The robbers had somehow entered the house. How did dad and mom never heard them is beyond me, but it was now up to me to find a way to save our home; a daunting task for a 6 year old. Fear not dear readers, the menace was easily sorted out. After all, such is the world of childhood dreams. The specifics elude me, but the robbers were certainly sorry to have crossed paths with me by the time I woke up.

A bit of a hero complex? Maybe. But such is a child’s mind; incredible goals achieved with the easiest of efforts, to end up savior of the day, admired by all. Any other childhood dreams? To build the first car in our nation! I loved cars more than anybody; who else better to build El Salvador’s first car?

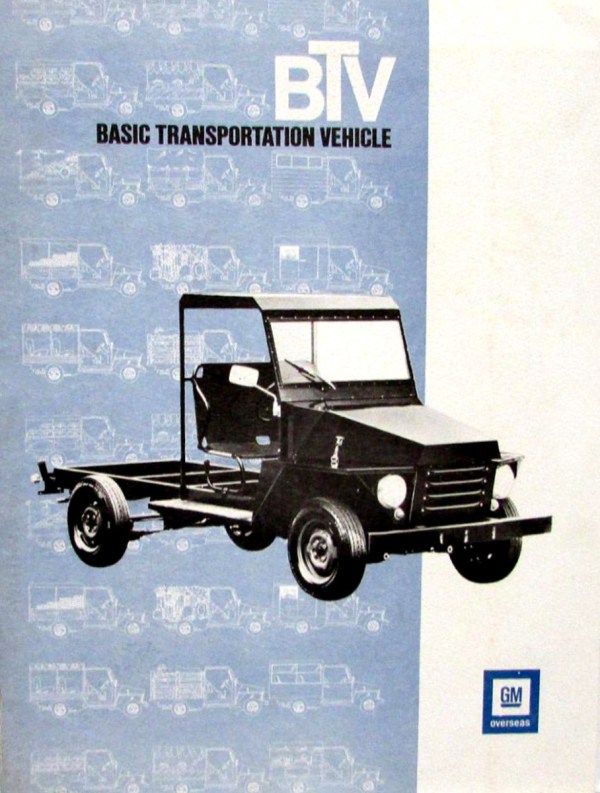

Unbeknownst to me GM was already selling such dreams in Central America; it was the BTV project, a somewhat askew effort to get developing nations into car production. “El Cherito” (Little Pal) was El Salvador’s version, the nation’s first and only car to date. Starting in 1973 the fruits of the scheme became available to any adventurous Salvadorian with nationalistic tendencies and -more importantly- a shoestring budget.

What we’ve here is a rare breed, possibly the only running one in El Salvador. Not many more still in functioning form in Central America either. Yet, CC’s contributor pool is so wide the BTV project has already appeared some time ago. Further information on the little car’s obscure saga has emerged since then, mostly in local newspaper articles. With that in mind, let’s delve once more into the matter; just beware local journalism is not known for being too rigorous. While scrutiny has been done, sorting out fact from fable proves difficult against the scant information available.

A Spanish site claims the B.T.V. (Basic Transportation Vehicle) project was first shown during a 1969 meeting at Vauxhall’s headquarters. Meanwhile, Wiki states it was an effort from General Motors Overseas Operations (GMOO). Regardless of when and who, Vauxhall was involved, as the proposed easy-to-assemble vehicle would carry Vauxhall engines and components. Apparently Vauxhall’s management didn’t take too keenly on the plan, though the prospect of attending overproduction matters through the scheme ultimately won them over.

Most of the BTV’s Vauxhall genes would come from the Bedford HA Van, itself a derivative of the Viva. The Spanish site credits Opel with additional design work on the BTV’s chassis, simplifying what they had already done on the Viva/Kadett. The final specs were aimed towards a simple utilitarian pick-up type, with a loading capacity of 600 kilos.

Information varies on engine details. In El Salvador’s case, it was a 1256cc Bedford with 59HP. In other nations power seemed to have ranged from 37 to 59HP. A Nicaragua site mentions Milford mills (the only to do so). Most of the electrics came from Vauxhall and Opel.

With the project greenlighted, nations with no background on car production were approached in Asia and Latin America: Malaysia (Above), Philippines, Paraguay, Ecuador, Suriname and most of Central America. One European nation made the roster: Portugal.

