(first posted 2/8/2017) So we know the Czechoslovakian Tatras (a T603 is seen here in ’70s Bratislava), as well as those 411/412 VeeDubs with their awkward looks and poor performance, but what other big (over 1.6 litre) rear-engined four-door saloons did Europe produce? None? Well, close. Give or take a dozen…

The VW Typ 4 qualifies as a large RE saloon. Also, as a large RE failure.

In part 1 of this review of large mid- and rear-engined (RE) cars, the focus was mostly on the ‘30s and ‘40s, which was the heyday of the RE concept in general, except for sports and race cars – which are beyond the scope of this post. American engineers were very keen on the idea, but it had originated (or, more accurately, was re-discovered) in Europe in the ‘20s. Let’s explore these early attempts before we cast our eyes to the ’30s and the post-war period, when large RE prototypes were studied by several European automakers.

Rumpler

This is the granddaddy, the ur-Tatra, the first swing of the axle: the Rumpler Tropfenwagen (tear-drop car), built in Germany from 1921 to 1925 in about 100 units. If this car looks bizarre now, just imagine what it must have looked like then! The brainchild of Austrian aeronautics engineer Edmund Rumpler, the Tropfenwagen (or Tropfen-Auto) was available as a two-door sedan, a roadster and a LWB four-door limousine. It featured Rumpler’s patented rear swing axle, which was later widely used on most RE designs, as well as several front-engined cars, e.g. DAF, Mercedes-Benz or Triumph.

The Rumpler’s engine sat ahead of the rear wheels. It was a Siemens-built W6 with a displacement of 3.4 litres. The car’s aerodynamic body was way ahead of its time: when it was put in a wind tunnel in 1979, it was found to have a Cd of 0.28 – a figure that few (if any) cars of the ‘70s could claim.

It’s fair to say that the car was something of a failure in the marketplace. The only people who took a shine to it were taxis, as the body’s vast interior and high roof were an undeniable asset. Another use for the oddball vehicle was as a bit player in Fritz Lang’s 1927 sci-fi masterpiece, Metropolis, where several Rumplers were immortalized (and a few sacrificed) on celluloid.

Burney

English aristocrat Sir Charles Dennistoun Burney, a famous aeronautics engineer and inventor in his own right, elected to design a car that could include as many of his latest patents as possible. As a result, the Streamlines were not only unlike anything else on the road, they were all different one from the other. About 12 cars were made from 1927 to 1932, all with a similar layout: the engine was behind the rear wheels, allowing for a capacious cabin and entertaining handling.

The chassis was basically a FWD Alvis put back to front. The rear track was 13 in. (33 cm) narrower than the front, aiding the car’s aerodynamics. Most Burney Streamlines used a Beverley-Barnes OHC straight-8 mated to a Wilson pre-selector 4-speed gearbox, though the last three cars used a 185 ci (3-litre) Lycoming 6-cyl. instead (Burney was trying to market the car in the US at the time).

Famously, one of the Streamlines was bought by the Prince of Wales around 1930, finished in a suitably royal deep blue lacquer. But it wasn’t Burney’s intention to become an automaker as such: he was more interested in the patents and in licensing the Streamline to another concern.

Burney was successful in this endeavour: Crossley Motors bought the license and started marketing their version of the Streamline in 1934. The Crossley Streamline was a little different from the Burney cars: the radiator was moved to the front of the car (as was the battery), presumably to improve weight distribution. The wheelbase was shortened and the engine was now a 2-litre Crossley 6-cyl. unit producing 55 hp, mated to a Wilson pre-selector gearbox – which still propelled the car to 80 mph.

One of the two surviving Crossley Streamlines. Source: crossley-motors.co.uk

Crossley also replaced the Burneys’ airship-style fabric body with more traditional aluminum and steel panels. The price of the Crossley Streamline when it was launched was a hefty £750. By late 1935, that had come down to £395. It seems the 25 cars that Crossley put together were a tough sell. Either way, Crossley was to retire its automobile branch by 1937, earning the Streamline a coveted CC Deadly Sin nomination.

Škoda

It was perhaps unavoidable for the mighty Škoda works to design a Tatra lookalike. The result was not exactly graceful. The 1935 Škoda 935 Dynamic had a 2-litre water-cooled 55 hp flat-4 placed ahead of the rear wheels, just behind the rear seats. The 935 was a logical development of the firm’s previous RE prototype, the 1.5 litre Škoda 932 of 1932-34.

