(first posted 5/23/2017) OK; old British cars have a rep, but this one has been defying it for many years. I’ve seen it coming and going on the streets of Eugene since well before I started documenting the old heaps here. But I could never catch it; not so much because it was being driven particularly fast, but either I was on foot, or at a red light, or going the other way. But then one day at the place Stephanie calls my home away from home, there it was. I half expected to see some 2x4s strapped to its hardtop. Well, for a car with an engine that started out in a tractor, why not?

Why not indeed? When it comes right down to it, these old British sports cars are built more like trucks than what we might think of in terms of a modern sports car. In fact, the legendary Triumph four cylinder started life as a tractor engine. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, especially considering that tractor engine was quite modern for the times.

Here’s the Standard four in its original home: the Ferguson TE20 tractor. Yes, it looks just like the fabled Ford N tractor, but after the war, Ferguson and Ford went their separate ways, and Ferguson needed a suitable engine. Standard took on the task of building the TE20 at their Banner Lane plant, and developed a modern new OHV engine for it.

It had 1850 cc, was still a bit undersquare (longer stroke than bore), and used replaceable wet cylinder liners. In tractor tune, it made some 23.9 hp “at the belt”, @ 2200 rpm.

Ironically – or not – the Standard four was soon put to use in the Vanguard (CC here), and then the TR2 in 1953. That was of course the beginning of the line of TR sports cars, which rather caught MG off guard. The TR2 was quickly appreciated for its ability to handily outrun the weak-chested MGs yet cost only a very modest amount more. The Standard four, with two SU carbs, now made 90 hp. That was an impressive amount at a time when a new American Ford sedan still came with a 110 hp flathead V8. It could belt out a 0-60 run in 12 seconds flat, and hit 107 mph, numbers an MG (and most American cars) could only dream of. Who would have thought a tractor-engine Brit car would outrun a big American V8?

The TR4A is the ultimate evolution of the line still using the gnarly four. Now displacing 2.2 liters, it was rated at 105 hp. But it was very amenable to further hopping-up, and Judson supercharged versions readily exceeded 200 hp.

The TR4A may have looked essentially identical on the outside to the TR4, which preceded it for the years 1961 – 1965, but the “IRS” badge was the tip-off that things had changed under its Michelotti-styled exterior.

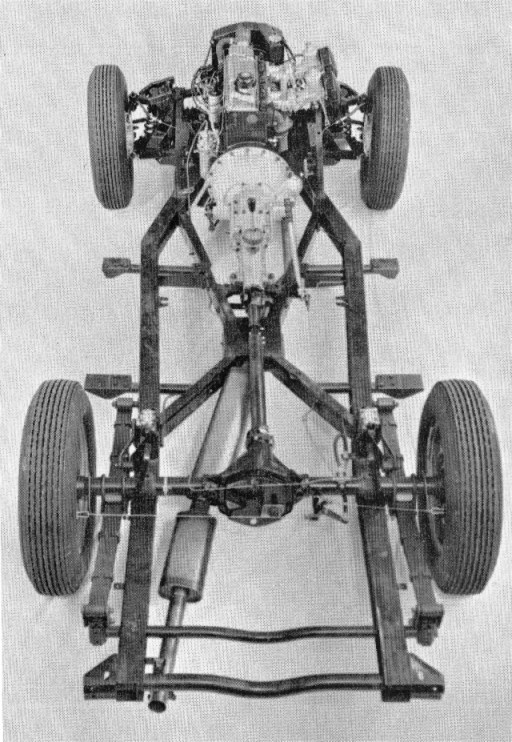

You got to hand it to Triumph: they were consistently more progressive and adventuresome than MG. One of the endless criticisms of the British roadster was its harsh ride, especially at the back end, which relied on relatively stiff leaf springs to locate the solid live axle. Here’s the TR4 chassis, which is very much in the old school.

