing that I just happen to have a 69 Grand Prix and a 54 Studebaker Coupe in my garage just now. I did not think of the similarities until reading the above comment. John D was awesome, as was Bob Bourke working for Raymond Loewy.

The Stude is in rat rod form now, with 6 deuce carbs coming out of the hood, while the Grand Prix is mostly stock with just being lowered and mild engine mods.

Both great cars.

European styling indeed. The first car I remember in my family was a 53 Studebaker coupe. My father took it with us when we moved to England for 2 years in the late 50’s. I remember riding in it (with Mum , Dad and 4 brothers and sisters – must have been a big back seat) on those narrow English roads and Dad would say to whoever was in the right front seat “Anybody coming?” before passing the car in front which was always inevitably slower than the V-8 coupe. We always made it. He was a good driver.

It must have been quite a sight for the locals. My memory of English cars of the time was that they all looked like they were built in the 30’s.

The 1953-54 Commander Starliner is my all time favorite car; it’s what got me into Studebakers. Sadly I only had one (an early 1953 in grey with a burgundy top) in my possession for a brief period of time before life threw a curveball and I had to part with it.

Those fender skirts on this one are a no-go for me, though.

If something like that Bob Marcks proposal had been built, Studebaker would have been in on the “four door coupe” trend about 60 years early. But as good as it looks, I don’t think it would have sold well due to insufficient interior space. The 1953 Stude platform, a body-on-frame design that couldn’t accommodate recessed footwells, already compromised the actual 1953-66 sedans they built. Having to share the coupe’s low roofline would have made things even worse. Keep in mind sedan buyers in 1953 were used to the much taller bodies that typified Detroit’s offerings of that time, as well as Studebaker’s own 1947-52 models.

My first car was a 55 Studebaker coupe hardtop. The coupes were popular in high school. My friends had a 53 and a 54 coupe. My 55 with a floor stick was much faster than their cars and was faster than most cars on the road even in 1961. The 55 had a four barrel cab and may have been modified. It was originally an automatic and had highway gears. It had candy apple red paint with Frenched headlights and 56 Packard taillights. It was so beautiful that I would spend hours just looking at it.

Thought I would post the only photo I have of my 53 Stude (right), my sisters 54 is at the left. My brother had a 54 hardtop at the time, and my mom had a 53 sedan.

Paul Hoffman was a friend of the family. Photo c. 1959.