The car was put on display at the 1935 Prague Motor Show and never seen in public again. It was used and tested by Škoda through to 1939, when it was sold off to a lucky Czechoslovak citizen. Škoda tracked it down and bought it back in 1968, but only restored it to its full glory in 2015.

Dubonnet

André Dubonnet was the heir to a liquor magnate and used his considerable wealth to race Hispano-Suizas and Bugattis in the ‘20s. He helped develop and promote an innovative independent suspension system that was licensed to several manufacturers, including Fiat and GM. But he also dabbled in making full-blown prototypes.

Single front door opened on the front passenger’s side – 20 years before the Isetta!

The Dubonnet Dolphin was created in 1936. André Dubonnet was interested in making a truly aerodynamic car, which led him to opt for a mid-RE layout. The engine he picked, like a number of other prototypes at the time, was the 3.6 litre Ford V8, mated to a Cotal electromagnetic 4-speed transmission. Naturally, the Dolphin featured Dubonnet’s patented suspension on all four wheels. The three-door body was made by Hibbard & Darrin, one of the most expensive coachbuilders in Paris – but then, Dubonnet was a man of means.

Once finished, the Dolphin was taken to a circuit with its creator at the wheel, where it was raced against a standard Ford sedan with an identical engine. The production Ford reached 131 kph (82 mph) and required 15.6 litres / 100km (15 mpg); the fin-tailed Dubonnet’s top speed was 173 kph (108 mph) and used 10.7 litres / 100km (22 mpg). The car was then sent over to Detroit, where it failed to impress, and disappeared in the ‘50s.

Renault

Louis Renault presenting his new Juvaquatre compact car to Hitler and Goering at the 1939 Berlin Motor Show.

Work never stopped on the Ile Séguin, an island on the Seine just west of Paris covered entirely in Renault factory buildings, even during the darkest moments of the Second World War. Soon after the defeat of 1940, Louis Renault found a modus operandi with the Germans to allow his precious factories to continue operating. Developing new cars was strictly forbidden, but Louis Renault couldn’t care less: whatever happened, peace would come and new models would be needed. A secret prototype programme was initiated in late 1940, starting with a small RE car inspired by the KdF-Wagen that Renault had seen at the 1939 Berlin Motor Show. The car was continuously developed throughout the German occupation and finally emerged as the 4CV in 1946.

Renault “Projet 104 E” in 1943. These were tested until about 1946, but no production ensued.

Renault also planned to launch completely new 4- and 6-cyl. family cars after the war: traditional front-engined RWD affairs, with strongly American-influenced styling. In 1944, the French provisional government put Louis Renault in prison (where he died soon after in murky circumstances) and the company was nationalized in 1945. The new Renault executives, led by Pierre Lefaucheux, wanted to focus on the 4CV and the compact pre-war Juvaquatre for the time being.

It quickly became clear that a larger car should be added to Renault’s post-war range. Why let Citroën have all the 2-litre cars? Renault engineers therefore began work on a completely new prototype, “Projet 108.” The car was an upscale version of the little 4CV in many ways. Its 1997cc OHV 4-cyl. engine was placed behind the rear wheels, which eschewed the swing axles in favour of a novel trailing arms suspension.

One Renault 108 prototype fortunately survived. Tatra T600 kinship seems pretty blatant here.

The 108 was tinkered with and tested in 1948-49, but Renault engineers soon became disenchanted with the whole idea. The engine’s chronic overheating was impossible to cure. Another issue were the front wheel wells encroaching on the floor more than expected, negating one of the RE’s key features: ample legroom. Lefaucheux also reasoned that the 108’s unconventional architecture would make it a tough sell in a highly competitive market segment, and that its industrialization could be far more difficult than with a conventional RWD car.

By late 1949, the 108 was abandoned and a new 2-litre car with a front engine and RWD was slated instead, using a modified version of the RE car’s four-wheel independent suspension. Alas, the 1951 launch date was not moved, leading to the woefully underdeveloped Renault Frégate, whose lackluster career was to last until 1960.

Interestingly, Renault did not give up the large RE saloon idea and launched the “Projet 900” in 1958. This was a time when Renault worked in close collaboration with Ghia, who had a lot of influence in the 900’s styling. But the overall concept was pure Renault: a cab-forward RE car.