I had always assumed that the TR4A’s IRS was just somehow cobbled up to fit the existing frame, but it turns out to be an all-new structure. (scans courtesy of stevemckelvie’s blog). Triumph was quite committed to IRS, although the swing axles that they used in the Herald (CC here) and Spitfire had significant shortcomings in terms of tuck-under at the limit. The TR’s rear suspension is a more sophisticated design, with double-jointed axle shafts and what appear to be semi-trailing arms to locate them.

The result was decidedly improved road-holding and comfort, and it was one of the key improvements that allowed the TR to evolve into its next incarnation, as the six cylinder TR5/TR250, and to the ultimate TR6, which was still able to provide a lot sporting pleasure without the punishing ride old-school Brit sports cars were being shunned for at the time.

The Triumphs were also know for being available with the optional Laycock de Normanville electrically operated overdrive, which could now be engaged on second and third as well as fourth, making seven closely spaced gear ratios to play with. That’s right up my alley.

The only thing missing from this slightly-battered but proud daily driver is a utility trailer. Then I’d be truly impressed. Or maybe he was just buying some wire to deal with the Lucas electrics?

Should we explain that “at the belt” meant at the belt pulley, a wide, flat wheel and standard feature on tractors up to about 1960 that allowed the tractor to serve as a stationary engine, driving a thresher, stationary baler, elevator, grinder, etc. by means of those long, flat belts you see in the pictures of old harvesters. Seems archaic, but actually quite efficient-the “belt h.p.” figure for these machines was usually higher than drawbar or p.t.o. And they were so cool-an old hand could get them really set up right so that the belt would rotate with hardly a vibration or bounce. Highly mesmerizing to a kid, and if you grew up around them you learned the value of belt dressing.

Yes; thanks for that addition. And good choice of word: mesmerizing. I saw lots of belt driven machinery as a kid, including an ancient saw mill some Amish guys set up in a woodlot, belt-driven by a veritable antique (and giant) gasoline tractor from the early days, the kind that looked like a steam-powered tractor.

The belt must have been fifty feet long, and had a 90 degree twist. I could not see why that belt didn’t just come right off the wheels, since there was nothing to restrain them. But they never did; or did they?

The pulleys for flat belts usually have a “crown” in the middle of their surface that keeps the belt from flying off sideways.

Good point. You still had to line them up exactly, and get just the right amount of tension, or they would work off. The twist, I am told, was to keep them from getting a resonant “bounce” going in them that could break the belt. It was always the “old timers” who would set up those long belts, by look and feel, even making allowances for the temperature and humidity, from years of practice. Like the old mechanic who insisted on setting distributor timing by ear.

The twist in the belt makes the belt, in effect, a Mobius strip-check it out if you haven’t heard of this before. One of M.C. Escher’s famous works depicts ants crawling on one, and they have some interesting mathematical properties.

Topologically, a Mobius strip is a shape with just one side-you can make one by taking a ribbon of paper, twisting one end 180 degrees relative to the other and attaching the ends.

In practical terms, a one-sided drive belt lasts longer than a two-sided belt because the entire surface of the belt is used.

It makes sense that thrifty farmers would have figured this out as a way to make their drive belts last longer.

Nice story a friend has a 1947 Ferguson it runs nicely and they are great tractors with their Fergusonsystem 3 point linkage. BTW the tractor pictured is not a very early one or has incorrect front wheels.

Not all TR4as were equipped with the IRS hence the IRS badge on cars so equipped. According to wikipedia only about 25% of the TR4a had the stick axle but none the less they did exist. Supposedly it was due to US dealers that were affraid that the increased in cost due to the IRS would have hurt sales too much so they talked Triumph to offer a lower priced live axle version which used a slightly modified IRS frame.

The shop I worked at while in college one “The” place to take your British car and the first time I saw a live axle TR4a I was quite shocked and figured someone must have hacked it in there but my boss said no they offered both. I don’t know how you would change the rear axle at least with the body on.