Bodywork would be handled by each plant, depending on local expertise and materials. All participants having limited industrial capabilities, the recommended ‘styling’ consisted only of flat panels. Arranged in the simplest of manners, each version met the lowest threshold of ‘bodywork.’

Plan in motion, GMOO’s salesforce got quickly into action, having some kind of itch to get rid of Bedford engines. Available literature offers typical American so-easy-anyone-can-do-it selling points: “All it takes to start a BTV plant is a structure about the size of a large barn, $50,000, and the national will to begin industrializing.” Of course GM would do the hard part: to sell provide engines and drive trains scattered around Vauxhall’s warehouses.

By the early ’70s enough dreamers had been found to start assembly in the aforementioned nations. Most versions got rather friendly names: “Compadre” in Honduras, “Chato” in Guatemala, “Pinolero” in Nicaragua, “Amigo” in Costa Rica, Portugal and the Philippines. In Ecuador the “Andino” (from the Andes) name was used, and “Mitaí” (a Quechua word supposedly) in Paraguay.

Assembly in El Salvador lasted from 1973 to 1975, at Fabrica Superior. The Frenkels were the local investors, a wealthy family traditionally involved in car matters, owners of the Superior battery plant and longtime dealers of Chrysler products. By the ’70s that meant mostly rebadged Mitsubishis and thus, both Dodge’s Lancer and El Cherito found a selling spot at ‘Auto – Palace,’ a luxurious art deco structure belonging to the Frenkels (Toyota was next door, selling Corollas and Publicas).

In a local newspaper interview, an El Cherito ex-assembler told of the car’s production woes at Fabrica Superior. In his recollection, before their arrival to El Salvador, some Bedford engines had been poorly stored and tended to seize/fail after a few months of use. Also, as simple as Opel’s chassis specs were, it was still more than could be locally handled. Fabrica Superior’s personnel made further changes, and El Cherito ended up with a tendency to turn on its side during quick turns.

The plant had about 20 employees, and unsurprisingly, most had issues with the car’s looks. Some dared to make suggestions, only to be nulled by management (probably a good idea). Between looks and questionable assembly, the car found a cool reception in the market. In all, around 800 El Cheritos were put together in different degrees of fit and finish.

Not that any such disappointments matter to this El Cherito’s owner. Restored and converted to a coffee-truck, the enthusiastic entrepreneur has turned his café gourmet enterprise into a branding exercise merged with the car’s history.

While El Cherito fizzled in the market, there’s a certain mystique that lingers in the public’s mind regarding the whole matter. So rare its failings remain unknown, the venture awakens the imagination when mentioned: “You know, there was a car built in El Salvador…” As the sentence hangs in the air, the usual reply follows: “Really…?” Always with a glint of excitement in the eye, curiosity piqued.

To this mystique has ‘El Cherito Coffee’ tied its branding to, and the car has become a staple in local festivities and street fairs. In previous posts I’ve told of the tribulations faced by local coffee producers; once a tent pole for the nation’s economy, they now face great odds against massive competitors such as Colombia and Brazil. A focus on specialty breeds has flourished in an attempt to eke out niche markets.

I’ll admit this was no casual find, nor was it a hunt. Instead it was a ‘wait,’ as the owner has a rather active Instagram account. With constant updates on the coffee-truck’s whereabouts, it was a matter of time for El Cherito to come close to me.

While I had an easy time tracking this El Cherito, it was an entirely different matter for its owner. From junkyards to classifieds to word of mouth queries, it took him a few years to locate one. When finally found, the little truck went through a full overhaul, well covered in his Instagram account (For those with memory, the previous guise of this El Cherito appears at the end of CC’s original BTV post).

The Vauxhall engine is long gone. In its place a 1,300cc Nissan is found. Considering its BMC origins, that’s as close to British as possible under current circumstances, and quite keeping in spirit.

A lot of liberties were taken to refurbish this El Cherito; common hardware door knobs, handmade aluminum siding on the window frames, etc. In reality, not much different to the car’s original assembly process.

Talking about which, what went wrong with the BTV project? Besides GM’s dubious involvement, the venture suffered of production issues rooted in Central America’s non-industrial historical conditions (I won’t elaborate on Malaysia or South America).