The underpinnings were closely related to the Dauphine and the Dauphine-based cab-forward “Projet 600” of 1957. However, the 900 aimed higher: it had a 1.7 litre V8 – essentially two Dauphine 4-cyl. blocks at a 90° angle – behind the rear wheels.

Second 900 prototype featured rectangular headlights and extra rear trunk, making the little V8 hard to get to.

The first prototype was built in late 1958 and immediately posed a problem: the lack of luggage space. Renault and Ghia modified their approach, placing the V8 ahead of the rear wheels and creating a serviceable trunk in the tail. The second prototype also had very different front and rear styling, with a hint of ’59 Chevy in the taillights.

A third proposal was devised with a fastback design, perhaps to address the jarring “coming-or-going” results of the previous two. These cars were serious attempts: they were tested on the track, where they fared relatively well due to their low weight (about 1000 kg) and decent aerodynamics. However, nearly all focus groups took an extreme dislike to the driving position, which was viewed as far too exposed and unsafe. The 900 was dumped in 1960 and Renault found itself without a large family saloon until the FWD Renault 16 debuted in 1965.

Selene I (above) had a spacious rear “salon” area and four doors. Selene II (below) was more of a 2+2.

For some reason, Ghia became besotted with the whole 900 concept and produced the 1959 Selene, penned by Tom Tjaarda, and the 1962 Selene II designed by Virgil Exner, Jr. Neither of the Selenes were fitted with engines.

Isotta Fraschini

One of the very last front-engined Isotta Fraschini 8B chassis, bodied by Touring in 1935.

Isotta Fraschini, founded in 1900, was a legendary Italian automaker in the ‘20s. Their 8-cyl. cars rivalled Duesenberg and Rolls-Royce in all aspects. The marque’s export-driven success fell on hard times after the 1929 crash though. IF was bought out by aircraft-maker Caproni in the early ‘30s, putting an end to chassis production. IF focused on trucks, aero engines and machine-guns until 1945, when Caproni found itself in need of new products. Aircraft were now out of the question, and there was a great deal of factory space to occupy.

Above: 1946 Luigi Rapi cutaway drawing; below: 1947 Zagato-bodied 8C Monterosa prototype with rear radiator.

Caproni had two or three concepts up its sleeve though. One was a 1.1 litre FWD car, which I’ve touched upon already. Another ambitious project was a RE executive car, to be marketed under the Isotta Fraschini marque. Work on this prototype had started in secret in 1943, under the aegis of Luigi Rapi.

The 8C Monterosa, as it became known, had a 3.4 litre water-cooled OHV all-aluminum V8 with hemi heads, designed by Aurelio Lampredi, that produced 125 hp (some sources say 110 hp) @ 4200 rpm mounted at the very rear of a sturdy box-section chassis. It also featured an all-synchromesh 4-speed gearbox plus overdrive, rubber-mounted suspension and built-in hydraulic jacks for all four wheels.

Above: Zagato’s 8C had a lot of Tatra genes; this was less true of subsequent cars. Below: either Zagato either reworked the first prototype, or built a similar body on a new chassis with a front radiator.

The initial prototype was clad with a sweeping limousine body, courtesy of Zagato, in late 1946. This initial prototype, resembling a fin-less Tatra T87, was extensively road-tested. The car was deemed a bit too tail-happy and that the V8 tended to overheat. To address this, the twin side-mounted radiators moved to the front of the car on subsequent chassis.

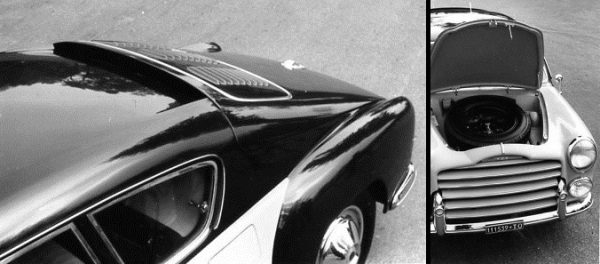

The Touring two- and four-door saloons were dispatched to various motor shows in 1947-48.

The second and third cars were bodied by Touring as two- and four-door saloons. The front-mounted radiator also helped with the car’s aesthetics, allowing the IF badge to be set within a big chromed frame more suited to the marque’s still-present mystique.