Supposedly it was due to US dealers that were afraid that the increased in cost due to the IRS

I would imagine US dealers were afraid of having to sell any car with the dread letters “IRS” on them. Who likes to be reminded of the taxman every time they want to go bomb around in their sporty little convertible?

Good point.

I had a toy one of these as a kid, one of the 1/18(?) scale stamped sheetmetal friction-drive cars. I always considered these quite handsome cars, although at the time, I considered them a bit more modern than an “old school” sports car like a TR-3 or a TD/TF.

I had no idea of the massive rear suspension re-do midway through the run. I had also never understood how much power these things put out relative to a typical sedan from the late 40s. Cool find, I’ll bet that driver has a lot of conversations with (older) strangers.

Ah, the effect of our toys on our young minds! Back when these were new, Airfix did a 1/32 scale plastic kit of one. 66 cents at the local newsagent. As a kid I was impressed by the look of the engine, and fascinated by the IRS detail – so different to any other model I’d built. That probably started me on a lifelong interest in the undersides of cars as well as the body shape.

And I was totally unaware that it was a whole new chassis – wow! Bet they had fun getting that past the finance department.

I once rode in a very built 1958 TR3A. It had been a racing car, but was restored as a high performance street car. It was pretty amazing as the engine seemed to have a lightened flywheel, and the tach swung to redline in a manner few cars can replicate. It had electric overdrive, and the driver, himself a racer of British sports cars, engaged and disengaged it at many times on our blast through the backroads of Stanardsville. I really wanted that car, but I thought it odd that the engine was redlined at about 5,250 rpm. Most OHV British sports cars have very high redlines after all these years of development. It turns out that the little tractor engine has some fundamental crank issues as revs go past 5,000 rpm. Not so much of an issue for supercharged applications, but a road block for the usual methods of improving power production with better breathing, bigger carburetors, and longer duration cams.

With the TR3, TR4, and TR5 with overdrive, you could use overdrive on second and third, as well as top, so you essentially had seven speeds if you wanted them. The rally drivers appreciated it because it minimized the “lugging in one gear, but droning away in the one below it” problem.

Funny to see a TR4 in Eugene with an IRL sticker and Donegal registration plates (ZP)

I wonder when that car left Ireland? And how it ended up on the left hand side of the USA?

And also how it ended up being a Left Hand Drive version in Right Hand Drive Ireland.

I suspect the car may have been purchased in the U.S., and the Irish plate simply bolted on at some point.

By a homesick Irishman.

The TR4A’s independent rear suspension was an adaptation of the semi-trailing arm system developed for the 2000 sedan. Triumph had wanted independent rear suspension for the TR4 pretty much since its development began, but Standard-Triumph ran into money problems following the end of their relationship with Ferguson, whose tractor business was bought out by Massey-Harris in the late ’50s. Standard-Triumph was acquired by Leyland, which did a good job of turning it around, but the rear suspension was shelved as too expensive.

The main difference between the TR4A/TR5 PI rear suspension and the 2000 (other than spring rates, naturally) is that the TR retained lever-action shocks in back because the sedan’s tubular shocks simply wouldn’t fit without major body changes. The big advantage of the semi-trailing arms was that the ride was a lot less abusive; handling was a mixed bag. One problem was the customary semi-trailing arm habit of kicking the tail out on an abruptly lifted throttle. (The sedans and the Stag had the same tendency, but with the sedan people weren’t as likely to force the issue.) The other was that Triumph used telescoping halfshafts to account for track changes under load and the splines would sometimes bind under power, particularly on the more powerful TR5PI.

The non-independent TR4A also used the new frame, which was cleverly adapted to take the live axle’s spring mounts. The reason independent suspension was optional for U.S. cars was that Genser-Forman, one of Standard-Triumph’s principal North American distributors, was very nervous that the added cost was going to hurt TR4 sales. Triumph had managed to keep the TR4’s advertised starting price just south of $3,000 and the independent rear suspension was going to upset that particular applecart. Essentially, Genser-Forman felt that the new suspension wouldn’t be seen as enough of an advantage to offset the price disadvantage.