To start, raw materials for industry are non-existent in the region: be it iron, aluminum, or rubber, all are imported in processed form. Lacking such resources, economies of scale became nearly impossible. Utilities -if any- were minimal.

A complex political background didn’t help either. By the mid-20th century wealthy landowners mostly wished to stick to agricultural goods, with a vocal minority pressing for industrialization. Military governments tended to favor the former, in a complicated relationship.

The ‘industrious’ minority offered mostly basic goods such as shoes, candles, fabrics and processed foods. Thus, ‘specialized’ bits for car assembly such as hinges, lightbulbs and hoses were imported, and not always readily available. For Fabrica Superior this meant improvisation was the norm in order to deliver ‘finished’ units. This may explain El Cherito Coffee’s Jeep front, as it was not the model’s usual face.

While the upper classes dithered around in the political arena, the region erupted in civil wars by the late ’70s (The Frenkels left for the US in 1980, the old ‘Auto – Palace’ building now occupied by small auto parts stores). What little there was of the BTV project by then, it came to a definitive end.

Finally, there’s the matter of timing. The BTV project arrived a good 10-15 years too late to a market already flooded with accessible Japanese cars and cheap trikes (the latter a favorite with delivery men). While costing a bit more, those wishing for a vehicle preferred to invest in a better known quantity.

Regardless of the project’s fate, in these non-industrial nations the myth of the ‘nationally built car’ endures, and the few surviving samples are most often seen in private displays and museums. Production numbers and dates vary widely from country to country, with Wikipedia sources placing total BTV units at no more than 3,000. If so, the 800 figure mentioned for El Salvador is probably wishful thinking or bogus accounting.

My wife, our household’s coffee expert, declared El Cherito’s Coffee as excellent. There are no childlike dreams behind El Cherito’s current owner aspirations, instead they’re adult ones, full of hard work and persistence. Intended or not, his coffee-truck enterprise seems to embody the conflicting visions of our nation’s past. Dreams that failed at the time, for that is the cost of dreams; aspirations meet harship, setbacks, and -more often than not- failure. The road to prosperity is a crooked one, and dreams make the only known map towards them.

More on the BTV:

Automotive History: Compadre – The Anti Cadillac For Developing Nations

It’s quite interesting and actually, on the surface, not much less refined than the various “step-vans” used for decades and still used here, mostly for local delivery type of jobs as well as of course food trucks.

There’s also a hint of Cybertruck. 🙂

This is my kind of truck! Simple, easy to fix, and its looks are irrelevant.

Thanks for shedding more light on the BTV; it’s pretty obvious why they didn’t catch on: harder to build than anticipated, and buyers wanted something that had more prestige value. Pure functionality has never been an asset in a consumer good; at least for most people.

I have had day dreams of a modern day BTV, in EV format that could be built locally in small to modest numbers. But it’s just that…it would never fly.

Interesting, the same thing was done in New Zealand but using Skoda Octavia mechanicals to produce a small pickup, they sold mostly on the very cheap price and you could just march in with cash and drive away rather than joining a queue to wait untill your particular car was assembled.

Trekkas were not that great or really that bad, they were cheap moderately durable fairly ugly and didnt do well when the Japanese opposition showed up in force in the 70s I havent seen a live Trekka in quite some time. live Japanese pickups from that era are also extinct they looked good but were fragile.

Superior, with that stylised S-in-a-box logo, down there at the bottom of the Auto-Palace SA ad (second image in this post), and then again as the full SC-in-a-box on the blue Cherito’s data plate: H’mm, that’ll be Superior Coach, of Carrollton Bus Disaster infamy.

Looks like Fábrica Superior just took Superior Coach’s logo and repurposed it. Not a rare occurrence back then, a few local businesses just ‘took’ logos and designs from abroad. In those pre-internet days, who would’ve known?

If my memory is correct, Superior built bodies on bus & truck chassis, while Superior Coach built bodies on GM passenger car chassis, mostly Pontiac and Oldsmobile. Later both companies were combined under the Superior Coach brand.

In the 1980s and early 1990s I spent time setting up a $10 million rental vacation villa in Barbados for a wealthy client, and when we needed various mechanical and electrical items, we first tried to source them from other “CariCom” [Caribbean Community] countries, or pay import fees of up to 162% if the item came from outside the CariCom.