Caproni embarked on a PR campaign, sending the Touring-bodied cars to various motor shows and producing a lavish publicity brochure in several languages. This was done in spite of not having any chassis to sell!

IF only! Rapi’s 8C dream cars “for the autostrade, for the seaside, for racing, for wintertime,” etc.

The brochure is a true gem for this era. In it, Luigi Rapi let his imagination run wild, devising a dozen different bodies for the 8C Monterosa chassis – none of which were actually made, but the sheer creativity and style is breathtaking, like a fantasy RE garage.

This Boneschi-bodied 8C Monterosa convertible still exists, along with the Touring coupé.

The Isotta Fraschini was displayed again (and admired) at the 1948 Paris and London Motor Shows, this time with a two-door convertible body by Boneschi. The 8C Monterosa was doubtless one of the most refined European cars of its time, featuring a sophisticated heating and ventilation system, radio, a clock mounted on the steering wheel’s hub and seating for six.

The dashboard was as wild as the rest…

Unfortunately, Caproni did not possess sufficient political and financial backing to go push ahead with either the small FWD car, or the 8C Monterosa. Isotta Fraschini was still present at the March 1949 Geneva Motor Show, but after that date, the cars disappeared from public view. Caproni went into receivership soon after.

Brief, bizarre and bland: the T. Tjaarda-styled 1997 Isotta Fraschini T8, built by Fissore in four units.

The firm continued building IF-branded trucks, buses, trams and a variety of engines, but no passenger cars, until the aborted rebirth of the late ‘90s. Between three and six Isotta Fraschini 8C Monterosa chassis were made; two cars have survived.

One more of Rapi’s rapturous reveries for the road: this rakish coupé, which didn’t make it on the brochure.

Lancia

Full disclosure, folks: I’ve got virtually nothing on this. Lancia, it seems, tried their hand at a large RE car around 1947, going as far as building this prototype and getting Ghia to design a coupé body for it. This LP 01 (“Lancia Posteriore”) was powered by a 2-litre V8, had a tubular frame and a pre-selector gearbox.

Given the size of the engine and the history of the company, it is likely that a four-door would have been on the cars had this prototype been developed further. These seem to be the only photos out there of this mysterious LP 01, which was Gianni Lancia’s personal possession and seems to have disappeared.

NAMI

Original NAMI-013 mock-up, circa 1950.

Stalinist Russia isn’t the first place that comes to mind when wondering about interesting avant-garde automobiles, yet the NAMI 013 was undoubtedly one of the most advanced cars of its time. NAMI is the Russian acronym for the Central Scientific Research Automobile and Automotive Engines Institute, established in 1920. It led Soviet engineering in the fields of military vehicles, tractors, public transport, etc., even producing cars in the ‘20s and ‘30s. After the war, it produced many prototypes, with 013 being their first prototype car. The brains behind this project was Yuri Aaronovitch Dolmatovsky (1913-1999), who was involved in the design of the GAZ 20 Pobieda, the first post-war Soviet car.

Cutaway shows twin front radiators below the headlamps. Buick-style ventiports were the in thing, even in the USSR.

Dolmatovsky began work on NAMI-013 in 1949, using as many GAZ and ZIS parts as possible, but with a completely different philosophy. Hi goal was to maximize interior space, leading him to opt for a RE layout with a forward cab. The Pobieda’s 2.1 litre 4-cyl., which was mated to a NAMI-made automatic transmission, wasn’t very powerful, so Dolmatovsky tried to make the car’s unibody as aerodynamic as possible.

Compare & contrast: NAMI-013 and the Pobieda (above); other NAMI-013 and the GAZ 12 ZIM (below).

At least three roadworthy prototypes seem to have been made in 1952-53; Dolmatovsky drove one of them for the next 15 years. Somewhat shocked by the car’s appearance, NAMI directors pulled the plug on the project in 1953, although the basic idea would be recycled by Dolmatovsky (with much smaller engines) on other NAMI prototypes in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

Rootes

ERA prototype RE saloon for BMC, circa 1959.