The continued availability of the live axle may have been an advantage for people who ran their cars in SCCA events: The live axle setup was a bit lighter (something on the order of 50-60 lb) and on a racetrack, the live axle’s ride quality and reactions to knobbly pavement were really not issues.

Two other interesting points: One is that while the TR originally got the Vanguard ‘tractor’ four because it was expedient, by the time the TR4A came out, it was pretty much the only user except for a few Morgans and Triumph was eager to get rid of it. Second is that you didn’t mention its most novel feature, which was removable wet cylinder liners. One of the ramifications was that it was fairly easy to change from 1,991cc (TR3) to 2,088 cc (Standard) or 2,138 cc (TR4) by just swapping in cylinder liners of a different bore.

Umm; I did mention the wet liners. I remember JC Whitney having oversized liners and pistons, or at least to bring them up to TR 4 size.

Oops, well, clearly I missed that. Never mind…

I’ve also heard of the mixed effect IRS had on this car’s handling. The two issues (apparently) were a) it was less predictable when pushed, as you mention, and b) the IRS was softer, so the car bounded and pitched more over the road. The key improvement with IRS was said to be the ride, but I’ve never driven or ridden in one, so the standard large grain of salt applies.

I’m under the impression that Group 44 were the only major racers to run TR4s with IRS in competition in the US. Unfortunately, all of their TR4s were destroyed by 1971.

Vanguard sedans were built with the wet liner four into the sixties the Standard six became available on the phase three model but the four remained in production,

So if you got your TR4 stuck while flying down a country lane you could get a Ferguson with the same motor to pull you out? 😛

Good point…and naturally I have to wonder if someone, somewhere hopped up their Ferguson engine with Triumph hardware. Although 90+ horsepower in a light tractor sounds a bit scary…

Is it a reflection of does this car have a row of gauges under the steering wheel?

I’d say it looks like they added some gauges under the dash that you know actually work.

That’s got to make it hard to shift.

I had a black ’66 TR 4A IRS with white steel wheels in 1970. I was working at Falvey Auto, the MG, Austin-Healy, Jaguar, Rolls Royce dealer in suburban Detroit. I liked being the odd stand out employee who owns a Triumph at the odd stand out foreign car dealership in Detroit. I loved that car, especially a spontaneous all-night ride from Detroit to Madison, Wisconsin to see my girl friend at the time. I sold that car to move to Oregon. Sorry I sold it but not sorry I moved to Oregon. Maybe I could track that white one down and make an offer!

Interesting. I always took the old Ferguson tractor as a hurried-up knock-off of the Ford 9N/2N/8N series. Never worked one or seen one close-up. Little did I know, that while the Ford wheezed with its flathead, the Ferguson had a proto-Triumph engine. At 25hp, it would seem hardly stressed; especially since it was a modern OHV design.

Just a little tweaking and boring, and it generated 105 horses? Fascinating.

Same here-pretty ironic. The Ford had a flathead, I believe derived from the automotive flathead V-8, while the Ferguson had a tractor engine. The Ford Jubilee that followed had an ohv 4-cylinder (Red Tiger, I love the old names), derived from the Ford truck V-8. I wonder if there are other incidences of engines shared by cars and tractors- I know Continental supplied to both, but I don’t know of any similar overlap.

There were a few combines that used the SV (small V) that IH put in Scouts Pickups and Loadstars but as far as I know no tractors.

I still miss my TR4. It was dead nuts simple to work on and aside from major engine castings all parts were (and still are) available.

Nice find

Years ago, wasn’t it Dick O’Kane who wrote that “Sports cars are little trucks”?