I became familiar with how various businesses in Caribbean and Central American countries operated in offering various equipment, vehicles, and small parts. If I needed something I would go to the company who had the contract to sell that item. I would pay for the item, and it would be shipped in from either another CariCom country, or from the USA/Europe.

These companies often had no local inventory available due to the high import costs, but they did have the product signs and advertising. When we needed a new Mitsubishi pickup truck, we visited the truck dealer and ordered it from a book listing the vehicles available from the USA. It’s price was about 3 times the cost in the USA. None of the car dealerships had any new cars in stock on the island. Cars were shipped in by boat or cargo plane once purchased.

I suspect the Auto-Palace had an arrangement with both Superior and GM to bring in a rolling bus chassis along with the body parts, to rivet body panels together to make a Superior bus, if one was ordered. I suspect the Superior Coach VIN plate was made in the CariCom and used on various vehicles that were assembled in El Salvador. I also noted the ID plate was for [rough translation] “Factory Superior of Central America”, not just for El Salvador.

For small-time operations like this, while they had the agreement to assemble Superior products, they may have only assembled a few of these little truckettes and used the Superior ID plate, while never even assembling 1 actual USA- designed bus.

While in Barbados, the Villa’s owner found a Morgan +4 that had been assembled from a kit, and while it had a set of permanent Barbados license plates, the car had no VIN. Never had one. The Morgan was identified by the license plates only, and It was the only Morgan in the country. In order to bring it to the USA. I ended up asking Charles Morgan at the factory to “find” a chassis plate that happened to have the same VIN as listed on the Barbados license plates. Since it had never had a chassis number issued, that was permitted under UK law.

Fascinating history – thanks for digging into this, and it’s amazing that one of these is still running. I recall reading the earlier CC article about the BTV, and I’m glad to read some more detail.

Even accounting for the logistical and economic challenges in all of the participating countries, I’m surprised that none of the BTV vehicles was in any way successful. I’d have guessed that at least one or two might have been able to find a niche in its native country. The Malaysian Harimau (Malay for “Tiger”) would probably be my choice for Most Likely to Succeed – I think it was the most basic, with no doors, and no rear bodywork (assuming that purchasers would just make their own). But if the Wiki estimate of 3,000 worldwide production is even close to reality, I suppose all the BTVs met a similar fate to the Cherito.

Oh, and that Frenkel Auto Palace building is a great art deco design!

According to Wiki, there was actually one BTV offspring in The Philippines; a more car-like 4 door version known as the GM Harabas. No mention as to how many of those were built, but seem to have more survivors than any other BTV.

Great article, and an appropriate use for the oldest type of light truck, a screen-side espresso.

There’s a world of difference between having a local automotive industry and actually buying its product. I’m Australian, but I never owned a Holden. We can like the idea, the theory, the concept, and get all patriotic about it, but when your money is hard-earned (as you’ve told us before) to a degree the BTV plan’s originators could never imagine, purchasing their product is another matter entirely. If you’re going to spend such a large proportion of what little you have, you want the truck to be good.

With no local component industry and all the bits having to be imported, with all of the resulting supply and tax/duty/tariff/mordida issues, what could possibly go wrong? 🙂 That’s before we even look at the product itself.

A good idea in theory, but from what you tell us, maybe it should have been left as that.

What an interesting vehicle and story. Thank you for sharing. One has to wonder if some sort of fabric or leather body might be have slightly more successful.

Fascinating .

In 1976 when I lived in Guatemala City my brother in law took me to see “Guatemala’s First Car !” .

It was crude like this, I didn’t think they’d sell many as there was always a steady flow of used vehicles from the U.S.A. cheaply .

In Mexico VW Do Mexico made a crude pickup called the “Ormiga” (ant) ~ it was front wheel drive with a 1200CC 40 hp engine mounted backwards in the front .

A buddy of mine managed to find one it’s far rougher than this Cherito is .

-Nate

Interesting story, I hadn’t heard about the BTV before.

I do know that in the 70s Citroen had a similar project regarding a basic, crude small truck based on 2CV mechanics and aimed developing countries. It was called FAF, and that never took off either. According to Wikipedia, between 1977-81 a grand total of only 1786 cars were built across six different countries (Portugal, Guinea Bissau, Central African Republic, Senegal, Sri Lanka and Indonesia).