In the late ‘50s, British company Engineering Research and Application (ERA, formerly English Racing Automobiles) were asked by BMC to build a prototype mid-range saloon. This car was to be compared with BMC’s in-house team efforts (led by Alec Issigonis) based on the Mini. ERA’s car, presented to BMC’s top brass in 1959, was a RE saloon with a 1.5 litre four – it was deemed inferior to BMC’s designs and soon discarded, just as ERA decided to refocus on other activities. But some of the ex-ERA engineers took the design to another company, Rootes, a couple of years later.

Rootes were working on the Hillman Imp, making them perhaps more receptive to the concept of a bigger RE car to replace their ageing Audax range. The project was codenamed “Swallow” and featured, much like the BMC prototype, a mid-RE design to allow for additional trunk space behind the rear wheels. Rootes initially planned to develop the car as both a 4-cyl. and a V8, though by the time the prototype was being built (in 1963), the V8 had been dropped in favour of existing Rootes engines, ranging from 1220cc to 1725cc. The styling was penned by Rex Fleming, who also did the Arrow saloon.

Surviving prototype shows its slim engine cover, which would have been real popular with mechanics.

But as the Imp encountered more and more problems, Rootes began to shy away from the Swallow concept. After all, a more traditional RWD car would present fewer potential teething troubles. So by 1964, the Arrow was given the green light and the Swallow was consigned to the historical footnote section. The Arrow was launched as the Hillman Minx and Hunter in 1966 and its descendants were built well into the 21st Century as the Paykan.

Porsche & Volkswagen

1960 Porsche prototype saloon by Ghia.

Porsche and VW were always umbilically tied as the creations of Ferdinand Porsche. But it was important for them to define their respective areas of competence, as Porsche’s activities always included consulting work for a number of automotive clients. The VW-Porsche understanding was that Porsche would never design anything that would be a direct competitor to the Beetle, except if the client was VW. This left a lot of potential for Porsche to develop its own cars, as well as cars for other automakers, such as Studebaker.

1962 Porsche saloon by Ghia. Below: the 1960 and 1962 cars either side of a Ghia VW EA 53 prototype.

Neither Porsche nor VW were making four-door cars in the ‘50s and early ‘60s, though this did not mean they hadn’t looked into the idea. Porsche commissioned Ghia to design a couple of four-door sedans based on the 356. It is possible that these cars were fitted with the 2-litre flat-4 that Porsche was developing for its 356 Carrera at the time.

1962 Tatra T603 A prototype (above) and 1966 T603 X (below) – a dash of Corvair, a pinch of Ghia?

The 1962 Ghia prototype is particularly interesting, as it shares some styling cues with Tatra prototypes of the ‘60s. Coincidence? Given the long and troubled history between VW/Porsche and Tatra, anything is possible…

VW 1500cc four-door prototype (above, circa 1960) was quickly ditched for the all-new 2-litre EA 128 design.

VW looked into a similar idea by the early ‘60s. The Corvair had given them food for thought, as did Porsche’s new 1991cc flat-6. The EA 128 Prototype (covered in more detail here) was made in 1963-65 with a de-tuned version of the Porsche 911 flat-6, as well as Porsche suspension front and back.

This interesting VW-Porsche prototype was developed as both a four-door notchback saloon and a wagon, but the idea was ultimately dropped in favour of the Typ 4 and its 1.7 litre VW flat-4.

Source: Road & Track

Finally, a fun custom-built special: the 1967 Porsche 911 S sedan made by coachbuilders Troutman and Barnes of Culver City, CA. The order came from Texan Porsche distributor William Dick, who wanted to give his wife a unique Christmas present. The 911 platform was lengthened by 21 in. (53 cm) to accommodate the suicide rear doors. The car’s interior was entirely trimmed in a specific type of leather that matched Mr Dick’s boots; the dash featured wood paneling.

Mr Dick’s bespoke Porsche was featured in many publications at the time, including the March 1968 edition of Road & Track. The car remained unique: though Porsche knew about it, it would be years until they dabbled in anything with four doors under their own marque – and by then, the notion of a RE sedan was beyond passé.

Epilogue

The saga of the large RE saloon came to an end in 1999 with the demise of the Tatra T700, which still had an air-cooled V8 in its tail – as had most of its predecessors since 1934. It was probably unavoidable: tougher EU emissions controls and Tatra’s lack of capital to design a new engine meant that the T700 never had much of a future. But what of the RE saloon concept? Is it dead and gone?

The answer in three words and one letter – no: Tesla Model S!