OK Paul, that’s it for me. I read the article just knowing you couldn’t resist mentioning “Lucas electrics” but I thought you may just have done so.

But no, there it is, right in the last line. So near and yet so far.

Yes, yes, I GET it….all British cars were crap, all British cars had “electrical failure” written all over them. Blah bloody blah!

Frankly it is just BORING seeing it in EVERY post or at least one jackass mentioning it in the comments as though it is remotely interesting or new.

It is NOT….it is old hat….BOOOORING!

Oh, and by the way, between myself and all my family members we must have owned or operated well over 100 British cars of that era and I honestly can only remember one electrical problem. A 1956 MG Magnette repeatedly suffered wiper motor failures….until a tech who actually knew what he was doing fixed it then no more issues for the rest of the car’s very long life. (It was already about 8 years old and soldiered on until well into the 1970s).

So, in short, based on MY experience at least the “British electrics are crap” issue is way overblown. Now, I am NOT saying there are NO problems, of course not.

Just that it is one of those internet themes that grows and grows and develops out of all proportion of reality.

So, anyway, enough from me. I can’t read any more of that stuff so I’m gone.

Simon, I did it just for you, knowing that you’d respond exactly as you did (and have several times before). Boooooring! 🙂

Wow, this is hilarious…as touchy as Lu….oh never mind.

I owned a TR 4a – IRS back in 1980. I new of the Lucas electrical reputation back in the 70’s, long before the internet, so I don’t think the internet was that responsible, because I am no gearhead and knew it back when the internet was known only university and defense type people. I never had any problem with them, but I don’t mind the reputation one way or another.

Likewise. I don’t doubt there were problems, though. My extended family ran a lot of little Austins and Morrises back in the fifties and sixties. Plenty of mechanical and assembly-related gremlins, but the electrics didn’t seem to play up. Or maybe the Australian assembly plant knew of the home-market problems and specified higher quality.

Nar you got roughly the same cars and electrics we got they were horribly reliable if understood and maintained, I have a 1959 Lucas electrical system in my car port that works just fine and starts every time, Lucas distributors in Holdens were much preferable to the Bosch units and never gave trouble.

Interesting points, because my experience in Aus of family and friends in English products were a few very late 60’s and otherwise all 70’s stuff, and the electrics were indeed poor; cost pressures to suppliers under Leyland, perhaps? If it’s any comfort to our personally aggrieved commenter Simon (over THIS?!), I’ve always found my liking for French cars has meant enduring even worse electrics, right up to my current ride.

I think you’ve hit the nail on the head. Though I haven’t owned a British car, I’ve been around them a bit, and worked at an English car repair shop. The BL era seemed to be where things went downhill. Cost cutting, poor quality assembly by disgruntled workforce, you know the drill.

I’ve only owned two French cars: a Peugeot 404 and a Renault 12 wagon. I’m trying not to laugh, but yeah… both had some interesting electrical glitchery at times. Some components were unbelievably overbuilt (heater blower on Peugeot) and materials intensive (Ducellier fuses on Peugeot), or both (huge, spring loaded brass contacts to deliver power the defog grid, reverse and license plate lights on Renault’s tailgate). The Renault had a relay panel to the left of the steering column with about 9 relays, and they used just 3 or 4 pastel colors of wire throughout the whole thing. Pain to track individual wires down. Peugeot is too much to list. I still love the cars, though, and probably would put up with it again.

I recently replaced my daily ride with a later model of the same car the first one has been as reliable as the sun with no electronic glitches bar the Japanese Mitsubishi starter motor burning out a common problem Ive replaced two now and acquired another for a mates C4,

All the complicated computer systems worked as intended on my 408,000km C5 when I sold it the self leveling suspension did what its meant to the automatic lights and wipers worked, so, I bought a later model thats yet to need its first 160,000km cambelt change. it goes great.

The 4 cylinder wet liner engine was used in the second phase Triumph Renowns and the Roadster before the TR2 was launched.

I once owned a TR3A and have to say the engine was the most robust part of the car.

Back in the mid 70s I drove my TR from Jacksonville to my folks home in northeastern Pa. Made the trip (foolishly) with no special preparations, no spares of any kind, and no tools (and these cars had “unique” nut and bolt sizes). Over the course of the 1100 miles, done in less than 48 hours, 1 of the horns stopped working (no big deal) and about 60 miles from home the engine started to run rough. It wasn’t until I got home and had a chance to look under the hood that I discovered 1 of the spark plugs had “jumped out” of it’s socket. It hadn’t been very peppy those last 60 miles, but I had attributed most of that to steep hills and smallish mountains.

Yet, as robust as the engine was/is, TRs have their share of scuttle shake….as the British call it.

And I’m not sure I’d call Triumph “progressive and adventuresome”, as MG managed to build and sell (admittedly in small numbers) cars with twin cam engines AND 4 wheel disc brakes before 1960….did Triumph ever do that?

Don’t get me wrong, I am a BIG Triumph fan, having owned a Spitfire and a TR3. And I will kick myself for the rest of my life for passing up a Triumph Italia….ON TWO SEPARATE OCCASIONS. I am such an idiot.

Triumph did actually design a twin OHC engine for the TR, and made a very small quantity of them, which never went on sale. They were used in a potential new, high-end version of the TR, called the Triumph TRS, with a restyled body, of which just four cars were built (in fibreglass), and ran in the 1960 and 1961 Le Mans.

It wasn’t just a new head on the existing engine, it also had a new different block, so quite a major redesign. Googling ‘Triumph Sabrina engine’ will find you more, plus various theories as to why the car and the engine never progressed into production.

The cover for the cam drive had two prominent protrusions, which blessed the engine with its unofficial name – as per the Dagmar fenders, on Cadillacs – Sabrina was a very well endowed young English lady, who played minor roles in 1950’s TV shows and films !

The Standard Four was said to have been influenced by the Citroen Traction Avant engine (that later appeared in updated forms in the Citroen DS and Citroen CX), given it was planned for the pre-war Citroen Traction Avant to spawn a related V8 engine project that was even temporarily revived for the post-war Citroen DS, could Standard-Triumph have developed a related V8 engine project along similar lines?

Additionally there were plans to further enlarge the Standard Four to 2341cc to provide more torque for tractors and commercial vehicles as well as more power for the Triumph Renown (and presumably the Standard Four powered Triumph TR sportscars), along with a later proposal during the 1960s to produce a dry-liner version of the Standard Four engine allowing for further enlargement to 2446cc.

The 2446cc / 2.5-litre Standard Four prototype engine was even fitted to the Triumph TR4A yet compared to the Triumph 6-cylinder proved to be unacceptably unrefined, however such a large 4-cylinder engine might have been adequate enough had it been developed earlier during the early/mid-1950s before the Triumph 6-cylinder first appeared in the 1960 Standard Vanguard Six.

Going back to Citroen, their Traction Avant derived engine ended up remaining in production until 1991 at the latest via the Citroen CX producing a final maximum displacement of 2499cc as well as turbocharged and even diesel powered variants along the way.

Perhaps the Standard Four had similar untapped potential given what it was influenced by during development, though am more interested in its potential as a V8 engine thereby either butterflying away the Triumph V8 or allowing engineers time to iron out the Triumph V8 engine’s unreliability issues (until the latter at least becomes a precursor to the related SAAB V8 engine project). .

Standard fielded a flathead V8 engine pre WW2, Citroen TA engines predate the Standard four by ten years and Citroen had a prototype TA V8 running and driving in the 30s using a Ford engine,

Standard nevertheless drew influence from the Citroen TA engines amongst other things by its wet-liner construction as mentioned in Graham Robson’s Standard Motor Company book.