Having read this before, let me jump right in and thank you again for this superb history. I have of course long been a fan of RE cars, and many of these are familiar to me. But you’ve expanded my knowledge base significantly, especially with the 8C Monterosa. I’m utterly blown away and deeply fascinated, especially those magnificent color renderings of the proposed range of bodies. What an orgy or creativity.

The Nami was a mostly new one for me too. The fascination and appeal of the forward cab took a long time to subside, as also shown by the Renault 900/Selene. It just wasn’t going to fly, but it has such appeal to someone like me who likes to see things tuned upside down or back-to-front, every once in a while.

Years ago I remember reading an article on the Isotta Fraschini 8C (either Automobile Quarterly or an AACA publication) that mentioned an oddity about the car. The designer was a huge proponent of idiot lights and used them in reverse: If everything was OK, the light stayed lit. If the light went out, you had a problem.

I can imagine what that would have been like at night.

Your article brought back memories of a car I’d completely forgotten about over the past couple of decades. Thanks.

The cab forward look vehicles, to my eyes, look like a Ranchero/El Camino with the bed filled in, sort of like the 58 Chevy “business coupe” from yesterday, as well as being backwards. The reason for the idea not dying out can be due to the fact that in never being produced in any number, the style is wide open for a designer to interpret as they see fit. It has only seen the production line as a truck style or the Jeep FC.Knowing now that you as the driver are the designated crumple zone in case of impact, it makes it kind of scary to think of driving one.

Thanks Tatra. Good stuff.

Oh, now we’re talkin’! The Tatra T603 kind of fascinates me. This fabulous promo film is improved or sullied (depending on your taste) by this overdub job.

That Renault 108 prototype somehow looks remarkably similar to the early Saab cars.

I don’t understand why post-war designers persevered with trying to put the motor at the back.

They were huge fans of lift throttle oversteer 🙂

At the time it was the only way to get compact car with more room in the passenger compartment. Luckily Mini came about with it’s FWD transverse engine layout and solved that issue.

Fascinating read! The Renault large RE cars are completely new to me as were many others.

For completeness the Mercedes 170H may be deserving a paragraph.

All in all it took a lot of effort to realize the concept had too many disadvantages. I don’t think this concept will ever reappear.

The 170H is missing a couple of doors….

Rear engined cars were once quite common with several makes available here, Hillman with their Imp, Skoda MB and later models, Simca, Renault, and Hino and of course VW all regular sightings on NZ roads, VWs and locally Simcas are still to be seen but the rest have all faded from view.

Correct, and I really have a thing for them. However, the author was limiting the scope of the article to displacements of 1600cc or more.

To me the ones you have listed plus the FIAT Nuovo 500, 600 and 850, BMW 700 and NSU Prinz/1000/1200/TTS are all part of my childhood memories.

Great job! How do you manage to research your articles so well?

Wowee, more insane obscurities. I recently discovered my (new) favourite RE shape, though it is a two door.

I thought that red IF looked familiar. Rapi’s work for Fiat, coincidently originating as an eight cyl.

Now you’ve got me going. Goggling the Turbina led me to this Swedish effort.

http://blog.modernmechanix.com/swedish-dream-car/

Hot dog! A Swedish Dymaxion, I mean!

If that thing had one or two extra doors on it, I would have had to revise my post. It’s new to me…

That Fiat Turbina isn’t, but you’re very right about the kinship with that IF “dream coupe”. Makes it even sadder that none of L. Rapi’s 8Cs ever got made.

Just had a look at the Touring catalogue at the rear of ‘Il signor Touring: Carlo Felice Bianchi Anderloni (Automobilia, 2004). It cites 6 examples combined of the 2d/4d IF chassis being clothed by Touring. In the text at the front of the book, Anderloni mentions two chassis clothed by Zagato – an experimental road-going prototype and a promotional car shown at the 48 Mille Miglia which was then displayed at the Paris Show – and that “Zagato perhaps built a third one as well.” (p61)

Plus the Boneschi droptop suggests 9 or 10 examples all up, but I’m wondering if the 6 examples by Touring in their own listing might actually be the total number of IF chassis across the three carrozzerie. The catalogue doesn’t appear to make this sort of numerical mistake anywhere else, but the text preceding the listings only describes two Touring builds; one SWB 2d – originally metallic green, repainted black “… as it was not possible to build a new one because there was not enough time and Isotta Fraschini’s cash shortage.” (pp61-62), and one LWB 4d 8 seater as per your piece.