Was of the impression the Ford engine used in the TA V8 prototype was a placeholder until the actual engine was ready. The pre wet-liner Standard 4-cylinder of which was used to develop the flathead Standard V8 is intriguing in the sense Standard planned to convert the 4-cylinder to OHVs as Jaguar were already doing with its pre-XK6 Standard based 4/6-cylinder engines.

The unrealised prospect of a OHV conversion of the flathead Standard V8 together with a Riley Big Four derived V8, stand out as being the type of engines that might have been pretty-well received in North America in a post-war “export or die” context. Even though both engines likely had a limited-shelf life up to the mid-to-late 1950s at most and in Standard’s case no suitable car post-war.

Despite the differences in chronology, given the common influence both Citroen’s pre/post-war 4-cylinders and the Standard Wet-Liner make for interesting comparison (e.g. DS Sport Twin-Cam vs Sabrina prototype engines, similar scope for growth to 2.5-litres, etc), not to mention Land Rover’s engines that were developed from the Standard Wet-liner and encompassing the Santana 6-cylinder (plus 5-cylinder prototype) before evolving into the 300Tdi based yet much modified Brazilian 2.8-3.0 Power Stroke engines by MWM.

Even cooler than the fact you found an IRS version, it seems you found a rare Surrey Top, which anticipated Porsche’s Targa but was more substantial, with its (oddly) cast aluminum, fixed rear window frame and steel removable panel. Styling on all TR-4s was related to Michelotti’s work on the even-rarer (329 built) TR3-based Italia and also to the one-off Michelotti Corvette from 1956, esp. to his remodel of the chrome-slathered first version (link). Had this IRS in my TR6 but not the tractor engine. A sturdy piece, nonetheless…

Sorry to disappoint Simon but that reputation is well deserved. I worked for a BL dealer in the mid-70’s. Triumph and MG had just adopted the Lucas breakerless ingnition. The ignition module was integrated into the vacuum control unit. On the side of the distributor, right next to the engine. It was not a question of “if” but “when” it would fail and leave one stranded by the side of the road. We’d come in Monday morning to find the lot filled with cars that had died over the weekend. Eventually there was a recall that relocated a new module over on the fenderwell to solve the problem.

I also remember my Sunbeam Tiger has two 35 amp fuses. One for everything controlled by the ignition switch and the other for everything else. I then was exposed to VWs,SAABs and Volvos where the headlamps had separate left and right fuses as well as high/low beam fuses.

Had a ’67 TR4a IRS for awhile, these are fun to drive with more low-end power than the MGB, but much more antique feeling: tight ergonomics, shakey, rattle-y and loose feeling bodies, narrow track, the MG feels far more modern in most respects with their much stronger and more rigid monocoque body, and despite somewhat less power they had good low-end also and were as much fun or more to drive imo.

TEA18 was the first Standard engined Fergy tractor in 1947 not the TEA20 that wet liner four began its automotive career in the triumph Reknown not the Vanguard, and while some parts will interchange the engines in the cars are very different to those in tractors, People used to come to the Garage I worked summers in trying to get tax free engine parts for Fergies to revive their dead Vanguards, only to discover they dont fit, the blocks are entirely different as they are a structural member on the tractors

My dad had a 3a he bought new in 1959, we just sold his 62 TR4 a year ago. RE handling, either you can drive or you can’t with the car you are in. Too many folks far exceed their talent and ability. I’ve had everything from a TR2-8, all versions of Spitfires, GT6s, even a Stag. My first one I bought with my money was a TR4a IRS. I loved it. RE reliability, I covered over 112k miles from 2010-19 in my 78 Spitfire, including 1200 mile non stop drives to see my parents. I have always used my British cars for thousands of miles a year (44k since 2020 in my 73 GT6, including rain and snow) and have almost never been let down by an electrical issue.

With a little effort and regular use, you can rely on a Triumph as much as you can on a Toyota. The other cool thing is you can have them used as props for various things.