Rather reminiscent of a stretched BMW E30!

Why can’t today’s cars look as beautiful as the Isotta Fraschini ? I’m sick of these “modern” wedges . No one wants take a real chance anymore, and build something that truly stands out. One of the last distinctive American cars was the ’93 – ’97 New Yorker/LHS.

Wow. Well-researched doesn’t even begin to describe this. So many otherworldly designs…almost all of these were new to me. Fantastic article!

I wonder if that 4-door 911 still exists? Or the NAMI-013 that the engineer drove as his personal vehicle for so long?

This is an outstanding series of articles. To say that I’ve learned a phenomenal amount would be an understatement. Reading about these obscure rear-engine cars is like reading about deep sea creatures that seem almost too bizarre to be real. Thanks for taking the effort involved in writing these pieces!

The ERA prototype was mentioned as either being powered by 1.2 or 1.5 B-Series engines.

The Rootes Swallow prototype meanwhile was to be powered by 1250-1750cc all-alloy Coventry Climax engines derived from the 1220cc Coventry Climax FWE unit that powered the Lotus Elite, the 1390-1725cc Minx engines would have been too heavy for the Swallow along with the Avenger engines that did not appear until 1970.

As for the proposed V8 engine in the Rootes Swallow prototype though there is unfortunately no evidence to back up the following theory, there might be a connection between the Coventry Climax designed Swallow V8 and the 1.8-2.5 CFF/CFA V8 which Coventry Climax later designed for Jaguar to power its shelved XJ-Junior project that was to replace the Jaguar Mark 2 as well as challenge the Rover P6 and Triumph 2000/2500.

Especially since half a 2.5 Coventry Climax CFA V8 engine produces a 1250cc 4-cylinder (while a 1750cc 4-cylinder would in turn produce a 3.5 V8), with the 2.5 CFA V8 being capable of putting out 200+ hp from reading Walter Hassan’s book.

Interestingly the Imp’s grandaddy was actually a front-engined rwd prototype known as Little Jim. – http://anarchadia.blogspot.co.uk/2009/12/vintage-thing-no57-little-jim.html

Aaah ok — so that’s why I had read 1725cc !

I even wrote it down in the draft, but when I took some time to verify the Hillman engines, all I could find was the 1750cc. My bad. I’ll amend the text.

Thank you!

I think you’ve got it a bit backwards now, should be Cov Climax engines not Rootes.

From memory there was a removable panel behind the rear seat for engine service access.

Great article nonetheless, some fascinating stuff. I particularly like the Rumpler & Burney cars, which looking at them from today are almost a type of steampunk aero! The Isotta Fraschinis were too cool to live, well some at least.

Gosh – this is terrific material. Thanks for a great read on lots of new info!

Amazing. I can think of no other word for this excellent write up. Thank you!

Enter the Lamborghini Cheetah and LM001 off road prototypes.

Have any other cars featured a clock on the steering wheel hub?

Such clocks were optional on various Chrysler products in various markets in the mid-late ’50s to very early ’60s. One could even get such a clock as an accessory for the ’60 Valiant in certain parts of the world!

I think that my dad told me that they had an Oldsmobile with a clock on the steering wheel that used a self-winding watch mechanism at one point.

Amazing (again!) Thank you.

Excellent! Your article opened up a fourth dimension of automobile design. I just found my all-time favorite oddball car. Bring back the Dubonnet Dolphin and I’d name it the “Turbo Tadpole.” The design is so far out it makes the current Aptera car design look passe.

Just amazing, all over again. So much research…

I seem to recall reading in an old Briitish magazine that the Crossley Streamine used to boil at both ends. 🙂

Where would we draw the line between mid-engine and rear engine? The Skoda 935 seems mid-engined, I would have thought (but an amazing effort); and how to classify the final Tatras?

Could that be the same T603 i spotted in the Transport Museum in Bratislava back in 2019?

https://www.curbsideclassic.com/blog/museum/cc-travel-and-museum-classics-museum-dopravy-bratislava-slovakia/

Some of these “rides” look like “Roger Rabbit. toon cars”..lol I like that “60 Porsche saloon” iteration though.